Westcot rises…

They say that the sequel is never quite as good as the original. So imagine the pressure placed on Disney Imagineers tasked with designing the follow-up park to act as an equal partner and companion of the most beloved theme park on Earth… all while capturing in one fell swoop the same globally-recognized destination status as Walt Disney World.

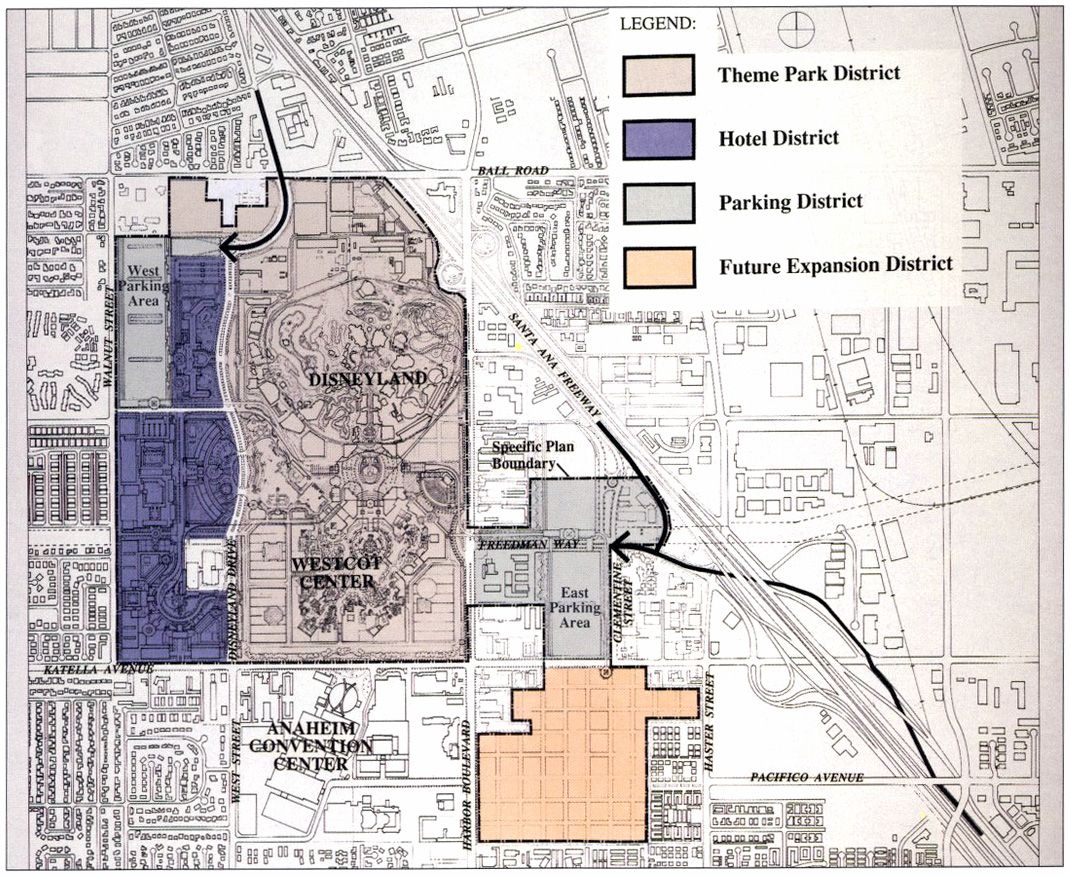

When the new Disneyland Resort was officially announced on May 8, 1991, the anchor of the plans was to be WestCOT Center.

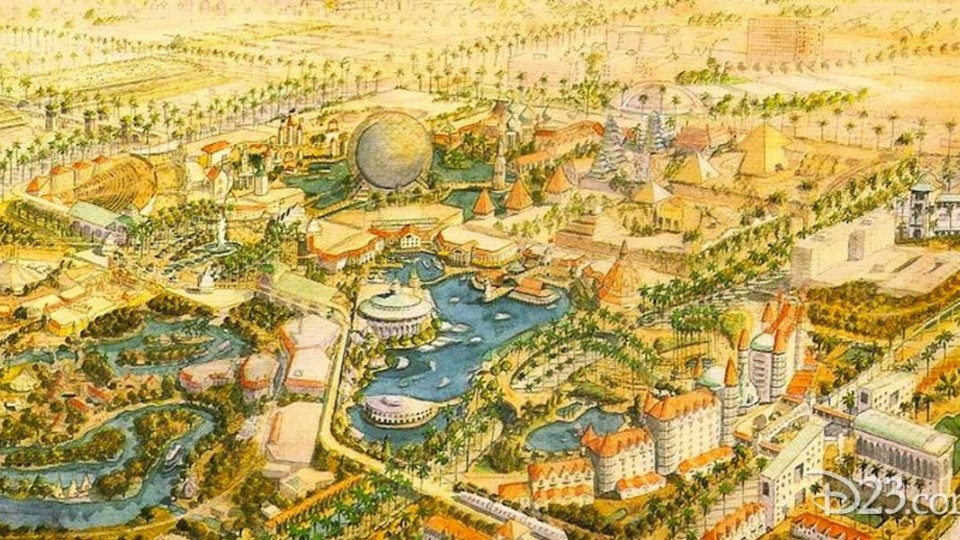

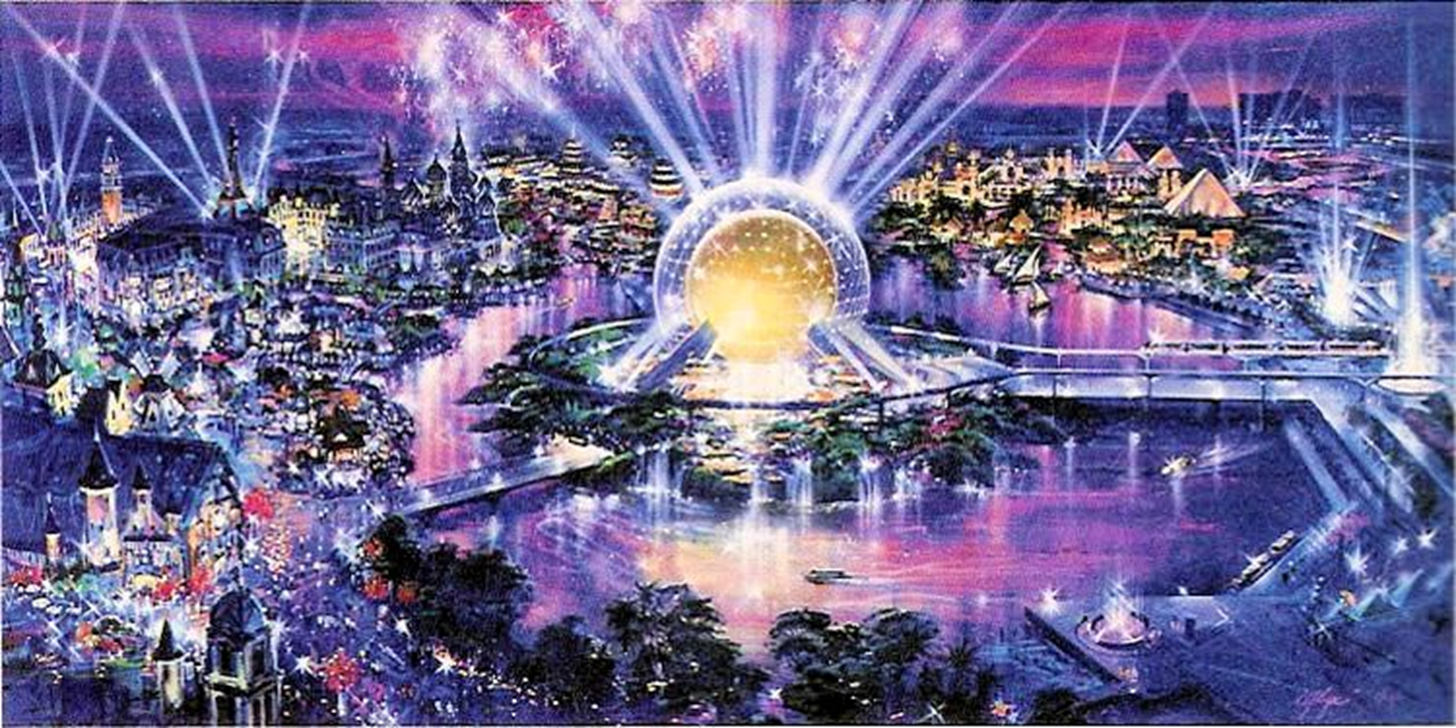

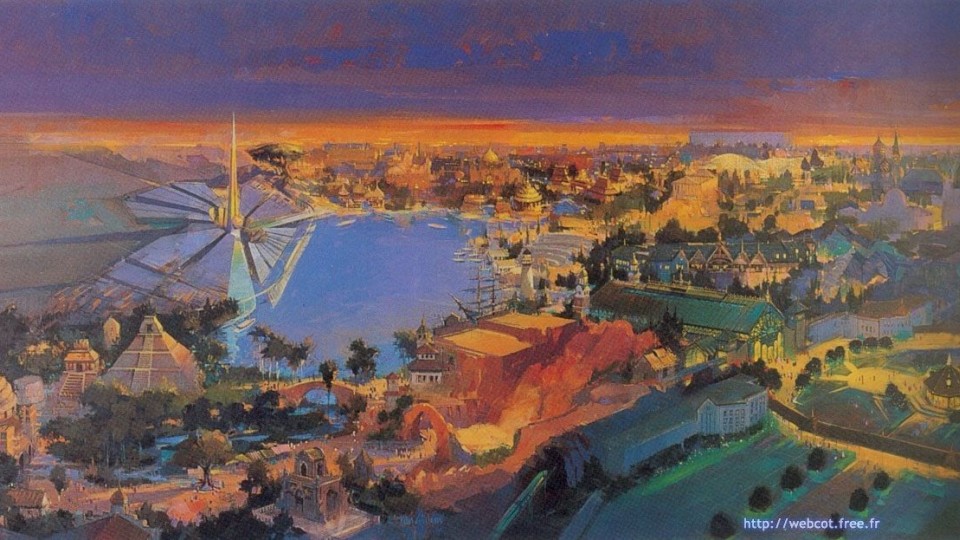

Despite its name, Westcot would differ dramatically from its Floridian sister which – even a decade into its life – was already in the midst of the first waves of reinvention. Learning from Epcot’s flaws and adapting to a Southern Californian style, Westcot would replace concrete plazas, geometric planters, and monumental ’80s architecture with lush, warm gardens, waterfalls and rockwork, and the golden Spacestation Earth to reign over it all.

Westcot would also reorganize the EPCOT model, combining the separate pavilions of Florida’s World Showcase into a more unified “Four Corners of the Globe,” with guests walking through the history of civilization from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to Colonial America (and then, for Park Hoppers, onward to Main Street, U.S.A.). Future World, meanwhile, would be rearranged into The Wonders of Life, the Wonders of Space, and the Wonders of Earth. Altogether, these seven pavilions would be the “Seven Wonders of Westcot” creating one of Disney’s most interesting reinventions ever and a new counterpart to Disneyland.

The massive Disneyland Resort expansion (including Westcot) was to break ground in 1993, assuring a fully operational system by 1999. Before the New Millennium, PeopleMovers, Monorails, and shuttles would be connecting the various elements of the Disneyland Resort and its two theme parks.

But the problems began before a single shovel of dirt had shifted.

…and falls

Ultimately, Westcot ran up against an immovable force: Anaheim homeowners. Residents of the largely conservative upper class suburb of Anaheim rallied against Disney’s expansion, objecting to the eminent domain land grabs, public infrastructure dollars, and years of construction that would’ve been required. And worse, the end result would see a 300 foot golden sphere looming over their proverbial and literal backyards.

In so many words, Walt’s disdain for the real world that had surrounded his park came full circle when the real world decided to fight back.

Disney redrew plans for Westcot to respond to the public’s criticism, replacing Spacestation Earth with a towering white spire far less intrusive to neighborhood views. They argued that residents would never see the increased traffic since dedicated highway ramps would funnel visitors directly into the parking decks, and that Disney needed the $395 million it requested from the government to help build them, which only incensed the locals further. All the while, Michael Eisner watched the price tag for the project inflate.

By the end of its concepting, Westcot’s anticipated cost was reportedly nearing $4 billion. If you’re interested in the immensely-scaled, massively-ambitious, never-built second gate Disneyland almost got, you can dive into the full story of this alternate reality version of the Disneyland Resort in its own Possibilityland: WESTCOT Center feature.

1994

Disney’s initial plans had called for Westcot to be well into construction by the start of 1994. But no earth had yet moved. Instead, fighting for the embattled second gate in Anaheim was among the least of Disney’s worries.

The first was surely Disneyland Paris. Opened in 1992, Disney’s first European theme park had been widely derided by the French press even before its opening. Despite being lovingly rethought for European audiences and decked out in more luxury and expense than any Disney Park before, the resort had never found its financial footing. Overbuilt with far too many hotel rooms, the Paris project – meant to be Eisner’s landmark and legacy on the company’s history – was instead an embarrassing boondoggle.

Two years into the park’s operation, the Euro Disney S.C.A. subsidiary was reportedly burdened with over $3 billion in debt – an unconquerable sum. In March 1994, Eisner announced that Euro Disney declaring bankruptcy was on the table. If it had happened, that would’ve meant that Disney would effectively abandon the resort entirely. It was a bold move and a political gamble meant to force European banks to cut interest payments and delay debt collection. It worked, but just barely.

Justifiably skittish about green-lighting such an elaborate project, Eisner transparently told the LA Times, “We had a very big investment in Europe, and it’s difficult to deal with. I don’t know whether a private company can ever spend this kind of money.”

To make matters worse, in April 1994, Frank Wells – Disney’s President who’d arrived at the company with Eisner a decade earlier – died in a helicopter crash. Widely regarded as the financially-minded “Roy” to Eisner’s creatively-oriented “Walt,” Wells’ death seemed to have a profound, destabilizing impact on Eisner, who (no doubt petrified by the Paris debacle) surrounded himself in financially-minded, “penny-pinching” executives for the remainder of his tenure with Disney.

One of them was Paul Pressler (left), who stepped in as the President of Disneyland in November 1994. Arriving from Kenner Toys, Pressler’s penchant for merchandising and cost-cutting pretty quickly put him at odds with Marty Sklar – head of Imagineering. Notorious among the team (and later, guests), Pressler immediately set to work slashing budgets, making enemies, and installing his own loyalists whose focus on operational optimization would lead to Disneyland’s darkest periods ever.

Suffice it to say that by early 1995, it was official: Westcot was dead. The never-built second-gate and its $4 billion price tag were an unthinkable expense for a division of the company that had shifted from a creatively-oriented mindset to a revenue-maximizing one. Any hopes for an ultra-ambitious Disneyland Resort anchored by an industry-changing new theme park were off the table… But the mandate that Disneyland play host to a second theme park was not.

The drawing board

On August 2, 1995, Eisner took a few dozen executives and designers from the Walt Disney Company on a three-day retreat in Aspen, Colorado. Eisner knew that the team needed to re-group. They’d lost countless projects to the near-miss in Paris, and they needed an action plan.

Paul Pressler himself recalled in Leslie Iwerks’ The Imagineering Story that “Michael and I assembled the Imagineers” and presented them with a mandate: that post-Westcot, Disneyland needed a second gate that was “scaled back to a level that the company felt we could move forward prudently and make money. “

Imagineers were split into small groups, each tasked with coming up with a plan for Disneyland to adopt Walt Disney World’s “multi-day, multi-park resort” strategy. The difference now was that whatever they dreamed up had to cost very little.

And as any Disney Parks aficionado will tell you, those executives faced an incredibly difficult task. Walt Disney World’s purpose – its very reason for being – was as a self-contained “Vacation Kingdom;” a destination the world over. It’s fair to imagine that most people arriving at the Orlando International Airport since 1971 have had Disney World somewhere on their itinerary… usually, the primary destination!

Though competitors big and small had sprung up, their wildest aspirations were to borrow Disney’s customers for a day or two. And to that point, Disney made intentional moves throughout the ’90s to ensure that their “walled garden” remained guests’ only stop – like the Magical Express (stay here and you don’t need to rent a car!), the Disney Dining Plan (eat here and food is free!), and even FastPass (play here and you won’t wait!).

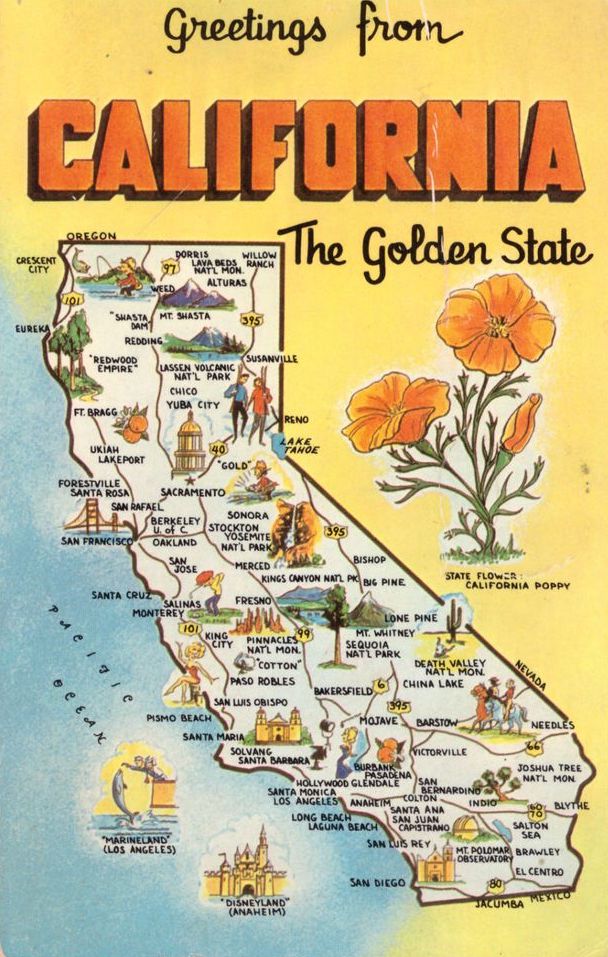

But Disneyland is not Disney World. And more to the point, California is not Florida. From its 1955 opening to the mid-’90s, most visitors to Disneyland came from within 100 miles of the park (which is why Disney historian Jim Hill calls Disneyland “the world’s most popular regional theme park”). The park’s heavily local (and heavily vocal) audience was mostly made of multi-generational families who’d passed Disneyland down like an heirloom. For Disneyland to become a destination for visitors from around the country and globe, it needed more than just a second theme park; it needed to compete with… well… the rest of California. Beaches! Redwood forests! Hollywood studios! Lush mountains! Verdant valleys! Beautiful deserts! Coastal highways! San Francisco! How could Disney’s designers possibly convince guests to stay multiple days at the suburban Disneyland Resort when the rest of the Golden State was calling?

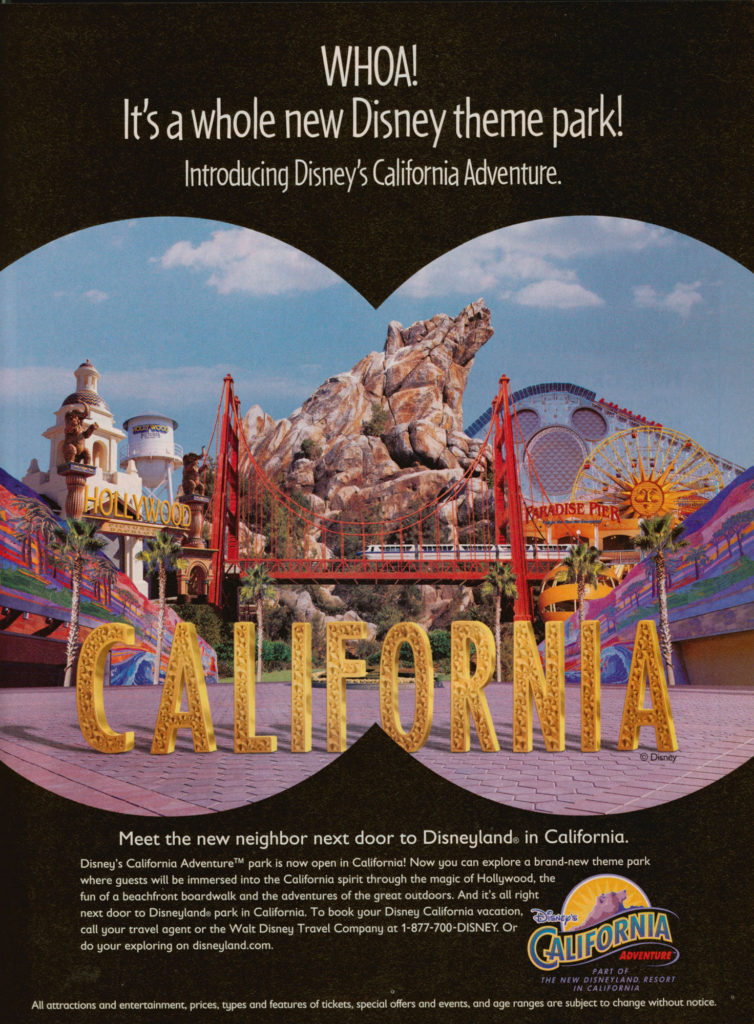

Eureka! Imagineer Barry Braverman recalled in The Imagineering Story, “I was not the only one, but I did pitch the idea of a park themed around California, because I thought that would be a cool thing to do. I figured the California theme – with Hollywood and the beach and the farming and the great wilderness of the High Sierras – would give us a lot to work with, a lot of places to put things. Because we knew we weren’t going to be able to invent every ride out of whole cloth.”

Braverman suggested that the park could be a celebration of “the Californian dream, manifested in the dream of Hollywood, of stardom; of the dream that’s represented by the beach and surfing and all of that; the dream of flight, of aviation; the dream of agricultural bounty. All of these things that became areas and lands of the park were embodiments of the California dream. And that gave us a lot of leeway.”

Using a word often tossed around in thematic circles today in a very different sense, Pressler told Leslie Iwerks “What we wanted to do with California Adventure was [….] we wanted to make it more immersive. A little bit more like EPCOT in innovations where it wasn’t just about riding rides. It was about immersing yourself in the lifestyle and the culture, particularly around the workplace and a lot of the history.”

What that meant, of course, is that the new park would be more focused on retail, drinking, and dining than on rides. To that end, Pressler employed his team from merchandising and retail sectors to design much of California Adventure, positioning dining and shopping as the highlight of the more “mature” park; where sponsorships from Mission Tortilla, Robert Mondavi Wines, Boudin Bakery, Wolfgang Puck, and other upscale sponsors could underwrite and operate their own restaurants and attractions, serving as tenants – actually, a model used by Disneyland back in its earliest days.

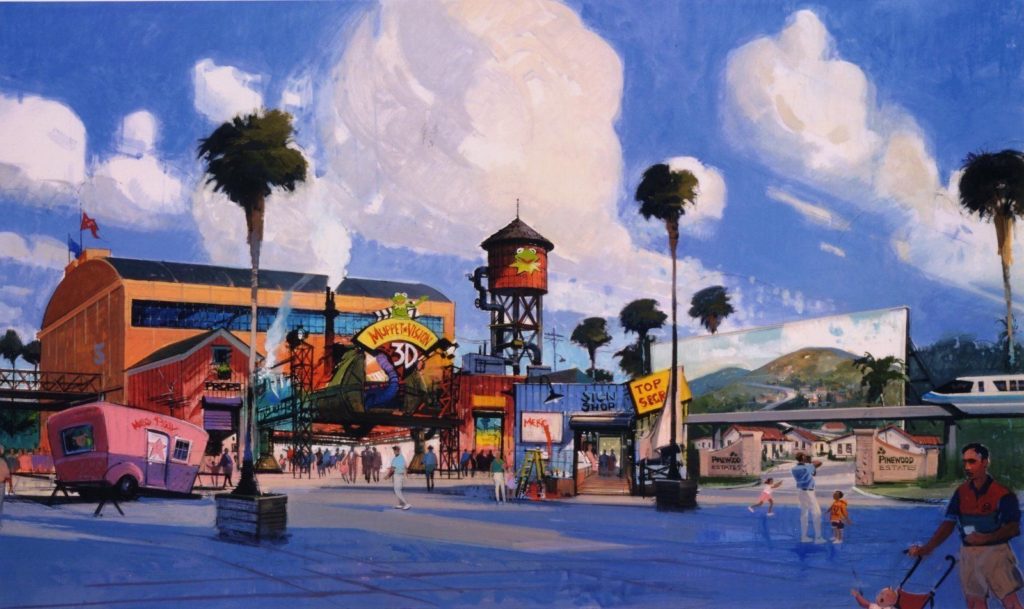

At the same time, an Imagineering team was quickly assembled under Marty Sklar to begin to ideate on a Californian theme park – primarily, which attractions already developed for Walt Disney World could be quickly and effectively duplicated to fill park areas based around the “dreams” Braverman posed. Eisner reportedly loved the park’s proposed layout, and how attractions like “Muppet Vision 3D” and “It’s Tough to be a Bug” could fit the park’s brief without new research and development dollars, playing as “new” to Californian audiences.

At Imagineering, there was a clear divide between the teams working on California Adventure and the other park WDI was involved with at the time: Tokyo DisneySea. “There were a lot of people at that time that had a difficult time going to lunch together,” Marty Sklar told Iwerks. And that divide would become increasingly wide…

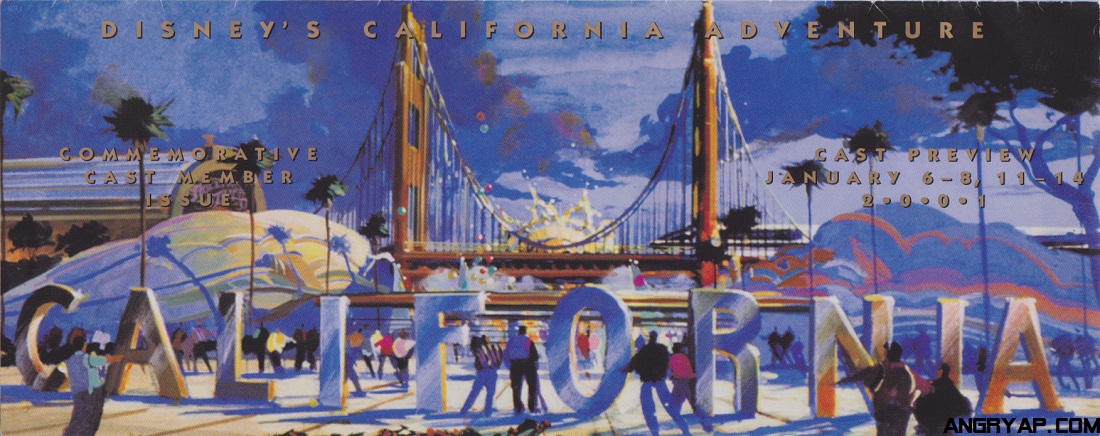

Pre-Opening

On January 21, 1998, the parking lot at the entrance to Disneyland closed. The next morning, construction started on Disney’s California Adventure. The 55-acre theme park would stand where the parking lot once had – the only large, open land that the California resort had to spare. Of course, even preparing the space for the park was a substantial task given that the parking lot needed excavated, and infrastructure like plumbing, electricity, and artificial waterways had to be dug out and installed.

At the same time, a massive undertaking saw the area around the expanding Disneyland rezoned as the Anaheim Resort District, beginning a public-private joint effort to tame the wilderness of Harbor and Katella with unified design standards, signage, landscaping, and purposeful pedestrian access – one of the most far-reaching effects of the Disneyland Resort expansion effort.

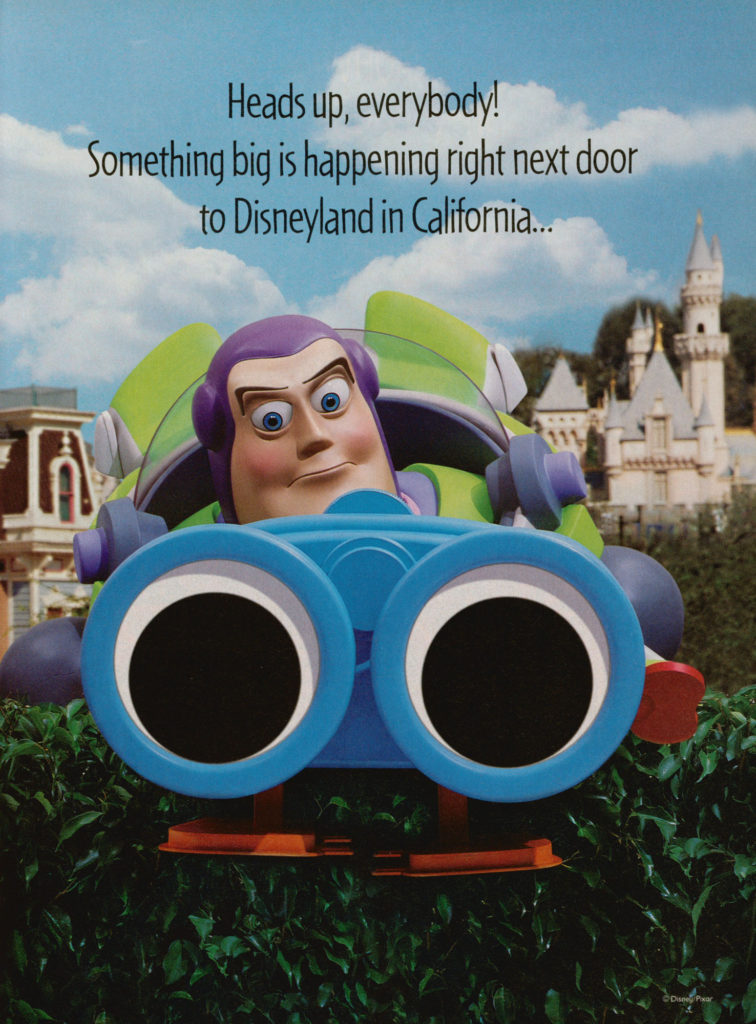

That October, a Preview Center opened on Main Street, U.S.A., providing guests with a sneak peek at the 22 “shows and attractions” and 15 restaurants planned for Disney’s California Adventure.

Altogether, the new park, an attached deluxe hotel, and the Downtown Disney shopping district would cost $1.4 billion – less than half of the much grander, Westcot-anchored expansion that had been cancelled three years earlier. Of that price, Disney’s California Adventure itself would only take an estimated $650 million of that. (For reference, Tokyo DisneySea – which opened just seven months later reportedly cost $3 billion alone… nearly five times as much.)

Image: Disney, via @ArchivistJason (Twitter)

Annual Passholders got exclusive access to the park before its official opening in February 2001, and the early reports they sent home were… well… Uh oh.

On the next page, we’ll step into the Disney’s California Adventure Park of yesterday and experience its four districts, addressing the worries that Disney Parks fans so rightly expressed as they experienced the second gate at Disneyland.