Imagined

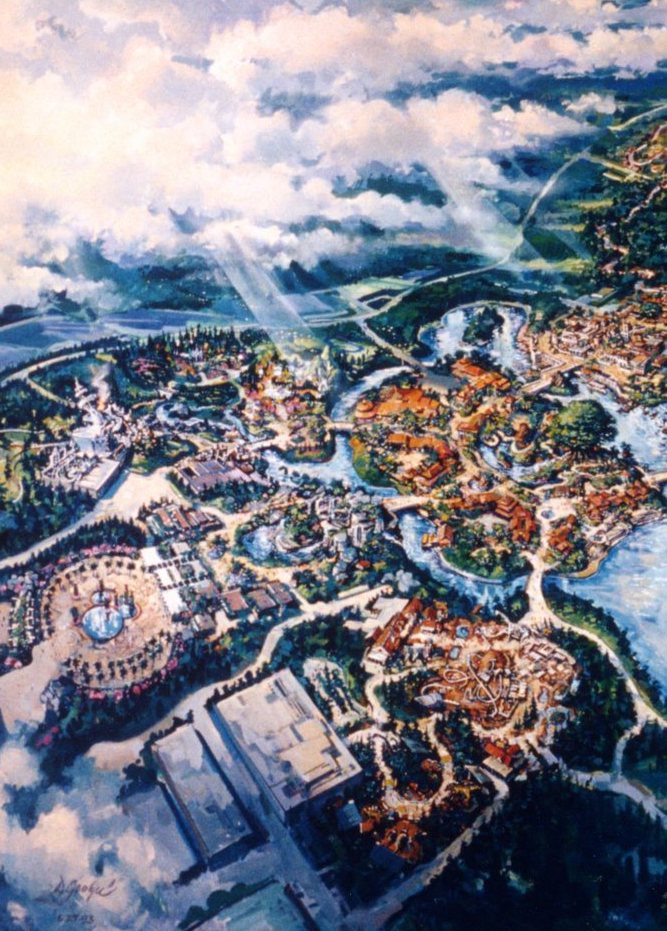

At the height of Animal Kingdom’s concept and development, the park would’ve opened with no less than seven headlining attractions – Kilimanjaro Safaris in Africa, three attractions in Beastly Kingdom, Asia’s Kali River Rapids, and Dinoland’s safari and Excavator. But the ‘90s were a tough time at the Walt Disney Company thanks, in large part, to the failure of Disneyland Paris. The infamously overbuilt project sidelined or downsized nearly every major project in the works at the time. All the while, Animal Kingdom’s projected price tag was growing.

Of course, as the popular story goes it came down to funding either Beastly Kingdom or Dinoland for opening alongside the park in 1998. Executives opted for the latter. Why?

- 1993’s Jurassic Park had elevated dinosaurs as never before in the public consciousness. Overnight, dinosaurs were not only a pop culture boon to Disney’s newest theme park, but an opportunity for evergreen merchandising;

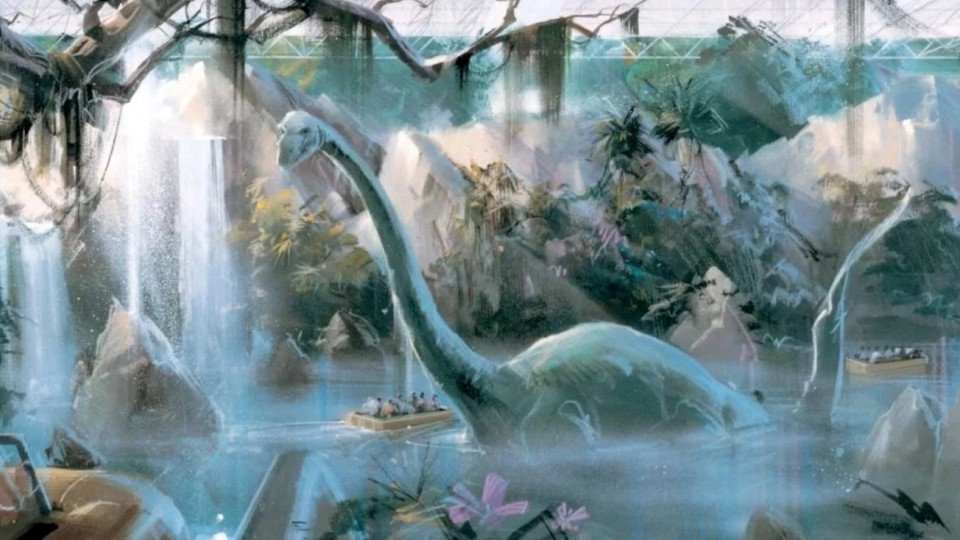

- Just a few miles away, Universal was breaking ground on its own new theme park, and while Islands of Adventure itself was a looming threat to Disney’s dominance, the new park’s centerpiece would be an entire Jurassic Park-themed land with the Modern Marvel: Jurassic Park River Adventure as its centerpiece;

- Disney was working on its own film – an Eisner pet project called Dinosaur – that would debut just a few years after Animal Kingdom, with spectacular opportunities for synergy;

- According to the Disney Dish Podcast, Imagineers working on the Dinoland project had made a case for combining Dinoland’s two planned attractions – the thrilling Excavator and the placid safari through a prehistoric jungle – by using the technology and ride layout developed for Disneyland’s Modern Marvel: Indiana Jones Adventure, thus presenting a cost-savings for Dinoland over Beastly Kingdom’s much grander scale and three attractions.

Unsurprisingly, the newly-rearranged and cost-conscious Dinoland won out. Maybe that in itself tainted Disney Parks fans’ attitudes toward Dinoland… But you might be surprised what guests found there when they entered the park in 1998…

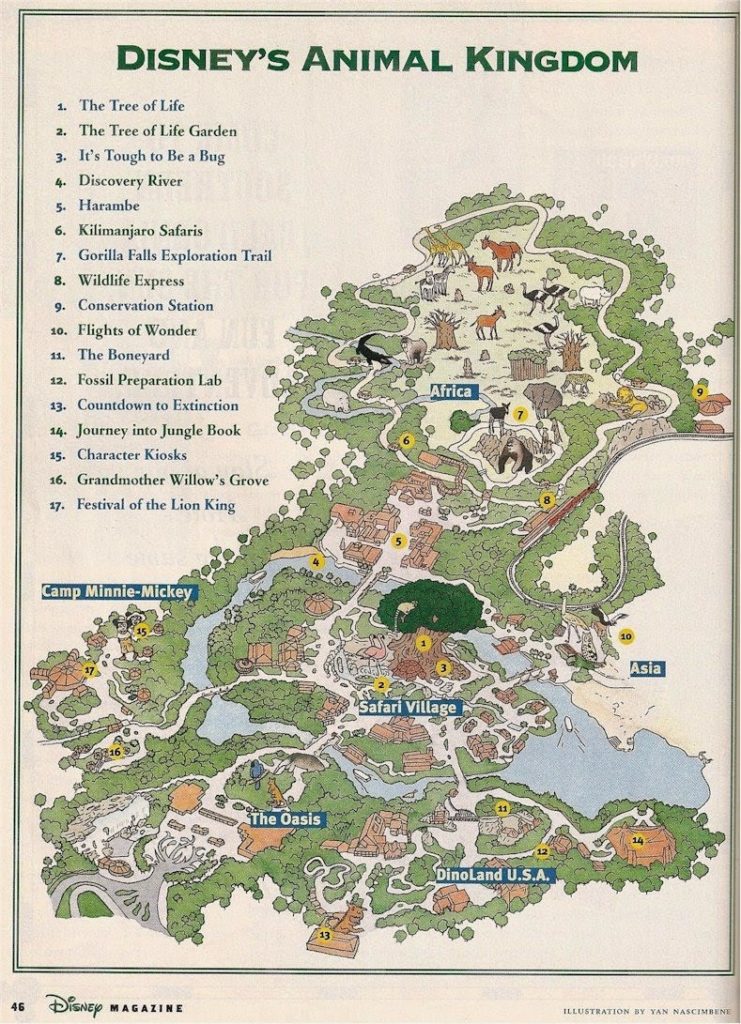

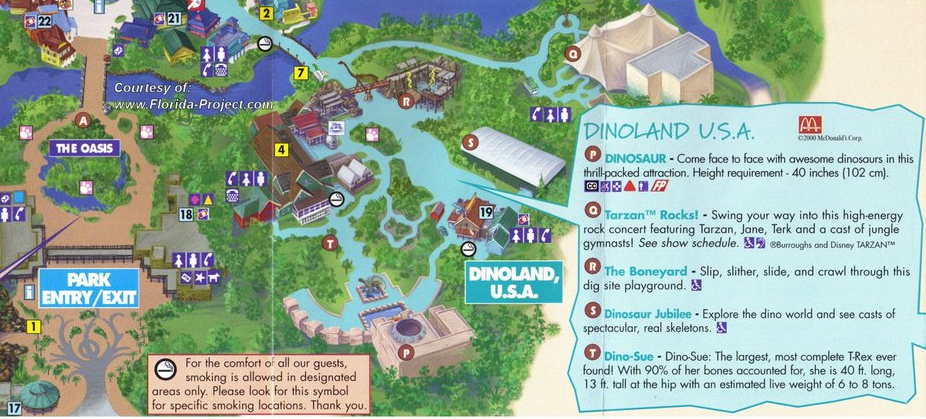

Dinoland, U.S.A.

Would Disney’s Dinoland transport guests to the ancient past? Of course not. (First of all, that’s a pretty logistical impossibility given the realities of a theme park. Restrooms? Restaurants? Employees?) And bringing dinosaurs to our world might ring a little too close to Jurassic Park (and Universal’s clone of the Lost Legend: Jurassic Park – The Ride under construction up the road).

Nope. Dinoland would be incarnate as a place rooted in reality; a fictional – but not fantastical – world where we, as guests, might step into a story to be transformed by adventure. As told by Melody Malmberg’s The Making of Disney’s Animal Kingdom, the opening day Dinoland had a story as rich as Harambe’s or Anadapur’s. The only difference from its globe-trotting counterparts is that this story was not quite so far from home…

In fact, Dinoland is set in a quiet town in Diggs County somewhere between Texas and the East Coast of the Southern U.S. (in-park evidence shows, perhaps even in Florida’s panhandle…) along U.S. Highway 498 (get it?).

The idea’s simple: we’re tourists who’ve stumbled upon a town built by dinosaurs. Not literally, of course… But back in the 1940s, this quiet unincorporated territory within Diggs County was little more than a paltry gas station built by a couple on their own farmland; a sleepy, silent spot for refueling, perfectly positioned at the dawn of the “road trip” era. We can imagine, for example, that families in sedans might’ve stopped in Diggs County en route to newly-opened Roadside Wonders: Weeki Wachee Springs or Gatorland; “tourist traps” blooming along U.S. highways leading to Florida’s sun-bleached beaches.

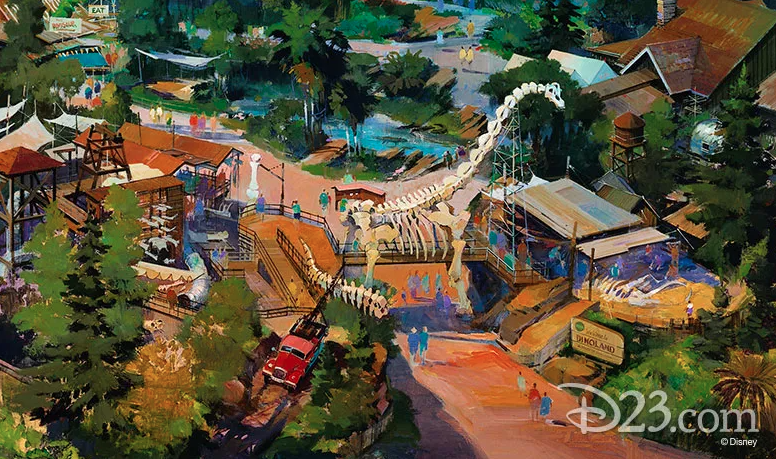

Everything would change in 1947, when amateur fossil hunters would strike the motherlode of dinosaur remains in Diggs County. (Note the irony of fossils being discovered near a Sinclair gas station, whose iconic dinosaur logo reminds us that gas is derived from fossil fuels…) By the 1950s, paleontological grad students flooded to Diggs County to unearth a treasure trove of fossil remains, overtaking an old fishing lodge nearby to establish “The Dino Institute.”

By the ‘70s, the Dino Institute had grown in prestige, earning the construction of a real, purpose-built museum and research facility showcasing some of the local finds in classic paleontological exhibitions. Enter Dr. Helen Marsh, the newly-appointed president of the Dino Institute who, in the ’90s, oversaw the acquisition of Chrono-Tech, a scientific start-up researching time travel… a potential future for dino-study…

But nevermind that sci-fi pipe-dream. The narrative of the land begins now, with our arrival. As expertly evidenced by Jack Spence of AllEars.net, when we step into Diggs County, it’s at the crossroads of three competing visions by its three primary inhabitants:

- The academics; the Dino Institute’s scholarly researchers, holed up behind the ’70s white concrete exterior of the Dino Institute, who study the realities of prehistory and carefully arrange hands-off exhibitions to pass knowledge of the prehistoric world on to us.

- The grad students; the modern class of paleontology students for whom Diggs County has become an adopted home and college party town. Evidence of their playful nature can be seen around the land (particularly in affixing the “-osaurus” suffix to anything in sight, leaving their lawn chairs and coolers on rooftops, and commandeering the land’s radio broadcast with songs such as “It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” by R.E.M. and “Godzilla” by Blue Oyster Cult).

- The locals. For example, that gas station – around since the ’40s – is still here! Its proprietors – a now-elderly Chester and Hester – have clearly bought into the dino-frenzy, spending the last few decades converting their old farmland and gas station into a roadside delight… much to the chagrin of the academics, who balk at their scholarly subjects being hocked as a tourist trap.

In 1999, it was Chester and Hester’s Dinosaur Treasures that initially told the story of the locals – a folksy, gaudy, and intentionally-obnoxious store affixed with decades of signage and outrageously crafted dinosaur sculptures meant to lure roadtripping families off the highway. In fact, the concrete dinosaur in front of Chester and Hester’s was designed by prominent folk artist Gregory Warmack (who went by Mr. Imagination), who was in Orlando to work on Downtown Disney’s House of Blues.

In our Special Feature tour of Animal Kingdom through Joe Rohde’s own words, the park’s lead creative commented, “I believe that the work he created for us is not actually included in his curriculum vitae. It should be. […] I think it’s kind of interesting that our tribute to the unsung folk arts of America includes an actual work of unsung Folk art.”

In any case, Chester & Hester’s folksy ode to ancient reptiles was a harbinger of things to come… Rubber tire planters, rusted gas pumps, old service station garage doors, and cartoon dinosaurs spoke to the “locals'” appropriation of dinosaurs. But the real needs of the larger Animal Kingdom meant that this folky souvenir shop would soon serve as the central building-out point for an entirely new mythology and mini-land…

Band-Aids

Remember how the dreamy, Blue Sky concept of Disney’s Animal Kingdom would’ve brought seven headlining attractions to the park? It opened with just two – the starring Kilimanjaro Safaris and the terrifying Countdown to Extinction. And though guests could spend days exploring the park’s hidden corners, uncovering the built-in histories of its themed lands, discovering the park’s stellar shows, and – lest we forget – encounter animals, not everyone had such a thoughtful evaluation of its offerings.

Animal Kingdom was quickly labeled as beautiful, but only worthy of a half-day visit. What’s worse, families reported that there was practically nothing for their kids to enjoy beyond Dinoland’s Digsite. Animal Kingdom needed a fast influx of family attractions to both break from the park’s ultra-serious messaging and to add capacity in the massive park with so few rides. There were no family dark rides at all; very few Disney characters could exist in such photorealistic lands; Fantasyland flat rides would stand out like a sore thumb in most of the park… Except…

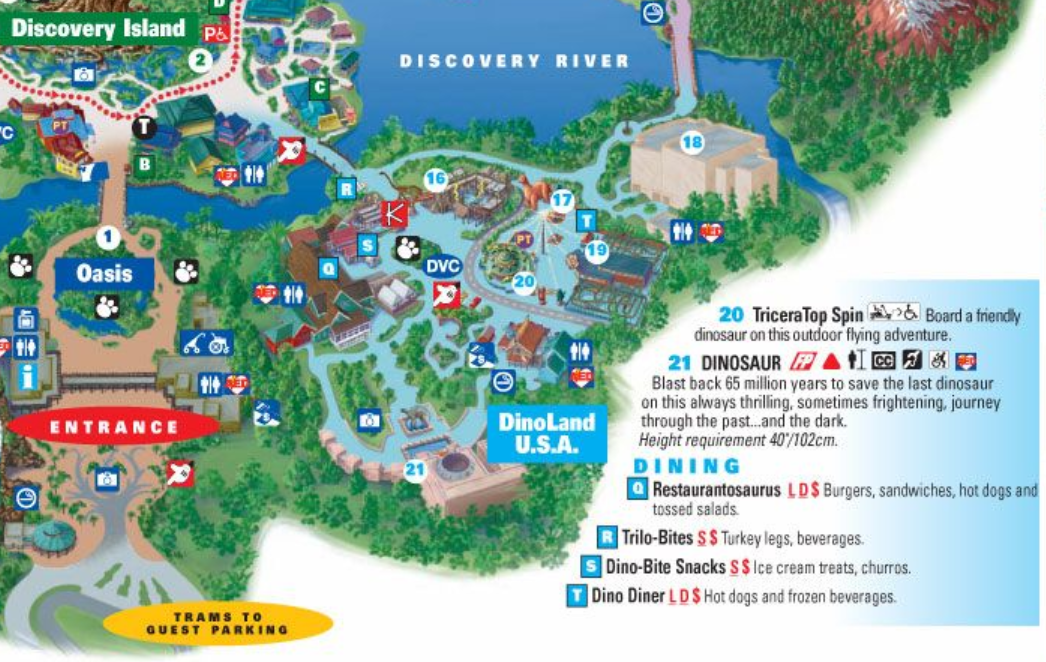

In 2002, an expansion overtook the former Dinosaur Jubilee tented exhibit area inside Dinoland. That (admittedly, temporary) tent staffed by humorous “Dino Institute” students and filled with their findings was torn down, and in its place Disney created… an old, cracked asphalt blacktop parking lot. No, really…

Chester & Hester’s Dino-Rama

Entering Dinoland, U.S.A. now, something significant has changed. Half of the land has… well… evolved. Just off of the striped highway that now slices its way through the land, the saturated colors of Chester & Hester’s Dino-Rama take center stage. Atop faded parking space lines and cracked blacktop asphalt faded in the Florida sun, a comic-book carnival of dayglo dinosaurs had unfolded like a pop-up book, dominating the roadway.

If you think that this cartoonish carnival looks like the kind of thing you’d expect from a roadside attraction rather than a Disney Park, you’re right.

The mini-land is lorded over by the massive, smiling “cementosaurus” that acts as a gateway from the park’s Asia, strung up with popcorn lights and looming over carnival games like “Whack-a-Packycepholosaur,” “Mammoth Marathon,” and “Bronto-Score.” In its center stands the TriceraTop Spin, a pastel-painted, triceratop-encircled aerial carousel akin to Dumbo the Flying Elephant, here guarded by multi-colored fair fencing and a ramshackle queue covering that looks of it was handbuilt.

The land’s highlight, though, is the Primeval Whirl, a spinning “wild mouse” roller coaster ostensibly poking fun at the goings-on at the nearby Dino Institute. The off-the-shelf carnival coaster is adorned with spinning props and cartoon-stylized “scientists” depicted in the station as it clatters and shuffles through its lattice work of bare, exposed steel.

For most guests, what they see in Dino-Rama is a loud, obnoxious zone that dispenses with Animal Kingdom’s thoughtful style in favor of the swirling TriceraTop Spin (its name a spoof of the “top spin” carnival ride) and the comic-book-stylized Primeval Whirl, a spinning “wild mouse” coaster through cut-out set pieces and props made by the French manufacturer Reverchon.

But can that really be all their is to this 2002 addition to Disney’s Animal Kingdom? Did Imagineers suddenly forget everything they knew when they designed the park? Can it be that Disney simply set lazily-themed carnival rides in the middle of the park for no reason? Of course not. On the page page, we’ll set out our (half-hearted) defense for Dino-Rama and explore the details deeply embedded in the land that tell a story almost no one knows…

Ready to dissect that frog? Read on…