Let’s stop for just a second to take a step back and see the bigger picture. Disney and Pixar had officially extended their three-film agreement to six, ensuring their distribution partnership to 2006. But internally, tensions were beginning to boil.

(Pixar) Peaks and (Disney) valleys

Tarzan’s 1999 release is commonly understood as the definitive end of Disney’s second Golden Age, and in retrospect, we can easily see the early 2000s as a period of decline at Disney Animation… Dinosaur, The Emperor’s New Groove, Atlantis, Lilo & Stitch, Treasure Planet, Brother Bear, Home on the Range, Meet the Robinsons…

Put simply, by the 2000s, Disney’s Renaissance winning streak was definitely over. In an unfortunate replay of the ’70s, the studio seemed to stumble with every release, consistently losing out at the box office and with critics. In an almost perverse antithesis of the ’90s Renaissance, Disney in the 2000s was a studio in decline once more.

Worse, while Disney was releasing half-hearted and forgettable films and focusing on inexpensive direct-to-video sequels, new competitors were arising… When Eisner refused to promote Jeffrey Katzenberg after the death of Frank Wells, Katzenberg left in disgust and started his own animation studio – DreamWorks SKG.

DreamWorks burst onto the scene with 2001’s Shrek, which ran away with $487 million at the box office, skewering Disney all the way to the bank. Via DreamWorks, it was clear that computer animation was more than just a passing fad… and more to the point, thanks to the emerging artform, Disney would never be alone in the animation game ever again.

The ingredients were set: another Disney decline; a new, emerging CGI animation market; and, for Pixar, a near perfect track record for box office blockbusters, critically-acclaimed films, and beloved, heart-wrenching, global phenomenon films. It stood to reason that not only could Pixar go on without Disney, Pixar could be the new Disney.

Both Michael Eisner and Steve Jobs were (of course) deeply competitive and invested business people who were (deservedly) fiercely protective of their products, so it’s no surprise that Jobs was willing to renegotiate for a new contract with Disney… but only with some new terms. For example, Jobs wanted Pixar to retain creative control of its franchises going forward, and wanted to retroactively regain full control of Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, and Monsters Inc., too.

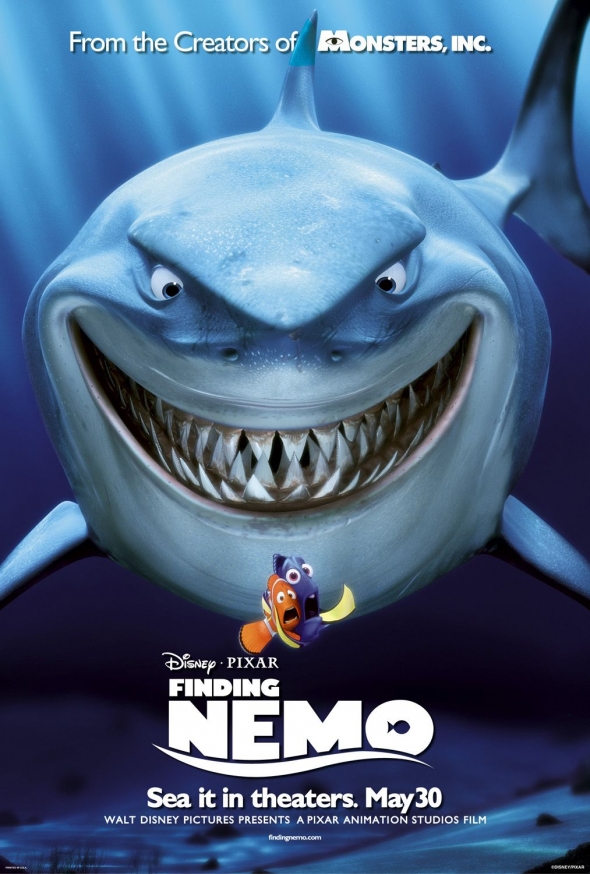

As tensions grew, a fourth Disney•Pixar release – Finding Nemo – was mere months away from release. Inside the company, Eisner allegedly began expressing to his staff that Finding Nemo wasn’t going to be a hit. He hadn’t liked early cuts he’d seen of it, and, according to the LA Times, began to suggest to his team that it wouldn’t be such a bad thing to have Nemo fail; that it would give Steve Jobs “a reality check.”

… But Finding Nemo – Pixar’s fourth original film – earned $940 million at the box office, becoming the highest grossing animated film ever. Pixar hadn’t just proven itself… it had broken Disney’s own record. In one bite, Disney’s leverage was sunk.

Just like that, it was official: on January 30, 2004, Disney and Pixar announced that they could not come to a new distribution agreement and would officially cut ties. While two remaining films – Cars and The Incredibles – would be delivered by Pixar and distributed by Disney, Pixar was an independent studio with no distribution deals – and free to find a new partner – post-2006. More of a battle of CEO egos than numbers, the two companies parted ways. Of course, that’s not quite the end…

Save Disney?

In 2004 – right after the impending split between Disney and Pixar was made public, Disney announced a new division of its animation studio: Circle 7 Animation. This new arm of Disney’s filmmaking business would specialize in computer-generated animation. Coincidence? Of course not.

While it’s hard to imagine today, sincere plans were made to release sequels to the six Disney•Pixar stories (Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, Monsters Inc., Finding Nemo, Cars, and The Incredibles) without Pixar’s team involved at all. While Pixar would go on to create and release new films of its own (perhaps as Paramount•Pixar or Sony•Pixar), Disney alone would control the fate of the six original films as franchises, simply paying Pixar a small fee.

Circle 7 started right out the gate with three films on its docket: Toy Story 3, Monsters Inc. 2: Lost in Scaradise, and Finding Nemo 2.

However, in 2003, our old friend Roy E. Disney returned. Almost exactly thirty years after leading a charge to hire Eisner as CEO, Walt’s nephew came back calling for his resignation. Roy himself resigned from his position on Disney’s Board of Trustees and initiated the “Save Disney” campaign, calling out Eisner for his micromanagement at the studio that had led to all those box office flops in the early 2000s; for cutting costs at the Disney theme parks to never-before-seen lows; for turning Disney into a “rapacious, soulless” company.

In March 2005 – a year before his contract was set to expire – Eisner stepped down from his position as CEO. (Eisner even allegedly declined his contractual rights to keep an office at Disney’s headquarters and use the company’s private jet – evidence of how frosty the relationship was.) His President and COO, Bob Iger, stepped into the CEO role.

The story goes that when Bob Iger attended the opening of Hong Kong Disneyland in 2005, he staked out a spot to watch the celebratory parade that marched down Main Street and – to his surprise – found that the newest Disney characters in the parade were from movies that were at least 10 years old, whereas the “new” generation of characters recieving the most applause from the crowd were exclusively Pixar characters. That’s all the proof he needed to start his financial executives exploring… beginning with some sincere, heart-to-heart conversations between Iger and Steve Jobs himself.

On May 5, 2006 – two years after Disney and Pixar had decreed their impending divorce – Disney announced that it would purchase Pixar outright for $7.4 billion, all stock. Steve Jobs (who owned 49.65% of Pixar) would be catapulted to Disney’s largest shareholder with a 7% share – worth nearly $3.9 billion – and a seat on the Board of Directors.

The Pixar Push

In 2006, it became official. For more than $7 billion (nearly what Disney paid for Marvel and Lucasfilm some years later combined), Disney acquired Pixar outright. Pixar Animation Studios and Walt Disney Animation Studios were now partners under the same umbrella, though they would retain their individual identities. Disney• Pixar would become a permanent brand mark beginning with 2006’s Cars.

(Circle 7 Animation was dissolved, of course, without ever having created a film. 80% of its animators were transferred to Walt Disney Animation. Pixar showrunners intentionally chose not to look at Circle 7’s script treatments for a third Toy Story, Monsters Inc. 2, or Finding Nemo 2 when they created Toy Story 3, Monsters University, and Finding Dory.)

Now, Pixar was Disney. Disney owned Pixar. And that meant that Pixar’s place in the parks could expand… Read on…