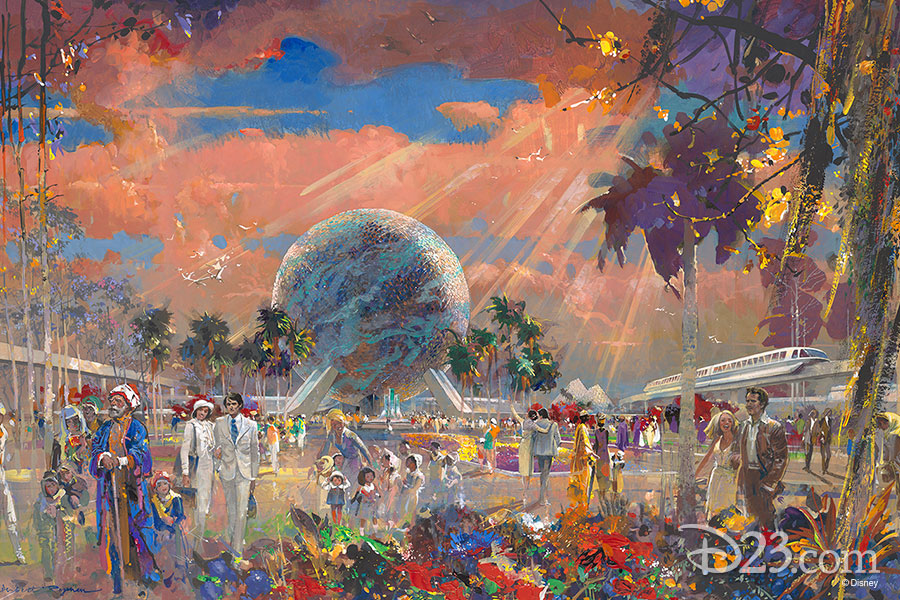

When EPCOT Center opened on October 1, 1982, it was a sincere display of futurism, innovation, corporate power, and industry. Because in hindsight it also has an inordinate amount of closed classics, you’ve heard us examine the park’s ambitious and brave concept in Lost Legends features telling the in-depth stories of Journey into Imagination, Horizons, Maelstrom, Soarin’, and Body Wars – just a small sampling of the stunning features preserved in our Lost Legends collection.

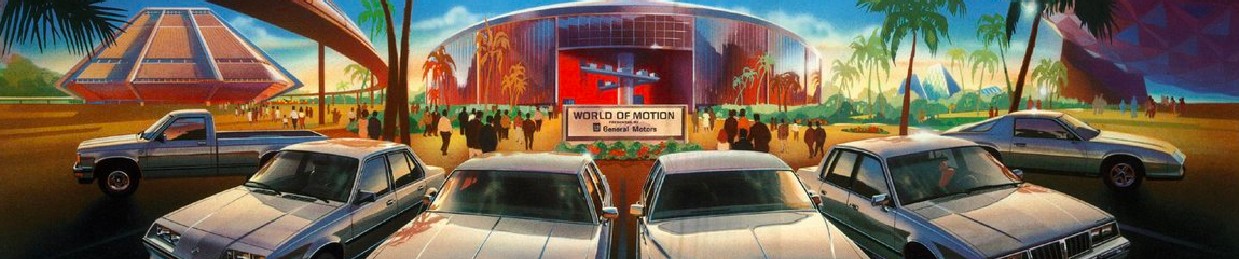

But there is perhaps no Lost Legend more aligned to the park’s grand, educational, World’s Fair roots; more a memorial to Walt Disney’s own fascinations; more in tune with EPCOT Center’s celebration of human innovation than World of Motion.

Often overlooked in Epcot’s history of bulldozed classics, this incredible, epically sized dark ride through the history of transportation was no less impressive or important than Universe of Energy or Spaceship Earth. In fact, its story is of a one-of-a-kind, whimsical, and wondrous Disney dark ride created by famed animators packed with as many creative gags and effects as the Haunted Mansion.

So today, in History in Motion: Part I, we’ll begin with the proverbial invention of the wheel and examine the truly unique experience of this EPCOT Center original. Then, History in Motion: Part II will take us on the road to the ride that replaced it; the pedal-to-the-metal making of the original Test Track… Buckle up!

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

The Road to Tomorrow

Walt Disney’s fascination with transportation was no secret. When Disneyland opened in 1955, its Tomorrowland contained the Autopia – an honest-to-goodess showcase of future modes of transportation given that President Eisenhower wouldn’t sign the Federal-Aid Highway Act until nearly a full year. later.

The opportunity to drive along multi-lane highways was a model of what would be, and Walt’s “automobile utopia” was a glimpse into a car-centric future – still emerging post-World War II. It was joined by the Junior Autopia in 1956 and the Midget Autopia in 1957, with the former expanding into the Fantasyland Autopia in 1959.

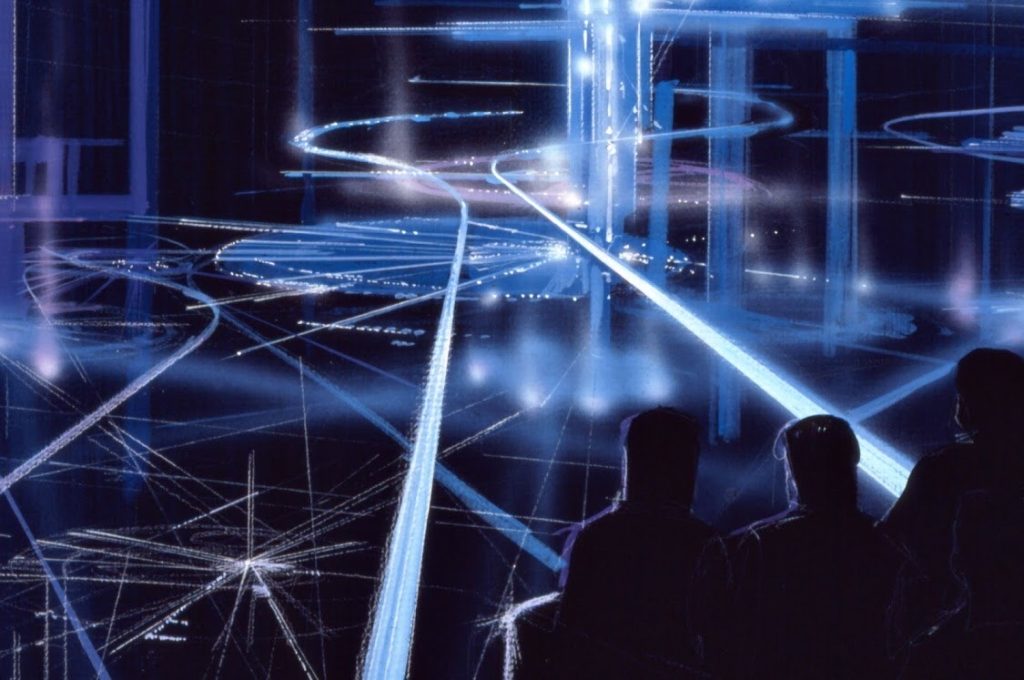

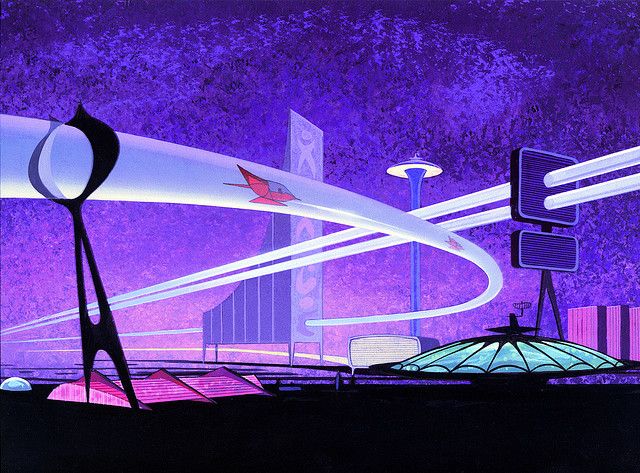

Three years after Disneyland opened, on May 14, 1958, the Disneyland television series hosted by Walt featured an episode called “Magic Highway U.S.A.” Tracing the history of the automobile and the highway system, “Magic Highway U.S.A.” envisioned fantastical new modes of transportation, noting that, “such visionary ideas which today seem sheer fantasy will be commonplace to future generations.”

Among its optimistic ideas for the future of automobile transportation, werecolor-coded highway lanes using radiant heat to protect from ice, rain, or snow. Even fog might be eliminated by dispelling devices along the future’s roadways. (The futuristic expectations animated in this TV special were even re-used forty years later as the pre-show for Disneyland’s Declassified Disaster: The Rocket Rods – a “transportation system of tomorrow” that didn’t work.)

At least one innovation imagined in “Magic Highways” had come through in the last half-century: video screens replacing (or at least, augmenting) rear-view mirrors. Put another way, “Magic Highway, U.S.A.” probably best falls into the category of mid-century speculative fiction. But even so, Walt Disney was determined to keep moving down the road to tomorrow, and after Disneyland opened, most of his next projects dealt with transportation.

Fundamentals

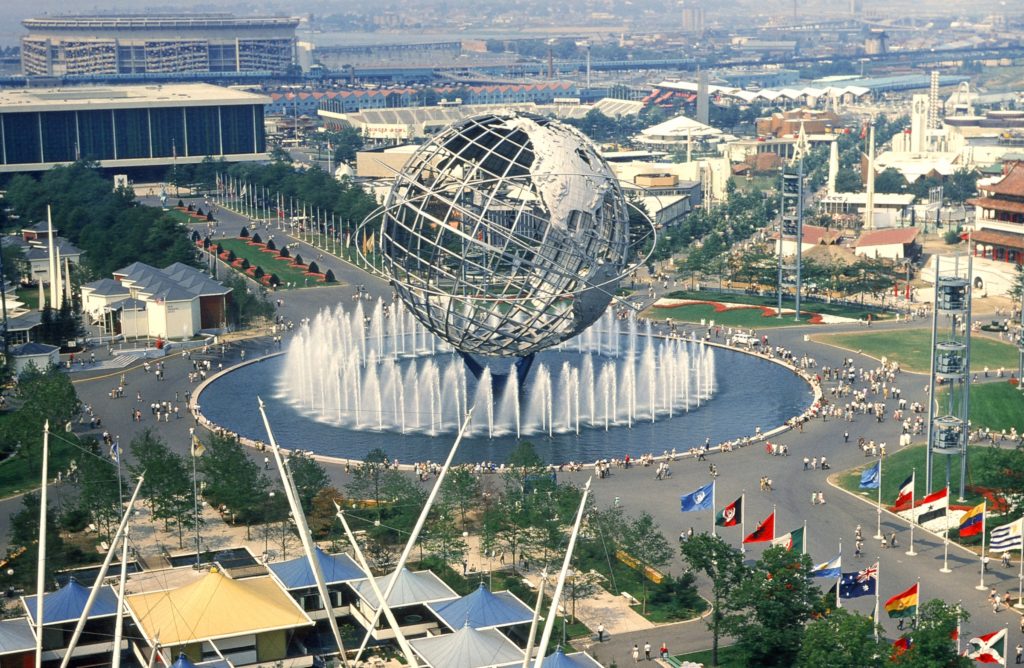

For example, consider Disney’s role at the 1964 – 65 New York World’s Fair through a new lens. Though they’d been around since the 1800s, by the mid-century these global expos hosted in international cities had become corporate showcases of innovation and industry. At the height of the 1960s (with all its Americana, optimism, and futurism in tact), people flocked to Flushing Meadows in Queens to see what wonders General Motors, IBM, Bell System, Sinclair Oil, and Chunky Candy would have to put on display.

Three of the attractions WED Enterprises created – “it’s a small world,” Carousel of Progress, and the Ford Magic Skyway – were essentially experiments in moving people. The ingenious water channel system created for Pepsi would become the hallmark of Disney’s magnum opus, Pirates of the Caribbean; the Modern Marvel: Carousel of Progress remains one of the highest capacity attractions Disney has ever built…

…bested only by the ride system pioneered on the Magic Skyway. This sensational World’s Fair classic would place guests aboard real Ford convertibles – right off the assembly line! – with no motors. Those cars would be gently and continuously propelled along elevated highways along the exterior of the Ford pavilion before passing into the building’s interior. There, WED designers had created the largest Disney ride of Walt Disney’s lifetime.

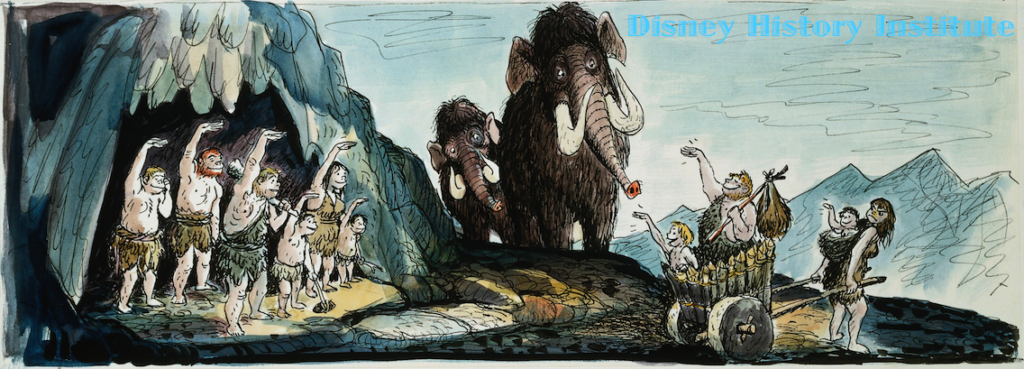

Those Ford cars would pass through prehistoric jungles, past scenes of wading sauropods, a family of triceratops and a battling stegosaurus and T. rex before passing forward in time past scenes of early man hunting mammoths and finally on to the cities of tomorrow. Those scenes were storyboarded and designed by Disney Legend Marc Davis – an animator-turned-Imagineer who Walt often regarded for his ability to construct memorable characters and perfectly-staged scenes.

The Ford Magic Skyway made it back to Disneyland in pieces. Some of its 64 Audio-Animatronics dinosaurs were placed along the Disneyland Railroad while the Magic Skyway’s high-capacity, high-efficiency transportation technology ride system was exported to Disneyland as the Lost Legend: The Peoplemover!

Experimental Prototype Community of Transportation

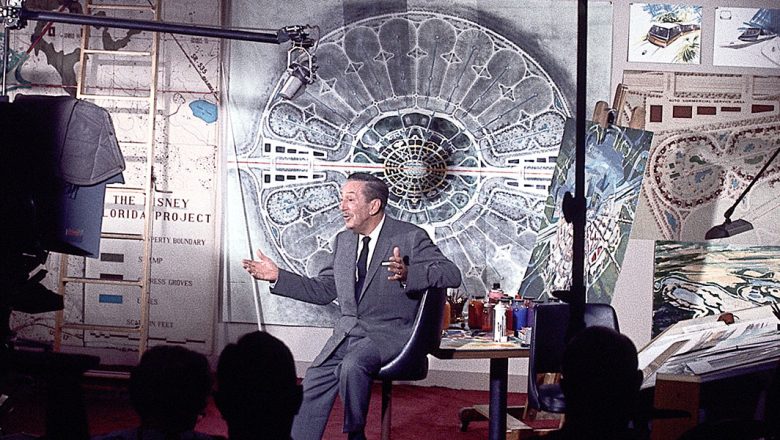

In fact, when the Peoplemover returned to Disneyland as a centerpiece of the park’s New Tomorrowland in 1967, it wasn’t just as a ride; it was as a prototype. Like the Monorail and the Lost Legend: The Skyway that had been gracing the skies of Tomorrowland since the ’50s, Walt’s hope had been that the transportation technologies staged as mere attractions at Disneyland would be applied in E.P.C.O.T. – a living, futuristic city he expected to build in Central Florida.

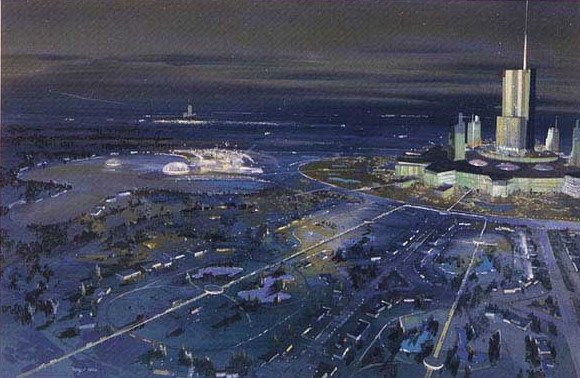

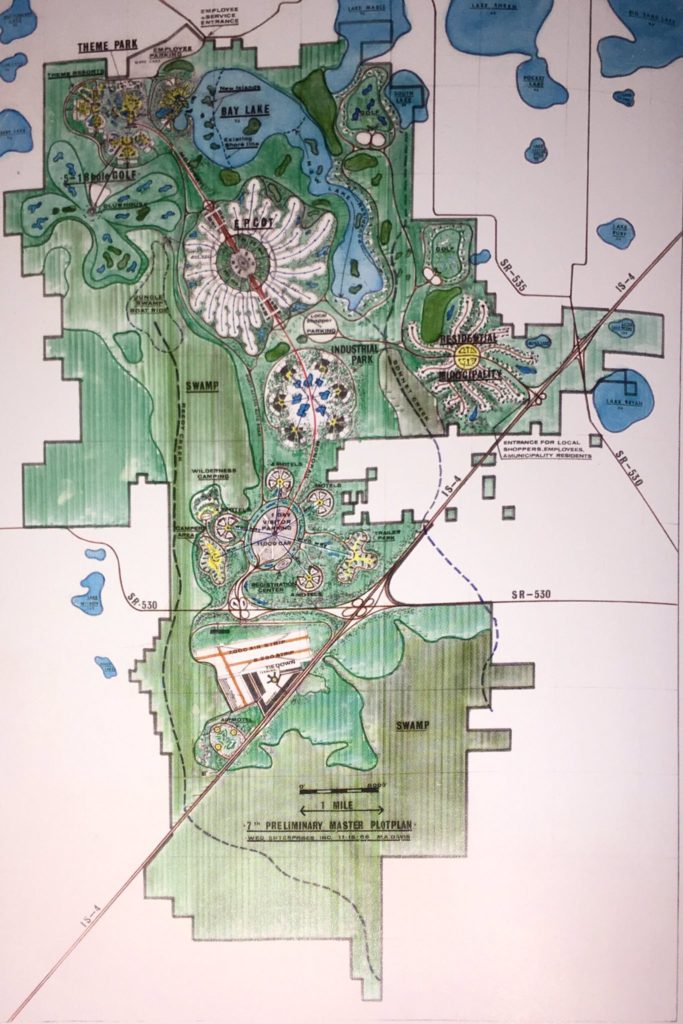

Walt intended for this EPCOT to singularly redefine urban living – a radial city with an enclosed pedestrian urban city center, a “green belt” of parks, schools, stadiums, churches, and community centers, and an outer ring of residential areas. This real city would’ve been a blueprint for the future; a radical reinvention that would shape the evolution of any modern city that would come after it.

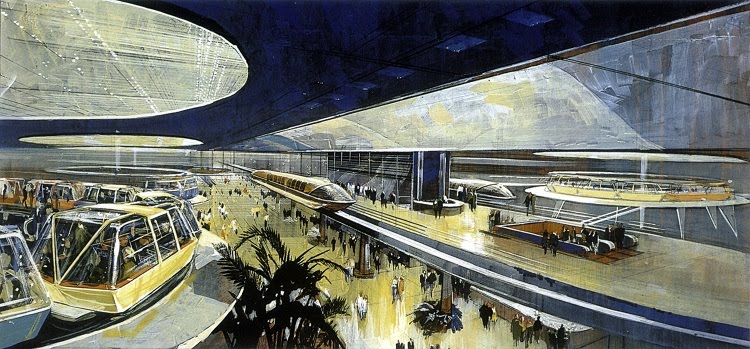

But the keystone of EPCOT would be its transportation – a cutting edge network would criss-cross the symmetrical city. The (few) highways and roadways that entered the city would be buried far from pedestrian traffic, leading to massive parking decks at the city’s core under the 30-story hotel. Externally, the city would be connected to the outside world via none other than the monorail. The monorail line proposed would have stops at the Airport of Tomorrow (to be built just outside the city), the Disney World Welcome Center, EPCOT City, and – last stop – Magic Kingdom.

Once riders arrived at the city of EPCOT, they would disembark from the monorail and transfer to sleek, pollution-free Peoplemovers that would transport folks from the city center to the outer ring of residential areas, like arteries circulating to the finer points of the city. These Peoplemover paths would diverge from the city center and reach to all corners of the circular metropolis. Continuously moving, these constant cabs would keep traffic flowing day and night.

In EPCOT, the rides of Disneyland would be real; essential, practical applications sincerely put to work. Not as models, but as the start of something new.

EPCOT Center

Walt’s brother Roy stated that as Walt lay dying of lung cancer in the hospital, he was still planning his EPCOT metropolis, using the ceiling tiles of the hospital room as a grid to plot the city’s layout. Unfortunately, Walt died on December 15, 1966 – long before any part of his “Florida Project” could come to fruition.

The earliest steps of EPCOT did come to pass, as Florida’s governor Claude Kirk Jr. signed a law establishing the Reedy Creek Improvement District, effectively giving Disney governmental control over itself. Ultimately, Disney’s remaining leaders decided that the idea of building a city was simply too risky without the man who’d so passionately spearheaded the project. Still, Disney did go forward with building Magic Kingdom, and Roy insisted that this Disney World be renamed Walt Disney World as a tribute to his brother, opening in 1971.

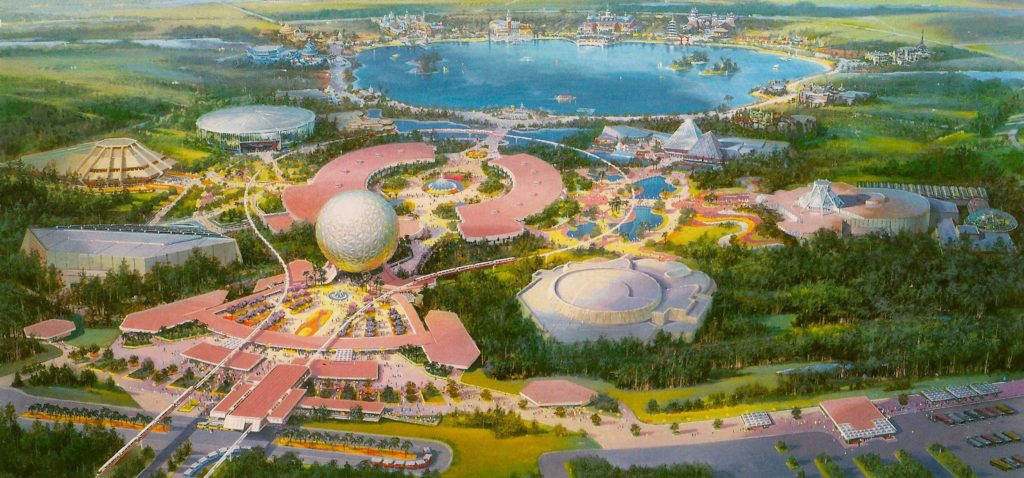

The city of EPCOT was not to be. Instead, in the late 1970s, then-CEO Card Walker proposed a new take on EPCOT – a second theme park for Walt Disney World. This new adaptation wouldn’t be the city Walt dreamed of, but it would work off of his ideals and his fascination with futurism and the power of American industry. That’s how the ambitious, progressive model of EPCOT merged conceptually with Disney’s long-running interest in building a permanent World’s Fair.

EPCOT Center would be the best of both worlds, inviting corporations to showcase their cutting edge technologies in pavilions focused on science and industry; a permanent World’s Fair theme park dedicated to innovation.

Transportation would be an indelible piece of EPCOT Center, too. Sure, a new monorail spur route was diverted off to the south to circle the park’s “World’s Fair” style icon, Spaceship Earth. But transportation would also be selected as one of the park’s core areas of industry. Alongside energy, ocean, land, heath, imagination, communication, and innovation, and entire pavilion would be dedicated to transportation and its incredible living history.

On the next page, we’ll dig into World of Motion. Read on…

With the recent news about Test Track 3, will we be getting a History in Motion part 3? Looking forward to it!