“Explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better, but the frog dies in the process.” – E.B. White

If you ask Imagineers or executives, story is what’s at the heart of Disney today, best embodied by its theme parks. And it’s true that the scale and scope of Imagineering in the 21st century – largely bolstered by story – had grown beyond imagination, yielding an era of “Living Lands” supported by massive mythologies and built-out worlds. Story directs the food, characters, and even souvenirs of Hogsmeade, Batuu, Pandora, and beyond…

Yet for all the deeply-rooted environmental-and-atmospheric stories unfolding in the “Living Lands” admired today, story is also the foundation of – and possibly, the fault in – a project often ranked among “the worst Disney Parks land ever“: Chester & Hester’s Dino-Rama. Today, we’ll dig deep into this cringe-worthy carnival to prove once and for all that there’s more than meets the eye to this primeval parking lot fair…

Trust us, by the end of our dig into and defense of Dino-Rama, you’ll at least know that this carnotaur carnival does have a reason for being, and a story as rooted as that of Pandora. But then again, if it takes a (brace yourself) 5,000 word Park Lore feature to make this joke make sense, maybe it’s not a joke worth telling… So bring your hammer, chisel, and brush as we set out toward the (almost inevitable) extinction of Dino-Rama…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

The Disney difference

There has always been something that made Disney’s theme parks different.

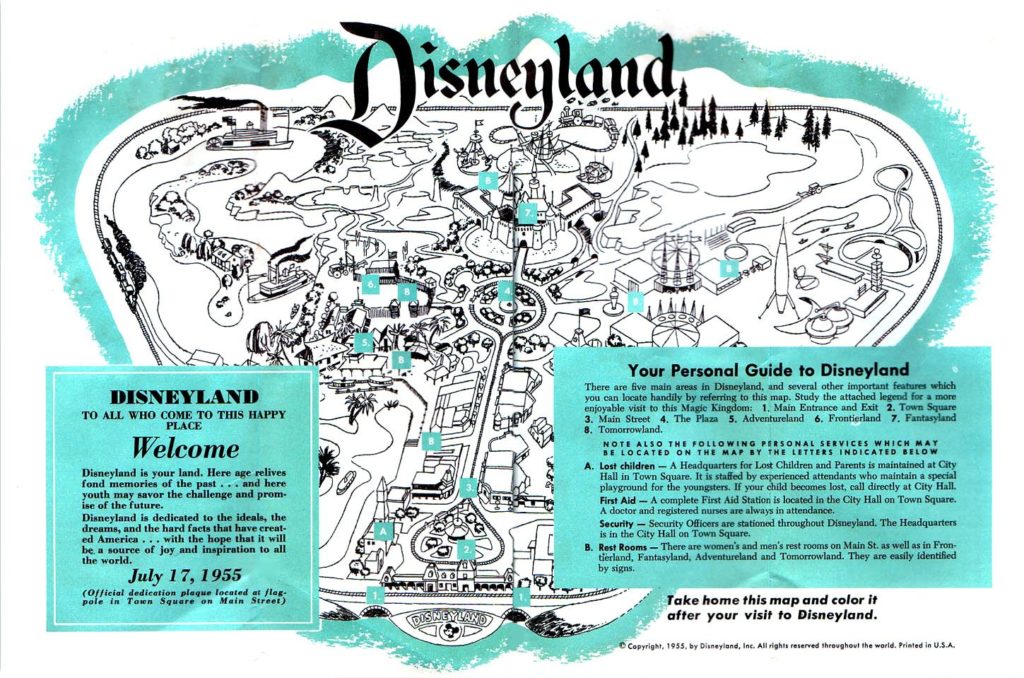

In part, fans often cite Disneyland’s original innovations – its gated entry, nostalgic “Main Street,” hub-and-spokes layout, themed lands – and that’s all true. Likewise, it’s often said that Disneyland differed so greatly from parks of its era for having been built by a cohesive team of filmmakers rather than competing “carnies” that defined amusement parks and boardwalks, and that’s true, too.

But frankly, each of those has been co-opted by post-1955 theme parks built, licensed, or bought by Universal, Paramount, Warner Bros., DreamWorks, SeaWorld, even Cedar Fair and Six Flags, and yet still Disney’s theme parks remain different. So what’s the secret ingredient?

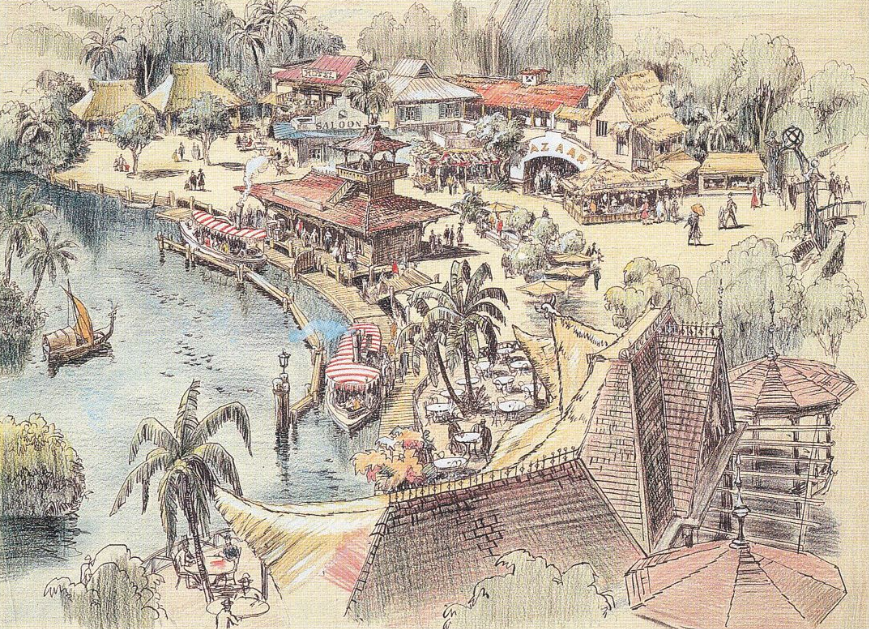

You might call it romanticism. Inherent in the early DNA of Disneyland’s themed areas, designers didn’t bother recreating the real world; they brought to life a version of the world that’s better than reality; an Adventureland born of the era’s collective vision of “adventure,” and thus more adventurous than any real jungle port. Frontierland doesn’t look like any actual frontier settlement; it can’t be pinpointed on a map; yet it’s a perfect embodiment of the Old West as it will forever exist in pop culture.

But that romanticism is never more apparent than on Main Street. Perhaps because it’s often said to have been born from Walt’s own childhood memories of small town, U.S.A., Main Street is a masterwork in romanticism. No one would mistake it for real, yet it feels right; grand, glowing, and glorified, with all its social inequalities blurred away, passed through a lens of fantasy. This isn’t our actual past, but it’s the image of the past we as a society share. It’s our fantastical foundation; who we tell ourselves we are.

That secret ingredient was brought east, inherent in the Americana of Magic Kingdom; exported as-is to Tokyo Disneyland; translated to corporate and cultural messaging in EPCOT; described in (the most enduring) parts of the Disney-MGM Studios as “the Hollywood that never was, but always will be”; refracted through further fantasy prisms in Disneyland Paris; and absent from Disney California Adventure until its billion dollar addition. But then, there’s Disney’s Animal Kingdom.

First, we have to acknowledge that “Disney’s Wild Animal Kingdom” was envisioned with a theme. Not decorations, mind you, but a philosophy; a mantra; a theme underlying every decision designers made, filtering to every inch of the park’s design and its attractions. To hear lead designer, iconic Imagineer, and authentic adventurer, artist, traveler, and anthropologist Joe Rohde tell it, the centering messages of Disney’s Wild Animal Kingdom were set: the intrinsic value of nature (that is, nature is enough regardless of its “usefulness” to Man); transformation through adventure; and a personal call to action. These underlying themes would permeate through the park – a subtle but substantial message… but they’d also ensure that this Disney theme park looked and felt unlike any to come before.

In one of Park Lore’s Passholder-exclusive Special Features, we explored the design and development of Animal Kingdom through Joe Rohde’s eyes and words – a must-read for armchair Imagineers. But one of the most compelling perspectives Rohde brought to the park is a major revision to Disney Parks’ normal romanticism.

Sure, like Adventureland and Frontierland, none of Animal Kingdom’s themed areas could be specifically pinpointed on a map; they’re stylized amalgamations of real places and times, layered with immense realism by way of true artisans and historians. But more to the point, in a park exploring the intrisic value of nature, transformation through adventure, and ending with a personal call to action, these depictions of global locales could not be romanticized; they would need rooted in reality and accuracy!

The park’s Africa is a perfect example. Brought to life by way of the village of Harambe, Rohde noted that the land is rife with evidence of the supremacy of nature; organic forms dwarf man-made ones; evidence of improvization abounds; people in this pseudo-documentary village clearly revere and inhabit a natural world. Put simply: Animal Kingdom’s lands are fictional, but they are not a fantasy.

Africa’s village of Harambe is a commercial bazaar; a town that’s carefully measured the value equasion of conservation and decided to place its bets on the intrinsic value of nature. As ever, it’s not a real place, but nonetheless offers an opportunity to be transformed through adventure and a personal call to action.

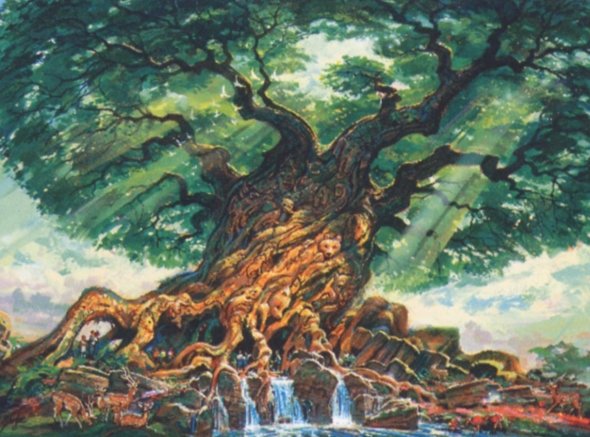

So it would be the park’s Asia, incarnate as Anadapur, a riverside kingdom whose misty ruins and historic Maharajah hunting grounds now served as a wildlife sanctuary, including a river ride through animal habitats. Discovery Island stood as an artisan village; a hub of the celebration of nature, built into the winding root systems of the towering, central Tree of Life. Even though the land wasnt an fairy tale, it was still a story, inviting guests into a world modeled off the real thing, but with a spirit and style all its own.

And so it would go for two more lands, which would take guests to places no zoo would dare go…

Ancient animals… almost

As we know from Michael Eisner’s opening day dedication, Disney’s Animal Kingdom was eventually organized by a guiding principle that it celebrate animals “real, ancient, and imagined.” Those latter two, it was thought, would be Disney’s coup; the draws that would ensure Disney’s Animal Kingdom was “Nahtazū” (or at least, not just a zoo) in the eyes of the public… and therefore, worthy of Disney admission prices.

It’s well-known among fans that in the park’s early drafts, Africa, Asia, and Discovery Island would be joined by two others lands: the grounded Dinoland and the ethereal Beastly Kingdom. While plenty has been said about the latter (including our in-depth and much-cited Possibilityland: Beastly Kingdom feature), fans sometimes forget that that Dinoland was just as conceptually unique.

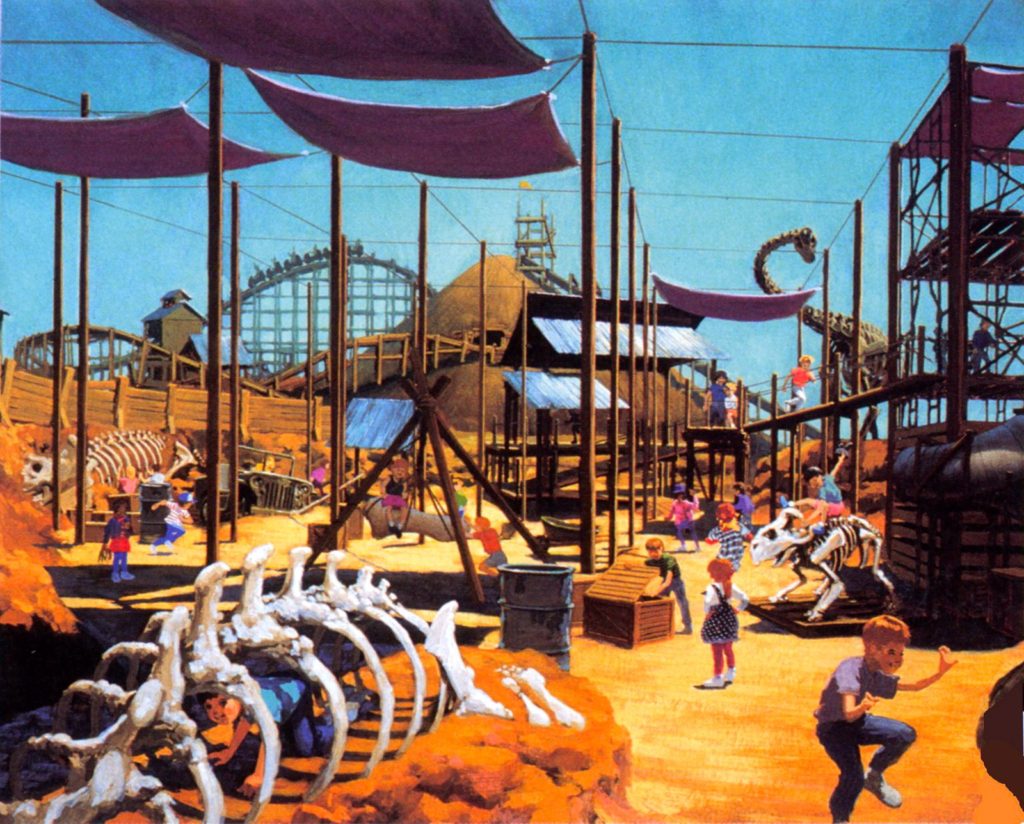

Even then, early artwork and stories from industry writer Jim Hill make it clear that Dinoland would be set somewhere in the United States; a once-sleepy desert town unexpectedly enlivened by the discovery of fossils, initiating a decades-long transformation into a… well… a tourist trap. In a clever set-up, that initial dino-discovery (plus a few decades of time) would’ve segmented the land in two, each featuring a significant ride.

First, the fossil find would’ve drawn academics from around the country who slowly established the Dino Institute. Eventually, this field research group would construct the Dino Institute and – in the 1970s – its research museum.

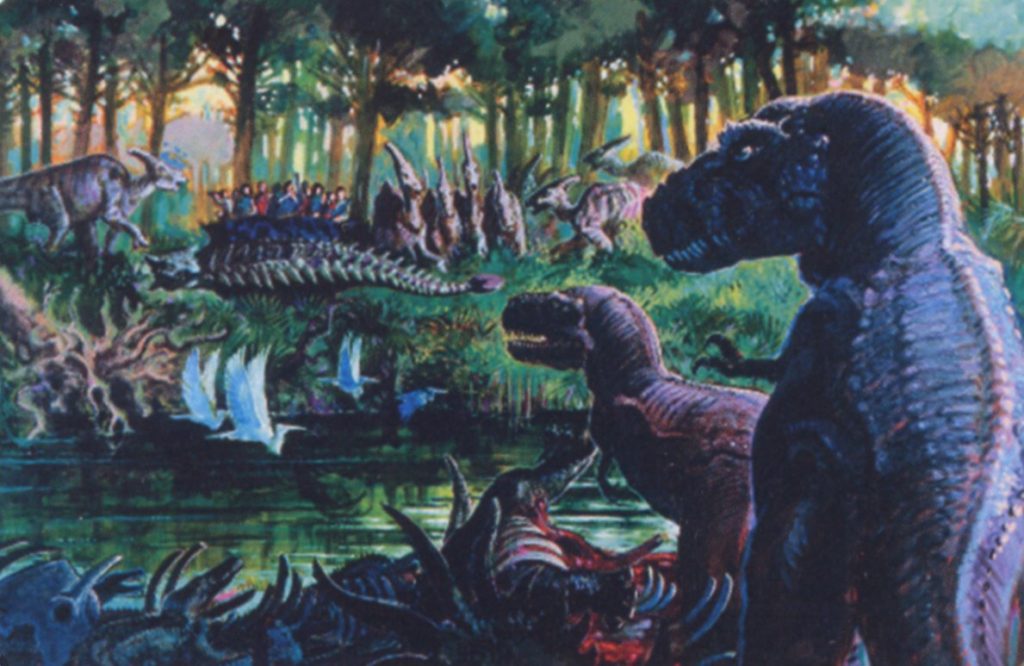

Given that Imagineers originally intended each of the park’s lands to have its own “Kilimanjaro Safaris” equivalent, the Dino Institute would house Dinoland’s: a “time traveling” family attraction wherein guests would board Ankylosaurus shaped vehicles and travel to a prehistoric jungle (partly outdoors, behind the Institute showbuilding) to tour past Audio-Animatronic dinosaurs in their “natural” habitats.

The second half of the land would belong to the locals who, spurred by the influx of grad students, would’ve proudly restaged sleepy Diggs County as a roadside attraction of dinosaur “wonders,” like their reclamation of old, uncovered dig pits as must-see attractions.

Of course, this part of the land would also contain the towering Excavator – a steel roller coaster (cleverly disguised as wooden… think California Sceamin’) rumbling through the town and passing “artisan”-made dinosaur sculptures (reclaimed rusted metal builds) amid the long-since-emptied dig pits of the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s.

Obviously, neither the Excavator nor the family safari came to be. Why? When guests stepped into Dinoland at Disney’s Animal Kingdom in 1999, the land resembled its original incarnation, but with at least a few notable changes… Read on…