“In the beginning…!”

Though it may not be the prologue you’d expect from a trip down an amusement park’s memory lane, there’s no better (nor more biblical) a way to begin an exploration into one of the most unique and under-recognized attractions on Earth – a last-of-its-kind, historic whale of a walkthrough found only at Kennywood Park just outside of Pittsburgh…

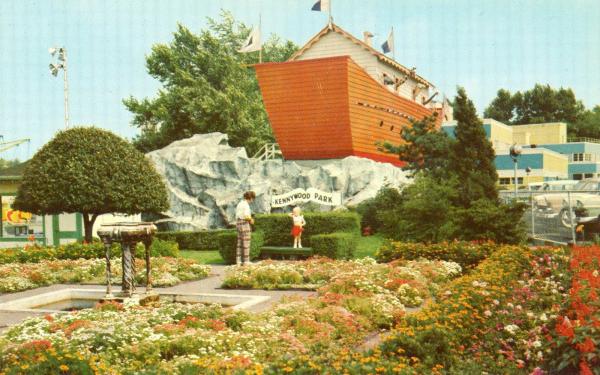

A classic attraction that’s survived the Great Depression, a World War, fifteen Presidents, countless redesigns, and (imagine this) a real flood, Noah’s Ark at Kennywood has been shared between nearly 90 years of Yinzers. Like a story passed from generation to generation, this heart-warming walkthrough still floats on today, forever stranded atop a rocky plinth smack dab in the heart of “America’s Finest Traditional Amusement Park.”

There’s something hypnotic about Noah’s Ark, gently rocking to and fro, its bow and stern rising and falling in sequence, its whistle sounding across the midway – “Heeeeeeee… Hoooooooo….”

To step aboard this 1936 attraction is to travel through time and emerge in a simpler era when funhouses dominated midways and trolley parks were the talk of the town. Instantly charming, retro-cool, and delightfully disorienting, the single, remaining Ark may seem an oddly aged attraction to stand among our Modern Marvels collection, but like all the rides we chronicled there, it’s secret to success can only be told by setting sail through its story…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access 100+ interconnected Extra Features, and receive a Member card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this in-depth, ad-free theme park history project for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

Kenny’s Grove

Like so many of the amusement parks, attractions, and midways that dotted the American landscape throughout the early 20th century, the story of Kennywood is one of chance.

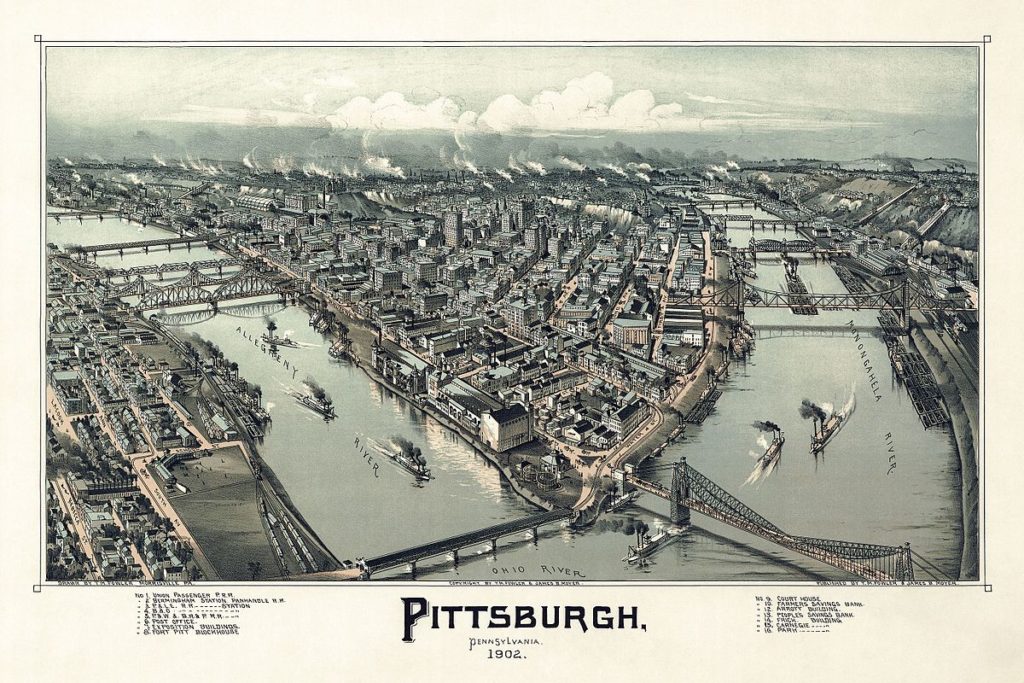

When Thomas Kenny set out westward in the early 1800s as part of the country’s push for expansion, he happened upon an unoccupied, forested bluff overlooking the Monongahela River just southeast of its confluence with the Ohio River. The site of 1755’s Battle of the Monongahela (in which a young George Washington had served as colonel, above), Kenny claimed the 365-acre wooded property as an ideal farm and homestead.

By the end of the 1800s, Pittsburgh had grown into a rapidly-industrializing city powered by the Carnegie Steel Company. Towers billowing steam and soot littered the city’s skyline. Boats raced railroad lines that were stitched along the city’s “Three Rivers,” carrying raw materials into and out of the “Steel City.” A city of industry and immigrants; smokestacks and steel mills, Pittsburgh would soon become the eighth largest city in the nation.

In this expanding, urbanizing, and quickly-crowding city, opportunities to escape to nature were increasingly rare… but given that the property claimed by their ancestors was far too large to fully utilize, the Kenny family opened a portion of their wooded real estate to the public as a picnic park. “Kenny’s Grove” was born.

In 1898, Kenny’s Grove was leased to the Monongahela Street Railways Company – proprietor of Pittsburgh’s new, electric-powered, intra-city trolley system. In fact, across the country, such transit companies sought to extend their service lines out of town and toward pastoral picnic parks – offering leisure and amusement to factory workers and their families… while also cleverly driving up weekend trolley ridership.

In that way, the little park overlooking the Monongahela isn’t so different from any one of the hundreds of “trolley parks” that bloomed across the United States in the early 1900s. Accessible by rail, parks like Kennywood grew organically over decades, one step at a time.

Like its contemporaries, Kenny’s Grove was soon home to a carousel, a casino hall, a bandstand, a lagoon with rentable rowboats, and a dance pavilion (with many of those structures remaining today) – a one-stop shop for Victorian entertainment.

Fun in the Dark

In 1901 – 120 years ago! – Kennywood added its first dark ride: The Old Mill (above). Drifting down a flume channel powered by a spinning waterwheel, riders would pass through simple scenes depicting grottos and caverns underscored by recordings of orchestral music. Whether “Old Mills,” “River Caves” or “Tunnels of Love,” these water-powered attractions were the first in a genre today called “dark rides.”

For couples, the draw of these early, rudimentary dark rides was the chance to canoodle in the dark – a rare opportunity in the prudish Victorian era. For most people, though, the Old Mill’s real draw was the ability to see those interior scenes lit by the breathtaking, new electric lightbulb. (Restored and reimagined in 2020, The Old Mill remains the world’s oldest operating dark ride today.)

Though no one alive today would remember it, DAFE – the Darkride and Funhouse Enthusiasts organization – believes that in 1902, the park opened an attraction called the “Pavilion of Fun.” Within, guests could walk through the blustery “Cave of the Winds” (where surprise compressed air streams would send women’s skirts flying and men chasing after hats) and the “Earthquake Room” (with wooden floors trembling, rumbling, and shaking).

They’d find relief at the “Spring Water” oasis… only to find that connecting the fountain’s tin cup with a secretly-electrified stream of water caused a “shocking” surprise. (It was, to say the least, a very different time… as also evidenced by a peep hole through which guests would see a reflection of their own face on the body of “a fat policeman making love to the house-maid.”)

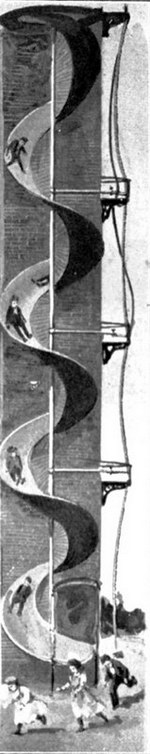

Finally, guests would climb “The Crazy Staircase” (with steps rising and lowering opposite one another, patented by Coney Island’s George Tilyou) for a ride down the “Swirly Slide.”

Suffice it to say that Kennywood’s “Pavilion of Fun” would today easily be recognized as one of the first ever in a legitimately new genre of attractions: a funhouse! Evolving parallel to the first walkthrough attractions in New York’s Coney Island, Kennywood added a handful of amusing funhouses in the era: the endless mazes of the House of Trouble; the Laughing Gallery mirror maze (the first-of-its-kind, imported from the Paris Exposition); The House of Mystery (ironically, for which no known images or descriptions remain); and the Daffy Dilla Fun Factory (featuring a human roulette wheel!).

One after another, Kennywood refined the art of the laugh-out-loud walkthrough in subsequent installations and redecoratings… The Tumble Inn; Hilarity Hall; the Bug House; Tut’s Tomb (capitalizing on the actual 1922 archaeological discovery, in real time)… You have to imagine that even by the 1920s, funhouses, slides, and walkthroughs still vastly outnumbered even the most traditional dark rides. (The definitive, single-rail, bus-bar powered “Pretzel” dark ride wouldn’t even be patented till the end of the decade.)

While meandering Old Mills and Tunnels of Love may have given guests respite from the summer heat in darkened, musty chambers, walkthroughs were the way that guests could step into new worlds, filled with special effects, laugh-out-loud tricks, and (sometimes literally) shocking surprises. (It’s probably no coincidence that even with the cart-based dark ride at his disposal, Walt Disney himself initially envisioned both the Haunted Mansion and Pirates of the Caribbean as walkthroughs!)

But the most unique subgenre of funhouse was soon to arrive…