Busch Gardens

Born in the ’80s and ’90s, the “Ride the Movies” era had seen Disney and Universal’s parks battle back and forth with big budget advancements in ride technology, spurring cutting edge motion simulators, mixed media experiences, and IP integration. But as tends to be the case, the innovations they’d pioneered soon rippled outward. A rising industry of ride manufacturers increasingly made brand new technology accessible to smaller, regional parks…

And one of the most ambitious adopters was Busch Entertainment – the attractions division of American brewing giant Anheuser Busch.

Though theme parks may not seem a serious domain of the company responsible for Budweiser, Bud Light, Michelob, Rolling Rock, Shock Top, and many more, the two Busch Gardens parks (in Tampa Bay, Florida and Williamsburg, Virginia) had long been part of the company’s portfolio.

Located adjacent to Anheuser-Busch breweries, the two properties (stylized as odes to Africa and Europe, respectively) had begun as humble botanical gardens meant as good will gestures to locals.

After the “post-Disney World” boom of the ’70s, both the Florida and Virginia parks began to evolve. Soon, the beautiful gardens – accentuated, respectively, by African and European dining, shopping, and horticulture – gained something new: roller coasters.

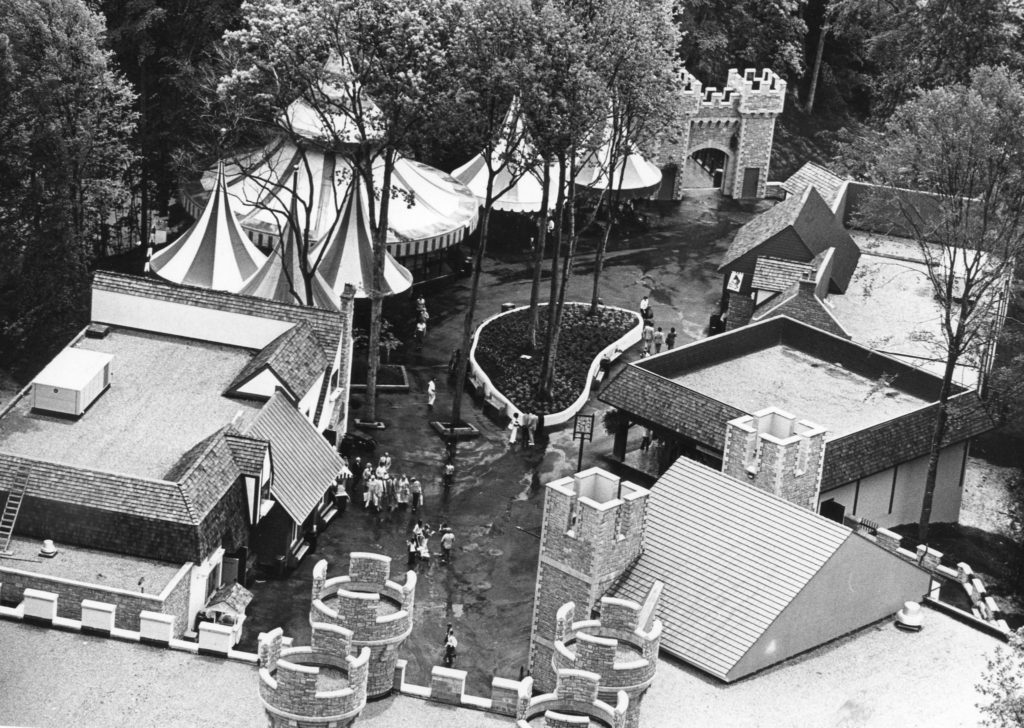

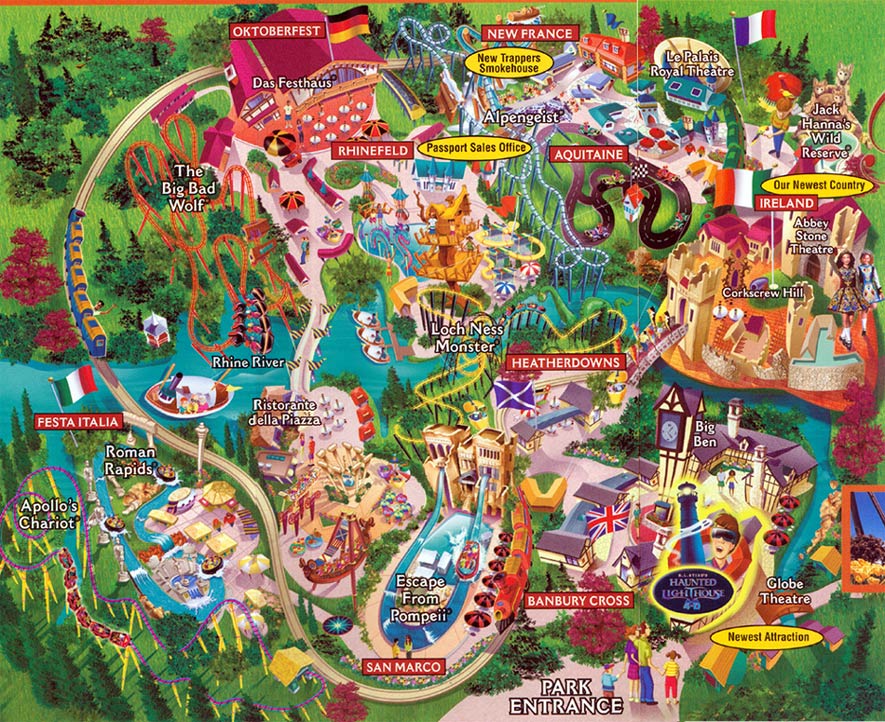

Particularly in Williamsburg, those roller coasters joined beautiful European hamlets all tucked away in the wild, forested terrain of the Tidewater region of Virginia. Its coasters were built into the terrain; they served as nods to European folklore (see, for example, Loch Ness Monster located in the park’s Scottish hamlet, right). Put another way, Busch Gardens quickly established a new “mid-tier” level in the rapidly-growing evolution of the industry; something more than a midway of amusements, but more accessible than the industry anchor in Orlando.

In 1989, Anheuser-Busch purchased the four SeaWorld Parks (in Orlando, San Antonio, San Diego, and Cleveland), giving the company a new flagship right in the middle of Central Florida’s tourism industry at its hottest moment (when Universal first came to town, ratcheting up Disney’s responsiveness and kicking off the “Ride the Movies” mindset.) Spurred by the potential to be a serious contender in the industry, Busch began to think big about what its newly-assembled collection of theme parks defined by coasters, creatures, and culture could be…

SeaWorld and Busch Gardens parks evolved spectacularly quickly in the ’90s.

On one hand, Busch was really among the first to seriously enter the “Coaster Wars” via a firmly-engrained, early partnership with Swiss coaster manufacturer Bolliger & Mabillard, whose next-generation roller coasters (renowned for their smoothness, reliability, and crowd-pleasing nature) would go on to become the industry’s standard.

And in keeping with the parks’ ethos, those coasters were always cleverly contextualized – like the B&M inverted Alpengeist (“Ghost of the Alps”) with its chalet station and ski-lift style supports, tearing through snowy chasm in a valley just outside of the park’s Bavarian Alps-themed village.

On the other hand, Busch Entertainment spent the ’90s trying some surprisingly elaborate, Disney-esque experiences in their parks. In Williamsburg, 1995’s Escape from Pompeii turned a typical shoot-the-chutes splashdown boat ride into an epic, operatic special effects show. Likewise, in 1998, SeaWorld Orlando launched the special-effects packed Declassified Disaster: Journey to Atlantis right in Disney World’s backyard, making a serious play at the kind of epic, big-budget, story-driven dark rides that only Disney and Universal had ever really tackled head-on.

Following surprisingly closely in Disney’s footsteps, SeaWorld launched a STAR TOURS-style simulators (“Mission: Bermuda Triangle” and then “Wild Arctic” at SeaWorld Parks). At Busch Gardens Williamsburg, a similar simulator opened as the steampunk fantasy adventure “Questor” (above), then became “King Arthur’s Challenge.” When a vast reimagining turned the area into a new Ireland-themed hamlet in 2001, the simulator became “Corkscrew Hill” – an adventure through Irish mythology.

But in many ways, all of that was just a test run. As a pinnacle of Busch’s ambitious race to match pace with Disney and Universal, they had something very big in the works… In 2003, the Wild Maus roller coaster located next to the Festhaus in the park’s German-themed Oktoberfest closed for good. (It was shipped south to Busch Gardens Tampa Bay, where it was rebuilt as “Cheetah Chase,” today called “Sand Serpent.”)

The relocation opened a perfect expansion pad for one of the most significant investments in Busch Gardens’ history… Behind the scenes, Busch Entertainment had assembled a crew of expert ride engineers, compute-generated graphic media artists, audio and visual projection system designers, and theming architects to develop the most elaborate attraction in the company’s parks to date…

Technology of the Future…

The first and most foundational element had to have been provided by Oceaneering Entertainment Systems – the leisure application arm of the same engineering technology supplier who’d developed the “SCOOP” ride system for its initial use in Spider-Man.

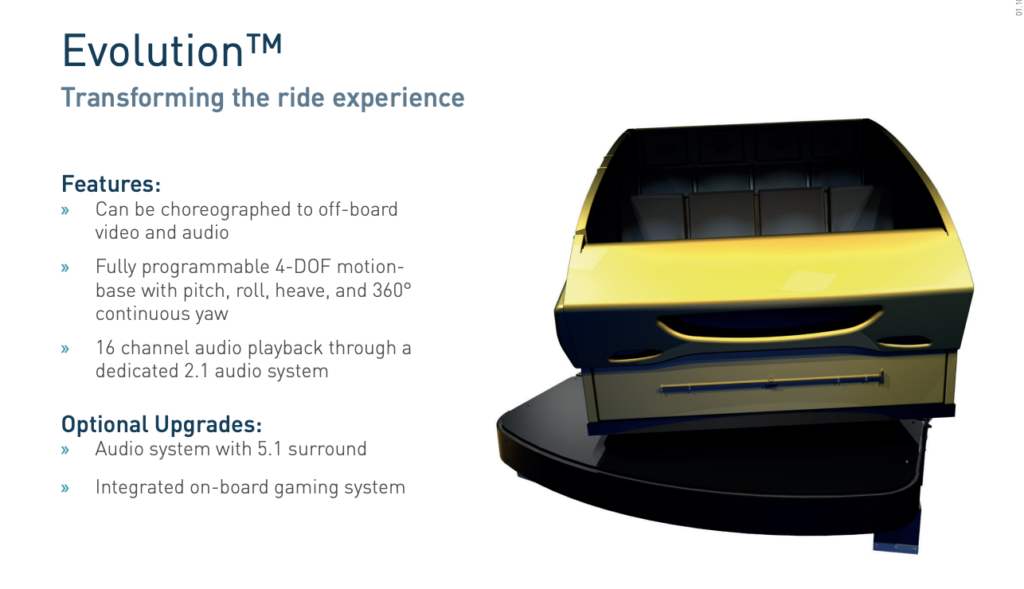

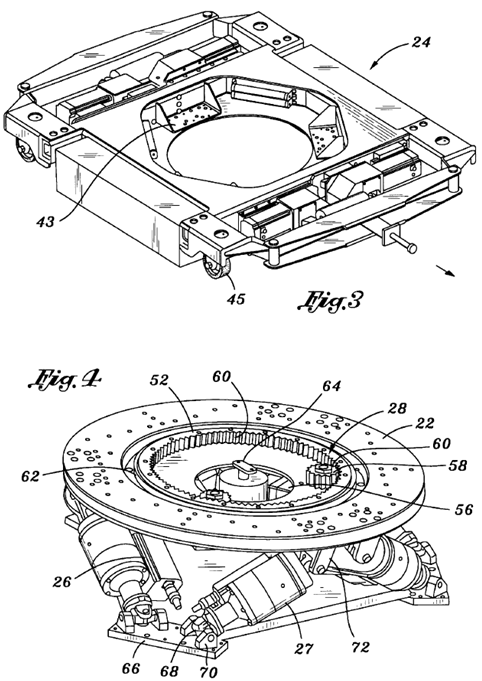

Oceaneering was no stranger to the industry (most famously, having first been called upon to use its underwater expertise to redevelop the submerged animatronics in Universal’s Lost Legend: JAWS when the original set were inoperable)… But especially after Spider-Man, you can imagine why OES doubled down, electing to enter the niche market of theme park ride technologies as a supplier. Among their first catalogue offerings was the EVOLUTION ride system – a simplified, eight-passenger “SCOOP.”

Intentionally, the OES Evolution featured just four degrees-of-freedom versus Spider-Man’s six, and used pneumatic air bags to simulate motion rather than the more costly and powerful hydraulics at Universal. It also used a pinion gear to turn 360°, allowing for full rotation and spinning.

It made sense. As the ride’s Creative Director, Cecil Magpuri recalled, “After [Spider-Man], everyone wanted a roving motion simulator. So when Busch Gardens Williamsburg looked to replace Germany’s Wild Maus with an all-new story-driven attraction, they turned to [OES]. At the time, OES had just developed a hybrid dark ride-roving motion simulator. The advancement presented affordable solutions to the elite effects parks were after…”

“…but of course, the ride system is only part of the equation. What would really make this ride a success was the marriage of story to the medium. And that’s where we came in.”

The “we” Magpuri was referring to was his company, Falcon’s Creative Group – the firm selected to take Oceaneering’s ride system and develop it into an attraction. “Oceaneering Entertainment Systems sought us out really looking not only storytellers, but a vendor who would consider park, ride, and story demands and then deliver.”

In other words, Falcon’s needed to work within the pre-determined “SCOOP” ride system and its placement in the park’s Germany, backwards engineering a family dark ride to fit the park’s brief – a thrilling, show-stopping, 21st century haunted house. Falcon’s would be responsible for developing both the ride’s narrative elements (like story, characters, and setting) and its operational elements (like layout, software, and motion profile).

Then, the work of engineers at Oceaneering, animators at Super 78 Studio, scenic designers and installers at Nassal, and audio/visual suppliers from Electrosonic would all need to come together into a cohesive project… on the limited scale of time and money necessitated by a seasonal park’s operating schedule and budget. There was no room for error with this project – one that would put Busch Gardens Williamsburg on the map.

But none of the work could really begun until designers had a story to work with…

… and a Legend from the Past

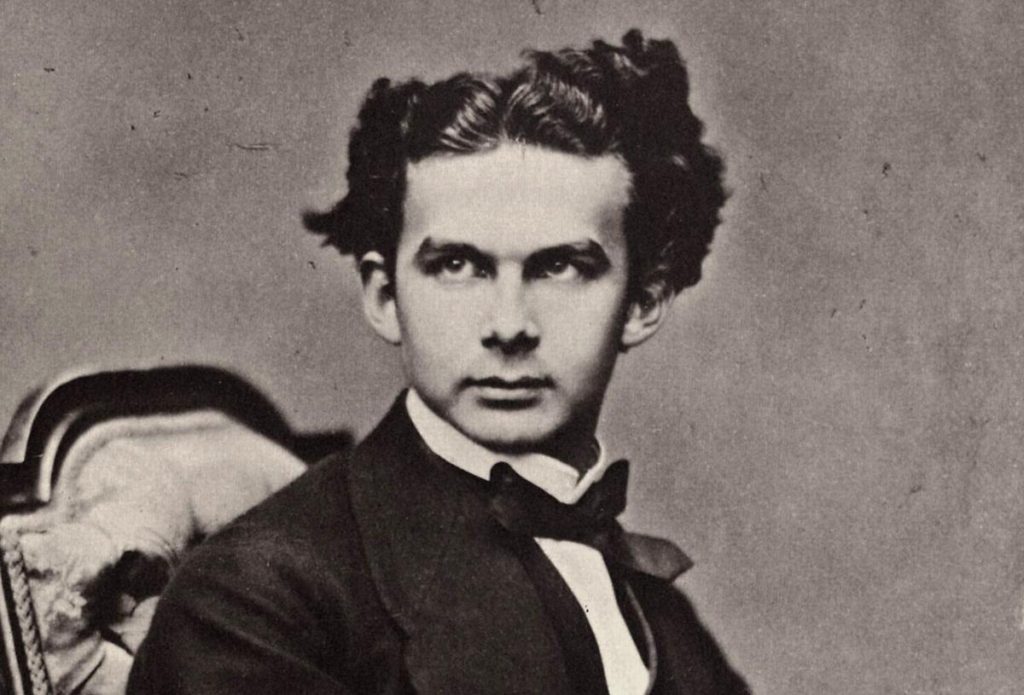

King Ludwig II of Bavaria (sometimes called Der Märchenkönig – the Fairy Tale King) was indeed an unusual – but very real – historical figure. After a deadly three-day illness killed his father, Ludwig ascended to the throne in 1864 at only eighteen years old. Disinterested in the role and ill prepared to be King (as most teenagers would be), Ludwig was nonetheless popular among the people for his youth… and his brooding good looks.

Consequently, he made little effort to reform policy or precedent, avoiding social gatherings and public speaking altogether. Instead, Ludwig kept to himself, concealed in his palace as he contemplated fine arts, music, and architecture. His mother even noted that she feared for her son, given his “insurmountable shyness.”

While the reclusive king’s popularity soared with the people, Ludwig’s eccentricities created great tension in his government… Especially when he hoarded personal funds to finance pet projects, like the lavish Neuschwanstein castle (famously, the architectural inspiration for Disneyland’s Sleeping Beauty Castle), bankrupting the Kingdom. Still, Ludwig continued ahead with still more lavish projects, seeking loans from European royalty.

When Ludwig’s ministers got wind of Ludwig’s plan to dismiss them, they acted quickly to remove the king from the throne.

Lest Ludwig successfully remove his counselors and spend Bavaria into ruin, his advisors sought to have the young King declared mentally incompetent, with only his excessive spending and his ostentatious tastes as evidence. They succeeded. Ludwig was declared “hopelessly insane,” earning the nickname “Mad Ludwig” that has followed him through history.

The day after his deposition and the removal of his crown, Ludwig was found floating in a pond on the castle grounds, dead… though his death was ruled an act of suicide by drowning, no water was found in his lungs. He was only 40 years old…

Ludwig himself is believed to have told those in his inner circle, “I wish to remain an eternal enigma to myself and to others.” Fittingly, the story of “Mad Ludwig” has been passed down through time and – like all great legends – grown.

And for Busch Gardens Williamsburg, it served as just the original story needed for a 21st century adventure…

Reading this brings back so many memories. Curse of Darkastle was such a unique and special ride. It’s inclusion of a unique story, beautiful scenic work inside and out, and use of an emerging ride system tailor-made for lower budget, regional parks was such a huge step forward for the industry as a whole. Were it not for A-B needing to sell the entertainment division during its merger with InBev, immediately followed by the Great Recession, I truly feel we would see more of this ride system and a lot of creative and beloved experiences at many of the regional chains. Its decline is truly sad. In a park that is so consistently the most beautiful park in the country, the slow demise of DarKastle should have been the canary in the coal mine for BGW fans. Since this, we have seen quality decline around the park. I’m not intending to imply that the park is in shambles, but the unthemed Pantheon and lack of scenic elements and effects in DarKoster shows that budgetary considerations are the main priority. The spirit of creativity, and the willingness to take chances that could pay off for a singular park as well as the industry is slowly eroding at every park. However, seeing Cedar Fair beginning to invest again in themed lands (Aeronautica Landing at Carowinds and The Boardwalk and Cedar Point) gives me hope that we are at the beginning of a rebirth of regional parks outside of simply thrill destinations, and I hope that BGW joins in the revolution. The tradition and history of that passion exists in the forest in Williamsburg, and starting small with improvements and unique storytelling like DarKoaster is a first step back to what we all remember.