Erosion

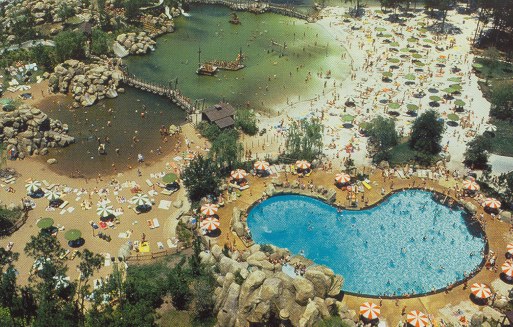

It’s so easy to see what generations of guests loved about River Country; a joyful, playful, ol’ time escape spent leaping off docks, swinging from ropes, and splashing down slides in Florida’s eternal summer sun. It’s almost hard to believe that such a purely good place could exist; such a quaint, charming, hidden gem of a joy right in the massive machinations of Walt Disney World.

Given that, it may be difficult to imagine why the resort’s first water park ultimately closed. Understanding what happened to River Country requires us to leap forward to the New Millennium. Through a modern, 21st century lens, it’s easy to see that a few very important factors led to the park’s decline…

1. Size

At just six acres, the tiny little park wedged between the campground and Bay Lake had extraordinarily limited capacity, even for the early days of Walt Disney World. Guests were often known to arrive at the park shortly after sunrise to find that the park was closed “at capacity” – reportedly, only about 4,000.

Through today’s lens, it’s probably easier to frame River Country as an elaborate, separately-ticketed pool, picnic area, and water playground for Fort Wilderness than a “water park” proper.

That’s made more evident by the lack of practical access to the park in a modern Walt Disney World. Where once the Seven Seas Lagoon had served as the focal centerpiece of Walt Disney World and its hotels and attractions, by the New Millennium, the resort’s gravity had shifted.

So had its transportation system. Unlike 1976 – when guests at either of Disney’s two hotels could take a boat to Fort Wilderness and River Country – by the 2000s, a trip to River Country required a commute. Reaching the park required using internal Disney Transportation including multiple transfers. With its lack of parking, River Country wasn’t a park built for Disney World’s 21st century crowds or touring patterns.

2. Sickness

On August 28, 1980, a wire story from the Associated Press was widely published in American newspapers:

A rare but deadly disease caused by amoeba found in Florida fresh-water lakes has claimed its fourth victim – a New York youngster who spent his vacation swimming at Walt Disney World’s River Country. The disease, amoebic meningoencephalitis, attacks the nervous system and brain, doctors say. It killed two Florida children earlier this month and appears to have been the cause of death of another youngster, a state health official said.

The latest death was that of an 11-year-old boy who visited the Orlando area during the first week of August and swam at the water attraction at Disney World, said Dr. John McGarry, director of the Orange County Health Department.

Both the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the New York Health Department absolved Disney of any wrongdoing since the deadly amoeba in question “can breed in almost any freshwater lake in hot weather.” There were almost certainly no further instances of the amoeba being contracted at River Country since it has a fatality rate of over 95%. Still, the lingering idea of contaminated water culled from Bay Lake must’ve taken some of the fun out of River Country’s ‘natural” setting…

3. Safety

As the first of its kind, evidence of Disneyland’s “naïveté” adds to the park’s charm. At River Country, the “learn as you go” method led to some trouble.

In 1982 – two years after the amoeba-related death of an 11-year old – a 14-year old named Howard Pueppke rode Whoop ‘n Holler Hollow down into Bay Cove, where he drowned. Though Disney’s warning signs had indicated “Rapid Water – Strong Swimmers Only”, the family’s attorneys argued that there were no indications of how deep the water in Bay Cove was at the slide’s exit. Seven years after that, a 13-year old drowned in the park, reportedly in similar circumstances.

It’s not that injury and death are impossible at water parks, but River Country’s may have been avoidable. According to David Koenig’s Realityland, a Disney lifeguard testified that on some days, up to 75 people would need assistance after plunging into the lagoon. Perhaps the untreated lake water, lack of depth markers, and dark, sandy bottom made Bay Cove more difficult to lifeguard than modern, painted pools. (Pueppke’s family was awarded $375,000 in their suit against Disney.)

Though clearly River Country remained open for decades after the three teenage deaths in the ’80s, there’s no doubt that the park lacked the “best practice” signage, pool depths, and planning that are now industry standard. And while the home-spun safety practices of the “wild, wild west” ’70s may have been “good enough” in the ’80s and ’90s, it’s hard to imagine River Country standing up to scrutiny in the modern, litigious age. Especially as growing alternatives offered a much more modern take on the water park concept…

4. Sabotage

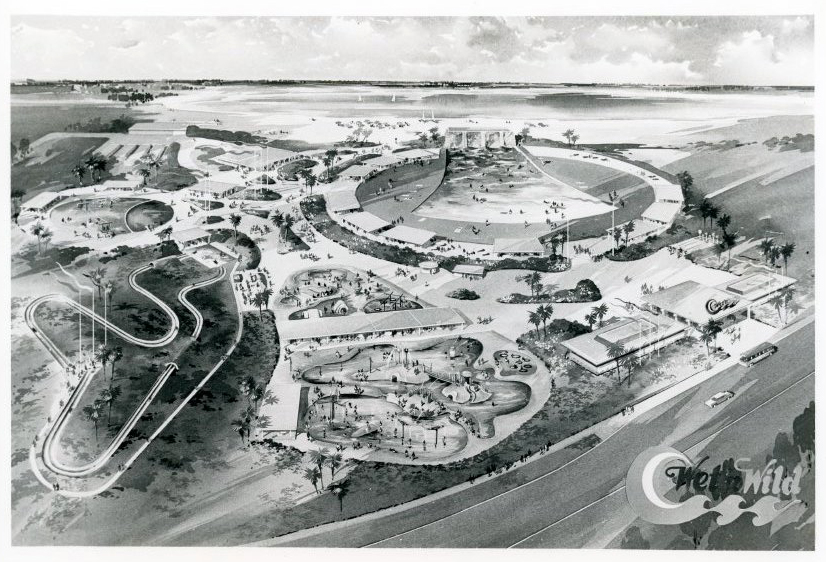

Though River Country’s 1976 debut pretty inarguably made it the first water park, it was 1977’s Wet ‘n Wild down the street that often trumpeted the title. And to Wet ‘n Wild’s credit, it sure looked more like the progenitor of the modern waterpark than River Country did. Conceived by SeaWorld founder George Millay (known as the “father of the water park industry”), the International Drive water park shows just how hot the Central Florida tourism market had become even by the mid-’70s – as if the 1973 oil crisis had been a lifetime earlier.

Remember, too, that in the ’70s, Disney was more apt to embrace competitors as complements, supposing that a rising ride in Orlando would lift all ships. Besides, such (as Jeff Kurtti puts it in Since the World Began) “freeway-adjacent water parks” with “exposed structural supports, impersonal scale, and cold, aquamarine fiberglass structures” were a stark contrast to Disney’s environmental River Country, which Disney imagined would speak for itself as the more quality, enjoyable product.

When Michael Eisner became CEO of Walt Disney Productions in 1984, that view changed. Eisner saw Walt Disney World as an area of unlimited growth potential… if Disney was willing to fight for it, and make some enemies along the way.

With a new vision from the top, the longstanding hotels, attractions, and businesses Disney had viewed as “complements” were recast as “competitors” in a zero sum game. Within a decade of Eisner’s arrival, Disney World had opened a dozen new resort hotels at the “Moderate” and “Value” levels in an effort to reclaim ground lost to “off-site” hoteliers. His Disney had also launched incentives tailor-made to contain guests to Disney property and funded targeted projects meant to crush would-be competitors, like EPCOT’s The Seas to subdue SeaWorld; the Disney-MGM Studios to halt Universal; Pleasure Island to overtake Church Street Station; and of course…

In 1989, Disney officially opened its second water park – Typhoon Lagoon. Combining modern amenities, “next generation” waterslides, a wave pool, a lazy river, heated water, enormous guest capacity, Eisner’s ambitious, expensive, cinematic storytelling and set design that International Drive competitors couldn’t match (and of course, its own gargantuan parking lot), Typhoon Lagoon was a hit.

It was also nearly 20 acres – three times the size of River Country, with capacity and parking for many more guests.

Not coincidentally, in 1989, Goofy (in a turn-of-the-century striped swimsuit) was officially adopted as the mascot of River Country, and daily visits by Disney characters in their ol’ time swimmin’ gear became staples of the parks on summer afternoons. (Chip and Dale were perennial favorites, arriving by boat or even on horseback.)

It was a valiant attempt to keep River Country fresh next to Typhoon Lagoon. It might’ve even helped bolster the park’s appeal for families without thrill seeking teens who turned the newer, bigger park. Even then, more water park capacity was needed to meet the demand of a growing Walt Disney World. Ultimately, Disney sabotaged its own park not once, but twice over.

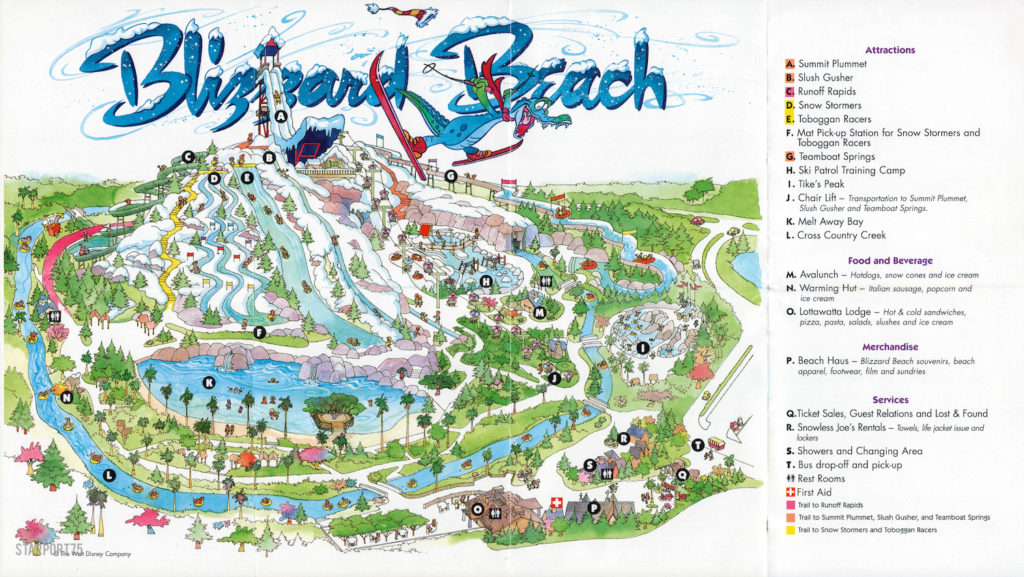

Six years later in 1995, Disney debuted a third water park, Blizzard Beach. At 26 acres, Blizzard Beach offered even more space, more capacity, and more attractions.

(Side note: True to Eisner’s ethos, Typhoon Lagoon and Blizzard Beach are often cited as the leading cause of Wet ‘n Wild’s demise. Millay sold all 10 Wet ‘n Wild’s when he retired in 1998, with nearby Universal Orlando snapping up the original in Orlando. Universal operated the park until December 31, 2016 when it was closed for good. The next summer, Universal’s Volcano Bay opened as a spiritual successor, but branded, built from-scratch, and actually located on Universal’s campus. Wet ‘n Wild was demolished and today Universal’s Endless Summer Resort – Surfside Inn occupies its lakefront location.)

With Typhoon Lagoon and Blizzard Beach thrilling guests of the ’90s, Disney World had outgrown River Country. It’s almost incredible to imagine that for at least a few years, River Country – with its ’70s swimming hole aesthetic, limited capacity, lake water, and old fashioned attractions, co-existed with two ultra-modern and much, much larger water parks. But there’s probably one factor that led to the definitive end of River Country above any other…

5. September 11

In many ways, a shared national crisis of the 1973 oil embargo was the spark that created River Country. Then nearly thirty years later, another national crisis spelled its end.

The September 11, 2001 attacks on New York City brought the entire world to a shuddering halt, and interest in tourism and air travel fell to never-before-imagined lows. Across the theme park industry, a massive financial collapse and skittish projections for a rebound saw the end of incalculable projects and expansions.

In the wake of September 11th, Walt Disney World mothballed entire hotels, projecting years of catastrophically low attendance, reduced budgets, and cancelled vacations. (Only 2005’s “Happiest Homecoming on Earth” successfully re-sparked Disney’s investment in its parks, launching the modern era of Annual Passes, “lifestyling,” and online obsession.)

It made sense to close River Country in fall 2001 – just ahead of its typical off-season refurbishment during Florida’s chillier months. But instead of re-opening in Spring 2002 as expected, River Country… didn’t.

River’s End

On April 11 2002 – six months after its seasonal closure – the Orlando Sentinel reported that “Walt Disney World’s first water park, River Country, has closed and may not reopen. […] Disney World spokesman Bill Warren said that River Country could be reopened if ‘there’s enough guest demand.’”

But of course, in light of the park’s size, competition from Typhoon Lagoon and Blizzard Beach, and the downturn in tourism, that demand never came. Summer after summer, River Country remained standing but not operating, its rocky peaks and lake water lagoon visible on the shores of Bay Lake for anyone who bothered to look. A “temporary” closure lasting months or even years isn’t unheard of in extreme circumstances (see, 2020)… But especially in the ’90s and 2000s, those “temporary” closures sometimes ended up not being so “temporary” at all.

So it wasn’t tremendously surprising when, in 2005, Disney officially fessed up that River Country was closed for good. Long-since surpassed by bigger, bolder, and more ambitious water parks – and four years after its “temporary” closure – Fort Wilderness’ little willow grove with its splashy swimmin’ hole would never re-open. But the weirdest thing about River Country isn’t that it closed… it’s what happened afterward.