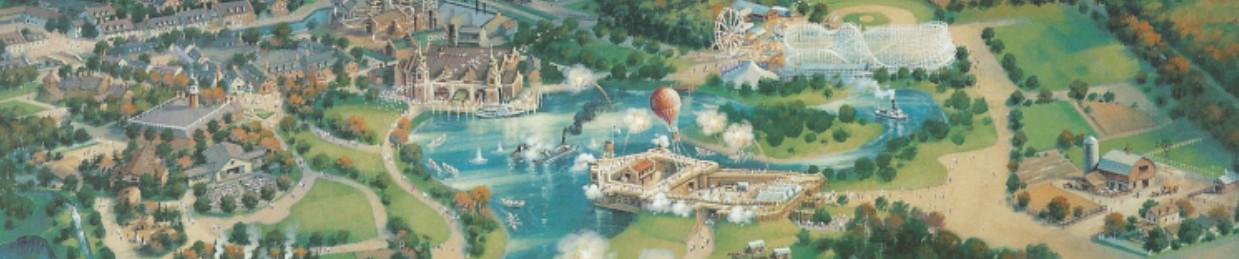

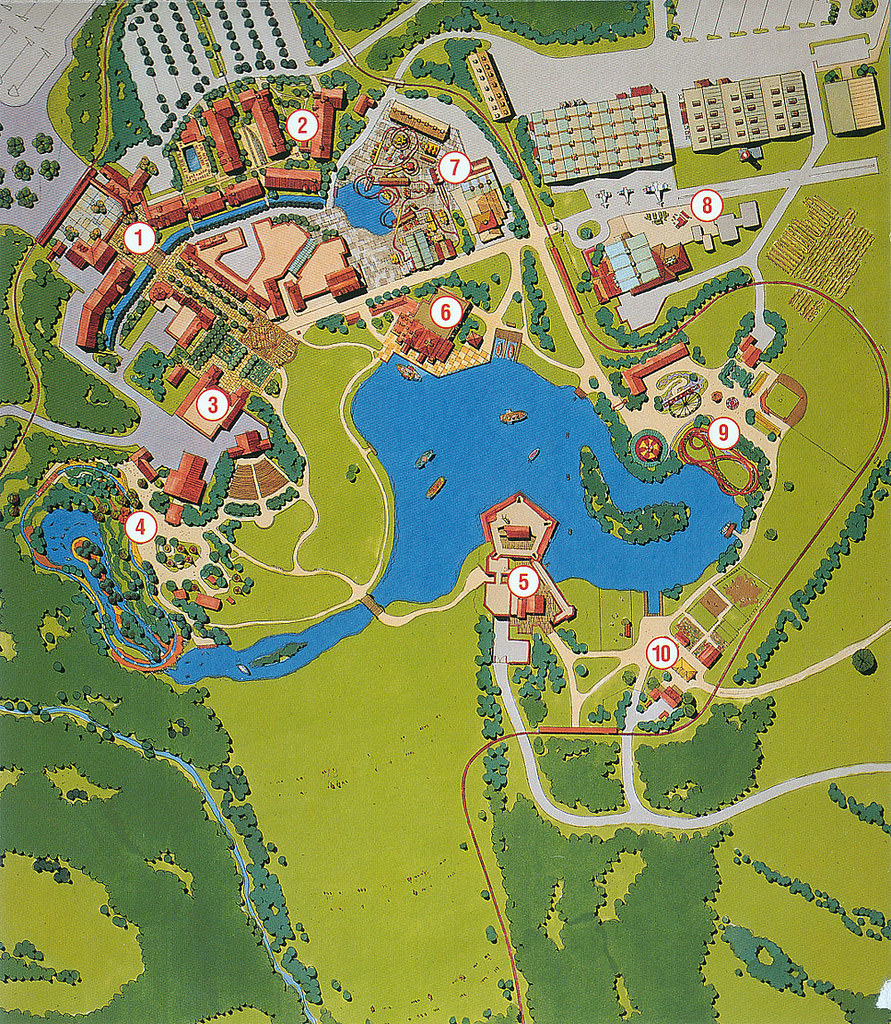

Typically, one of the signature elements of Disney Imagineering concept art is how little is really shown, with details obscured by lens flare, fireworks, and hot air balloons. But since Disney’s America was official, information about this smaller, “regional” take on a Disney park and the concept art for it is surprisingly clear, up to and including the beautiful concept art above (which can be made larger by clicking) and logistical aerial layouts for the park we’ll reference below (at the top and bottom of the next section for your reference).

Like Disneyland, Disney’s America would’ve been divided into nine themed lands. Let’s head inside.

Inside Disney’s America

Disneyland’s entrance is Main Street, U.S.A. – a typical Midwestern town at the turn of the 20th century, alight with the brand new electric lightbulb. But here in Disney’s America, our journey starts nearly a century earlier.

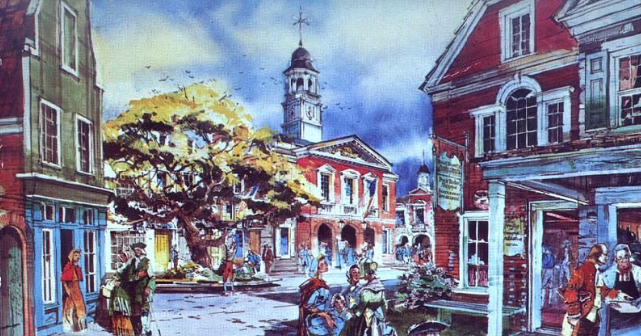

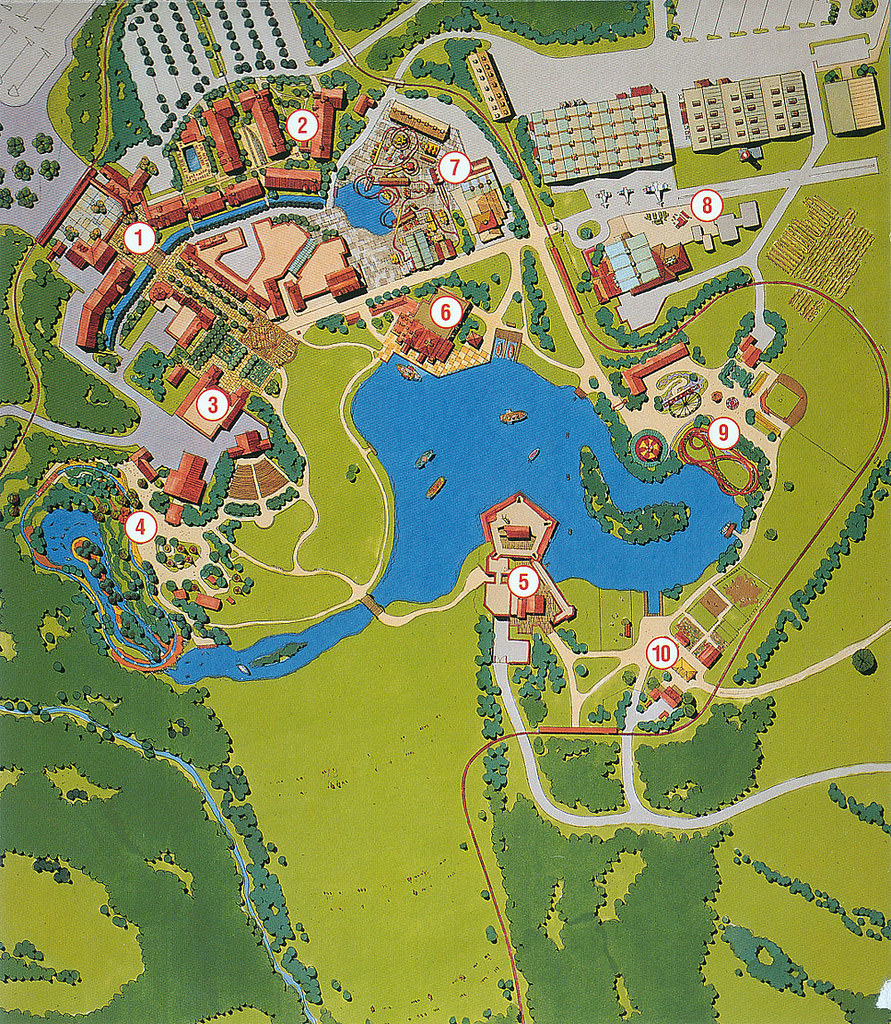

We enter Disney’s America (in true Disney fashion) by passing under an 1840s train trestle (where we might choose to start our historic adventure by boarding a steam locomotive that circumnavigates the park and heads out into the beautiful forests of Virginia en route to a grand circle tour). Once inside, we find ourselves in Crossroads, U.S.A. (1) (on the map above) – a bustling 1800s town.

This is a fledgling nation not yet torn asunder by the Civil War. While the streets of this land would be alive with merchants and living history exhibits, the second and third stories of these buildings would be a cleverly-integrated, historical, and inconspicuous hotel (2), with premium rooms overlooking the canals and marketplaces of town.

Traveling counterclockwise around the park’s central lagoon, we find ourselves back in time, along the red-brick colonial streets of New England. This is, of course, President’s Square (3), a regal courtyard celebrating the birth of democracy from 1750 to 1800, with The Hall of Presidents as its signature attraction.

An outdoor amphitheater around the corner bridges the gap to the next themed land, Native America (4). While Disneyland’s early “Indian War Village” may seem positively barbaric by today’s standards (even though it was quite accurate and culturally competent for the time), Native America would be a land set aisde to honor local First Nations by displaying their people, pride, and stories well, with interactive experiences, arts, and exhibits compiled with Native Americans.

That said, its anchor attraction would still be Lewis & Clark’s River Expedition – Disney’s first river rafting ride – departing from Native America and tracing the fabled 1804 – 1806 Corps of Discovery Expedition that set out from St. Louis in search of a water route to the Pacific Ocean. It’s likely that the rapids ride would’ve passed scenes of wildlife and other natural wonders encountered by the cross-country expedition.

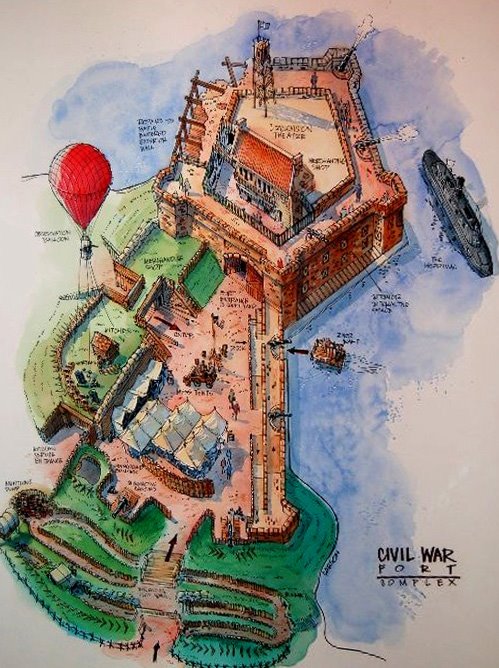

Continuing onward, a large, open field provides room for local Civil War reenactments and other living history demonstrations. Meanwhile, the Civil War Fort (5) jutting out into the artificial Freedom Bay is the park’s Tom Sawyer Island equivalent, inviting us to climb, explore, and imagine what it might’ve been like to be a citizen of a country torn in half. To futher figure it out, the fort itself cleverly houses a 360-degree Circle-Vision film touching on the heartbreak of the Civil War.

The ramparts of the form also provide spectacular views of Freedom Bay, which hosts seafaring battles between the Monitor and Merrimac as a “thrilling nighttime spectacular” in the park’s center.

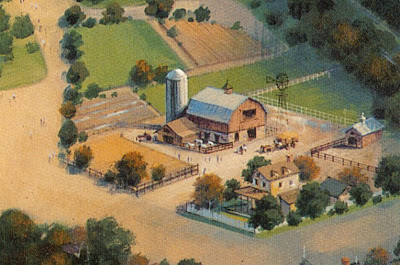

The Eastern half of the park now advances into the 20th century, beginning with the Family Farm (10). Borrowing from Williamsburg, this living exhibition allows you and I to get up close with real farm animals and the tools and instruments used by the Midwest family who lives there. We can also explore their homestead and the acres of gardens and fields surrounding, where real work begets real crops.

And stepping into the shoes of that family, we can imagine the excitement when the State Fair (9) rolls into town just up the path! Recreating a depression-era fair, this land contains a classic, white wooden roller coaster (made of modern steel, but cleverly disguised as a 1930s wooden ride), a Ferris wheel, and a carousel set picturesquely in the dusty cornfields of town. There’s also a real baseball field for exposition games and shows to take place in the land!

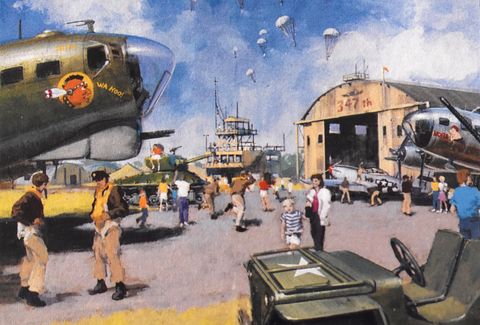

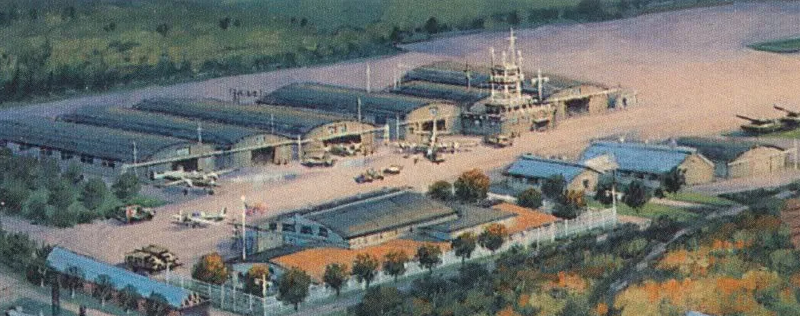

Continuing our counterclockwise journey, we next arrive in Victory Field (8), the sprawling military aviation base showing us the realities faced by servicemen of the Greatest Generation in the lead-up to World War II. In fact, this blacktop runaway would be lined with 1940s airplanes for guests to explore up close.

The land’s headlining attraction, though, would’ve been truly one-of-a-kind, even today. According to industry writer Drew Taylor writing for Collider, Imagineers had used EPCOT Center’s then-new Innoventions to test a radical and evolutionary virtual reality headset that – while rudimentary by today’s standards – would go on to star in Disney’s own Declassified Disaster: DisneyQuest.

But in its most sensational use at Disney’s America, this VR technology would’ve given guests the ultra-personalized, multi-sensory experience storming the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, 1944. Wind; water; harnesses and props… more akin to the Void virtual reality experience (which is cutting edge and inexplicable today, this mid-90s concept was clearly ahead of its time, and would’ve been a spectacular (if immensely low-capacity) component of the park.

Victory Field connects to the next land, Enterprise (7).

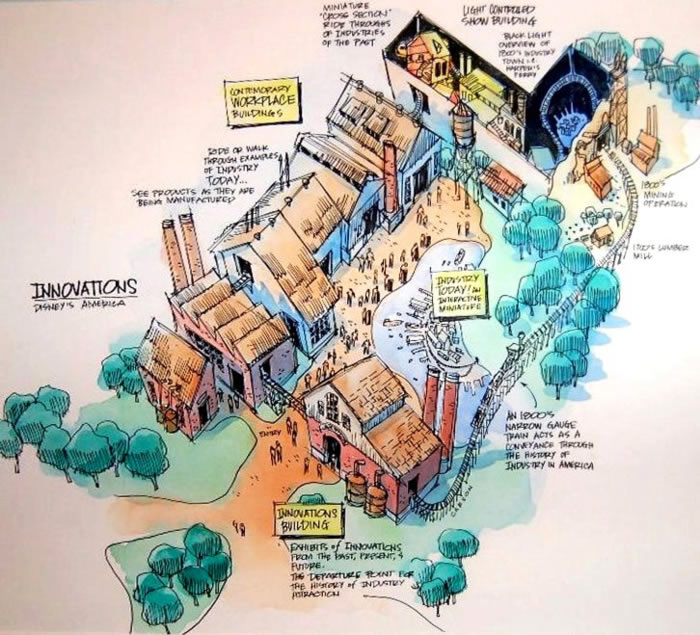

Modeled after an industrial manufacturing town, exhibits on the street level of this land highlight the role of industry in the American story through the 1930s. The land’s signature experience, though, is an indoor/outdoor steel roller coaster whose supports would look right at home in the industrial town, guiding the train up to the second story of the warehouses where riders pass through dark ride scenes.

In a surprising and thrilling finale, this steel coaster – the Industrial Revolution – would dive into a showbuilding, racing between boilers and escaping from the red hot steam of active blast furnaces.

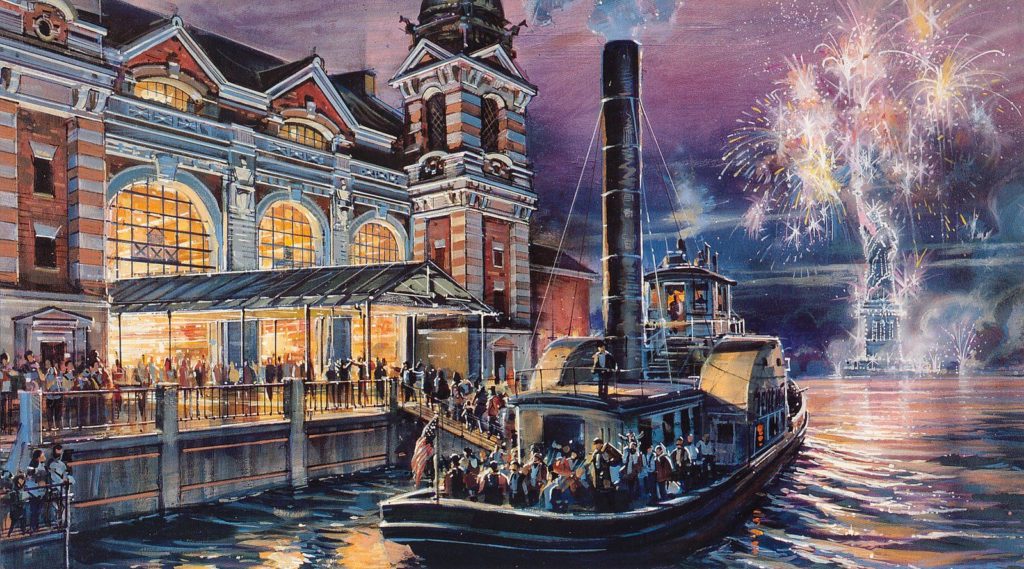

The final land, We The People (6), would theoretically be the park’s most moving. Recreating the French Renaissance-inspired Immigration Building on Ellis Island in New York Harbor, this sensational land would feature exhibits and entertainment celebrating America as a melting pot of languages, cultures, and ideas, allowing guests to have the experience of being immigrants arriving in the land of the free.

Having traveled through time to live our great American story, we find ourselves again returned to Crossroads, U.S.A.

Something different

You can no doubt see that Disney’s America was quite different from anything else Disney had attempted before. The first of a new “regional” park model, Disney’s America would feature only three or four outright rides, relying on entertainment and dining to fuel an experience. And unlike Walt Disney World and the plans underway to transform Disneyland into a multi-day, international destination, Disney’s America was always meant to be a day-trip for D.C. visitors.

A little slower, calmer, and more serious than Disney’s other parks, Disney’s America was something new. But of course, it never came to be… Despite its 1993 announcement and 1998 opening date, problems began to intercept the park’s timeline before a single shovel of dirt was moved… On the next page, we’ll dissect the mounting problems with Disney’s America and Eisner’s last-ditch effort to build in Virginia. Then, on the last page, we’ll see where the “DNA” from Disney’s America was re-used in Disney Parks…