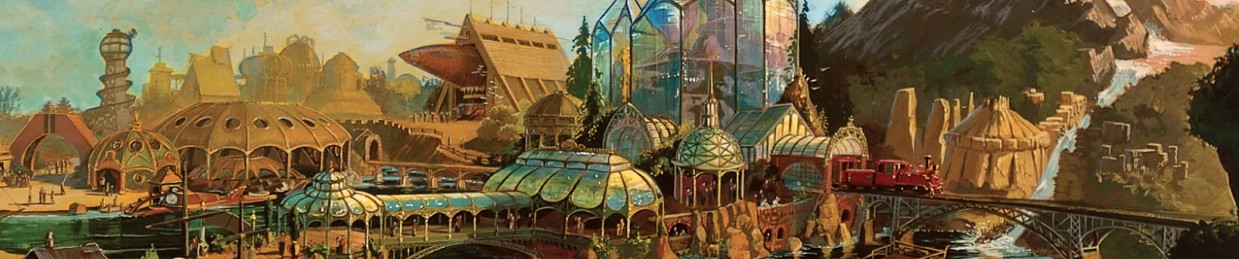

Long ago and a world away, great adventures await… In the pantheon of beloved cancelled concepts at Disney Parks, there’s perhaps no project as legendary as that of Discovery Bay. Once envisioned as a continuation of the story of the Rivers of America, this retro-futuristic steampunk land of time machines, submarines, lighthouses, greenhouses, inventors, and adventurers was set to become an icon of Imagineering… but it was never built.

Luckily for us, anything’s possible in Possibilityland, our ever-expanding alternate reality walkthroughs of never-built attractions from around the globe. So even if Discovery Bay never saw the light of day, today we’ll trace the true history of the concept straight from page one and explore the could-be classic attractions this land might’ve contained… Then, we’ll see not only why this city by the bay was scrapped, but where its DNA lives on…

Of course, to understand the story of Disneyland’s unbuilt mechanical Mecca and steampunk San Francisco, we have to start with the real story and a cross-continental journey to coast…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

Westward story

In 1803, the United States – barely three decades old – purchased 828,000 square miles of land claimed by the French as part of the Louisiana Purchase for $15 million. That year, President Thomas Jefferson dispatched the Corps of Discovery Expedition (lead by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark) to map America’s new land and to find “the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent” while declaring sovereignty over any Indigenous peoples encountered along the way.

By the 1830s, fur traders and trappers had successfully laid the beginnings of the Oregon Trail, the 2,000 mile emigrant route connecting the Missouri River through modern day Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Idaho to the verdant valleys of the Oregon Country on the West Coast. Initially accessible only by foot or by horse, it’s estimated that over 400,000 people took the 2,000 mile Oregon Trail in search of the wonders of the West, gradually growing the route with bridges, roads, and ferries to make the perilous journey faster and safer, accessible at last to covered wagons.

Expansionism had been set. By the mid-1800s, the concept of “manifest destiny” had laid out a path for the country: that Americans were called – no, destined – to expand West, claiming the continent from coast-to-coast and taming any threats – natural or cultural – that dare stand in their way. Life was hard for the farmers, miners, ranchers, and business owners and their families who chose to follow expanding wagon routes into the wilderness… but the call of opportunity and the offer of homestead was too much to ignore.

And for much of the 1800s, that call was only amplified by the possibility and the promise of gold.

“Eureka!“

On January 24, 1848, gold was found in Sutter’s Mill, Coloma, California and seemingly overnight, American culture changed forever. Historian H. W. Brands described:

The old American Dream was the dream of the Puritans, of Benjamin Franklin’s “Poor Richard,” of men and women content to accumulate their modest fortunes a little at a time, year by year by year. The new dream was the dream of instant wealth, won in a twinkling by audacity and good luck. This Golden Dream … became a prominent part of the American psyche only after Sutter’s Mill.

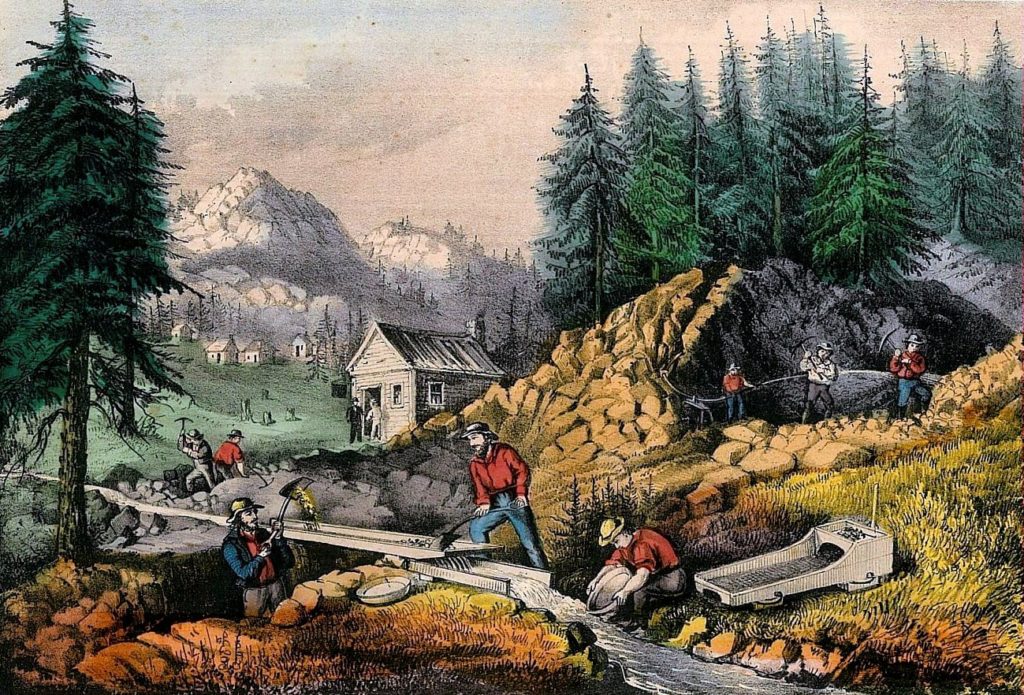

It’s believed that 300,000 people descended on the boundless Californian territory (won from the Spanish just two years earlier) in the years following the 1848 discovery. Half arrived via the wagon routes and California Trail emblazoned across the country.

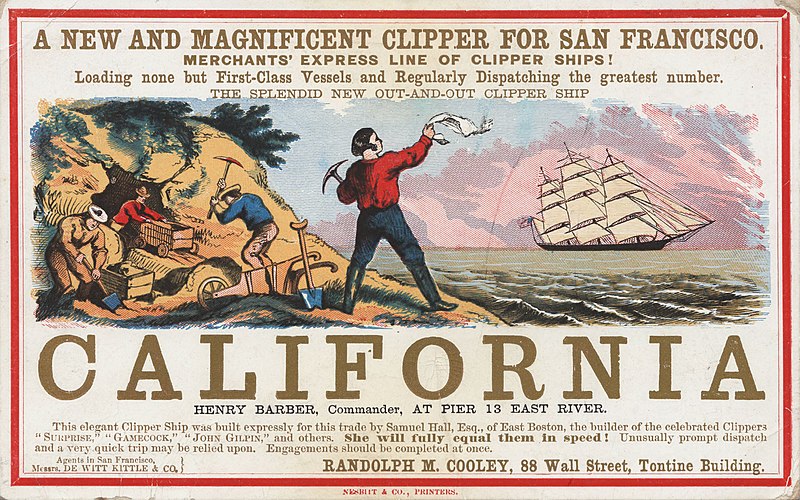

The other half arrived by sea. Tens of thousands of migrants from New York, Boston, Latin America, Europe, Australia, and China made their way toward the promise of wealth, prosperity, and wonder in California. Their waypoint? San Francisco, the “Golden Gateway” to the West.

San Francisco grew from a small settlement of about 200 residents in 1846 to a boomtown of over 36,000 within six years. Its harbor couldn’t expand fast enough to dock all of the sailing ships arriving on its coast, described as a “forest of masts” on the shore, necessitating the construction of enormous wharves that the city is now known for.

In fact, arriving explorers from New York, China, and Europe were often known to simply abandon their ships, racing inland to the gold fields. Eventually, those ships were reclaimed as saloons and hotels for the rapidly-expanding San Francisco.

In 1850, fast-tracked statehood for the impossibly-expanding California was granted. It’s fitting that “The Golden State” was fueled by a golden dream that had drawn prospectors, writers, architects, explorers, and sailors from around the globe to the seaside port city of San Francisco. Over the course of the California Gold Rush, the modern equivalent of tens of billions of dollars worth of gold had been unearthed, making California and the growing Bay Area a center of global trade.

By most accounts, the 1848 California Gold Rush came to an end in 1855. The Golden Dream had relocated. The latter half of the 19th century shifted to the American Southwest, where the American frontier took on its most iconic form: clapboard desert towns of saloons, red rock buttes, company stores, and gold mines accessible by the Westward-expanding railroad.

And though we’re skipping forward a century, that’s where our story picks up.

Pop-Cultureland

When Disneyland opened in 1955, Frontierland was among the park’s opening day lineup. Though nearly a hundred years had passed since the era of the Old West, it was more relevant to Americans than ever. That’s because in mid-20th-century America, tales of the wild frontier and the rugged explorers who’d conquered the Old West were at the height of pop culture.

In the 1950s, Western films lit up the silver screen making John Wayne and Charlton Heston household names; The Lone Ranger was the era’s Iron Man; kids spent their summer days outside playing “Cowboys & Indians,” stopping only to watch Howdy Doody, while families gathered for Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and Disney’s own Davy Crockett.

Yes, in Walt’s time, “frontier” was worthy of a spot in Disneyland, elevated to and revered alongside “adventure,” “fantasy,” and “future.”

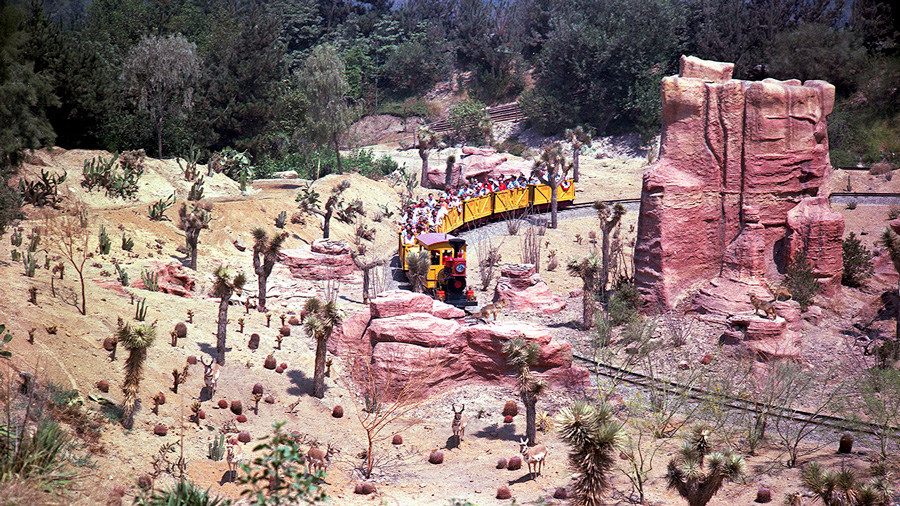

Frontierland let guests step into the Wild West they’d dreamed of; to dine in raucous saloons; to buy coonskin caps and pop guns; to explore on Tom Sawyer Island; to take on the Living Desert by pack mule, stagecoach, Conestoga wagon, train, and, later…

… the Lost Legend: Mine Train Through Nature’s Wonderland, chugging through desert buttes and past Jungle Cruise-esque wildlife that awaited on the remote frontier.

The problem is, the era of the Western didn’t last. By the 1970s, the pop culture gold rush had ended, and Frontierland was looking like a dusty, barren remnant of a long-gone moment in time… It was time for an upgrade.