“Welcome one and all! Y’all come have a ball! Things are very fine, riding on the ole’ Knott’s Bear-y line!” It’s not every day that an attraction manages to truly capture a generation. It’s even rarer that one of those good, old-fashioned family attractions becomes so legendary, its story outlives its lifetime. Yet today, we’re inducting just such a classic into Park Lore’s library of Lost Legends.

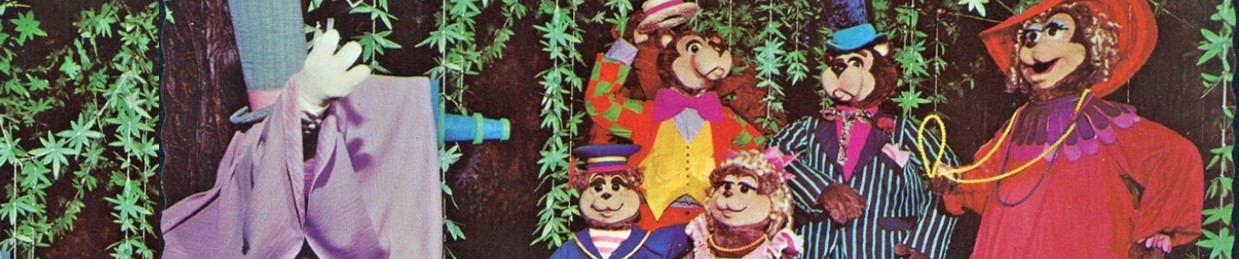

Original characters created by one of Disney’s most legendary designers? Check. A memorable and melodic singalong musical score? You bet. Iconic environments plucked right from a storybook? Uh huh. Enough nostalgic wallop to enchant millions of Southern Californians over a decade-long life? Yes indeed.

While those ingredients may sound like the making of the kind of fairytale dark ride you’d expected to find in Fantasyland, Knott’s Bear-y Tales wasn’t a Disney attraction at all. Instead, it could only be found at Knott’s Berry Farm – just a few blocks north of Disneyland in Buena Park, California. How did one of Disney’s most esteemed Imagineers create an attraction that became a Southern Californian treasure? And how has the concept made a miraculous return? Well, let’s just say… it’s kind of a cute story…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

Knott’s Berry Farm

Disneyland may indeed be the place where the “rules” of the modern theme park were born in master-planned form. But make no mistake – Walt Disney knew exactly who he was taking his cue from: Walter Knott.

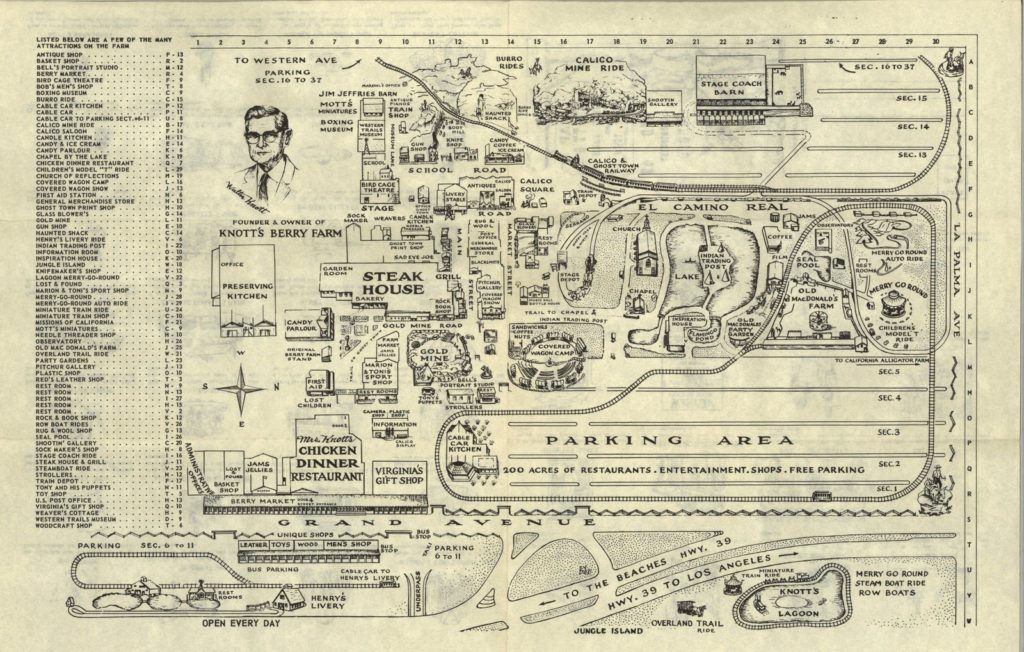

Technically, Knott’s Berry Farm traces its history to 1920, when Walter and his wife Cordelia drove their Model T Ford to Buena Park, California, renting real estate to restart their lives as farmers. By 1927, they’d built a home and berry stand on the land, plus a Tea Room for Cordelia to sell sandwiches, jams, and homemade pies baked fresh with the farm’s berries.

In 1934, Cordelia decided to weather the Great Depression by using the farm’s bounty to open her Tea Room up for full-service dinners. Mrs. Knott’s fabled fried chicken dinners came complete with salad with rhubarb, biscuits, vegetables, mashed potatoes with gravy, and berry pie for dessert, all for 65¢. In a matter of years, the 20-seat Tea Room became a 350-seat Restaurant with multi-hour waits each evening…

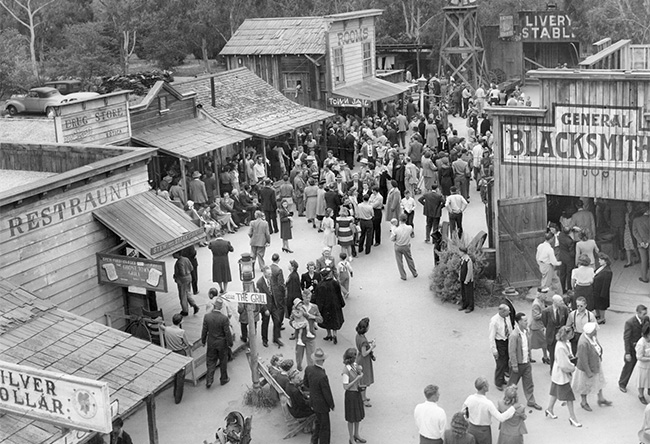

Walter began building a historic 1860s Western mining town – one shop at a time – in 1940 merely as a way to entertain crowds waiting for a table! By the middle of the decade, however, Knott’s “Ghost Town” was an attraction in its own right. In 1947, the Knottses officially established “Knott’s Berry Farm” as a roadside attraction, where guests could buy souvenirs, pan for gold, indulge in chicken dinner, and taste the legendary “boysenberry” cultivated by Knott and fellow farmer Rudolph Boysen (from a little rural neighborhood a few miles south called Anaheim).

Knott’s Berry Farm still bills itself as “America’s First Theme Park,” and it’s easy to agree. When Walt Disney arrived in town in the 1950s, Knott’s Berry Farm was already a destination! More to the point, Walt often spoke with Walter Knott about his park’s capacity, traffic flow, pricing, and more, all in an effort to refine the “Magic Kingdom” being built down the road.

Everything changed at Knott’s Berry Farm with the arrival of Bud Hurlbut in 1960, whose handshake deal with Knott lead to the construction of two pivotal attractions (and two of the most magnificent classic dark rides in the industry): the Calico Mine Ride and Log Flume – each quite literally an inspiration to Walt Disney, leading directly to his own Lost Legend: Mine Train Thru Nature’s Wonderland (and the idea of a hidden queue).

So you can imagine that even if Disneyland is given due credit for being the first master-planned, intentional theme park, Knott’s was undoubtedly its progenitor. Especially in those early days of the 1950s and ’60s when both Disneyland Knott’s Berry Farm were growing thanks to the talents of the first generation of artists-turned-attraction-designers, everyone was learning as they went.

One of those early Imagineers in particular would become the star in our story today…

Pencils, Paperclips, Propellers, and Pot

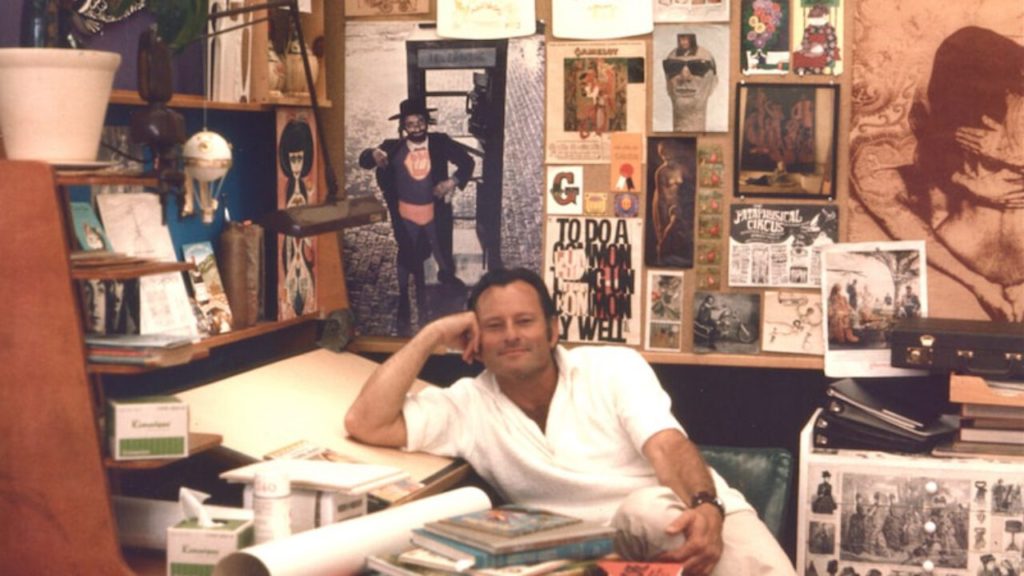

There’s probably no prelude to a career at WED Enterprises as unusual as that of Rolly Crump. Though he began his career as an animator at the studio on films like Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, and One Hundred and One Dalmations, the countercultural artist’s entry to Imagineering was likely jumpstarted by pot.

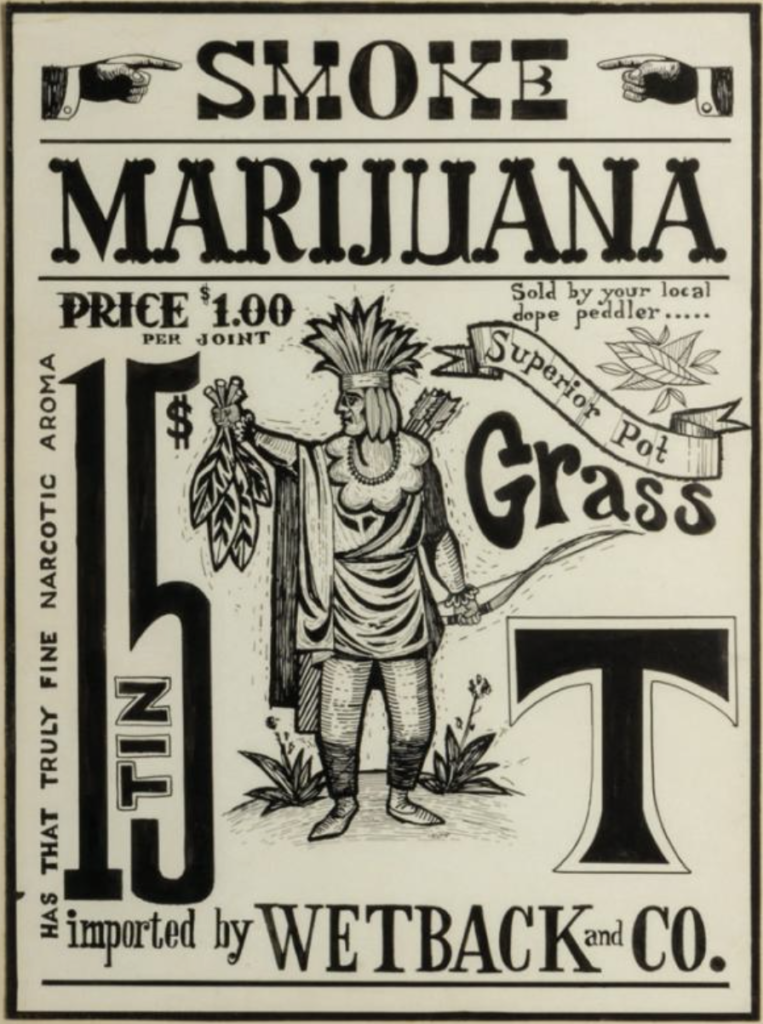

In the early 1950s, Crump hand-drew a series of “Doper Posters,” humorously advertising illegal drugs like heroine, cocaine, opium, and marijuana in the style of late-1800s poster ads. Though he submitted the posters to the Studio’s art show, he hardly expected Walt to see them. “When I heard that Walt had seen my marijuana poster, I was horrified because I didn’t know how he would react,” Crump wrote in his 2012 autobiography, It’s Kind of a Cute Story. “But I was told he laughed, which goes to show you that Walt had a great sense of humor and would accept anything his artists did if they were trying their best.”

Pencils and paperclips, you might say, were the final straw. Always a tinkerer, Crump would use simple office supplies to create kinetic sculptures, filling his room at the studio with paperclip-powered propellors that would spin in the breeze from the air conditioner. When fellow animators convinced Rolly to install his spinning supply sculptures in the Studio’s library, Walt stumbled across them. And just like that – like so many standout animators at the Studio during the ’50s – Crump was called over to WED Enterprises to lend his distinctive style to Walt’s new pet project… a new kind of amusement park.

“When I finally worked for Walt, I think it was the propellers that made him want to hire me,” he wrote. “I think he liked my imagination.”

Perhaps the perfect embodiment of that imagination (and in many ways, of Crump’s pencil-and-paperclip propellers) was his most distinctly-“Crumpian” project for Imagineering: the magnificent Tower of the Four Winds that served as the icon and marquee of “it’s a small world” at the 1964 – 65 New York World’s Fair. A spectacular, 110-foot tall emblem of the Pepsi-Cola pavilion, the Tower was adorned with spinning umbrellas, rotating windmills, and revolving flowers – a giant, delightfully-kinetic, mid-century masterpiece. (Unfortunately, the Tower of the Four Winds was far too large to ship back to Anaheim when the rest of “it’s a small world,” so it was left in Queens and eventually demolished and sold for scrap.)

Of course, Crump did design its spiritual successor – the iconic, Mary-Blair-inspired clocktower, glockenspiel, and geometric facade that serve as the ride’s exterior in California, Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong. With his distinct touch of motion, shape, and joyful whimsy, the pop-up book stylized architecture is “Crumpian” to the core.

Likewise, Rolly’s touch can be sensed if not seen all around Disneyland. He designed, sculpted, and hand-painted most of the tikis in the lanai garden of the Modern Marvel: The Enchanted Tiki Room. (Rolly told his hometown paper, the Fallbrook Village News, that it was his idea to dangle sequin “Sparkletts” in the eyes of the tiki drummers in the show so their eyes would glisten as they drummed.) He built “small world’s” North Pole scene (which was original to the park and hadn’t been featured in New York). He was also a leading designer behind the Lost Legend: Walt’s New Tomorrowland and its kinetic, “World on the Move” spirit.

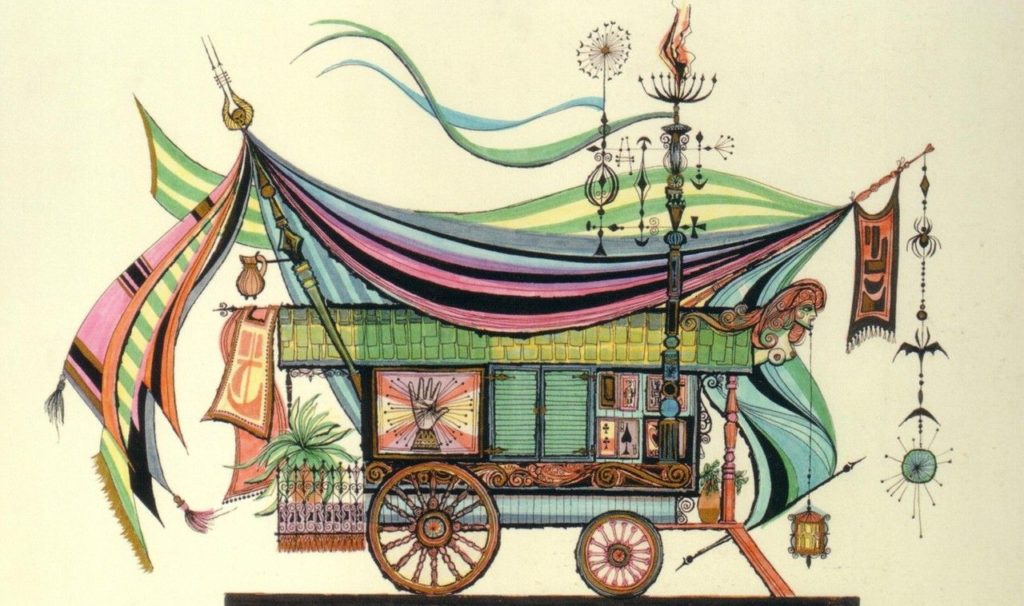

Interestingly given our subject today, back when the jury was still out on what the Haunted Mansion ought to contain, Crump’s concept was a “Museum of the Weird” packed with otherworldly oddities, international wonders, eclectic designs, paranormal sights, strange creatures, palm-readers and vardo wagons (left), and living antiques – elements of which still live on in the Mansion’s final form. (We explored the “Museum of the Weird” concept more deeply in our look at its own “spiritual successor,” the Modern Marvel: Mystic Manor and in our Extra Feature list of proposed restaurants inside of rides.)

Like Marc and Alice Davis, Claude Coats, Bob Gurr, Mary Blair, John Hench, X Atencio, and so many more “first generation” Imagineers, Rolly Crump was absolutely instrumental in many of the conversations and conventions that shaped Disneyland. He often referred to Disneyland as a “gorgeous salad,” in which he and his contemporaries were invited to bring their unique talents and styles, pursuing passion projects; where their dissimilar “parts” combined into a complete “whole.” To that point, “Crumpian” flavor still abounds within the park! But unlike his contemporaries – many of whom would spend the rest of their careers with Disney – Crump felt propelled forward.

The Right Time & Place

Though he contributed to the early designs of Magic Kingdom, it’s fair to say that Rolly Crump quickly became disillusioned with the increasingly corporate structure of Disney after Walt’s death in 1966.

Through Crump’s point of view, it’s easy to imagine why. Unlike the “gorgeous salad” of Disneyland with its empowered Imagineers and its spirit of invention and chance, Magic Kingdom would be defined by pre-planning and operational optimization. Individual contributions, styles, and flavors would be downplayed in favor of a homogenized brand, deference to a corporate stylebook, and by-the-numbers attraction lineup where risks and reinventions would be few and far between.

Crump said of the Floridian park in a 2018 interview with the LA Times:

“It had no feeling of Disney. […] Disneyland has charm. Disneyland freaking hugs you and kisses you. […] When you go to Disney World and you see the castle, you want to genuflect. And that disturbed me. […] I helped design the rides at Disney World, but we lost the charm. […] The whole thing fell apart. I quit.”

By 1970, Rolly Crump was a free agent. He started his own attraction design and fabrication company – Design 27 – to serve the emerging, modern, post-Magic-Kingdom themed entertainment industry.

And wouldn’t you know it? Right about then, back at Knott’s Berry Farm, Walter and Cordelia’s daughter Marion had stepped up and overtaken the family business. With big plans for her father’s Ghost Town, she set out to find talent that could usher in a new era of attractions, including a spectacular new dark ride. Read on…