More than skin deep

Arrow might’ve tried their best to replicate B&M stylistically, but they missed out very important key features that give B&M rides their effortlessly smooth, perfected paced ride experiences.

First, they kept to their own design and manufacturing methods. For better or worse, a signature element of Arrow’s design and manufacturing is that riders could actually look at the track ahead and see awkward transitions, angled bends, and abrupt directional changes. So apparent are these odd “snaps” in the track, riders could physically brace themselves against them!

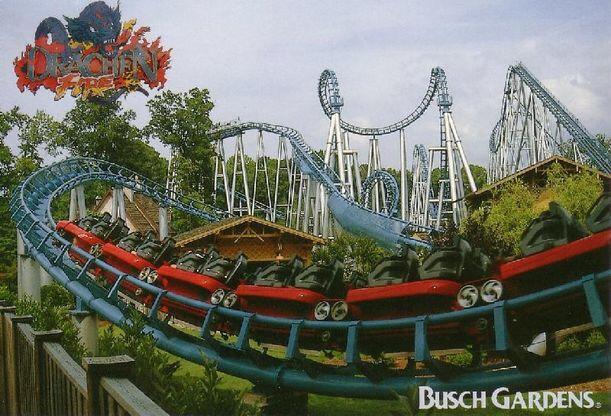

In Arrow’s first decades, this snapping track configuration was a byproduct of the time: without the aid of modern computers to calculate stress and strain, these odd bends in the track would be taken at unpredictable speeds, leading to that “headbanging” and snapping that send riders heads clanging between the over-the-shoulder restraints. Though Drachen Fire’s manufacturing did use early computer simulation, it didn’t do much to quell the issues other Arrow creations faced. Even as a product of the 1990s, Drachen Fire had all the ingredients of a 1970s Arrow coaster.

Put another way: even if Drachen Fire looked like a B&M, it felt like an Arrow… something that riders would find increasingly unacceptable as B&M’s ultra-smooth rides started to appear in parks, including at Busch Gardens with Alpengeist just a few years later.

Second, Arrow missed one key concept B&M works off of: riders’ heartlines. B&M (and all modern coaster manufacturers) can use computer simulations to ensure that every inversion and bend in the track is expertly navigated by trains that are built to emphasize a rider’s “heartline.” Picture a corkscrew as you think of it this way: on an Arrow coaster, you bend around the track; on a B&M coaster, the track bends around you. The idea is that by keeping a rider’s heart at the same level, inversions are comfortable and perfectly paced. B&M’s trains keep the center of gravity perfectly placed on riders’ heartlines, led by a weighted “zero-car” that keeps the train’s speed steady.

Sure, roller coaster enthusiasts might have momentarily thought that Drachen Fire was the counterpart to Kumba, but one ride would announce otherwise.

The End

Soon after its debut, Drachen Fire gained a reputation for roughness, far and above even the typical discomfort from Arrow’s multi-loop coasters. Before the 1994 season, the corkscrew right after the ride’s mid-course brakes (one of the two “interlocking” corkscrews) was removed entirely and replaced with a straight section of track. Trim brakes were added to the new track section (meant to pull back on the train and slow it down before it entered the cutback element) all in an effort to reduce the head-banging riders experienced.

It was at this same time that the park began to advise guests to remove their earrings prior to riding. While it might’ve seemed overdramatic, this was no empty threat, as the headbanging throughout the ride left many guests with unforgettable memories of Drachen Fire’s wrath.

In 1996, actor Alex Winter visited the park as part of the E! television network’s “Theme Parks a Go-Go” television special and commented on-camera after the ride that he would need a new spine. Ridership fell year after year until a final death blow…

In 1997, B&M’s Alpengeist opened in the park’s German Rhinefeld area. The exquisite coaster from the still-young B&M gave Busch Gardens Williamsburg its first B&M and its own Inverted roller coaster; a perfect pair with Tampa’s renowned Montu and a brilliant evolution of the world-famous Batman: The Ride. Alpengeist is a wild, soaring, out-of-control coaster that flips riders upside down six times through six different kinds of inversions. But it’s also smooth. Very smooth. Every bit a B&M, it’s an impressive and reliably fun ride.

Proof that even intense roller coasters could be comfortable and fun must’ve begun to change hearts and minds at Busch Gardens.

Drachen Fire closed during the middle of the 1998 season. The park’s public relations director, Cindy Sarko, commented, “There has been a steady erosion of ridership, combined with the high operating expenses of the ride, it helps officials make the decision to shut it down.” There was no estimate of when the ride would reopen, though officials did say they planned to modify it.

In 1999, the ride was listed for sale. “We had several inquiries from potential buyers, but for various reasons we couldn’t reach any agreements.” So the ride stood.

In 2001 – three years after it closed – during a Passholder Preview day at the start of the park’s season, trains cycled through the ride as if it were readying to open. But it didn’t. When the park opened in 2002, Drachen Fire was gone. After just over five years of operation, the ride was no more, and Kumba was an only-child.

Extinguishing the flame

Drachen Fire was indeed a Franken-coaster; one manufacturer’s best attempt at recreating another’s. It was odd, uncomfortable, and unfortunate, and to this day remains one of the most short-lived roller coasters on Earth.

It’s strange that we’ve chronicled two very different closed rides at one park: the beloved Lost Legend: The Big Bad Wolf that operated for a quarter-of-a-century before being removed despite the pleading of fans, and Drachen Fire, lasting barely a fifth of that time.

Whatever the case, Drachen Fire’s story is a unique one. It’s unlikely that we’ll ever see anything quite as strange happen to a roller coaster ever again. And honestly, that may be a very good thing.

B&M had never built any cobra rolls or interlocking corkscrews as of 1992. Arrow didn’t really have any existing coasters to mimic, just plans for something brand new that failed for them (and worked for B&M)

DrachenFire is probably my favorite coaster, along with Grizzly, the roughness of each being the primary draw. Drachen drew blood by jamming the posts of a friend’s earrings into her neck. I was sad to see it go.