Disney’s FASTPASS

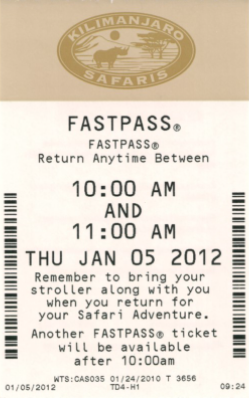

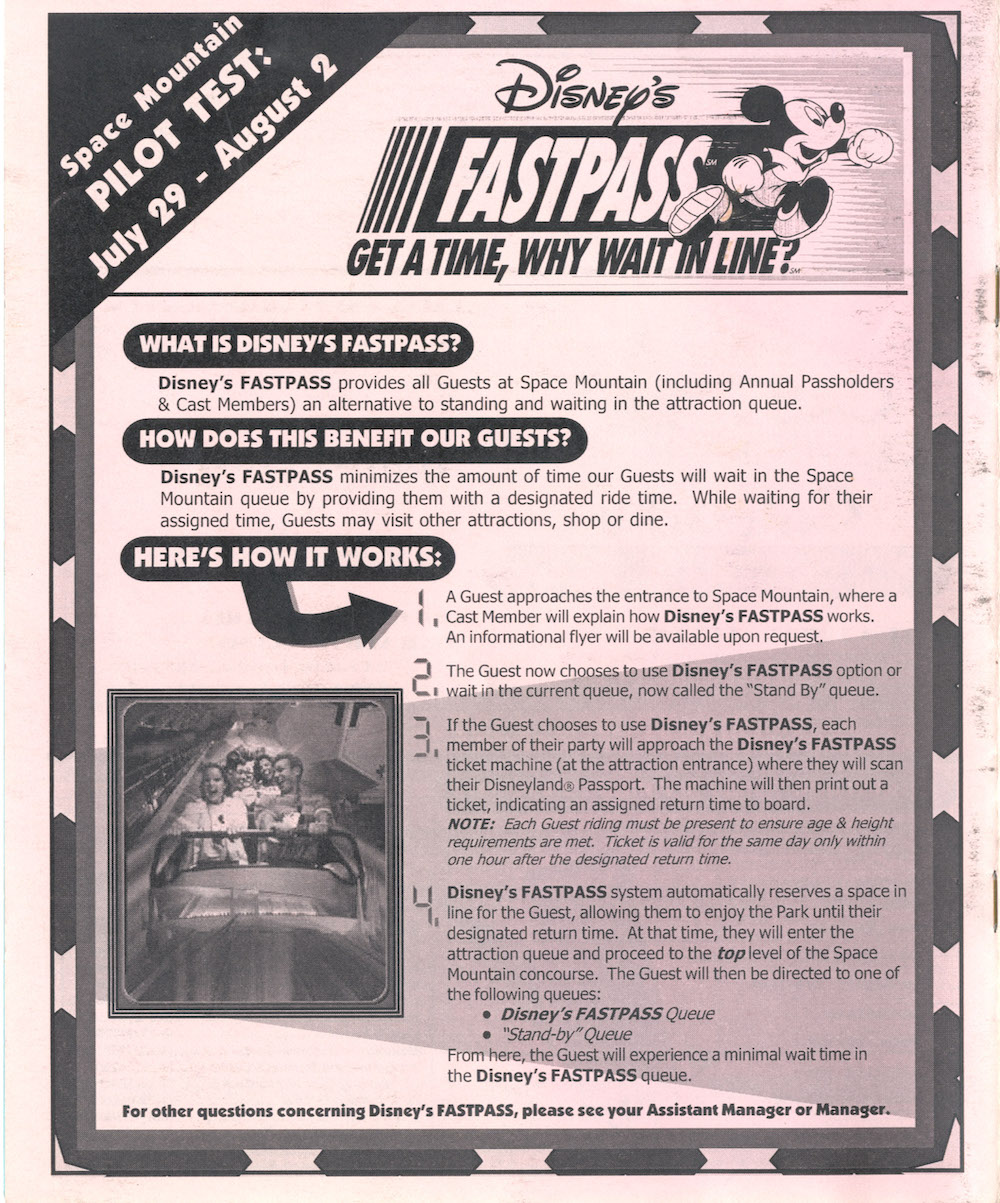

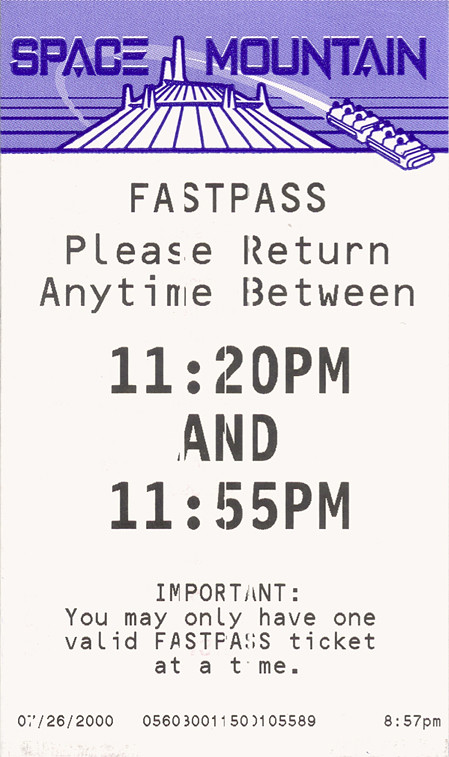

Disney’s FastPass was initially launched in its official form – the familiar ticket-scanning kiosks, paper return tickets, and hour-long return windows – in 1999. At first, it was installed at just six attractions in all of Walt Disney World: Space Mountain, Splash Mountain, Kilimanjaro Safaris, Kali River Rapids, the Lost Legend: Countdown to Extinction, and the first ride opened with FastPass “built-in,” Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster. At Disneyland, it was tested with Space Mountain, then added to “it’s a small world holiday” and Indiana Jones Adventure.

You can imagine that, in the early rollout of this system in 1999, the prospect of a “Virtual Queue” didn’t exist, and FastPass was not in the popular lexicon. To that end, many guests reported dissatisfaction with seeing others “line-jump” to gain priority access via a Disney-sanctioned process. A few physical fights are even said to have broken out in response to the percieved “line-cutting.” (“Unfair waits are longer than equitable waits,” Maister says.)

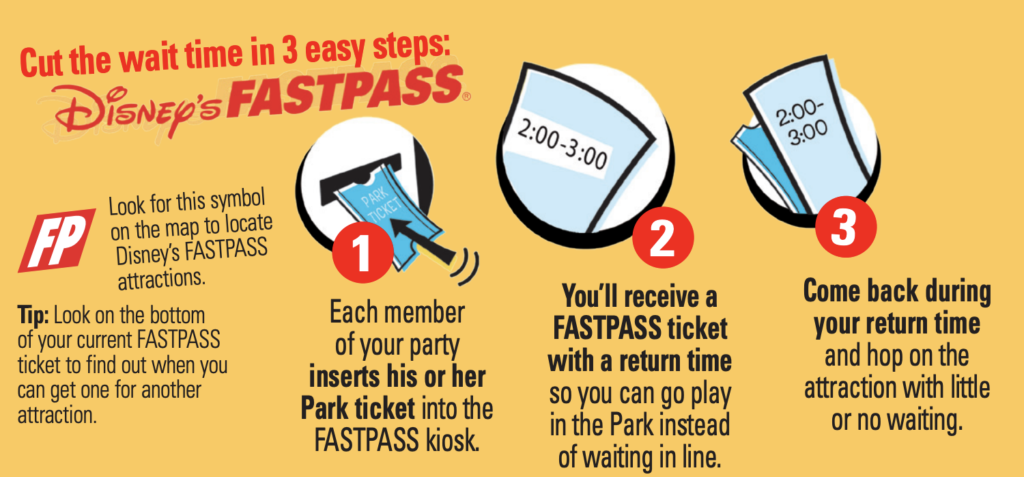

Making guests aware of the service was half the battle. Even then, some guests reported that the “return time” windows impeded on their plans and interfered with the day’s spontaneity and flow. (If only they knew what was to come…!)

But in general, each park offering one, two, or three FastPass-enabled attractions (typically, its select highest-popularity-medium-capacity rides) was the kind of revolutionary idea that could’ve redefined Disney’s association with waits – exactly what engineers had hoped…

Of course, as we know, FastPass is long gone. Before we go any further into the story of FastPass and Disney’s virtual queues, it’s important to recognize how FastPass worked… and how it didn’t.

How FastPass worked

What Disney’s FastPass did is to take a ride’s operational hourly capacity and do some simple math to redistribute it. If Space Mountain could realistically accommodate 1,800 riders each hour, then it essentially has 1,800 slots to fill with riders between 10:00 and 11:00; another 1,800 from 11:00 – 12:00, another from 12:00 – 1:00, through the day.

The FastPass system set aside a percentage of those “slots” (for many rides, reportedly up to 70%) to be booked into by guests (initially, day-of, on a rolling basis through the day until that set-aside capacity was all claimed). In theory, the new “FastPass” queue became the primary means of boarding an attraction.

The old “regular” line became the “Stand-by” line – as its name implies, an option for guests who were uninterested in or ineligible for a FastPass (for example, because the ride’s FastPass capacity was already fully claimed for the day, or due to already having one outstanding at the time) and were willing to accept secondary boarding preference. Like hoping an empty seat becomes available on a flight, a guest waiting “Stand-by” would be at the mercy of chance – or, of a Cast Member at the “merge” point, directed to admit only so many “Stand-by” guests to a much larger ratio of “FastPass” guests.

To return to our Space Mountain example, a guests arriving at the ride at 9:30 AM might be given the choice between a 25 minute “Stand-by” wait, or securing a FastPass with a 10:10 to 11:30 return window – a two-hour wait in a virtual queue, followed by a shorter wait in the physical FastPass line.

Guests opting for the latter might spend the the two hours snacking, shopping, seeing shows, queuing for lower-capacity rides, riding high-capacity FastPass-free attractions like Haunted Mansion or Pirates of the Caribbean, or waiting in the “Stand-by” line of another of the park’s E-Tickets before returning to Space Mountain between 11:30 and 12:30, entering through a FastPass queue, and swiftly boarding the ride with just a few minutes’ wait.

Especially for guests who knew how to leverage the FastPass system to effortlessly sail past “Stand-by” lines, it could be easy to imagine that FastPass was a panacea for Disney Parks’ problems. FastPass, it seemed, allowed everyone to do and see more! Except…

How FastPass did not work

A ride’s capacity is its capacity, period. And this is important, because it’s the crux of what would become the major fault of the system: FastPass couldn’t actually make a ride process more guests in any minute, hour, or day. It would merely redistribute how a ride’s existing “slots” were allocated, setting a majority of them aside for pre-booking – and thus, for guests willing (and able) to navigate the system’s bylaws and logistics.

In other words, with or without FastPass, Space Mountain’s theoretical hourly capacity is 1,800 people per hour. The only difference is that with FastPass enabled, 1,260 of those “slots” every hour would be already spoken for by guests out in the rest of the park.

That had two pretty staggeringly negative repurcussions.

First, it meant that for every attraction newly equipped with the “perk” of the FastPass service, an associated “Stand-by” line was created. Though you might enter Space Mountain’s “Stand-by” line as the 541st person, the wait time would display as an hour. That makes sense since you’d actually be 1,801st in line – behind 540 guests physically in front of you and 1,260 waiting in FastPass’s virtual queue.

But the result is that across the park, high capacity rides able to effortlessly process guests were bogged down with swampy, slow-moving, stagnant “Stand-by” lines, filled with fewer people, but moving only 30% as quickly as they had before. And by nature of FastPass’s widespread use, it meant that invariably, most of your waits would be “Stand-by.” Most guests, then, would actually wait longer over the course of a day due to FastPass, merely offset by the feel-good sensation of those handful of line-jumps… if you knew to use FastPass at all.

The second negative effect of FastPass is one that was far less subtle. In September 1999, the Orlando Sentinel ran a story reflecting on the first few months of FastPass, by chance capturing two quotes that are of monumental importance to our story:

[Guest] Stan Bonny, 61: “I think it’s a great idea. It should be on all the rides.”

[Vice President of Operations, Planning and Development at Walt Disney World] Dale Stafford: “If you did it everywhere, you wouldn’t have enough space in the park. Where would everyone go?”

Frankly, this is where our full look into FastPass segues into a controversial Passholder-exclusive Editorial here on Park Lore: our hard-nosed look at why technically, Disney Parks Would Be Better Without Any Virtual Queues. In it, we dissect the eight quantifiable ways FastPass probably hurt your vacation more than it helped, including the answer to that question. Where does everyone go when every major attraction (instead of just one or two select ones) offers FastPass? You already know the answer:

- They clog pathways, pulled through currents of people ambling around looking for something to do while waiting for their return time or their next available FastPass instead of being held in E-Ticket queues acting as “sponges” like they’re meant to;

- They descend en masse on smaller, non-FastPass-enabled attractions whose queues and capacity can’t support the gargantuan groups looking for something to do; or

- They decide to join the Stand-by queue for attractions they don’t have a FastPass for (which, as we’ve already acknowledged, mires them in slow-moving, stagnant lines for most of their rides for the day, far outweighing the time saved by a handful or less of FastPass rides).

That last one is particularly important, because the first obvious evidence FastPass’s failings began in the 2010s. That’s when Disney announced an unprecedented project of a scale never quite seen before that would truly reinvent a Walt Disney World vacation…

What really bothered me during my sole post-fastpass trip relates to this idea that “Unfair waits are longer than equitable waits.“

If a ride goes down due to weather or maintenance, when it comes back up they prioritize the Lighting Lane and drastically increase the ratio of Lightning Lane to stand-by guests.

During my trip I had not purchased Genie+, so it was horrible waiting in the excruciatingly slow stand-by after a ride name back up. When FastPass was complimentary to everyone, this same scenario didn’t bother me, as I would also benefit from the operational change when my FastPass return time came, however, in this new system, these ‘higher-tiered’ guests were prioritized making the wait feel particularly inequitable and ergo felt way longer.

My biggest takeaway from this is how short Expedition Everest’s line was in 2015. Less than 30 minutes? Sign me up! I am glad others agree about the issues with Fastpass and I now have a place to link them to on why.

I think your solution is an interesting one. I agree that fastpasses should be cut down to larger attractions but I have never heard the idea of not opening it until the standby hits a certain time quota.

I think we could see some interesting queue changes in the future here!