Like most Millennial theme park enthusiasts worth their salt, I cut my teeth for park operations in the industry in that most common of test beds: Roller Coaster Tycoon on a Windows 95 desktop computer while Windows Media Player repeated Michelle Branch’s The Spirit Room in the background.

If you were unlucky enough to miss this essential era of theme park fandom, Roller Coaster Tycoon presented you with a number of “scenarios” you could choose from – Forest Frontiers (a wooded landscape with a small on-property pond); Evergreen Gardens (a compact property that asked you to build-out a sort of fine British botanical gardens); Millennium Mines (a tricky one, requiring you to make use of a sort of depressed quarry of rock).

The scenario you chose was fundamental. After all, each came with only a few kinds of rides already available, costs to “research” new rides, and strict budget to build with. And though you could add trees or remove them; terraform to carve out canyons or fill waterways; build bridges or tunnels, every click of the mouse wheel resulted in a red, negative dollar amount rising from your action. A player could (and in my case, often did) go bankrupt in service of trying to create something astounding if you failed to balance the realities of attendance; the costs to the consumer; and the tastes of a computerized audience. For many of us who’ve now graduated into armchair Imagineering, Roller Coaster Tycoon taught us the most frustrating and basic rule of making a theme park: ultimately, you have to be realistic…

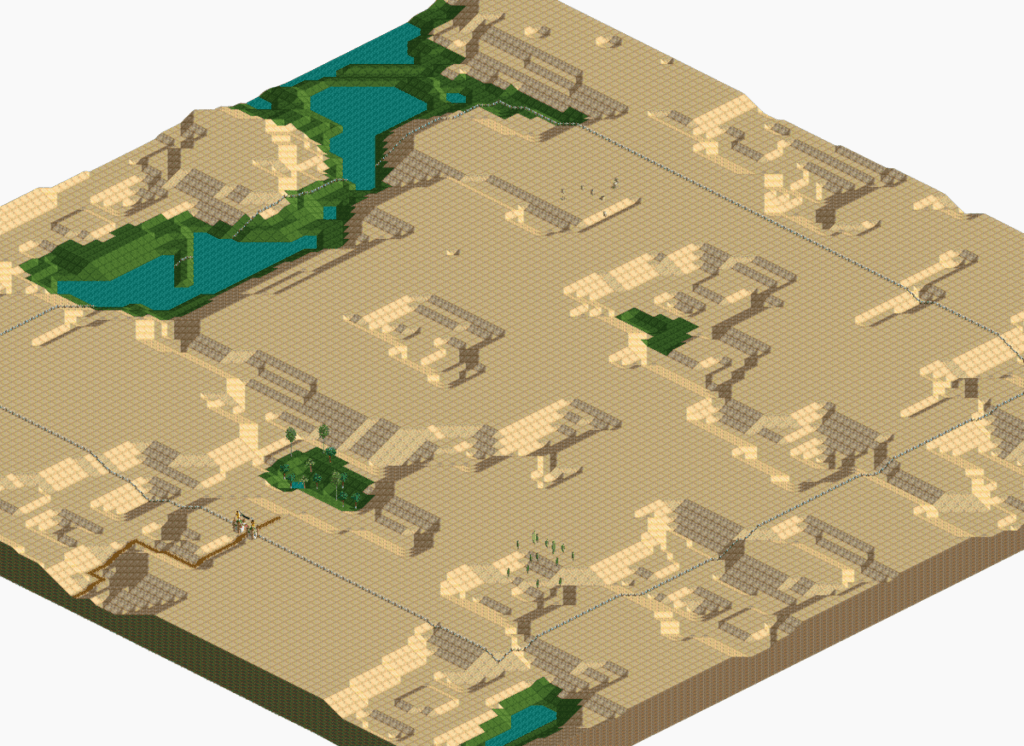

… Unless you were smart like me. Then you knew that there was really only one level of Roller Coaster Tycoon you ever really needed to play. Arid Heights. If you were unfortunate enough to have missed the “Loopy Landscapes” expansion pack, you might not know the glory of Arid Heights.

Boring as it might’ve appeared upon first load, Arid Heights was a game-changer. Here, in the most simple and boring of beige, featureless landscapes, was true, concealed beauty. Because Arid Heights had three career-affirming features:

- It was a vast, expansive, limitless desert with few discernible landmarks and practically no obstacles to development;

- It came with dozens of rides available, with no need to focus on time- and budget-consuming “research” to unlock them; and to that end;

- In Arid Heights, money didn’t exist. There was no budget. No cost to place a tree, level a pit, or build a roller coaster

For a young wannabe theme park designer like me, it was heaven on Earth; a (no pun-intended) sandbox wherein whatever I wanted to try – no matter the cost – I could. It was a beige desert, sure, but I had a blank check to make it whatever I wanted. Give me time and Arid Heights could become a waterside boardwalk; a botanical garden; a mountainside resort; a beautifully forested park, with only the damned unalterable squares beyond its perimeter fence ever betraying that it was once a desert, too.

Arid Heights removed the pesky irritation of planning, budgeting, or thinking strategically. In that desert, I could do whatever I wanted.

There was just one minor irritation: since money didn’t exist in the world of Arid Heights, admission to the park was – by default and unchangeably – free. A fair trade, I guess. But can you imagine if despite me not having to pay to design and build the park, those little computerized guests still had to pay get in? That’d be paradise… at least, for me.

And here we are – May 8, 2025 – and I’m starting to think maybe those nice folks at Hasbro a quarter century ago might’ve based Arid Heights on a true story.

Parks & People

When it comes to theme parks, there’s a sort of “natural order” to things. Logically, theme parks emerge where people either reside or vacation.

Actually, it’s sort of always been that way. After all, the “origin story” of the industry is often told in bifurcating halves – of the urban “trolley parks” that emerged in the late 19th century (often spurred by intracity trolley lines eager to increase weekend ridership, ushering industrial-era city-dwellers out to gardens, carousels, and Sunlite pools), and of the sort of seaside pleasure piers and boardwalks marked by dance halls, thrills, and the marvelous wonders of the electric lightbulbs.

Many of these “early” amusement parks still exist – from New York’s Coney Island to Ohio’s Cedar Point; the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk to Pittsburgh’s Kennywood. From trolleys to personal automobiles; the wonders of domestic flight to international aviation. The story of amusement parks has always been the story of where people are. At least in regards to the United States, it’s often said that America is saturated; that every metropolitan area that can support an amusement park has one – hence why the last half-century has been more about those parks changing hands and consolidating under corporate leadership than about new parks opening.

Instead, focus for those operators has turned international. And if you’re following the story of people, you can see why. The United States touts a population of 330 million who, in a sense, “share” six Disney Parks, four Universal parks, and the dozens of Six Flags, Cedar Fair, Herschend, and family parks that litter the country.

So is it really any surprise that the second Disney CEO Bob Iger saw a cautiously-permissive crack in the media firewall that’s surrounded China and its 1.4 billion citizens in the 2000s, he took a swing that resulted in Shanghai Disneyland? Is it a surprise that Iger expected the project to be his career capstone? Disney went where the people were (and yes, perhaps was willing to push some ethical compromises into the peripheral).

And Shanghai Disneyland didn’t just meet the people where they are; it met them at the right time – just as China develops the same kind of post-industrial emerging “middle class” with leisure time and expendable income that America created in the ’50s! (And thus, the same conditions that created the original California Disneyland.)

So is it a surprise that Universal followed suit with park in Beijing? Indeed, for decades, fans have supposed that eventually we’d see a “destination” brand set down a park in India – another country boasting a 1.4 billion population, or four times that of the U.S. But for the anomalous creation of Universal Epic Universe, it would be fair to suppose that neither Disney nor Universal would ever break ground on a new theme park in the United States again! Saturated and satisfied, the people here have enough, and the people elsewhere represent nothing but potential.

Yes, the story of amusement parks is the story of people. Until it isn’t.

The Middle East Movement

For more than a century, people have beget amusement parks. But for the better part of two decades, the Middle Eastern nation of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has wondered aloud if the formula can be reversed.

This desert nation – wedged between Oman and Saudi Arabia on the Persian Gulf – is home to just 9 million residents; the population size of, say, Estonia or New Zealand. More to the point, that’s quite literally the population of New York City, and about a third the population of the city of Shanghai alone. But the UAE has a trick up its sleeve by way of the two heavily-interrelated things that are widely known about it:

- that it’s home to the two innovative hot market cities of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, and

- that it’s absolutely flush with immense, unimaginable riches thanks to the UAE’s home-grown cash crop: natural gas, oil, and petroleum

After the discovery of oil in the 1960s, the UAE has been on a fairly continuous streak of unnatural and almost caricature-ized growth, resulting in a nation that flaunts its wealth in ways that would leave the Tower of Babel quaking. Despite temperatures regularly residing above 105°, the UAE would position Dubai as a city of luxury, innovation, architecture, and glamor – an ever-expanding metropolis that (by appearances) borders on a science-fiction utopia reigned over by the world’s tallest building (the Burj Khalifa), itself surrounded in artificial waterways that snake through the city, throwing water 500 feet into the scalding air of the Arabian Desert.

Since the early 2000s, Arabian Peninsula countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE have launched an all-out media blitz to reposition their countries (often viewed as religious-conservative nations embroiled in perpetual conflict) as places worthy of tourism dollars. Through bottomless funding, they’ve cultivated a carefully-curated vision board that positions their industries as innovative; their cultures, progressive; their cities, destinations!

The very fact that you’ve likely heard of Dubai and Abu Dhabi – and that they might conjure visions of art deco buildings, fountain shows in crystal lagoons, man-made islands, water slides, and yes, theme parks – shows that the UAE’s marketing plan is working. These two cities – about an hour’s drive from one another – are the the midst of an astroturf reimagining meant to elevate them as “global cities” on par with New York, London, Paris, Tokyo, Los Angeles, Shanghai, Cape Town, and Hong Kong.

Of course, we can go no farther without saying out loud that Human Rights Watch notes that “the UAE has promoted a public image of tolerance and openness […] while restricting scrutiny of its rampant systemic human rights violations” including:

- “severe restrictions on the rights to free expression, association, and assembly”;

- holding “disproportionate control over migrant workers under the kafala sponsorship system that prevents them from changing jobs without their employer’s consent” – a condition that the country’s critics call a form a slavery underwriting the nation’s rapid expanse by way of forced labor construction projects;

- establishing a legal definition of domestic violence that “reaffirms male guardians’ legal right to discipline their wives, female relatives, and children” and “does not criminalize marital rape”;

- criminalizing all “consensual non-marital sex” and all abortions;

- criminalizing “vaguely-defined LGBTQ+ acts, allowing the authorities to arrest people for a wide range of behaviors including public displays of affection, gender nonconforming expression, and campaigns promoting the rights of LGBTQ+ people”

Obviously that’s to say nothing of the nation’s pivotal role in the climate crisis. But none of that managed to cool the country’s hot pursuit of expanding its tourism aspirations in the 2000s, when several high-profile projects from American entertainment companies were announced… Read on…