Snow White’s Scary Adventures may not technically have been an Opening Day Original at Magic Kingdom (thanks to its much, much scarier predecessor being an altogether different ride), but for a generation of Millennials, it might as well have been! More frightening than standard Fantasyland fare, this harrowing race through wicked woods, stormy cliffs, and spooky dungeons may have added yodeling Dwarves and wishing wells, but it was – fundamentally – a rare Magic Kingdom fright.

So how could a 21st century surge in Snow White’s popularity and profitability result in the closure of the Magic Kingdom classic dedicated to the character? As tends to be the case in our Lost Legends, a swirling vortex of chance occurences and falling dominoes all seemed to coalesce…

1. “Royal Revenue”

1937’s Snow White wasn’t just the first full-length animated feature film ever… it was also the birth of the Disney Princess. It’s because of Snow White that Walt Disney’s fairytale adaptations became his signature stories, followed by Cinderella (1950) and Sleeping Beauty (1959) in the decades that followed – together, a sort of royal trifecta.

And in fact, as animation fans will tell you, it wasn’t really until Disney’s return to crafting the definitive versions of fairytale stories that the company reached its second peak: the Disney Renaissance. Beginning with 1989’s The Little Mermaid, Disney’s unlikely return to prominence after decades of stagnation rested on modern tellings of classic tales and the heroes (more often, Princesses) who brought them to life.

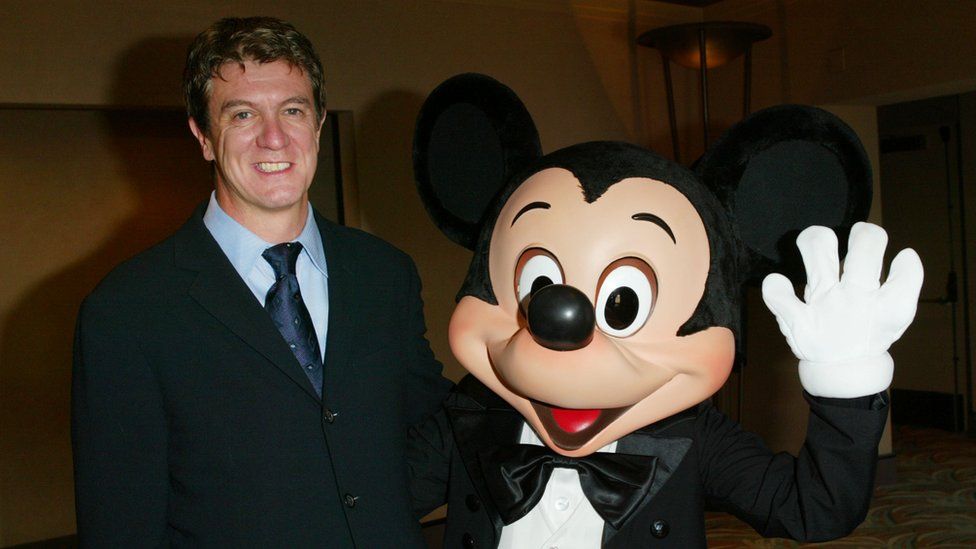

In 1999, former Nike executive Andy Mooney arrived at the Walt Disney Company as head of Disney Consumer Products – the brach of the company responsible for, among other things, merchandising, character licensing, and the Disney Store.

You have to imagine that at the dawn of the New Millennium, the Walt Disney Company was a very different place than it was a decade before or a decade after. After the Disney Renaissance but before Disney’s 21st century acquisitions of Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm, Mooney was responsible for elevating Disney’s products and licensing to the next level, and he quickly stumbled on a candidate. As the story goes, Mooney was standing in line for a Disney on Ice show in Phoenix, Arizona when he had a billion-dollar idea. He told The New York Times:

“I was surrounded by little girls dressed head to toe as princesses… They weren’t even Disney products. They were generic princess products they’d appended to a Halloween costume. And the light bulb went off. Clearly, there was latent demand here. So the next morning I said to my team, ‘O.K., let’s establish standards and a color palette and talk to licensees and get as much product out there as we possibly can that allows these girls to do what they’re doing anyway: projecting themselves into the characters from the classic movies.'”

While some at Disney (including board member and head of Feature Animation Roy E. Disney) objected to the notion – insisting that Disney had always “avoided mingling characters from its classic fairy tales in other narratives, worrying that it would weaken the individual mythologies” – Mooney pushed forward with elevating Disney’s disconnected fairytale royals into a single brand and product line. The Disney Princess franchise was born.

Initially comprised of classic princesses like Snow White, Cinderella, and Aurora co-mingling with Renaissance counterparts Ariel, Belle, Jasmine, Pocahontas, and Mulan, the Princess franchise was launched in 2000 with practically zero marketing, but plenty of dolls, costumes, and licensing deals.

In its first year, the franchise earned a respectable $300 million. Today, just 20 years later, the franchise has reportedly earned upwards of $46 billion (nearly $3 billion a year on average), making it the 7th highest earning media franchise of all time, especially relative to its young age. (For comparison, the Star Wars franchise has earned a cumulative $70 billion since 1977).

The “invention” of the official Disney Princess might seem like something that would only ensure the survival of Snow White’s Scary Adventures, not lead to its closure! But of course, nothing happens in a vacuum… Bear with us as we jump to the second major domino en route to the ride’s end.

2. “Potter Pressure”

Right as the Disney Princess line was ascending in the early 2000s, Disney found itself in a position it had never been in before: playing catch-up. Don’t misunderstand: Disney has been forced to the mat before. They’d handily matched the opening of Universal Studios Florida back in 1990 with a clever counterstrike (the Disney-MGM Studios). A decade later, Disney had prepared for war once again as Universal’s Islands of Adventure loomed (even if most of the retaliatory rides they’d drafted went unbuilt; a murkey marketing campaign sunk Islands’ initial success, leaving Disney comfortably in control of Central Florida).

But in May 2007, Universal came clean. After years of negotiations (including, reportedly, with Disney), J. K. Rowling and Warner Bros. had agreed to license one of the most iconic brands of all time – Harry Potter – to Universal Parks & Resorts. In an era before the “IP Wars” and the mega-acquisitions we know today, Universal had an almost-unbeatable pop culture coup. There was no denying it this time: the Wizarding World of Harry Potter was going to change the dynamics in Orlando.

And frankly, it would change the dynamics in all of themed entertainment design, too. When Hogsmeade opened in 2010, Disney executives reportedly looked on in stunned awe as people queued for hours, waiting in packed lines not to get onto rides, but to get into gift shops. People were tripping over themselves to buy $45 wands, and $5 cups of “Butterbeer,” and $10 chocolate frogs. and $100 House robes. Universal hadn’t built a ride; they’d built a world… One that guests wanted badly to inhabit.

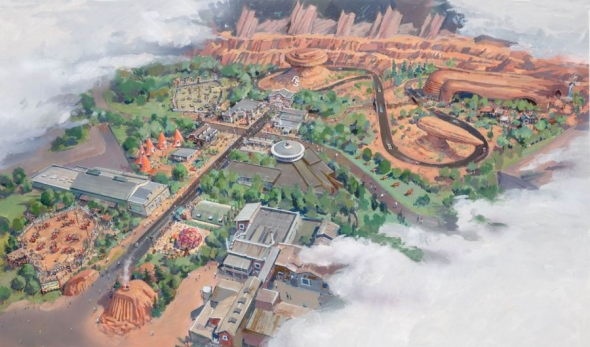

The “living land” was born. Following Universal’s lead(!), Disney announced plans for their own totally-immersive land plucked from the screen and built to hyper-fixated realistic scale: Cars Land, to anchor a billion-dollar rebirth of Disney California Adventure.

Today, it’s obvious that the “Wizarding World” model has become the de facto one, with the idea of ultra-immersive expanded worlds of original mythologies, must-try dining, and in-universe souvenirs powering (to varying degrees) Toy Story Land, Springfield U.S.A., Diagon Alley, Avengers Campus, Pandora: The World of Avatar, Super Nintendo World, Frozen-themed lands, and Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge.

But before any of those, we’d meet our third domino…

3. Finalizing Fantasyland

In 2009, then-Chairman of Disney Parks Jay Rasulo came on stage at the semi-annual D23 Expo to announce a “living land” that would take shape just a few miles from Hogsmeade. At last, Magic Kingdom would dispense with its own Medieval tournament-tent style as Disneyland had done three decades before and construct a 21st century New Fantasyland.

Given that the Disney Princess franchise has averaged well over $2 billion in revenue per year since its inception (versus Potter’s $1.4 billion per year average), it stood well within reason that Andy Mooney’s mega-franchise had earned its own expansion at Walt Disney World… and could even be Disney World’s “Potter swatter.”

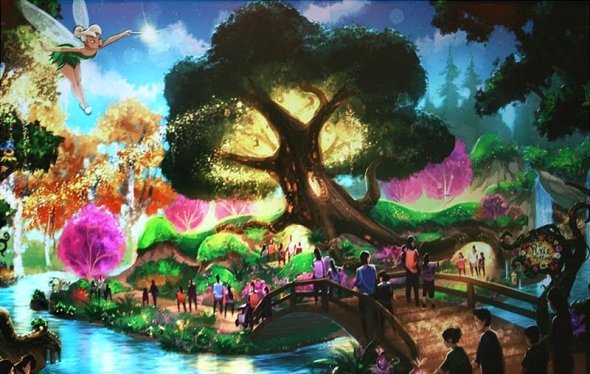

In true Wizarding World style, Rasulo’s land – with immersive mini-areas dedicated to Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid, and the up-and-coming Fairies franchise – would offer in-universe shopping and dining galore.

However… As fans studied the artwork Disney released (as you can, by clicking and expanding the concept art above to see tremendous detail), they quickly noticed that the land’s audience demographic was bit skewed. Why? Well, consider the things that guests would’ve found to do in this expansion:

- The starring Be Our Guest Restaurant serving as the land’s must-see attraction;

- A next-generation play-and-greet / elaborate walkthrough attraction with Belle from Beauty and the Beast inside her father’s cottage;

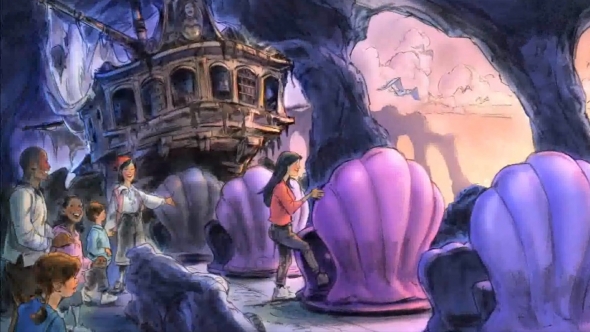

- A play-and-greet with Ariel from The Little Mermaid;

- A play-and-greet with Cinderella inside her stepmother’s Chateau;

- A play-and-greet with Tinkerbell inside an elaborate Pixie Hollow area borrowed from Disneyland, replacing Mickey’s Toontown Fair entirely;

- Play-and-greets with Snow White and Aurora in their own dedicated cottages;

- A relocated and enhanced Dumbo the Flying Elephant;

- A new dark ride based on The Little Mermaid, duplicated from the one being built at Disney California Adventure

To fans’ count, this brand-new, much-anticipated expansion – “the largest in Magic Kingdom’s history” – amounted to six elaborate meet-and-greets with Disney princesses… and just one new ride. Was this the “Potter swatter” discussion boards had prophesised for years? A land that looked lovely, sold expensive food, and had six meet-and-greets? But wait…

In late 2009, then-CEO Bob Iger announced a major shakeup at the Walt Disney Company. Jay Rasulo was moved out of the Parks division and became Disney’s CFO overseeing finances, swapping roles with Tom Staggs. (The move was largely seen as a way for Iger to balance out the candidates’ respective portfolios ahead of his presumed selection of one of them to be his own replacement of CEO.) The incoming Staggs allegedly took the New Fantasyland plans home to his preteen sons who – predictably – didn’t show much interest.

So when Staggs appeared at the next D23 Expo in 2011, it was with a revised New Fantasyland to present. While areas dedicated to Beauty and the Beast and The Little Mermaid would remain, the rest of the land had evolved. The Fairies franchise and its Pixie Hollow had been axed in favor of a more budget-friendly Storybook Circus reimagining of the Lost Legend: Mickey’s Toontown Fair.

And that central plot of land – where once Cinderella’s Chateau, Aurora’s Cottage, and their associated play-and-greets would’ve been been housed – became something new entirely. A new family roller coaster called Seven Dwarfs Mine Train would come to life, rollicking, swinging, swaying, and slaloming along forested hills in and around the gem mine from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train wouldn’t just provide New Fantasyland with a new, thrilling anchor attraction that could come online quickly and inexpensively; it would at help balance the expansion by only tangentially tying to the Disney Princess franchise.

Of course, Seven Dwarfs Mine Train hadn’t just solved a problem; it had created one, too. For one, it would make Snow White’s Scary Adventures oddly redundant, with two retellings of the same story set next to one another. Second (and most importantly), the new Mine Train would effectively evict Disney Princesses from their custom-made meet-and-greets…

Staggs might not have lost any sleep over evicting two 1950s princesses from valuable Magic Kingdom acreage, but his time as CFO had assured him that a new generation of Princesses was on the rise: 2009’s Tiana, 2010’s Rapunzel, and early rumblings of a Snow Queen signaled that the era of Disney Princesses was far from over, and a flex space to welcome those new royals would be needed. Now, they’d just need consolidated into the announced Princess Fairytale Hall. And fans knew what that meant…