Popular

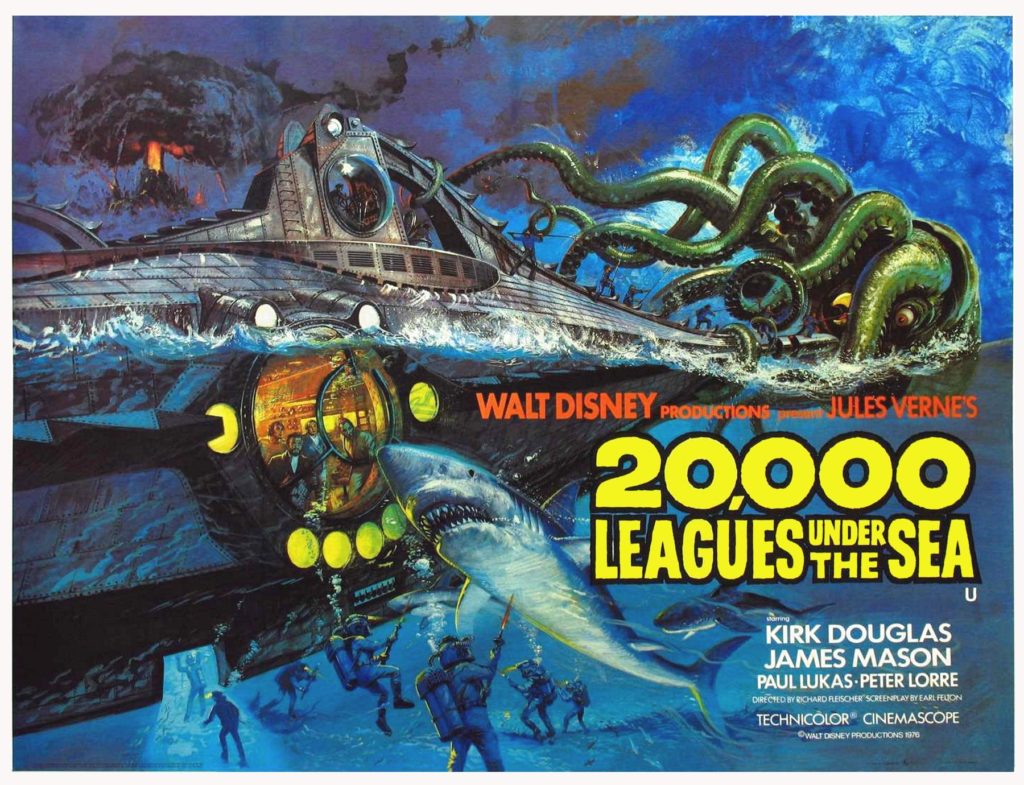

One certainty about pop culture is that it doesn’t stay the same for long. Though Westerns had been at their height during Disneyland’s 1950s design, Disney’s own 1954 film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea signaled the rise of another genre: fantasy.

Based on Jules Verne’s 1870s novel and produced by Walt Disney himself, 20,000 Leagues wasn’t just an Academy Award-winning classic; it was a revolution, launching Jules Verne’s uniquely sci-fi fantasy adventures into the popular lexicon. Studios rushed their own Verne adaptations into production, from 1959’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (from Fox), to Columbia Pictures’ Mysterious Island in 1961.

As a result, sci-fi fantasy became the dominant blockbuster genres of pop culture in the ’60s – The Time Machine, Barbarella, Planet of the Apes, Fantastic Voyage – making way for the more overt and crisp sci-fi of the ’70s – 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, the Andromeda Strain, THX 1138, Alien, and yes, Star Wars.

And here in the ’60s is where we stumble upon the story of the Imagineer central to today’s tale. Tony Baxter was just eight years old when Disneyland opened. Like so many Southern Californians, Disneyland was a part of his life. Scooping ice cream and (eventually) operating the Submarine Voyage had been his high school and college jobs! So when he was brought on to Imagineering in the late ’60s, straight out of school, he represented the first in a “Second Generation” of Disney designers – people who had never worked with Walt Disney, but who had experienced his park as a guest first.

Fittingly, one of Baxter’s first projects saw him paired with Disney Legend Claude Coats and shipped East to work on the version of the Submarine Voyage being designed for Walt Disney World. And of course, accounting for the pop culture that had developed around it, Magic Kingdom’s Submarine Voyage would trade in the Cold Way gray submarines of the strictly-scientific, Tomorrowland-set Disneyland ride for the Victorian steampunk retro-futuristic embellishments of the Nautilus.

Magic Kingdom opened with the Lost Legend: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea – Submarine Voyage – a fantasy-infused reimagining of Disneyland’s ride, casting off from Fantasyland on a fantastic underwater journey with added scenes to align to Jules Verne’s novel and Disney’s film adaptation of it. But neither Baxter nor Magic Kingdom was finished…

Rewriting history

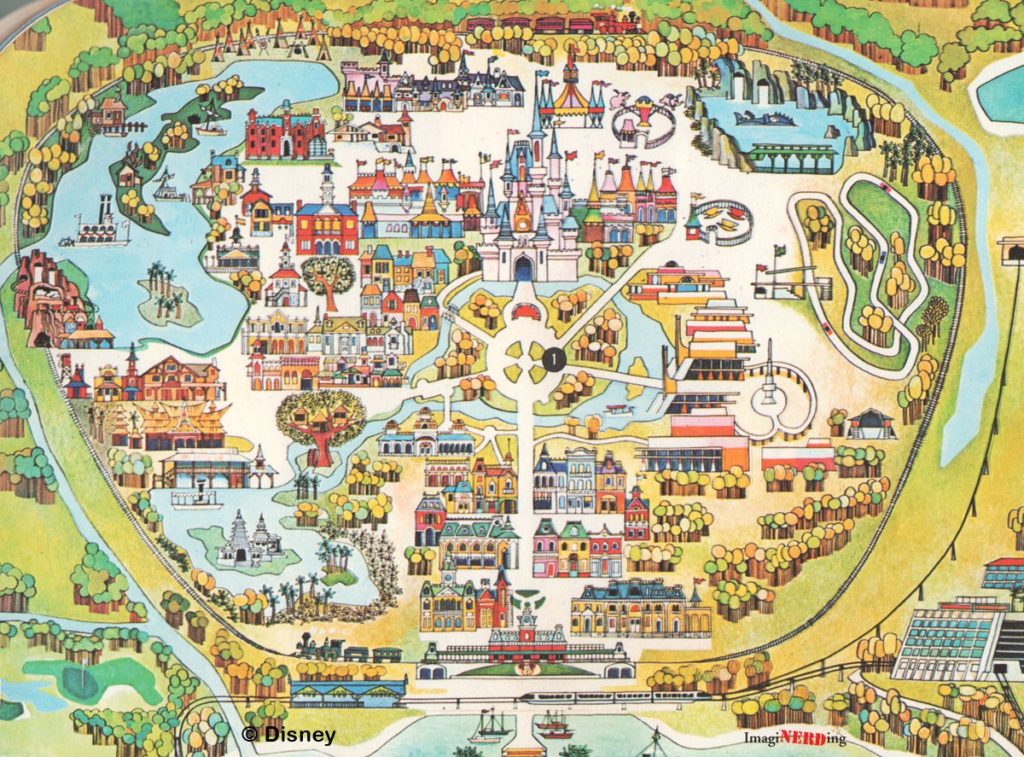

What would Imagineers do about Frontierland in an era when the allure of the Old West was waning? For one thing, Magic Kingdom didn’t contain a Living Desert or Nature’s Wonderland despite the unlimited space that would’ve made it practical. Instead, much of the land around the Rivers of America was dedicated to Liberty Square, with Frontierland merely a picturesque 1870s mining town on the outskirts of Adventureland. But Imagineers were hard at work on an answer to reviving interest in the Old West.

In fact, as the Magic Kingdom map above reveals, something big was en route to Frontierland. Without pop culture to back it up, Frontierland was a dusty concept; a glimpse back into the idling speed of the past. But Thunder Mesa would add some thrills.

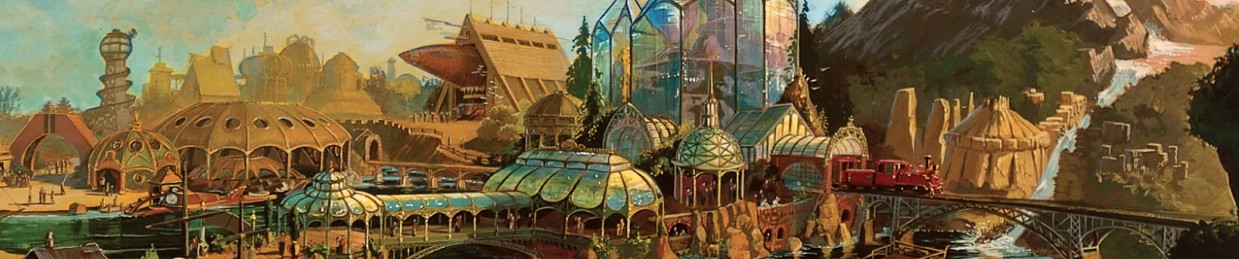

Imagined as a mega-complex containing multiple attractions, Thunder Mesa would’ve stretched along the Rivers of America’s western shores at Magic Kingdom. The project would imbue new relevance to the Old West by severing it from reality and envisioning a frontier stylized and amplified by the work of animator-turned-Imagineer Marc Davis.

The headlining ride of the complex would be an epic dark ride of massive scale. In fact, we sailed through the Possibilityland: Western River Expedition to see how Marc Davis would take the concepts he’d pioneered for Disneyland’s Pirates of the Caribbean and translate them east, rewriting the ride as a Western fable.

However, the complex would also include a log flume ride flowing around its exterior (sailing past wildlife vignettes and into day-glo caverns before splashing down in the Rivers of America) and a wild roller coaster wrapping around desert buttes, dipping over wooden trestles, and barreling across plateaus on a “runaway mine train” adventure. And guess who was designing that?

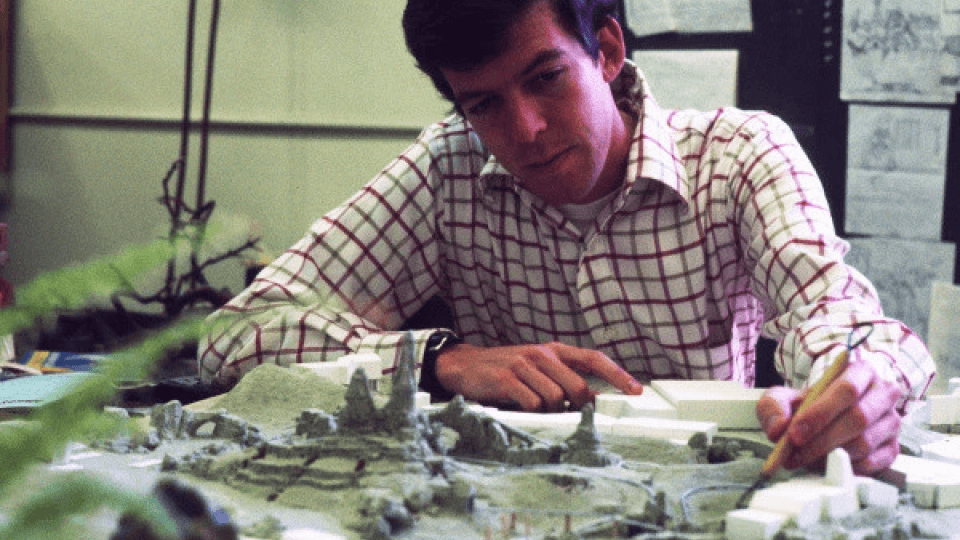

Yes, the young Tony Baxter had been put in charge of the mine train side project developed for Thunder Mesa. But as luck would have it, a few pieces fell into place.

The immense scale (and budget) of Thunder Mesa almost certainly had raised executives’ eyebrows given the decline of interest in the Old West and the rise of fantasy. To make matters worse, the ’70s are often recalled as the “Disney Dark Ages.” Without Walt at the helm, the studio was in sharp decline as it struggled to get its arms around what kinds of movies the public wanted. As a result, money was tight, and the lavish, oversized, epic dark rides of the ’60s (like Pirates, Haunted Mansion, and the proposed Western River Expedition) were simply out of the question.

For better or worse, Tony Baxter was allegedly advised by Disney’s then-CEO that if he thought his mine train coaster could be a star in its own right, he ought to split off of the Thunder Mesa project and pursue it. Of course, he did.

Big Thunder Mountain Railroad would essentially “fuse” the three Thunder Mesa attractions into a low-cost, high-thrill headliner that would add excitement and energy back into the dated concept of Frontierland and do so with the same budget-saving steel coaster technology that had made Space Mountain a hit in the era. But here’s the catch: it wouldn’t be alone…

Hints in the West

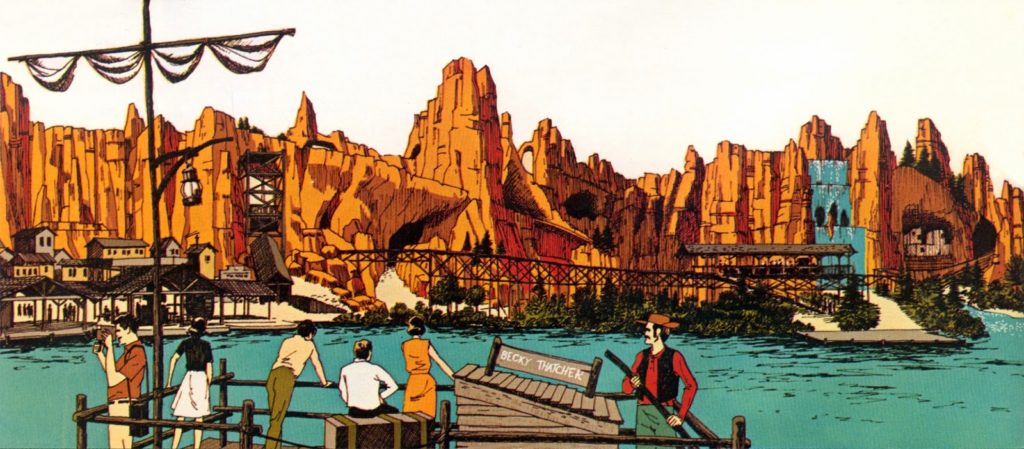

If you visit Frontierland in Orlando, Paris, or Tokyo, you’ll stand in awe of the towering, magnificent, grandiose Big Thunder Mountain. That’s by design. At all three, Big Thunder Mountain stands as the centerpiece of a sprawling, scrubby desert landscape with tall, harsh, geometric towers modeled after Arizona’s Monumental Valley. The sandstone buttes with iron oxide-rich siltstone layers resemble the Colorado Plateau – sharp, geometric, and monumental, as if chiseled and shaped.

It’s a perfect “Natural” Wonder for those three parks – each built on a magnificent scale. Imagineer Rolly Crump critcized Magic Kingdom’s castle for making him want to “genuflect,” and you can see that same reverence and scale here. It’s big. It’s expansive. It’s harsh. It’s an imposing and intimidating peak of Imagineering.

But as with all things, Disneyland is different. An enormous, sprawling harsh mountain looming over a vast desert in the diminuitive park would look sorely out of place, even if Imagineers could’ve made it fit in the former Nature’s Wonderland. So at Disneyland, Big Thunder Mountain isn’t based on Monument Valley at all, but on Utah’s Bryce Canyon.

While that distinction may seem trivial, it’s important. It’s not just that the rounded, otherworldly eroded “hoodoos” supernaturally set among evergreen forests in Bryce Canyon are less harsh and much subtler for Disneyland’s smaller scale…

It’s that Disneyland’s Big Thunder Mountain was meant to be just one piece of an entire new land at the park… Standing directly at the confluence of Fantasyland and Frontierland, this otherworldly mountain of inexplicable rock formations would be a bridge between narratives; it would reinvigorate the story of Frontierland by extending it.

After all, what would come of those prospectors who discovered gold in the rumbling caverns of Big Thunder? Would they settle down with their gold nuggets in the sleepy mining town of Rainbow Ridge? Of course not… They’d press onward! They’d take their winnings West, arriving back at that glowing golden port of immigrants, artists, writers, and adventurers from around the globe: San Francisco.

In the mid-70s, a new model on display in the Main Street Opera House’s preview area showed a brand new land that would join Disneyland by the bicentennial, set along the northern shores of the Rivers of America. As far as Tony Baxter was concerned, Big Thunder Mountain would be the start of the story of Discovery Bay.

Read on as we step inside…