Moving the future

By the close of the 1964 – 65 New York World’s Fair, Walt was able to dedicate himself to his biggest projects yet. It’s no secret to Disney fans that, by the mid-1960s, Walt’s focus had shifted from Disneyland to “The Florida Project.” After years of covertly acquiring land holdings in swampy Central Florida, Walt owned up to his plans for a “Disney World” that would be a blank canvas for experimentation. And though Walt was willing to build a “Disneyland East” there as a concession, his real ambitions had grown.

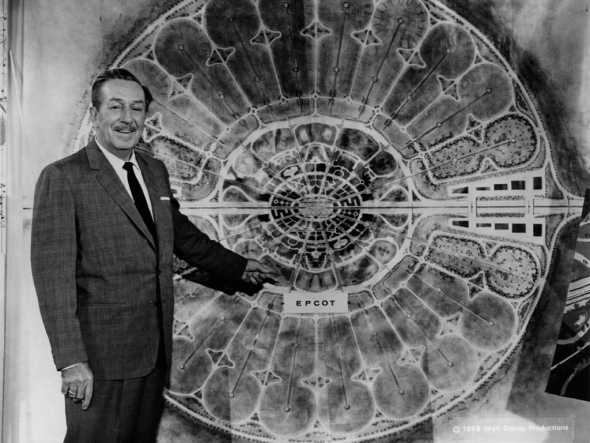

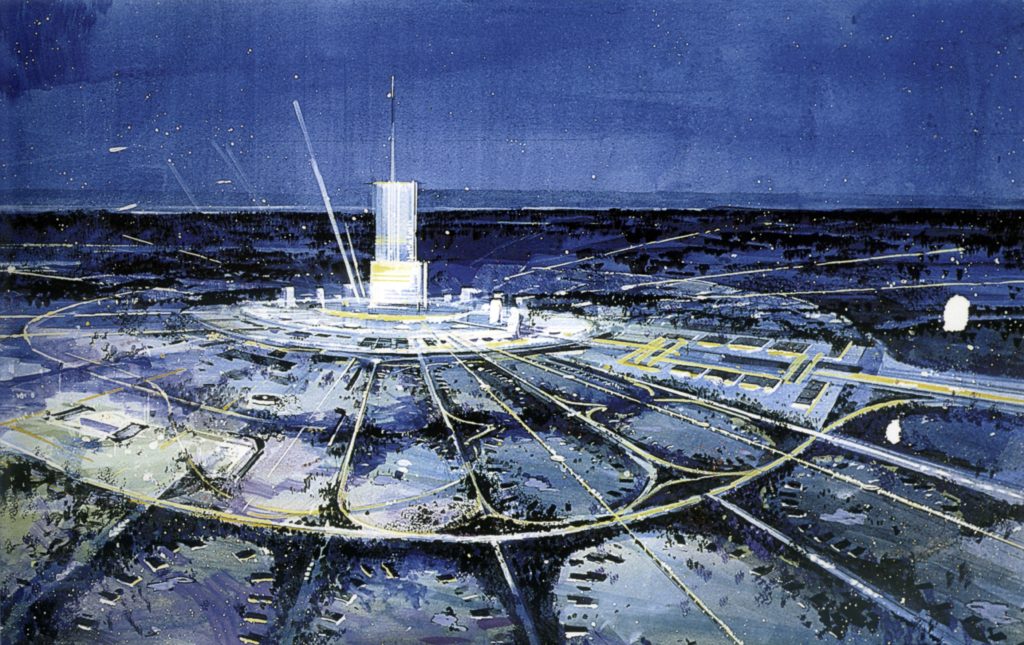

In fact, Walt’s dreams of an Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow are worth a dissertation in their own right. Suffice it to say that this malleable metropolis would’ve been a real city where people would live, work, and play; a living laboratory where the newest household and urban innovations would be constantly tested, serving as a blueprint for all global cities after.

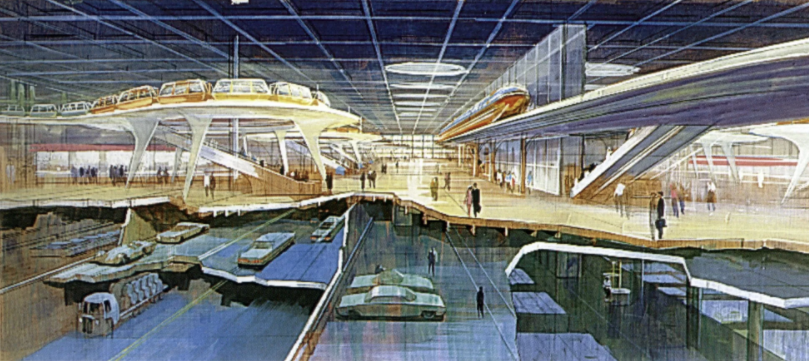

Ever the futurist, Walt had big plans for his E.P.C.O.T. to change the world, and one of the most vital components was reimagining transportation. To his thinking, the 1959 installation of the Monorail at Disneyland had merely been a test… a prototype disguised as a ride, serving to introduce the public to a new, efficient mass transit system. And what Disneyland had tested, E.P.C.O.T. would now make real. Monorails would sail through the city center, connecting E.P.C.O.T. to the theme park, the Disney World Airport, and Lake Buena Vista residential community.

And from there, an entirely new system would take over. Like capillaries filtering into the finer points of the Florida property, Walt and his team envisioned Peoplemovers – continuously-moving, high-capacity, mass-transit lines that would radiate through the property, modeling a new and effortless urban transit solution for the world. Residents of EPCOT would use Peoplemovers to commute to work and keep the city’s center traffic-free.

Walt Disney had an idea. Thanks to the World’s Fair, he had the technology to bring it to life. And thanks to Tomorrowland, he had just the place to test it…

The Tomorrowland Problem

Hang around Disney Parks long enough, and you’re guarunteed to see it in action: the “Tomorrowland problem.” As Walt himself would admit, from day one, Tomorrowland had a tough time keeping up. Unfortunately, the closer designers get to sincerely predicting the textures and technologies of tomorrow, the more they risk Tomorrowland becoming Todayland.

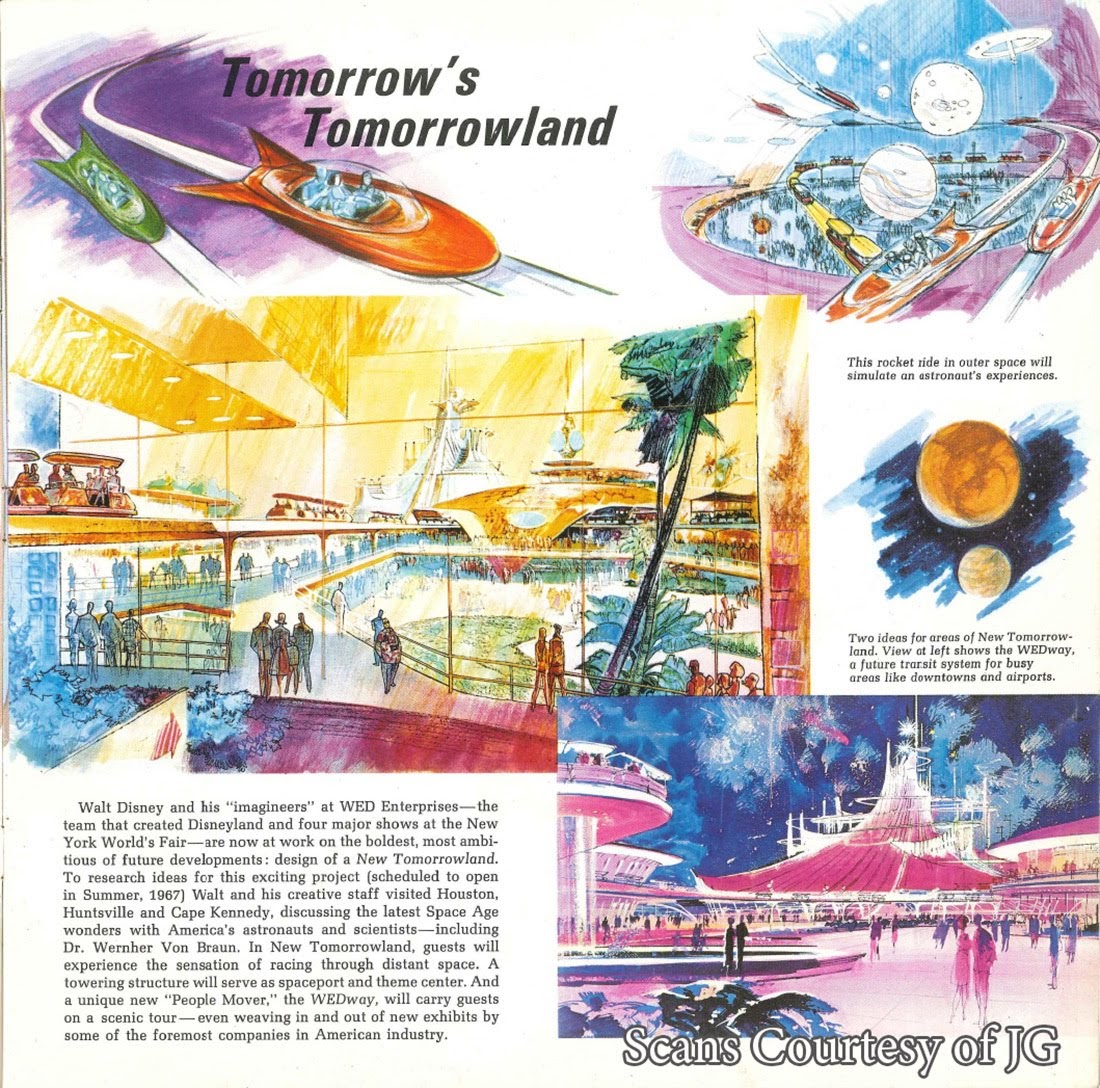

Though Imagineers had done a bang-up job envisioning the future from the ’50s, even a decade into the park’s lifetime, it just wasn’t holding up. The Space Age was in full swing, and the hard corners, checkered flags, and brutal concrete of Tomorrowland looked entirely at odds with the sleek curves, bounding parabolas, and pastel accents that would define futurism in the ’60s and ’70s.

Given that Walt had never been happy with the original Tomorrowland and that the advances of the World’s Fair (and his dreams of E.P.C.O.T.) now empowered Imagineers with unprecedented tools, the time was right… A floor-to-ceiling renovation was in order, and Walt’s Tomorrowland would soon take shape….

A World on the Move

Walt Disney didn’t live to see the glorious renovations of Tomorrowland developed throughout the 1960s. New Tomorrowland would open on July 2, 1967 – seven months after his unexpected death. Still, Walt’s DNA was present in most every corner of the land.

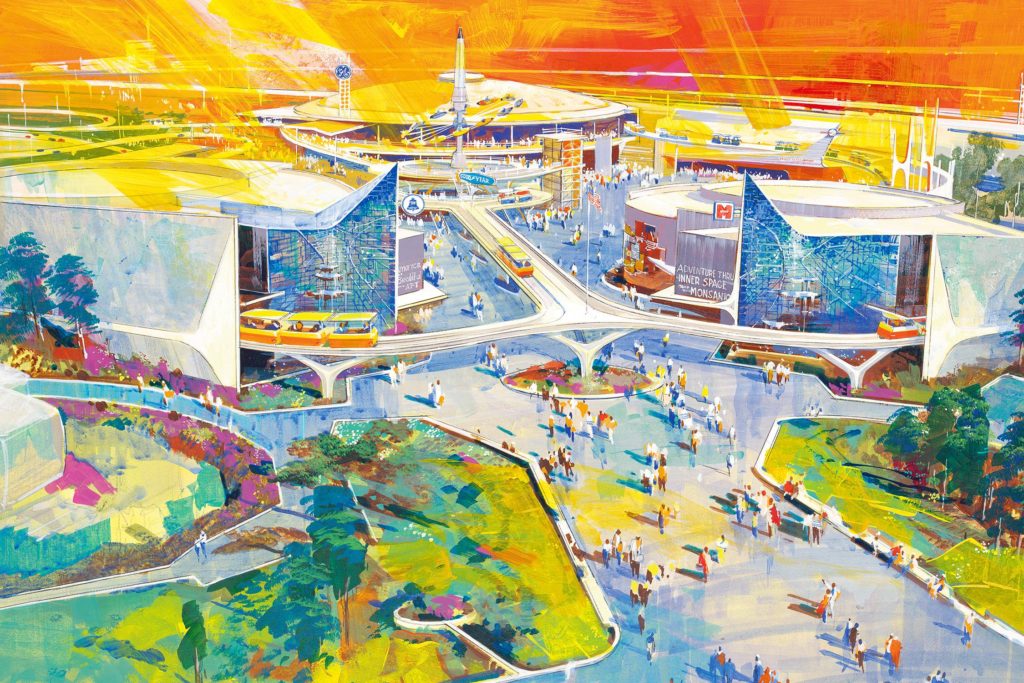

Completely reborn, this New Tomorrowland was redesigned from the ground up – new buildings, new textures, new colors, and new attractions. If the park’s Frontierland represents the past with its cumbersome riverboats, plodding mules, and idling speed, Tomorrowland would be our future – a “World on the Move.” And indeed, this land was marked by kinetic energy all around.

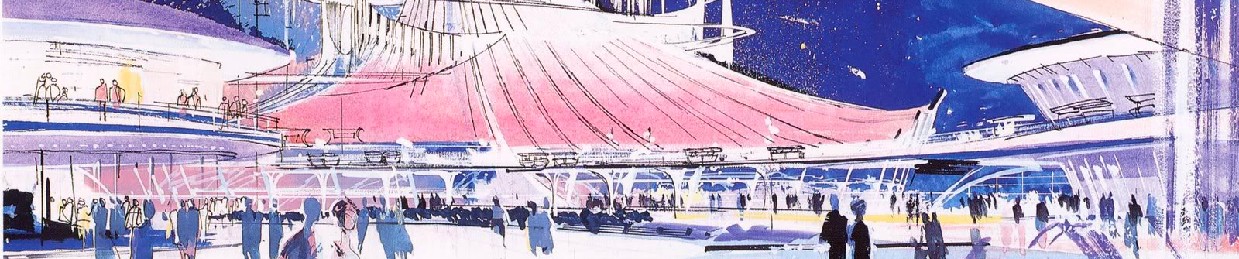

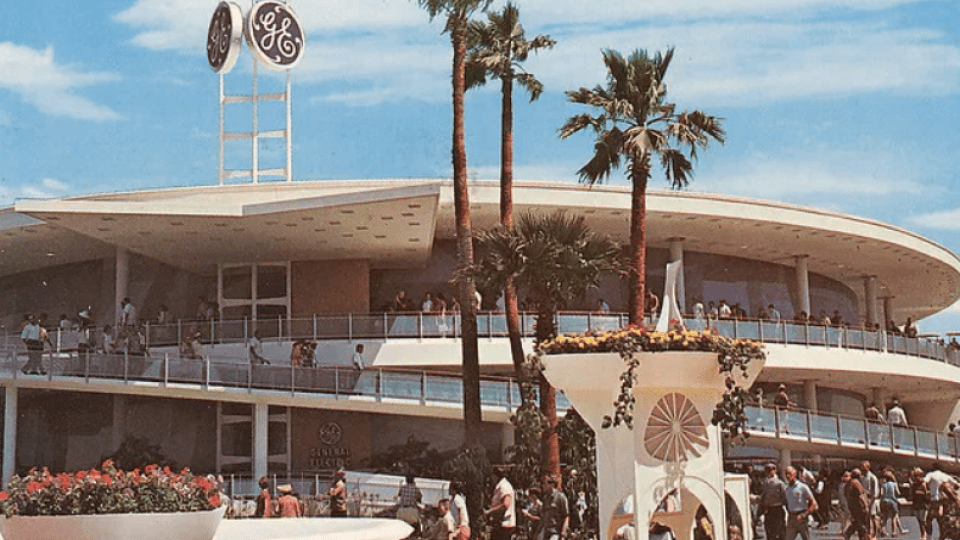

Now dressed in the sleek and purposeful dressings of the Space Age, New Tomorrowland was a utopia that perfectly encapsulated the future as seen from the 60s and 70s. The land’s harsh right angles and simple geometry had disappeared, replaced with sleek, streamlined simplicity… It was a masterwork of mid-century modern architecture – aerodynamic curves, upswept roofs, gentle and organic shapes, and a neon glow. The perfect union of form and function, the land was now two-stories tall, drawing the eyes ever skyward.

Two mirrored show buildings flanking the land’s main entry path contained new attractions. The northern showbuilding contained an expanded and remastered Circle-Vision, presented via nine screens surrounding standing guests. The southern contained one of Disney’s most legendary dark rides ever – the Lost Legend: Adventure Thru Inner Space, debuting the Omnimover ride system in a spectacularly scientific attraction shrinking guests to the size of an atom (born of Walt’s optimism around the promise of the Atomic Age).

Meanwhile, the very rear of the land was equipped with its own revolving theater, built from scratch to house the Modern Marvel: Carousel of Progress (newly transported to Anaheim from the World’s Fair).

Nearby, Flight to the Moon and its simulated space voyage theaters were cutting edge compared to the original Rocket to the Moon that had come before.

And then, the land’s center, the new Rocket Jets were positioned high atop a three-story pedestal with a Space Age red gantry lift as their only access point. With the Rocket Jets revolving above, the Submarine Voyage gliding below, and the Monorail soaring throughout, Tomorrowland really was a World on the Move with something new to see in every direction. But this two-story Tomorrowland featured one timeless attraction that today’s Disney fans deify.

Let’s travel back to 1967 and head toward it…

A highway in the sky

No matter where you step in this kinetic Tomorrowland, it’s hard to miss the PeopleMover as it bobs and weaves, gliding cheerily through the skies. Supported by elegant white trunks growing up from the ground, the gleaming tracks are practically icon of the land, visible from most anywhere as they weave into and out of each of the land’s interconnected buildings.

But how do we climb aboard? Frankly, that’s part of the fun. At the base of the white pedestal that the Rocket Jets revolve over, the way to the PeopleMover is a “speed ramp” that carries us to the second level of the land’s central icon. There, the speed ramp deposits us at the start of another continuously moving sidewalk (this one flat) advancing at about 1½ miles per hour. As we step onto it, we find ourselves carried along, aligning effortlessly with a chain of PeopleMover cabs arriving at the same sped, their roofs tipped back and doors slotted open, waiting for us.

Watch you head and step! Once on board, get cozy – we’ll be here for over fifteen minutes, relaxing in the California sun and enjoying unbeatable views of this Space Age playground.

As the train slowly advances out of the pedestal’s circular loading area, you might notice that a portion of the train ahead breaks off from the slow-moving continuous stream through the station. As if by magic, this newly-cut segment zips off down a straightaway, ducking into a showbuilding. But now, it’s our turn. With an effortless boost, our train now speeds up to 7 miles per hour, floating weightlessly down the central spine of track running through the center of the land’s entry path. Wave to the folks below, and to the returning PeopleMovers on the right, en route back to the pedestal!

But now, ahead, the path forks. Ours heads off to the left… Ready to see what’s inside? Before we do, let’s take a quick detour to explain the technology that’s powered the PeopleMover so far…

The mechanics

The continuous and gentle glide of the PeopleMover through the skies of Tomorrowland felt almost like magic. So how did it work? What complex computer systems controlled the acceleration of the train segments, keeping vehicles appropriately spaced and paced?

Here’s where the World’s Fair comes back into play. Disney had premiered four attractions at the World’s Fair. Three of them – Mr. Lincoln, “small world,” and Carousel of Progress – had very directly been transplanted to California in the years following the fair. The only one that hadn’t made the transition was Ford’s Magic Skyway, with its motorless convertible cars soaring along the track through Ford’s pavilion. But that doesn’t mean the technology didn’t.

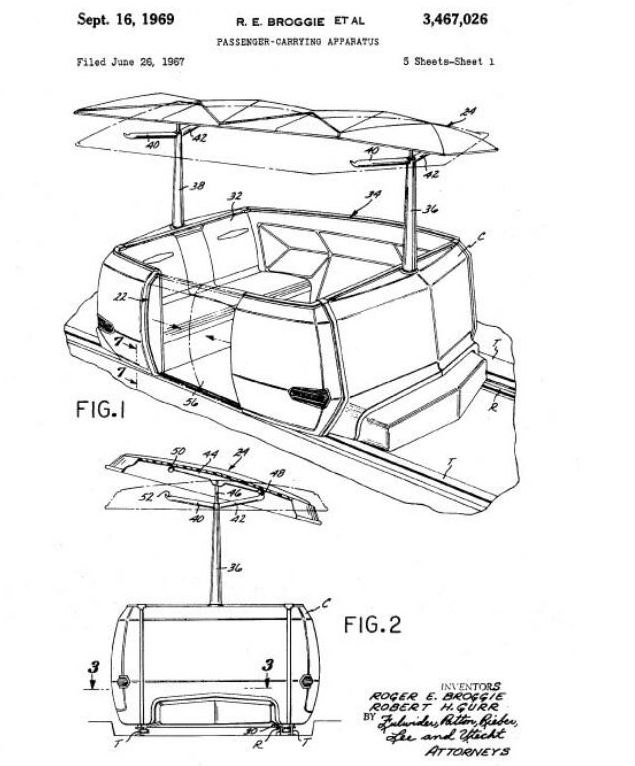

The PeopleMover borrowed much of the technology behind the Ford attraction. With its constantly-moving trains that allowed continuous boarding, the PeopleMover offered a theoretical (and often met) hourly capacity of 4,885 guests per hour – tremendously high, and double the capacity of even the most efficient rides today. Most impressively, the vehicles were lightweight and motorless, with no moving parts whatsoever beyond the door and tilting roof for loading – another masterwork by Disney Legend Bob Gurr (who once said “if it moves on wheels at Disneyland, I probably designed it”).

There’s no need for a propulsion system or even a computer system aboard the PeopleMover. Instead, the attraction was entirely powered through the track. About every nine feet, the train would pass over a Goodyear tire embedded in the track. Those tires were turned via an attached electric motor. In fact, 517 motor-driven tires were placed along the ¾ mile track of the PeopleMover, each motor providing up to 3 horsepower to control the speed of the attraction by simply adjusting the speed of the turning tire.

Using this spectacularly simple and impressively innovative technology, the 16-minute journey through Tomorrowland sent the PeopleMover trains gliding up and down hills, through curves, and into the show buildings of Tomorrowland for sneak peaks of the land’s attractions. So let’s hop back on board to see exactly what the PeopleMover has in store… Read on…