Modus operandi

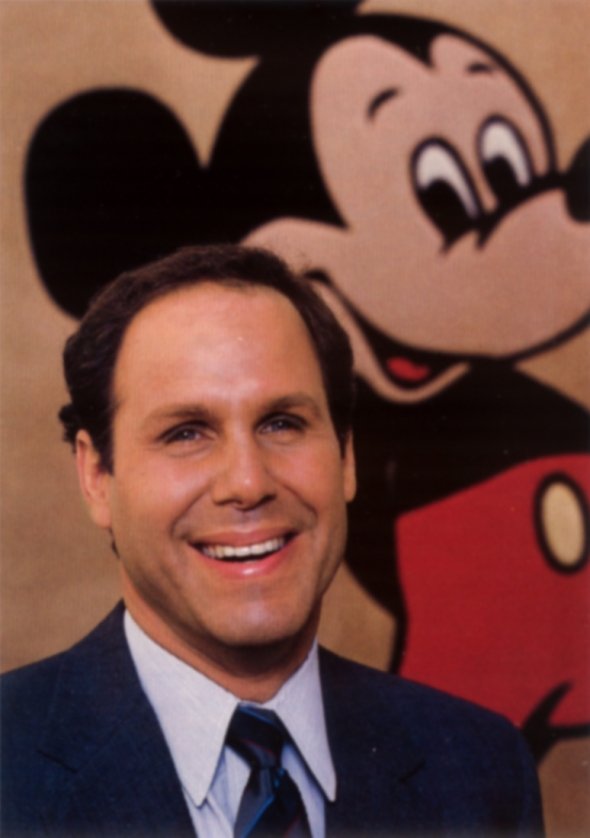

This is when we arrive at a common juncture in so many of our in-depth features. Frequent readers of our Lost Legends series know that so many tales revolve around the introduction of perhaps the most controversial figure in Disney history. And once more, our pivot point is Michael Eisner.

For more than a decade following Walt’s death, Walt Disney Productions had rusted. Its once-golden name was tarnished; its studios had gone years between blockbuster hits; its theme parks were stagnating as tired, dusty remants of another era. But when Eisner arrived as the CEO of Walt Disney Productions – hand-picked by Roy O. Disney, Walt’s nephew – he brought with him an extensive and important history as CEO of Paramount Pictures. Eisner had exactly the experience and insight necessary to revive Disney’s studios and – by extension – its parks.

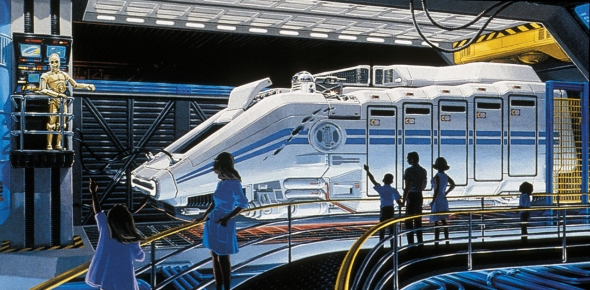

Eisner was eager to inject some much-needed vitality into the dusty Disney Parks, even if it meant forging partnerships with brands beyond Disney’s catalogue.

As luck would have it, George Lucas – creator of Star Wars and, thus, preeminant filmmaker of the time – was eager to work with Disney, and hit the ground running with a series of can’t-miss Lost Legends: Captain EO, STAR TOURS, and The ExtraTERRORestrial Alien Encounter, each in turn making Disney Parks into cool, hip, edgy, cinematic, popular places in touch with current pop culture, modern movie stars, famous filmmakers, and hot music.

Eisner’s faith in the power of cinema ran so deep, he proposed a pavilion for EPCOT Center based on the filmmaking industry (elevating it stand alongside oceans, energy, imagination, transportation, agriculture, and communication) before ultimately deciding that it deserved more – an entire theme park dedicated to Hollywood, its history, and the magic of moviemaking… The Disney-MGM Studios.

He also believed that Disney’s spectacular storytelling and commitment to theme might also crack the problem of the longstanding Walt Disney World Village shopping district… Though he had a little inspiration.

Competition

Just up the road from Walt Disney World, a new attraction was gaining steam. The old Church Street Station in Downtown Orlando was constructed in 1889 by the South Florida Railroad, operating as a train station until its closure in 1926.

But during the 1970s, an intentional revitalization saw the old railway station transformed into a new entertainment center populated by nightclubs. Spanning both sides of Church Street and both sides of the railroad tracks, Church Street Station became a bustling, go-to hangout for young people who could pay a single price to club-hop between its nightclubs.

Believe it or not, in 1985 alone, Church Street Station had 1.7 million visitors, making it the fourth biggest tourist attraction in Florida by attendance after Disney World, SeaWorld, and Busch Gardens (but beating Cypress Gardens, Gatorland, Weeki Watchee Springs, and many others).

Eisner and his team saw the nightclub entertainment complex as a viable option for import to Walt Disney World, and supposed that it might be the way to finally draw guests in sizable numbers to the once-marooned Shopping Village far off in the resort’s southeastern corner. Plus, a collection of clubs would help Eisner on his longstanding goal: to make Disney Parks hot, trendy places that appealed to more than simply families with young children.

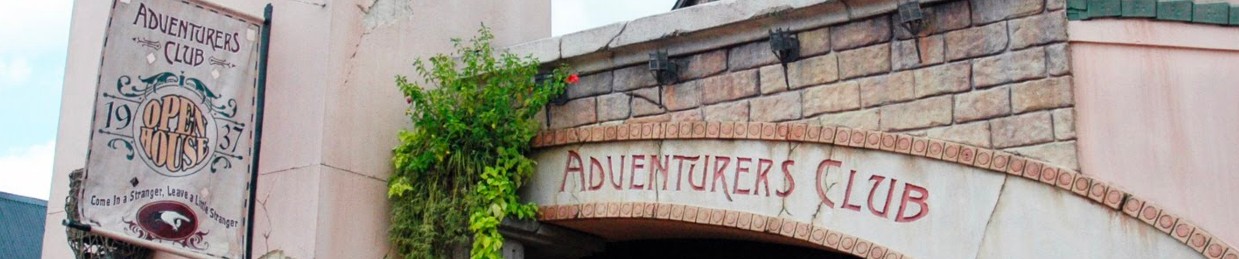

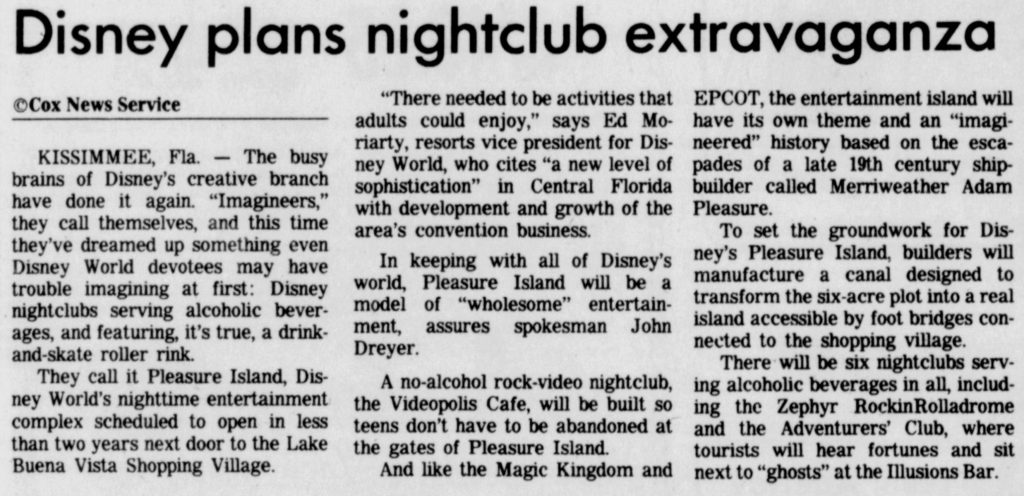

It’s no coincidence that in 1986, Disney announced that a set of adventurous Imagineers had “stumbled” upon the long-lost, overgrown remains of Pleasure Island mere feet away from the Walt Disney World Village…

Pleasure Island

Alright, so the “history” of Pleasure Island we noted earlier is more Disney fantasy than fact. But this, Eisner supposed, was the key to Disney’s own club-hopping, adult-oriented nighttime entertainment center. To his cinematic thinking, the phony story of Merriweather Pleasure and the grand, heralded “rebirth” of Pleasure Island as a club-hopping venue was exactly the “Disney touch” to set Pleasure Island apart…

In so doing, Pleasure Island would also capitalize on the “adaptive reuse” trend that was only beginning to sweep the country, wherein abandoned industrial warehouses and long-vacant urban factories would be repurposed as art collectives, bars, breweries, and clubs… an urban design strategy still widely in use today.

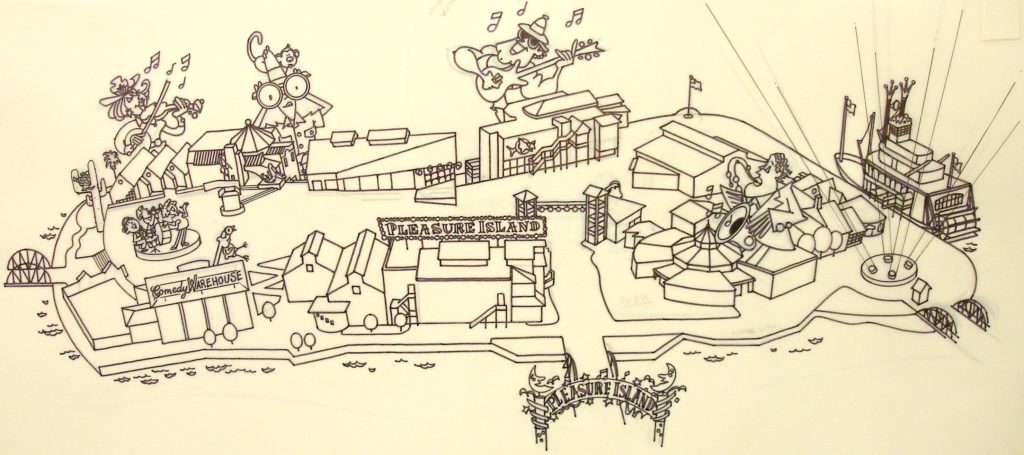

Pleasure Island would look like a historical world built over the course of decades, with each and every square foot explained by some piece of the massive, connected frame-story of Merriweather Pleasure – from hidden hints and vague clues to outright obvious architecture. Pre-dating (and by most accounts, dwarfing) Disney’s best examples of overarching, land-wide continuities (arguably, Magic Kingdom’s New Tomorrowland and Disneyland’s Adventureland renovations, both in 1995), the scale of Pleasure Island’s story was so massive – perhaps too massive – that most people might miss it.

But by purchasing a ticket to Pleasure Island, you wouldn’t just visit bars, clubs, and restaurants, you’d be stepping into the story of the Pleasure family and their cross-continental journey; you would see, feel, touch, and hear the history of the island as you journeyed between the old Merriweather mansion (now “repurposed” as the Portobello Yacht Club) and the docked paddlewheeler he arrived aboard (now Fulton’s Crab Shack), the infamous Fireworks Factory (“built in 1924” by Merriweather’s Chinese connection), the canvas fabrication plant (housing the Mannequins nightclub), or the island’s power plant (now home to the Comedy Warehouse).

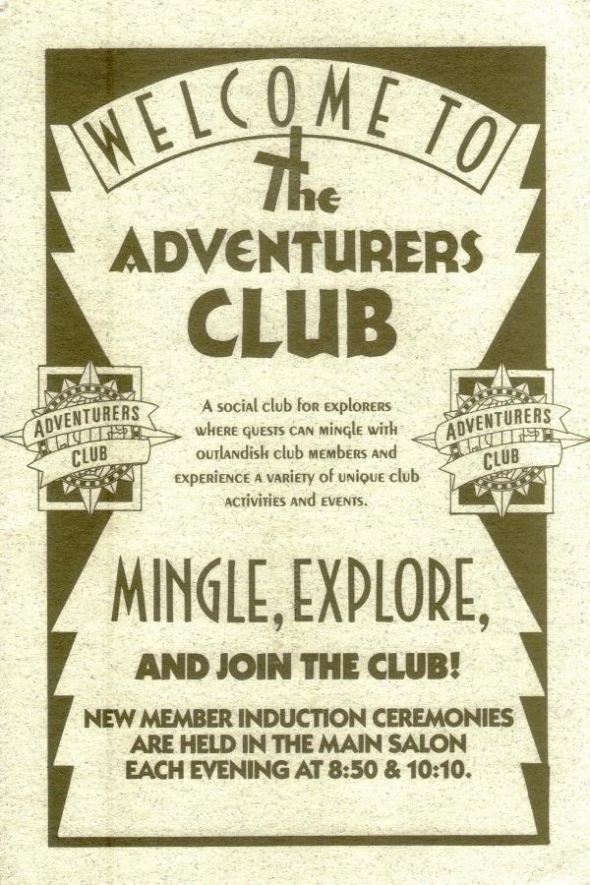

Already, perhaps you’re getting a sense of the “living story” of Pleasure Island; like the immersive theater experiences cropping up around the world today, by stepping onto Pleasure Island, you were becoming part of a story; if you like, solving a mystery by exploring the island’s “histerical society” plaques, connecting modern clubs to what they were “originally,” and seeing what became of Merriweather Pleasure and his family.

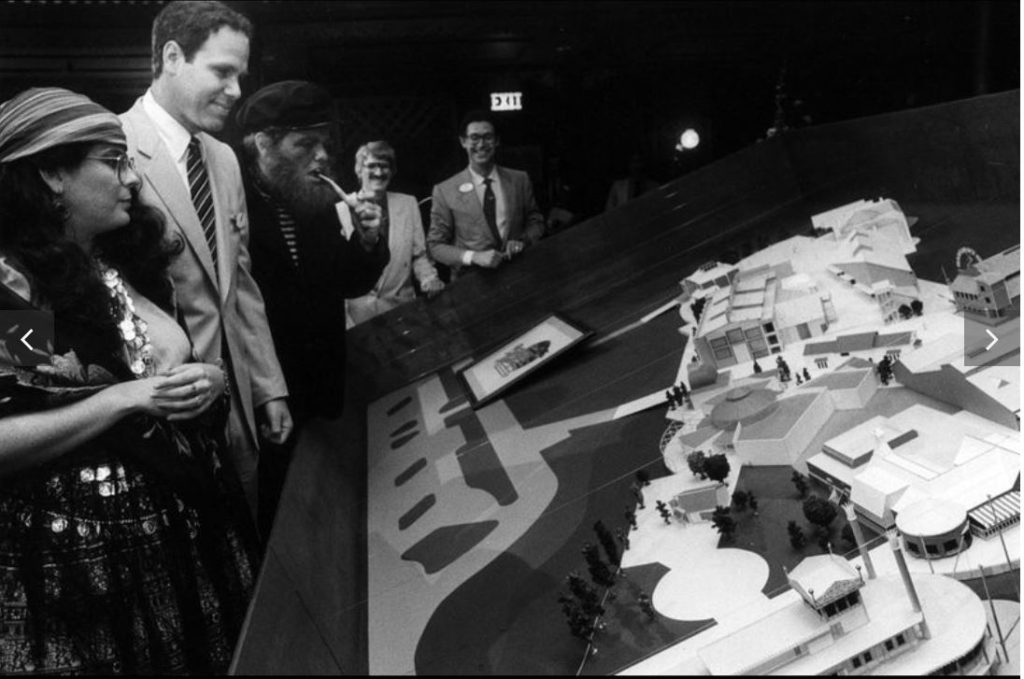

Founding

So even if Disney’s new Pleasure Island looked a century old, that was exactly the point. And there, amid this vast island of world-building and immersive storytelling stood a new kind of experiment…

As the story goes, two prominent figures in Imagineering are the focal points of the Adventurers Club’s founding. Chris Carradine – at the time, Vice President of Walt Disney Imagineering – supposedly came up with the idea and sketched it out on cocktail napkins in a New York City restaurant one evening.

He proclaimed that it would have “twice as many rooms as guests will ever see,” referencing the tremendous world-building backstory and the sense of place. In fact, the building itself was constructed with space to add new rooms as the Club grew.

Carradine was also a frequent audience member at the Los Angeles stage production Tamara that premiered in 1981. Famously dissolving the boundary between spectator and actor, Tamara invited 150 viewers onto (or maybe, into) the stage, freely flowing between eleven rooms designed to resemble an Italian villa, interacting at will with a dozen actors in a live, immersive theater… a kind of entertainment not yet commonly known.

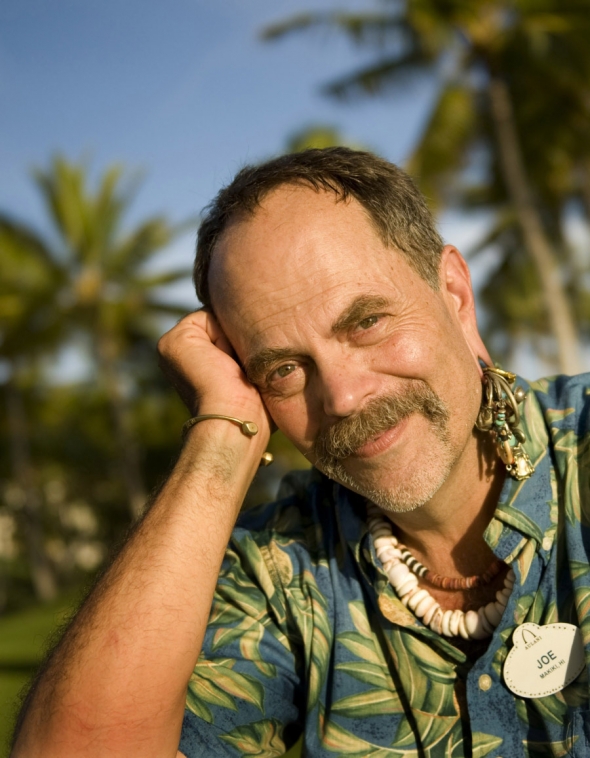

Another leading figure we’ve already mentioned – Joe Rohde, of Disney’s Animal Kingdom and Aulani fame – is said to have inspired the Club’s atmosphere by throwing an annual Sunday afternoon theme party he called “The Last Days of the Raj” wherein Rohde and his friends and colleagues would dress in British colonial attire. Or, as one of the Club’s actors, Craig McNair Wilson told MousePlanet, “it came out of our collective, shared love of the world of the pith helmet and all that circled around it. It was the place we always wanted to go, but it didn’t exist.”

Ah, but now, it’s time to journey on. Remember Pleasure’s library, custom-built to contain the vast wonders of his artifacts and collections? By stepping inside, you become an explorer; an actor; an inventor; a part of the story. And on the next page, we’ll finally rejoin the Adventurers Club.