When you think of Disney, you may think of the storied, golden years of animation heralded by Walt himself; of today’s international media conglomerate acquiring Marvel, Star Wars, Pixar, and more; you may imagine the world’s leading theme parks with fairytale castles at their center, or pirates, princesses, and parades. One thing that you probably don’t associate with Disney? Failure.

When Disney’s California Adventure opened in 2001, it was meant to be the park that would thrust Disneyland into the 21st century, finally establishing Walt’s “original magic kingdom” as just one piece of a multi-day international resort destination. Instead, the park became one of the most infamous failures in Disney Parks’ history. Underbuilt, underfunded, and creatively-starved, California Adventure lacked the kinds of rides, characters, stories, and settings that Disneyland’s generations of local visitors had come to expect. And unlike the rare box office bust, this problem wouldn’t disappear with time…

Our deep, deep dive into Disney’s “California Misadventure” is a three-part exploration into the history of Disney’s biggest failure, its rise from the ashes, and its unusual undoing. In this entry – Part I – we’ll trace the park’s development and step into California Adventure as it appeared on its opening day to see exactly why fans, executives, and Imagineers agreed that it was broken at its core. Then, in Part II, we’ll walk through the park as it appeared after a grand, billion-dollar re-opening in 2012, and in Part III see why Disney may be making its most costly mistake all over again. Settle in…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

Disneyland Park

Before Disneyland, amusement parks in the United States really came in one of two forms. Some originated as Victorian-era “picnic parks,” supplied with patrons via the new railroad system, adding dance halls, carousels, and wooden roller coasters over decades and decades. Others took shape as open-to-the-public seaside boardwalks with gaudy, attention-grabbing games, food stands, and thrill ride admissions bought a la carte.

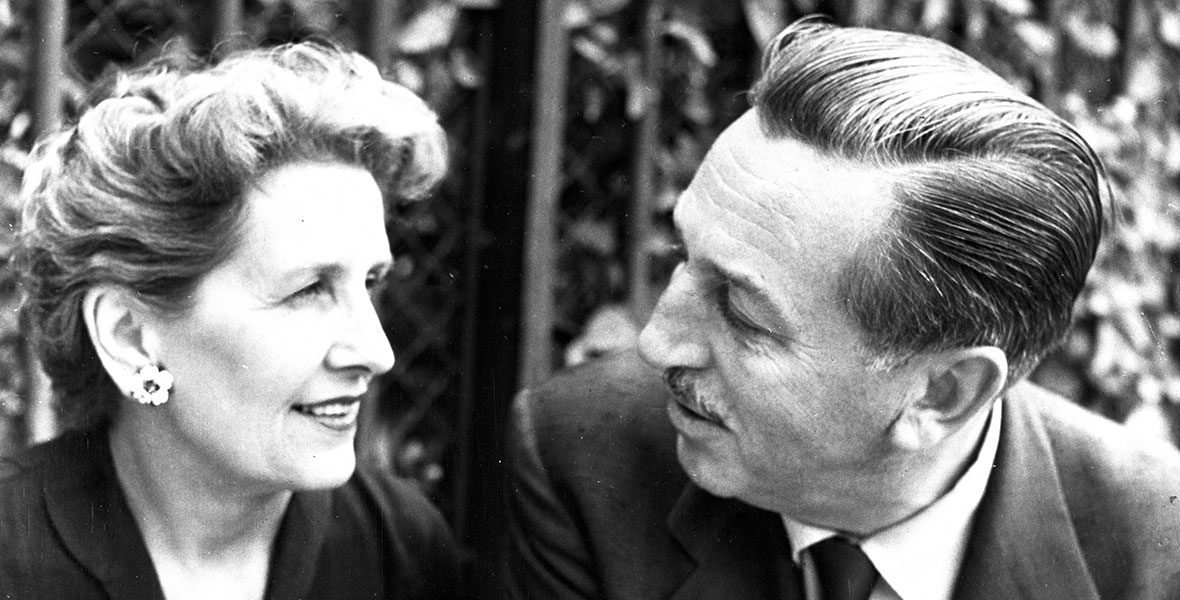

Given that those were the prevailing images of such amusement parks, it’s no surprise that when Walt showed interest in opening his own, his wife Lillian asked, “Why would you want to get involved with an amusement park? They’re so dirty and not fun at all for grownups.”

“Well, that’s exactly my point,” Walt is said to have told her. “Mine isn’t going to be that way. Mine’s going to be a place that’s clean, where the whole family can do things together.”

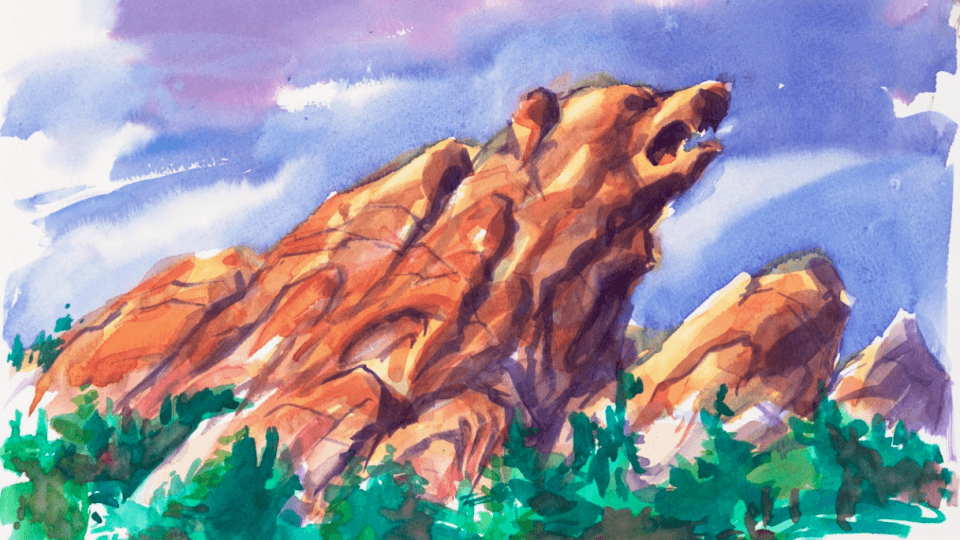

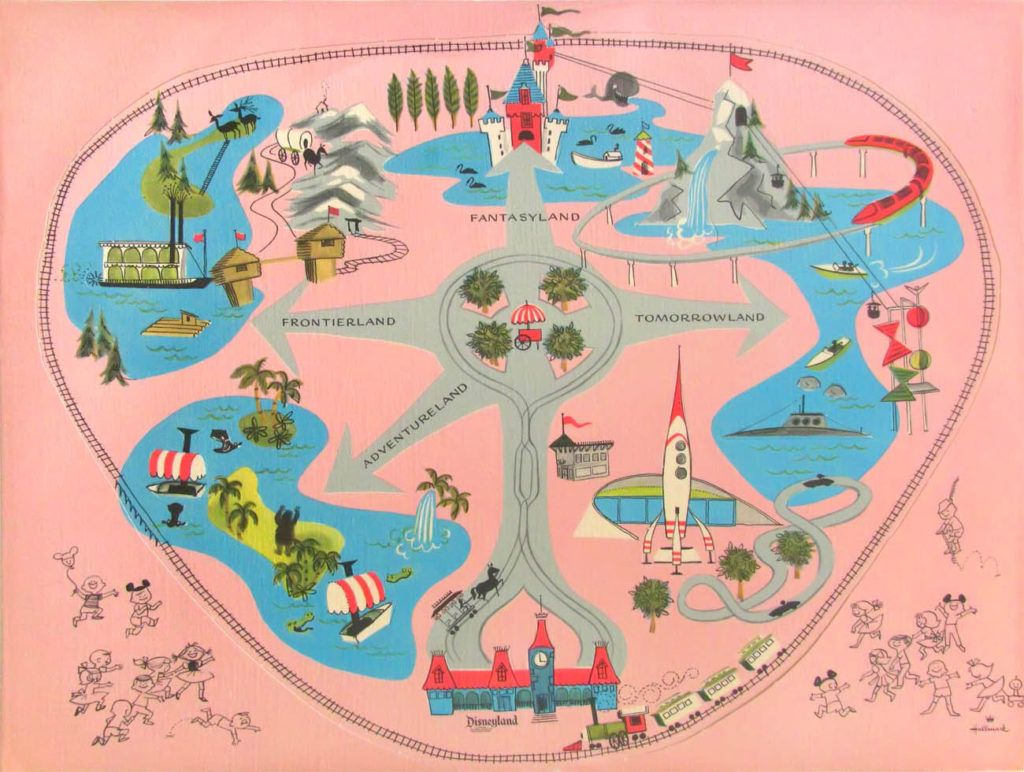

And when the first guests to Disneyland stepped through the gates of Walt Disney’s new attraction in 1955, they would find that it was indeed entirely unlike anything that had ever come before. Walt Disney’s park had it all: misty African jungles, turn-of-the-century town squares, cities of tomorrow, storybook villages, even the Old West as seen in mid-century America’s shared daydreams, brought to life not by carnies, but by filmmakers and animators.

Sure, Disneyland in the early years was rough-hewn and occasionally even sparse. But it contained within it the foundational DNA of something astounding. We know that once it matured, Disneyland’s true “magic” became apparent: that the park transported guests to idealized, romanticized times and places; to the “worlds of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy” passed through a lens of nostalgia and cinema; places not found on a map, but born of pop culture’s collective vision of the past, the future, and the adventure, frontier, and fantasy that exists in between.

If there was one thing Disneyland did not have, it was size. Walt’s original land purchase totaled about 160 acres, of which 60 was occupied by the park itself. The rest was divided between the massive parking lot – with an eventual footprint larger than the park! – and the various “backstage” facilities powering the property.

Otherwise, the entire complex was landlocked by streets to the west, south, and east, and the soon-to-be-Interstate 5 to the north. Situated cozily on what amounts to a few square city blocks, Disneyland was snuggly cemented in place with little room for growth.

That might’ve been fine… except that once Disneyland opened, the orange groves around the property were gobbled up as hotels, motels, convenience stores, and more squeezed into every square foot between West St., Harbor Blvd. and Katella Ave., desperate to get a foothold near the young park. Of course, each built its sign taller, brighter, and louder than the rest as the sleepy farmland of Anaheim became a bustling urban landscape.

It’s no secret or surprise to fans of Disney Parks that Walt detested the encroaching battle lines of reality. And for first-time visitors, it can be astounding that, from the Disneyland Railroad, you can hear the commotion of cars; guests staying at off-property hotels can be a 5 minute walk from the parks; and the Monorail provides astounding aerial views of traffic jams on Harbor Blvd.

While the ingenious earthen berm built around the park acted as a great wall to keep visual and auditory intrusions out, the fact remained that the real world was a little too close to Disneyland for Walt’s liking.It was Disneyland’s tiny footprint, of course, that inspired Walt to do things differently in his second take…

The Florida Project

Dissatisfied by the rapid urbanization of Anaheim and the way that the modern world so invaded Disneyland’s sphere, Walt and his team did something unusual: they began scouting for a space to build something different. But this time, Walt was determined to control the experience on a much larger scale. Of course, we know now that the Walt Disney Company was able to purchase massive landholdings in sleepy Central Florida (this time under false company names so as not to attract the attention of developers, who might otherwise rush in to buy parcels themselves) and even work to establish the Reedy Creek Development District, a strange (and questionably legal) political arrangement whereby the Walt Disney Company effectively governs itself and grants its own permits.

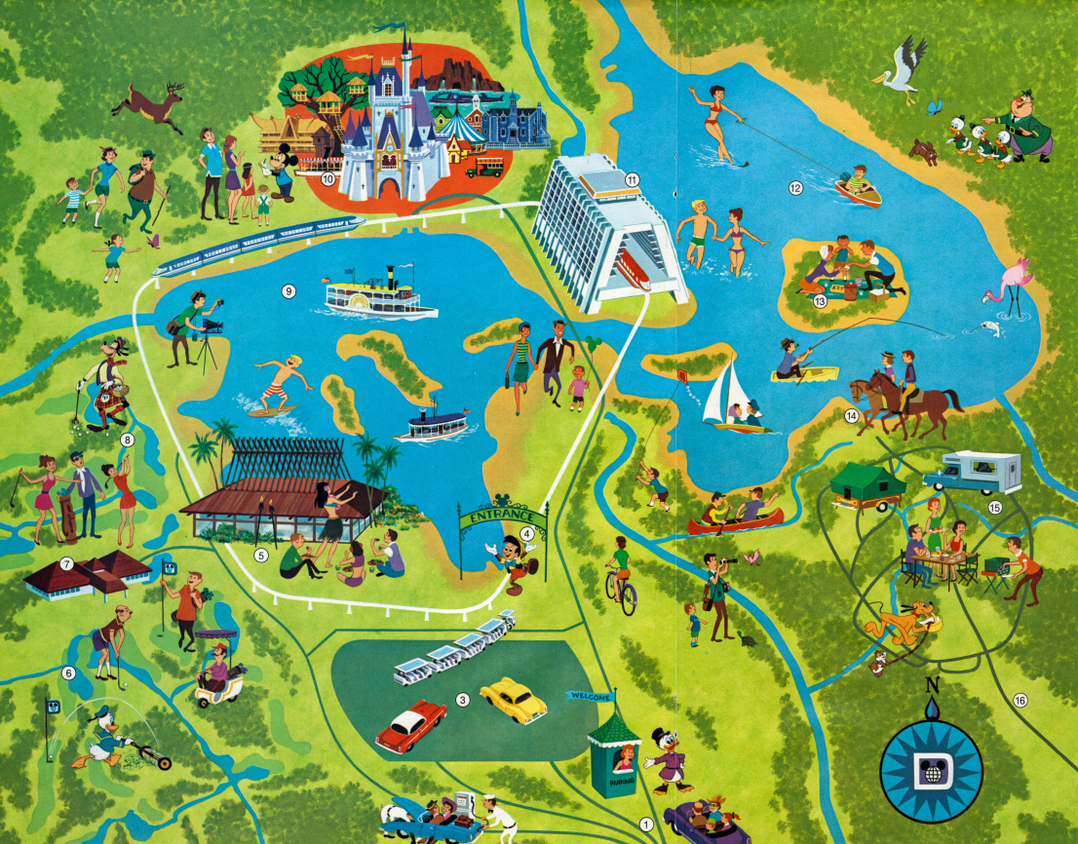

Walt Disney famously said of his then-unnamed Florida Project: “Here in Florida, we have something special we never enjoyed at Disneyland… the blessing of size. There’s enough land here to hold all the ideas and plans we can possibly imagine.” And it did. In Florida, Walt Disney Productions had well over 25,000 acres of undeveloped land, spanning about 40 square miles (famously, the size of San Francisco, or twice as large as Manhattan).

Walt’s initial dreams of an Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow died along with him in 1966, with the renamed Walt Disney World pivoting instead to become “The Vacation Kingdom of the World” – an international getaway born of the rise of commercial air travel and anchored by a super-sized Disneyland – 1971’s Magic Kingdom.

And as Walt had predicted, unlimited land and the benefit of foresight and master planning allowed Magic Kingdom to build higher capacity attractions, to replace Disneyland’s narrow pathways with wide open plazas, and to build its infrastructure with an anticipation of international success that Disneyland simply hadn’t accounted for – larger restrooms, larger restaurants, transportation systems, and more.

And it only got bigger from there. When then-new CEO Michael Eisner arrived at Walt Disney Productions in 1984, Walt Disney World was entering its teenage years. And like a good parent to any teenager, Eisner was determined to use his influence to shape the rest of the Florida resort’s life for the better, positioning it for adulthood.

Through the late ’80s and early ’90s, Walt Disney World evolved in a manner few could’ve envisioned. A global entertainment destination, the resort would soon play host to four theme parks, three water parks, a “downtown” shopping and dining district, vacation timeshares, an educational institute, and literally dozens of resort hotels – altogether creating in Walt Disney World an international destination that could command multi-week stays from global audiences. Walt Disney World was a financial and cultural behemoth…

… And then there was Disneyland.

Growing

By the early 1990s – just as Walt Disney World was gearing up for its fourth theme park – Disneyland looked… well… quite a bit like it had in 1955: a single theme park, its gargantuan parking lot, and across West St., the lone Disneyland Hotel.

Spurred by still-fresh CEO Michael Eisner, The Walt Disney Company planned to change that. Early on in his tenure, Eisner began to impress upon his team that Disneyland needed to change. If Walt Disney World could command stays between four and ten days, it was nothing short of a waste that Disneyland – even four decades after its opening – remained a single-day park catering almost entirely to regional audiences.

By far, most of Disneyland’s visitors came from within a hundred miles of the Southern California park. Those who were from outside the region often visited for only a day, treating Disneyland as you would a respectable and historic sideshow – a single stop on a larger road trip through the Golden State. Come hell or high water, Eisner and his team agreed that Disneyland could, should, and would grow into a multi-day, international resort destination, just like Walt Disney World. The only question was how to get it done.

On May 8, 1991, the company officially announced plans for an unprecedented expansion that would take the meager Disneyland theme park and position it as just one piece of the much larger Disneyland Resort.

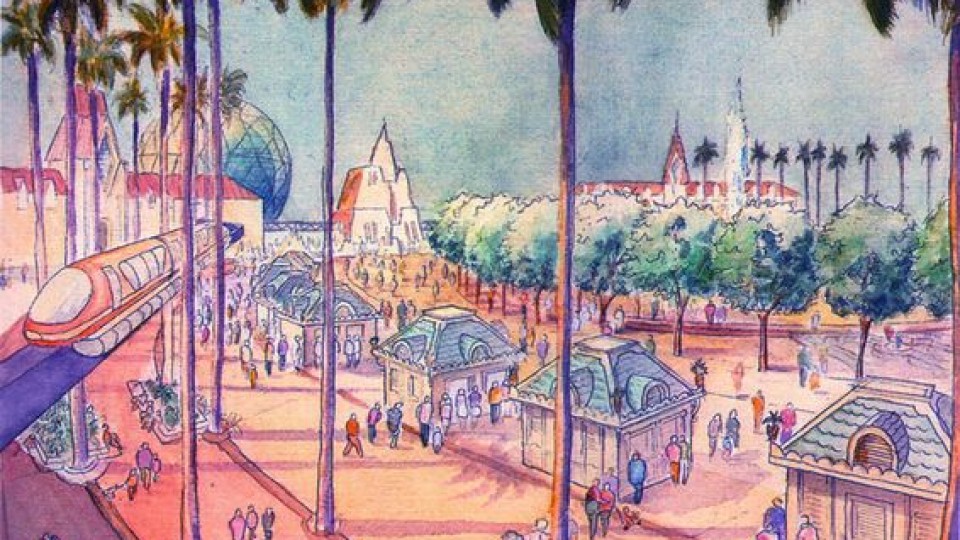

For an estimated $3 billion, nearly every square foot of Disney’s Anaheim property beyond Disneyland’s berm would’ve been transformed. The planned expansion would’ve included a hotel district equipped with no less than four completely new resort hotels; a shopping district built around a six-acre lake; a 5,000 seat amphitheater that could host internal and external concerts, and gargantuan new satellite parking structures from which continuously-loading PeopleMovers would effortlessly draw arriving guests, depositing them in a new central Disneyland Plaza.

There, with the familiar wrought iron gates of Disneyland and the historic Main Street Train Station behind them, guests would find themselves facing something very new. Where once the blacktop expanse of Disneyland’s parking lot had been, an entirely new theme park would appear…