L – Lost Weekend

Walt’s plans for a “family fun park” initially revolved around what he called “Mickey Mouse Park” – a recreation facility he planned to built on a vacant lot adjacent to the studio building in Burbank. Even though “Mickey Mouse Park” never came to be, you can see the early DNA of Disneyland in the plans for it – a turn-of-the-century town square, a Western village, even a steamboat that would circumnavigate an island – just like the Rivers of America in the final Disneyland.

In 1952, Walt founded a new company – WED Enterprises (see, “W”) – to begin work on the park in earnest. To jumpstart the endeavor, Walt had mortgaged his home and life insurance policy… but WED Enterprises was hemorrhaging money. Walt’s financially-minded business partner and brother, Roy Disney, reluctantly agreed to secure meetings with banks in New York to try to sell them on providing WED with a cash infusion.

But Walt needed collateral to convince the businessmen there. He called up a trusted friend and animator named Herb Ryman who’d worked for the studio in the ’40s and asked him how long it would take him to drive to the Disney lot. Ryman said fifteen minutes if he came as he was, a half-hour if he dressed. Walt told him to come as he was and Walt would meet him at the studio gate. According to biographer Bob Thomas’s account in Walt Disney: An American Original, the conversation between the two when Ryman arrived went something like:

“Herbie, we’re going to build an amusement park.”

“That’s interesting. Where are you going to build it?”

“Well, we were going to do it across the street, but now it’s gotten too big.”

“What are you going to call it?”

“Disneyland.”

“That’s as good as anything.”

“Look, Herbie, my brother Roy is going to New York Monday to line up financing for the park. I’ve got to give him plans of what we’re going to do. Those businessmen don’t listen to talk, you know; you’ve got to show them what you’re going to do.”

“Well, where is the drawing? I’d like to see it.”

“You’re going to make it.”

“No I’m not! This is the first I ever heard about this. You’d better forget it. I’ll embarrass both you and me. I’m not going to make a fool of either one of us.”

Walt reportedly pleaded, “Herbie, this is my dream. I’ve wanted this for years and I need your help. You’re the only one who can do it. I’ll stay here with you and we’ll do it together.”

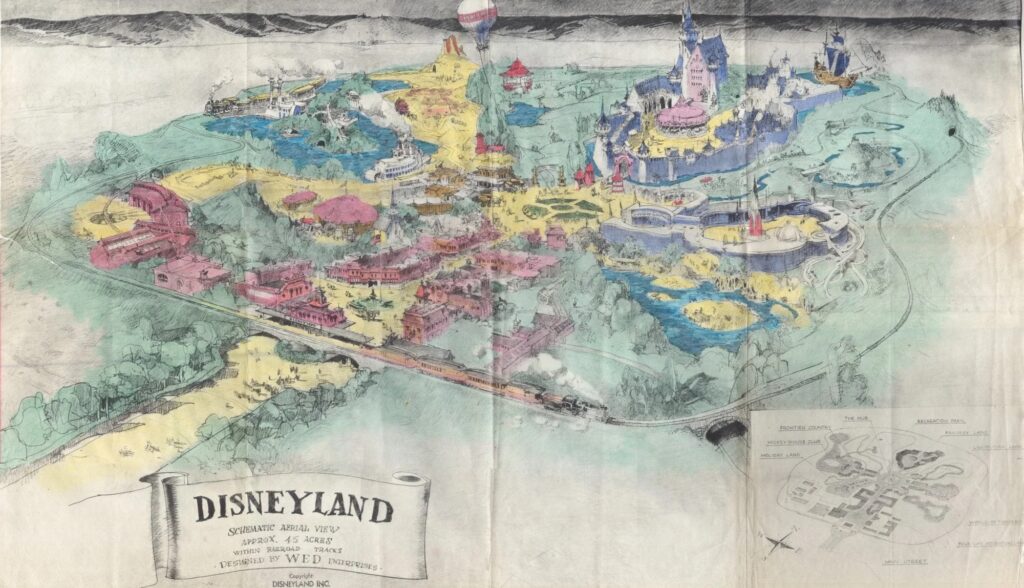

Walt and Herb spent a full, sleepless Saturday and Sunday (what’s now called the “Lost Weekend”) working together as Walt slowly spoke through every corner of the park he envisioned in his mind. It’s worth it to click and expand the image above to see the details of the “Lost Weekend” drawing up close. It really does capture the basic framework of Disneyland (including, as you’ll see on the inset, the “hub-and-spokes” layout).

When Roy returned to the studio on Monday, Walt and Herb looked “worse for the wear,” but the drawing was complete. Roy used it to secure financing for the park, and ground was broken on Disneyland nine months later. The “Lost Weekend” drawing, by the way, was sold at auction in 2017 for $700,000.

M – Main Street, U.S.A.

Walt Disney – the youngest son of Elias and Flora Disney – was born in 1901 in Chicago, but raised in the small town of Marceline, Missouri. In a letter home to the Marceline News in 1938, the 37 year old Walt wrote:

“More things of importance happened to me in Marceline than have happened since or are likely to in the future. Things, I mean, like experiencing my first country life, seeing my first circus parade, attending my first school, seeing my first motion picture! I know you’ll agree with me that such childhood ‘firsts’ as those are of utmost importance in any human being’s life.”

Walt was fascinated with progress. There’s a reason that his dedication for Disneyland called on the park to be a place where “age can relive fond memories of the past, and youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future.” That makes it fitting that the entrance to Disneyland is Main Street, U.S.A. Disney trivia will often say that Main Street is a recreation of Marceline as Walt remembered it. Of course, that’s not necessarily true, even if Walt’s rosy recollection of his forever-hometown probably did serve as a basis.

Main Street is forever locked to the turn-of-the-20th-century. That’s on purpose, too. Walt liked that his childhood was a time of transition – when gas streetlamps and the brand new incandescent lightbulb co-existed; when you’d find both horse-drawn carriages and automobiles passing through town. Main Street is that optimism incarnate – a celebration of a simpler time in the past, sure, but more to the point, a time capsule of that era when anything seemed possible in the future.

It also establishes one of the most essential elements of Disneyland. Main Street doesn’t recreate a real place. You couldn’t find it on a map, or pin it on a timeline. That’s the point. Disneyland’s foundational ethos is romanticism; idealization. There was never a real town that looked like Main Street, U.S.A. does… yet Main Street brings to life our shared vision of what life in the turn of the century was like! Scholars say that Disneyland invented a new kind of architecture called “the architecture of reassurance.” This is a place that’s part historic and reverent, but romanticized and passed through a lens of nostalgia. And by the way, so it goes for Frontierland, Adventureland, New Orleans Square, etc. Though they resemble our real world, they’re the reassuring

N – Nighttime Spectacular

The first regularly-scheduled fireworks show at Disneyland took place in 1958 – three years after the park opened. Fireworks have continued to be a part of Disneyland’s DNA ever since. But fireworks aren’t all that Disney Parks offer after dark. It’s often said that every Disney Park comes alive after sunset, becoming more beautiful than ever. But another spectacular transformation occurs at night too: “Nighttime Spectaculars” emerge. Far more than “just” fireworks, Disney Parks’ Nighttime Spectaculars are magnificently-scaled after dark extravaganzas that are jaw-dropping and stunning in their scale and execution.

Since 1992, Disneyland Park has been home to Fantasmic! (If you’ve never seen it, don’t spoil it, but if you have, dive deep into the show in our Modern Marvels: Fantasmic! feature.) Unfolding from nothing, the show takes place in Mickey’s imagination, beginning the instant he falls asleep. He speaks just two (infinitely memorable) lines during the entire twenty minute show. Otherwise, Fantasmic is a swirling descent into Disney animation as Mickey is tempted by the Magic Mirror to cross the line from dream to nightmare. A jaw-dropping, all-time classic, Fantasmic! is an unbelievable E-Ticket in its own right.

As part of its five-year, billion-dollar reimagining, Disney California Adventure received its own nighttime spectacular, World of Color. Taking place on Paradise Bay, World of Color is meant to connect to the long-running television program hosted by Walt himself of the same name (and in fact, the original version of the show beautifully reprises the iconic theme song of that television show). World of Color is a celebration of Disney and Pixar animation, brought to life through water, fire, and projection.

Unfortunately, the show’s inherent flexibility often sees it turned over to whatever promotional celebration Disney Parks are in the midst of. For the “Disney100” celebration, a new show called “World of Color – One” was installed. Instead of the classic “World of Color” anthem, it uses a new song called “Start a Wave” to convey the show’s central message – that anyone can be the one to make a difference. (A theme that just so happens to be embodied by just about every Disney + Pixar + Marvel + Star Wars hero – ideal for studio cross-promotion!) That makes World of Color – One a far less subtle, creative, emotional, and compelling show than the original version, instead mashing together clips of recent blockbusters. But oh well. In scale and scope, One is still a nighttime spectacular.

O – Oswald the Lucky Rabbit

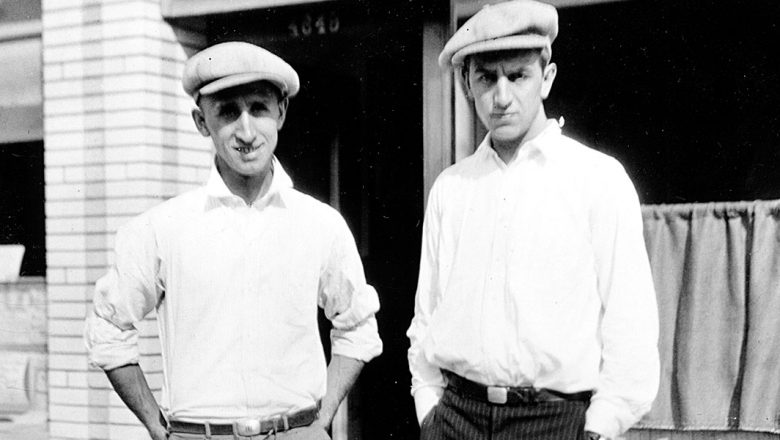

Walt and Roy Disney arrived in Los Angeles in 1926. Their journey west had been necessitated when the then-24 year old Walt’s “Laugh-O-Gram” animation studio in Kansas City, Missouri filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Walt (who “never let the truth get in the way of a good story,” mind you) remembered arriving in California with “a suitcase and a dream,” plus unfinished reels of animated “Alice in Wonderland” shorts.

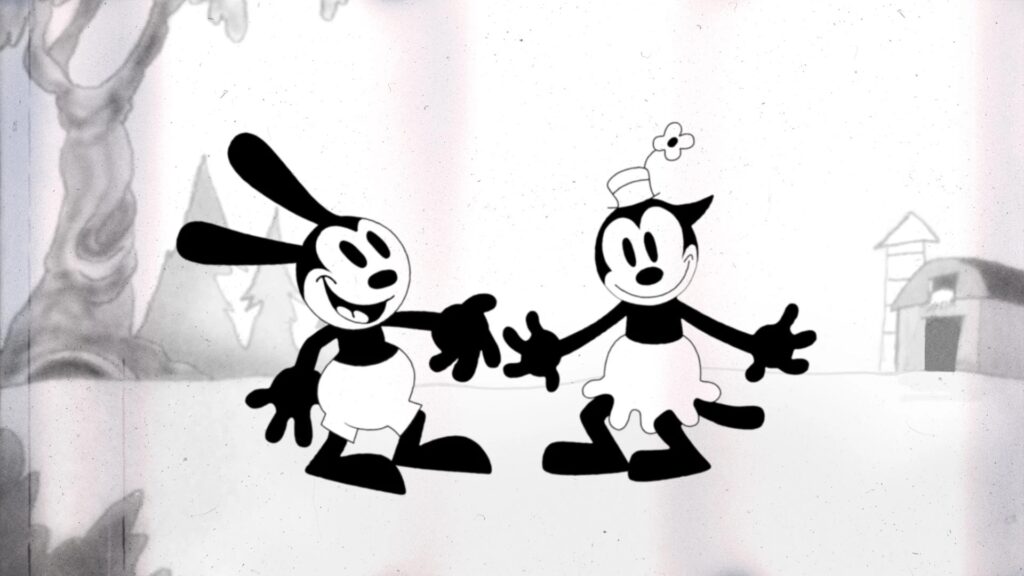

The Alice shorts did well enough that Walt could recruit a few former Laugh-O-Gram animators to follow him out west. One of them was Ub Iwerks, who would become very helpful when Hollywood heavyweight Universal Pictures contracted with the young Disney Bros. Cartoon Studio to develop a new cartoon character to star in a series of black-and-white animated shorts. Walt and Ub invented Oswald the Lucky Rabbit.

Unfortunately, when Walt tried to negotiate a higher rate for a second package of Oswald shorts, he was stunned to discover that the contract he signed with Universal Pictures gave the studio perpetual rights to the character… and Universal executive Charles Mintz had already hired Walt’s animator team out from under him. Ub Iwerks was one of the few animators to remain behind with Walt… which is lucky, because the two went on to create a new character named Mickey Mouse.

Oswald, meanwhile was left behind… at least, for a while. In 2006, then-new CEO Bob Iger made an intriguing trade. In exchange for the Oswald IP and the 27 shorts Walt had produced, Disney would give noted sports anchor Al Michaels from Disney’s ESPN to Universal’s NBC Sports. Referring to the trade, Al Michaels said, “Oswald is definitely worth more than a fourth-round draft choice. I’m going to be a trivia answer someday.”

Apart from Easter eggs and an animated short, Disney has used Oswald in two interesting ways. First, he served as the reluctant anti-hero of the video game “Epic Mickey,” which sees Mickey drawn into an alternate universe Disneyland of forgotten, cast-off cartoon characters called “Wasteland”. (In a particularly striking visual, Oswald has replaced Mickey in the park’s “Partners” statue.)

Second, when Disney California Adventure was reimagined in 2012, Oswald became the de facto star of the park’s 1920s Los Angeles-themed Buena Vista Street. While you could buy Mickey plush and “Mouse Ears” at Disneyland, the shelves of California Adventure were stocked with Oswald plush and “Rabbit Ears,” with Oswald having his own filling station near the park’s entrance! You’ve gotta admit – that’s a cool way to use this classic character, back home after 85 years.

P – Preshow

The ’80s and ’90s are often regarded as the “Ride the Movies” era at Disney Parks… It was a time when (powered by then-CEO Michael Eisner), Disneyland shook off the decades of dust that had accumulated since Walt’s death. Eisner had a bold idea: that Disney Parks shouldn’t be museums forever tuned to the pop culture of Walt’s time, and instead should be living places that featured the stories and characters to mattered to modern audiences… even if they weren’t Disney stories! In the ’80s and ’90s, Eisner green-lit dozens of substantial attractions built on a scale never seen before – what’s called the “Ride the Movies” era of theme park history.

Not coincidentally, it was also the era of the preshow… Basically, the idea that before the main show, guests would need a little bit of good old-fashioned exposition… maybe, a character who could (via video or Audio-Animatronic figure) set the stage. Even though the “Ride the Movies” era is largely over, preshows remain an essential piece of many Disney Parks attractions. For many attractions, they are “unskippable” narratively – in other words, you wouldn’t exactly understand what’s going on if the preshow flickered out of existence.

The pre-show is an invaluable tool for designers, used to introduce characters, set a tone, give guests their role, and establish the story – including any mission or goals – while maybe sneakily including required safety spiels without breaking the story. Some preshows are as beloved as the rides that follow (like Soarin’); some preshows are expertly blended into the queue (like Indiana Jones Adventure); and some are practically or even literally attractions in their own right (see, “U”).

Q – Queue

It’s unfortunate that P comes before Q in the dictionary, because this entry and the prior are swapped from their real-life order. A queue is, of course, a line. But how we got there is fascinating. In fact, we dove into the history of lines at Disney Parks in a standalone in-depth feature. Suffice it to say that lines have gone through a lot of evolution in the last seventy five years. (See also, “V”.)

It’s fascinating to think that when Disneyland opened in 1955, the queues for most of its attractions were painfully simple: chains strung up between poles, creating back-and-forth corrals for waiting guests. It was actually Walt’s visit to Knott’s Berry Farm in nearby Buena Park in the ’60s that changed his perspective. Instead of leaving waiting guests in a corral, Knott’s new ride instead hid the queue in a desert landscape wrapped in rockwork. Walt reportedly said to the ride’s designer, Bud Hurlbut, “Bud, you ole son of a bitch!” He loved the idea that a themed queue would integrate guests in the environment before they’d even stepped aboard the ride – and more to the point, that it could hide the crowd so guests would be more likely to hand over a ride coupon (see, “E”)

As a result, you’ll see that rides from the late ’60s and ’70s do exactly that – wrapping queues into environments or setting the stage. Then, in the ’80s and ’90s – what’s sometimes called the “Ride the Movies” era – it got wilder. By then, the queue genuinely became part of the attraction, delivering key information. When you ride Star Tours or Indiana Jones Adventure, the queue is inseparable from the larger experience – it’s part of the story! That trend continues unto today. For example, our oft-cited “next generation” ride – Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance (see, “U”) is often noted as the first attraction that truly blurs the line between “queue” and “ride.”