Rocketing toward razor sharp icicles, hanging face-first over bubbling lava pits, dropping through fog from volcanic vents, escaping death at the hands of a menacing lost goddess… Sounds like the kind of production only Disney or Universal could manage, right? But this stunning attraction based on an internationally renowned franchise was located in a most unexpected place… The Midwest. And what’s more, this one-of-a-kind dark ride was so mysterious – its secrets so well-guarded – that guests didn’t know what kind of ride it was, even once they were seated and strapped in.

And with that promise, we can set course for another entry in our Lost Legends series. From The Peoplemover to Alien Encounter; 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea to Journey into Imagination and dozens more, we’re on an international Imagineering expedition of our own, telling the incredible tales behind closed classics and fan-favorites. And while it’s not often we find an attraction exceptional enough to inspire a trip outside of the destination parks we know and love, this one is worth the journey into the unknown…

Today, we’re going to go behind-the-scenes of one of the most mysterious and unique rides to have ever existed at all, much less outside of Disney or Universal’s watch. In 2002, Paramount’s Kings Island near Cincinnati, Ohio became home to TOMB RAIDER: The Ride. At more than $20 million, this blockbuster attraction exceeded all expectations of what a seasonal theme park could produce. And barely a decade later, it was gone forever. How? Let’s unearth the ruins of this Lost Legend together…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

The adventure begins…

As difficult as it may be to imagine today, there was a time before Disneyland; a time when the “rules” invented by early Imagineers had yet to be developed. The fundamentals we associate with amusement parks today – a single point of entry and exit, an entry area lined with retail and dining, “themed” areas radiating out from a central core, and, yep, even an entry fee – simply didn’t exist. So while “amusement parks” have existed since the latter half of the 1800s (likely spurred by the origin of World’s Fairs in the 1850s), they didn’t look much like the parks we know today.

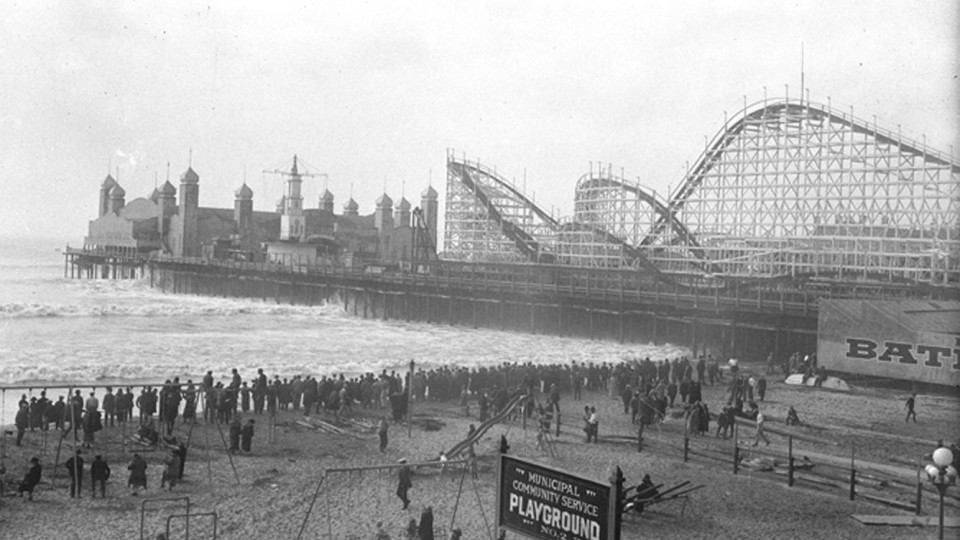

In fact, a generation of parks were born from the nascent age of pleasure resorts along the coast. The idea of seaside boardwalks and amusement-filled piers dates to the late 1800s, when steam-powered carousels and rudimentary, gravity-powered “switchback railways” delighted visitors. With the advent of electricity at the turn-of-the-century, those boardwalks became strung up with electric lightbulbs, gaining games, thrill rides, and competing vendors. (You can still see this kind of park flourishing today in New York’s Coney Island, Blackpool Pleasure Beach in the U.K. or the Santa Monica Pier in California.)

Not so different was a generation of amusement parks evolved from trolley parks – picnic and recreation areas often situated at the end of city’s street car lines (and in fact, they were often created by streetcar companies to increase ridership on weekends).

While not as grand as the seaside parks, a trolley park typically offered city dwellers some combination of sports fields, a “sunlite” swimming pool, a theater, boat rides, and – most memorably – an elaborate dance hall. As a matter of fact, it’s estimated that at their peak in 1919, more than 2,000 trolley parks were spread across the United States, though just a handful survive from the era today.

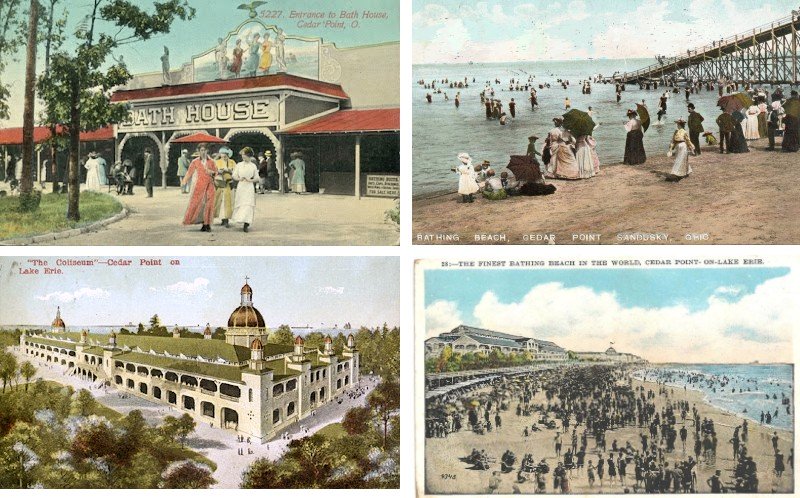

Where they do survive, you may not immediately recognize them! After all, decades and decades of development saw surviving trolley parks add merry-go-rounds, Ferris wheels, and wooden roller coasters, gradually evolving into parks like Waldameer, Kennywood, and Dorney Park. While the postcards above may not look much like the Cedar Point you recognize today, they’re all nonetheless remnants of the original look and feel of that 150-year-old park in Sandusky, Ohio whose main attractions used to be sunbathing and dancing!

Open to the public with no set entrance or entry fee, these park often developed “rough” reputations thanks to wayward youth out to cause trouble, competing vendors nickel-and-diming guests, “carnie” atmospheres, and loud, unsafe rides.

Put another way, for most of their history, amusement parks weren’t the kind of thing a reputable businessman would be interested in… which is why, in the 1950s, when Walt told his wife Lillian he intended to open his own, she said, “Why would you want to involved with an amusement park? They’re so dirty, and not at all fun for grown-ups. Why would you want to get involved in a business like that?”

He’s said to have replied: “That’s exactly my point. Mine isn’t going to be that way. Mine’s going to be a place that’s clean, where the whole family can do things together.”

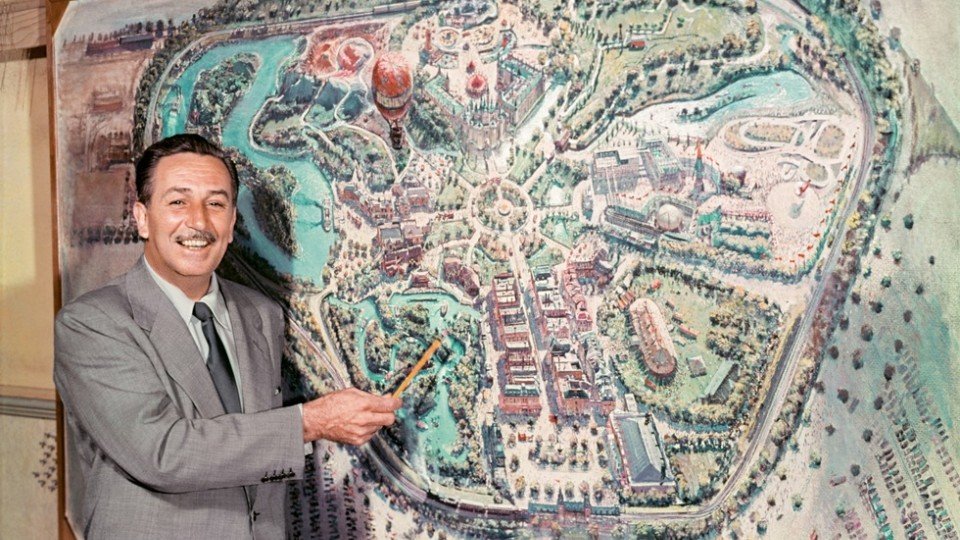

And he was right! Disneyland had a single entrance and exit blocked by ticket booths requiring payment for entry; it wasn’t inhabited by competing vendors, but designed by filmmakers. And unlike those parks that had developed over decades and decades, Disneyland had the benefit of master-planning, evident in its famed “hub-and-spokes” layout, pulsing all guests to the park’s center (and a towering park icon) from which themed lands radiate like spokes on a bicycle tire.

That’s why Disneyland is considered a pivotal moment in not just “amusement parks,” but in urban planning and entertainment design. Suddenly, the long, stretched midways dotted with random rides and amusements was no longer the de facto model. And so it’s no surprise, any new parks coming online after Disney’s would borrow from its success…

Lessons learned

Here’s where the story of Kings Island – and its eventual blockbuster dark ride – begins in earnest. During the 1950s, Walt set off on a tour across the U.S. and Europe, visiting amusement parks of the era to gather advice for his Disneyland. One of those stops was Cincinnati, Ohio’s Coney Island (not to be confused with New York’s), where Walt cut a check for $1.00 for “consulting services” (still in the park’s archives) before departing.

Coney Island traced its origins to 1886 – a very long time ago, even to Walt Disney – and had managed the increasingly difficult task of surviving through World War I and World War II. However, a series of devestating floods of the neighboring Ohio River in the 1960s had crippled Coney Island, after being submerged under 14 feet of water in 1964, there was no denying: the park needed to relocate to survive.

Given the chance to start fresh, this new park could adapt all that had been learned from Disneyland; it could be among the first in a next generation of Disney-inspired parks leveraging those now-tried-and-true trademarks, like a hub-and-spokes layout, a “Main Street,” and a central icon.

And like Disneyland, it could even feature characters and stories people loved. How? By 1968, Coney Island’s owners were in talks with Taft Broadcasting, a media company who were eager to leverage their recent acquisition of Hanna-Barbera (the animation studio behind The Flintstones, The Jetsons, Scooby-Doo, The Smurfs, and more).

In July 1969, Taft Broadcasting Company purchased Coney Island for $6.5 million, then purchased 1,600 acres of land northeast of Cincinnati in Mason, Ohio.

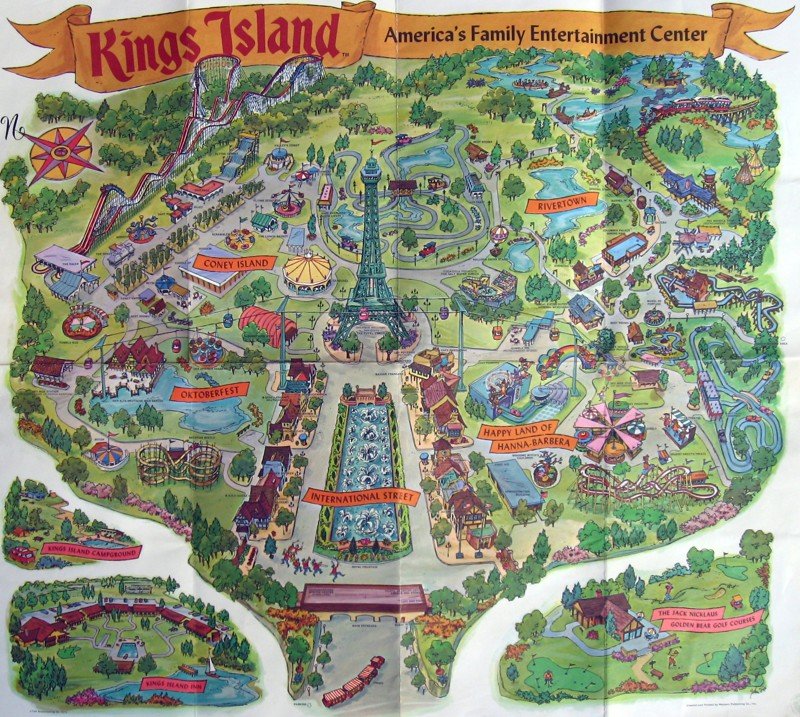

When Kings Island opened in April 1972 (just six months after Walt Disney World, mind you), it was a park borrowing from Disney’s innovation. Guests entered the park via International Street, walking down its corridor of leaping Royal Fountains and European old-world architecture to the base of a 1/3 scale Eiffel Tower (more than 300 feet tall). From that central hub, themed lands radiated off.

There was Oktoberfest (a German land anchored by a beer garden and flat rides, and later by the Festhaus stage and restaurant), Coney Island (populated by all of the relocated rides from the old park), Rivertown (a forested Ohio settlement), and the Happy Land of Hanna-Barbera (a veritable Fantasyland of family fun).

When Kings Island opened, its two headlining attractions were undoubtedly the dual, white tracks of the Racer (credited with sparking the Second Golden Age of the Roller Coaster, and famously ridden by The Brady Bunch in their 1972 episode, “The Cincinnati Kids”) and Happy Land’s Enchanted Voyage dark ride through Hanna-Babera’s cartoon worlds – surely one of the best dark rides on the planet at the time.

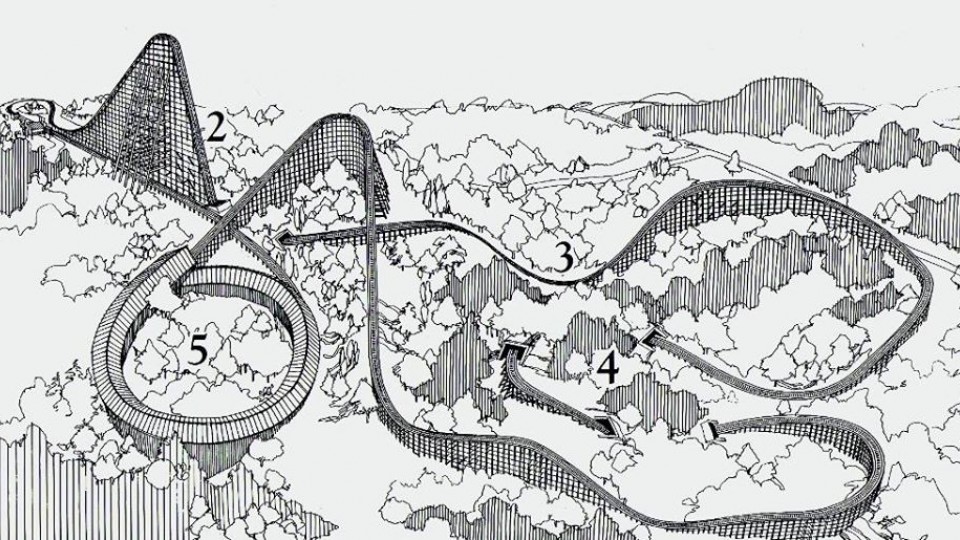

Kings Island’s most famous attraction, though, was born in 1979. That’s when Rivertown – that rustic old Ohio settlement village – gained a strangely dark new mythos by way of one of the most legendary roller coasters on Earth: The Beast. At 7,359 feet and with a ride time well over 4 minutes, The Beast was (and is still today, more than 40 years later) the longest wooden roller coaster ever.

Covering more than 35 acres, The Beast roars through the expansive, endless forests beyond the park, hemmed to the ground as it follows the terrain through tunnels and caves, shuddering through the trees… Ever unseen, The Beast’s track is famous for being nearly invisible from the park (except for its lift hill) and for its night rides, howling through the pitch black woods as trees race past in the darkness.

This much is clear: over its lifetime, Kings Island – the modern park that emulated Disney’s greatest elements – grew and added new themed lands, stellar dark rides, wild, well-themed family roller coasters, and more. But the park’s Disney-esque design principles were only the start, as a new era in the theme park industry made Kings Island an attractive acqusition for a movie studio looking for parks of its own… Read on…