Let’s review…

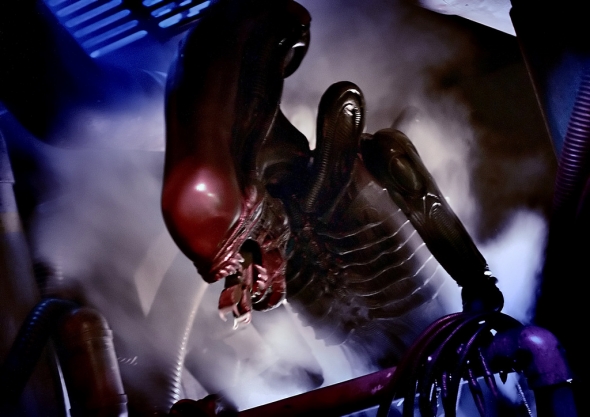

In the 1980s, films like Star Wars (1977) and Alien (1979) had not just jumpstarted a renewed interest in science fiction; they had fundamentally reshaped our cultural collectively shared image of the future. Meanwhile, Michael Eisner had overseen the opening of both Captain EO and STAR TOURS, signaling a new path forward for Disney Parks — incorporating the films, characters, and stories that mattered — all in hopes of attracting thrill-seekers, movie-lovers, and even teenagers to see Disney Parks differently.

And here’s the setting where those two narratives collide: Tomorrowland.

Yesterday, today, and Tomorrowland

Time and time again, Imagineers have come head-to-head with “The Tomorrowland Problem” — the inevitable inability to keep Tomorrowland looking like tomorrow.

Think about it: when Disneyland opened in 1955, its Tomorrowland was set in 1986 — immeasurably far off for mid-century audiences! (And honestly, consider if Tomorrowland today were determined to accurately showcase what technology, architecture, and culture would be like in 2050…)

Given just how unlikely it seems, Walt and his designers actually did a respectable job envisioning the look and feel of the Space Age, even if that opening day Tomorrowland would be laughably retro by today’s standards.

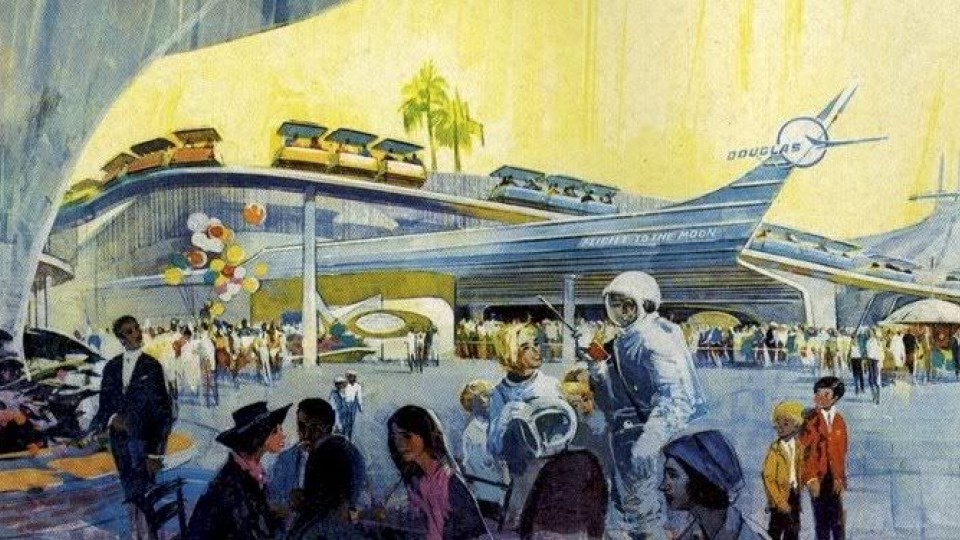

Take, for example, ROCKET TO THE MOON — a (motion-less) simulator located in Tomorrowland (above). The premise of the attraction was that by 1986, Trans World Airlines (TWA) would be offering 8-hour commercial flights to the moon, and that guests could get a glimpse of this really-for-real prediction at Disneyland today.

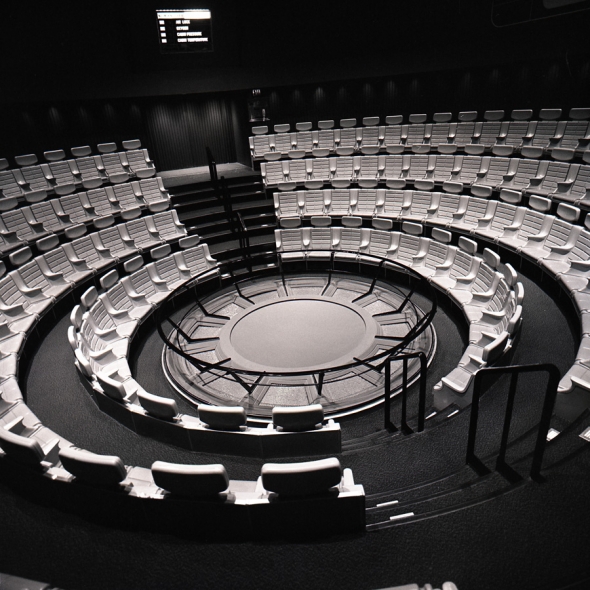

Guests would be routed to one of two domed theaters, and seated in concentric tiers around projected “windows” embedded in the floor and ceiling. Given that Sputnik-1 — the Earth’s first artificial satellite — wouldn’t launch until 1957, the simple premise of a trip to the moon was sincerely futuristic in 1955, even if the film guests saw through those “windows” dreamed of extravagent alien cities on the far side of the moon…

But barely a decade later, the “Tomorrowland Problem” struck. By the mid-1960s, America was in the midst of the Space Age; a generation was shaped by America’s race to the moon and the mid-century stylings that came with it. The world was alight with neon signs, doo-wop music, and mid-century modern architecture marked by curves, parabolas, boomerangs, and upswept roofs, and Disneyland’s Tomorrowland suddenly didn’t look like the future at all.

In 1967 — just a few months after Walt’s death — Disneyland debuted an electric New Tomorrowland. Though it may have taken a complete rebuild from scratch, Tomorrowland at last felt like it aligned with the prevailing pop culture of the era — a “World on the Move” marked by spinning rockets and sleek Googie curves; a land embracing the wonders of the Atomic Age via the Lost Legend: Adventure Thru Inner Space while setting the stage for the sleek, Space Age brilliance of the Modern Marvel: Space Mountain, and with the zippy Lost Legend: The Peoplemover and its pastel cabs darting to-and-fro through an effortless, white, geometric land.

And in fact, let’s keep following the thread of that theater-in-the-round Rocket to the Moon attraction. In the midst of the Space Race, Disney’s decade-old attraction about the moon was a laughable relic, necessitating its update to FLIGHT TO THE MOON, a more scientific (and timely) journey fit for the 1967 mid-century modern rebirth of the land… Which would’ve been all well and good except that just two years later, NASA’s Apollo 11 manned mission actually made it to the moon, dating the attraction considerably. Yep — the “Tomorrowland Problem” again. Trips to the moon were no longer the stuff of the future… they were headlining news!

When Magic Kingdom opened in 1971, its unfinished Tomorrowland had taken many of the best aspects of Disneyland’s Space Age iteration of the land, expanding with bolder, monumental architectural touches of the ’70s. It even borrowed the contents of the Californian land, including the dual theaters of the already-outdated Flight to the Moon (in the northern showbuilding along the land’s mirrored promenade entry, on the left above).

It wasn’t until 1975 — seven years after the real moon landing — that Magic Kingdom’s Tomorrowland was completed and Disney updated both attractions simultaneously to MISSION TO MARS; a third version in twenty years needed to keep these Tomorrowland attractions looking sincerely forward-thinking to audiences….

And even in 1992 — nearly two decades after Mission to Mars launched — that theater-in-the-round attraction will still playing to audiences at Disneyland and Magic Kingdom! Yes, a two-decade-old ride film in Tomorrowland. But Mission to Mars was the least of Tomorrowland’s worries. Both versions of the land — Disneyland’s (1967) and Magic Kingdom’s (1975) — were as good as dead.

The Tomorrowland Solution

Don’t misunderstand — those Space Age-inspired Tomorrowlands remain the most iconic and sought-after versions of the lands… even for Imagineering fans who never saw them in person! And it’s true that, even in the 2020s, that simple, nostalgic, optimistic, mid-century view of tomorrow feels like an evergreen, timeless, retro-future… a reminder of the wonders of the Space Age.

But we have to remember that, in the ’80s and ’90s, pop culture had moved on. Films like Star Wars and Alien had completely rewritten America’s shared image of tomorrow… For a brief blip of time, that naive mid-century Tomorrowland wasn’t old enough to be retro, or new enough to be cool.

As executives stared down the barrel of yet another facelift for Tomorrowland, they mulled over that longstanding “Tomorrowland Problem,” knowing full well that no matter how much money they through at it, any Tomorrowland determined to actually predict the future was bound to fall behind. Eventually, Tomorrowland would need reimagined again in continuous and costly updates… forever.

Unless, that is, designers could find a way to change Tomorrowland at its core.

In 1992, Disneyland Paris opened. Given the extensive reimagining needed to make the park feel at home in Europe, designers had gone back to the drawing board on many Disneyland staples to sap the inherent Americana in favor of a more European-friendly literary romanticism. Tomorrowland, for example, was entirely missing from the European park’s lineup, replaced with Discoveryland — a land inspired by great European fantasy writers. Replacing rockets and saucers with zephyrs and the Nautilus, the land even had its own Lost Legend: Space Mountain — De la Terre á la Lune, interpolating Jules Verne’s novel of the same name.

Discoveryland didn’t even try to predict the actual, scientific advancements of tomorrow, or to imagine the architecture and attitudes of the future. By being rooted in the past, this was a “Tomorrowland” that would never need updating! It was timeless! And so, the race was on to design similarly evergreen styles for the Tomorrowlands in California and Florida…

A recipe for disaster?

Standing in the early 1990s, we’ve collected all the ingredients we’ll need. The recipe is simple.

Take a dash of Michael Eisner’s obsession with cool, hip, edgy, cinematic attractions — and his willingness to fund them; add two outdated Tomorrowlands, each needing a full reimagining; mix in a requirement that those New New Tomorrowlands needed to be the last facelifts for the lands — timelessly rooted in fantasy, history, or fiction; knead in the bleak futurism of the ’80s shaped by Star Wars and Alien; and finally, add a dash of Imagineers’ covert plans to bring Alien to Disney Parks…

Blend it all together and that newest generation of Disney’s designers had developed a win-win concept that would terrify teens, impress Eisner, and keep costs low… Which brings us to the secret ingredient:

A-ha! Those Mission to Mars theaters, still playing a tired film from the ’70s at both Disneyland and Magic Kingdom…

Sure, the gun-blasting dark ride through the Nostromo was out — deemed too intense and too violent for Disneyland… But with just a few tweaks, the tired and passive Mission to Mars theater in California could become a next generation Alien attraction; a multi-sensory special effects show using Audio-Animatronics, cutting edge binaural sound (used to great delight in the post-show for MGM Studios’ Monster Sound Show), and special effects embedded in the seats to release the Xenomorph into the unsuspecting crowd…

When they presented their idea to Eisner, he beamed. It was perfect. Re-using much of the former theater would keep installation costs low, and this new concept — this “Alien Encounter” — was simple enough to export a clone to each Tomorrowland as they got their own respective renovations.

The Alien advantage

Then there was the best news yet: exit surveys of guests leaving Magic Kingdom reported that 80% of adult visitors had seen Alien. That meant that explicitly using the Alien film tie-in and the Xenomorph provided this “Alien Encounter” with three invaluable commodities:

- The attraction could market itself. Like Star Tours, Alien had a built-in following that would be dying to try the new attraction. Just hearing that such an incredible film now had an associated show at Disney would attract thrill-seekers who would be dying to see what Disney had done.

- An official Alien attraction had built-in parental controls. If 80% of guests recognized the R-rated film and its horrific creature, they would also recognize how intense an associated attraction was bound to be. If you wouldn’t let your child watch Alien, then you’d already know to not let your child experience the Alien attraction. No need for constant warnings in the queue; Alien speaks for itself.

- Imagineers wouldn’t have to waste precious attraction time introducing the setting or creature since guests would come into the experience with at least some prior knowledge about the alien and its abilities, the Weyland-Yutani Corporation, the Nostromo… Every second that didn’t have to be spent establishing a mood or character could instead be put to good use in the show itself.

Eisner was allegedly thrilled and greenlit the project hoping to quickly add another thrilling attraction to Imagineering’s portfolio. But the senior Imagineers were still horrified. They were sure that all this Alien nonsense was behind them. Now, this upstart group of new designers had somehow conned Eisner into thinking that an R-rated film was appropriate for Disney Parks, again. What would Walt have said?!

Behind the back of the now-official Alien Encounter team, the senior Imagineers allegedly went to none other than George Lucas with a plea to help set Eisner straight. Lucas agreed that Alien probably was a little too intense for Disney, and offered to speak to Eisner on behalf of the senior Imagineers and voice their concerns to him.

Apparently based on what Lucas told him, Eisner returned to the Alien Encounter team with yet another change of heart. He told them that he had decided against using Fox’s signature, R-rated Alien, but that he still loved their plans for converting the Mission to Mars theater, and was confident they could come up with something just slightly less frightening to be the basis for their Alien Encounter. The team recoiled. They wondered if the attraction could even work without the Xenomorph. They’d suddenly lost their built-in marketing, parental controls, and backstory.

What did they come up with? We’ll step into Alien Encounter on the next page… but we bet it’s not the Alien Encounter you expect or in the park you think… Read on…