Shattering glass. Pitch black darkness. Pulsing heartbeats. Sparks illuminate a twisted, spider-like figure with gnashing fangs and horrible claws, its eyes fixed on you… Wings beat against the stagnant dusty air, thick with breathless horror. A guttural growl rumbles inches from your ear. Warm, thick drool drips against your neck… This is the end.

Though it may sound like the horrific makings of a paralyzing nightmare, a carnivorous insectoid alien was set loose among the crowds of Magic Kingdom every ten minutes or so, every day, for eight years. With one of the shortest lifespans of any attraction to occupy a Disney Park, The ExtraTERRORestrial Alien Encounter (emphasis included) has developed a cult following from those who experienced — and in some cases were traumatized by — Disney’s edgiest attraction.

In the hazy view of hindsight, Alien Encounter has become little more than a memory for some, and an urban legend for many, many more. But that’s what we’re here for: to capture the full stories of closed classics and forgotten favorites for a new generation, while allowing Imagineering fans to relive the rides of yesteryear. Today, we’ll walk you through the making of this one-of-a-kind Disney attraction, endure the harrowing experience of Alien Encounter from the entrance doors to the exit and then discuss what brought about its demise. Think you know the story of Disney’s scariest attraction ever?

Naturally, the story of any Imagineering experience begins long before the first guests ever step inside… And today’s tale begins with a prologue familiar to fans of Disney parks history… Strap in…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

The Disney Dark Ages

During the 1970s, Disney was in decline. Though it’s difficult to imagine today, the decade after Walt’s 1966 death had seen Walt Disney Productions spiral into obscurity, with the studios’ films faltering at the box office. Movies like The Black Hole, The Watcher in the Woods, Dragonslayer, Something Wicked This Way Comes, and The Black Cauldron simply failed to land, and one after another, Disney’s descent looked less and less likely to ever reverse. Could it be that “Disney” was simply a tarnished studio that wasn’t meant to outlive its iconic namesake?

By the end of then-CEO Ron Miller’s tenure in the early ’80s, it appeared that Disney was destined to fall to corporate takeovers that would undoubtedly sell of the company’s assets and licenses for good. Luckily, Walt’s nephew, Roy E. Disney (who retained a seat on the board of directors) decided to fight back. His first “Save Disney” campaign ended in the ousting of Miller, to be replaced by someone Roy had helped hand-select…

In 1984, Frank Wells (left) and Michael Eisner (right) became the president and chairman of Walt Disney Productions. With extensive résumés at Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures, respectively, the duo were chosen very intentionally by Disney board member (and leader of the “Save Disney” campaign) Roy E. Disney with hopes that their cinematic experience could revive the company’s core business — its live action and animated studios.

As we know, they succeeded wildly, kicking off the so-called “Disney Renaissance” with 1989’s The Little Mermaid, with a string of critically-acclaimed box office blockbusters that lasted a decade. But all the while, Wells and Eisner also expanded Disney as never before. In fact, Eisner’s acquisitions of ABC and ESPN literally helped rename Walt Disney Productions to today’s Walt Disney Company, forming the basis of the international media conglomerate we know.

But Eisner’s massive transformation of Disney also included taking a fresh look at its theme parks, which had similarly stagnated in the ’70s (mostly marked by bare steel coasters rather than the epic dark rides of the ’60s overseen by Walt, like Pirates and Haunted Mansion). Though he admitted to knowing significantly less about theme parks than films, he was determined to get hands-on to give them a new lease on life, too… and it would change the parks forever…

Pop Parks

As part of Eisner’s onboarding with Disney, he was invited to tour Disneyland with his family. As the story goes, the new chairman asked his pre-teen son Breck to come along, only to have him retort, “Dad, that place is for babies.” Naturally, that insinuation horrified Eisner. For all the work he was planning that would modernize Disney’s studios and make the brand relevant again, his own son was reporting that Disney’s theme parks were old-fashioned, tired places that teens detested. And frankly, he was right.

Think about it — Disneyland and Walt Disney World were still largely products of Walt’s time thirty years earlier. They boasted dusty Frontierlands echoing the heyday of The Lone Ranger and Davy Crockett (with the “Old West” long since left behind in popular media), aged Adventurelands promising the mid-century exoticism of Africa leftover from the ’50s, and tired Tomorrowlands of the long-gone, pearly white, naive Space Age.

Eisner made a pledge then and there to change the perception of Disney’s theme parks, bringing Breck along for a tour of WED Enterprises (today, Imagineering). It’s there that Eisner green-lit projects left and right, with particular emphasis on thrills, media, and pop culture. And what could be wrong with that? Just as Walt himself had shaped Disneyland to the tastes of the 1950s, Eisner decreed that the parks should evolve to cater to today’s pop culture.

For example, in a record 100-day turnaround from concept to opening, on June 22, 1985 Disneyland debuted Videopolis — a live entertainment venue that would transform each evening into a teen-oriented dance club, broadcasting top 40 music videos on 70 massive video monitors. The makeshift “nightclub” was designed to give Disneyland an edge in attracting young people and refreshing its identity. It worked.

Still, it was merely the first step in Eisner’s quest to infuse Disney Parks with pop culture. It was his (controversial!) vision that Disney Parks should be places for people to encounter the characters, stories, and stars that mattered to modern audiences — to “ride the movies!” The trouble was, Disney wasn’t making many movies worth “riding” at the time. But someone was…

In the 1980s, no one was shaping pop culture like George Lucas, the visionary creator of Star Wars. As luck would have it, Lucas’ second pop culture coup had been the introduction of Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark — a film Eisner himself had greenlit while back at Paramount Pictures. So it’s no surprise that, in an effort to infuse more meaningful pop into Disney Parks, Eisner managed to broker an unprecedented deal with George Lucas to put his talents (and teams) to work for Disney Parks.

In an effort to fast-track more pop-friendly projects for Disney Parks, Lucas was brought into a pop culture powerhouse production — at the time, the most expensive film per-minute of any ever made; part music video, part sci-fi adventure; combining cutting-edge 3D technology with unprecedented in-theater effects… We can only be talking about the Lost Legend: Captain EO, a musical extravaganza melding Lucas’ production with the direction of Francis Ford Coppola (director of The Godfather) and the unrelenting star power of the world’s biggest celebrity at the time, Michael Jackson. Captain EO was a bold, brash, expensive, and pop-infused example of what Disney Parks would become.

Captain EO was followed in quick succession but another stellar E-Ticket — a ride that would literally change Disney Parks forever: the Lost Legends: Star Tours. In fact, this simulator serves as the pivot point in two of our in-depth industry insider stories: the Age of the Simulator and the “Ride the Movies” era. Star Tours singlehandedly signaled that the pop culture transformation of Disney Parks was underway while unthinkably inserting cool, modern, hip characters into the parks, even if they weren’t Disney characters.

Just two years later, Disney’s Hollywood Studios opened with a stunt show based on Lucas’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Indiana Jones popped up again in his own dark-natured, cinematic ride through the Modern Marvel: Temple of the Forbidden Eye in Disneyland in 1995.

But the groundwork was set: Disney Parks didn’t have to be just for children. Using advancing technology, Eisner’s cinematic spin, and a proven model of licensing external properties for use within the parks, Imagineering was unleashed. Now that Disney Parks could host elaborate, expensive, and modern stories, a whole new catalogue of ideas began to develop. And that’s where the path to Alien Encounter really begins.

Extraterrestrial inspiration

Flash back briefly to a decade before Star Tours’ debut — the 1977 premier of the first Star Wars film. In some ways, the debut of Star Wars had relaunched the Space Race. But this time, it wasn’t coordinated by NASA and delivered via rockets. Instead, film studios were suddenly willing to invest big time in a genre that had been declining for decades: science fiction.

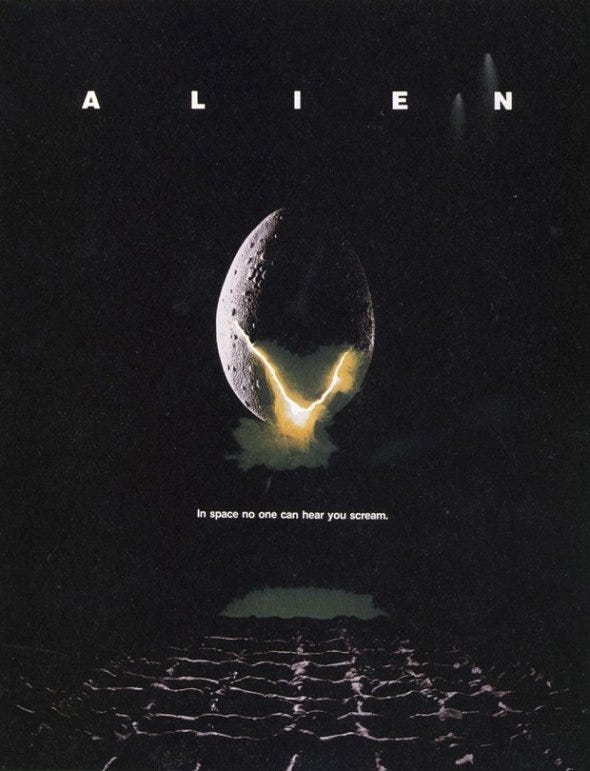

Studios raced to find their own sci-fi counterpart to Star Wars (see Disney’s The Black Hole, cited earlier for its disastrous box office). Though 20th Century Fox had distributed Star Wars itself, they still moved ahead with a space-set sci-fi follow-up: 1979’s Alien.

When Alien debuted in 1979, critical reception was mixed. But the film was positioned at the forefront of a resurgence of sci-fi, and it offered something Star Wars didn’t: terror. Reflecting on a screening of the film in Dallas, Texas, editor Terry Rawlings recalled in The Beast Within: The Making of Alien:

“It was the most incredible preview I’ve ever been in. I mean, people were screaming and running out of the theater.”

Suffice it to say, Alien was a generation-defining horror film in the vein of Jaws. The R-rated feature won an Academy Award for its special effects, trapping guests aboard the spaceship Nostromo as an unstoppable terror is set loose on board. Born of a parasitic “Facehugger” depositing an embryo down the throat of an unwitting crew member (and eventually bursting out of his chest), the monstrous creature became an iconic figure in cinema; so much so that Alien was selected for preservation in the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Speaking of which, those instantly-recognizable aliens — Internecivus raptus, common name Xenomorphs — stand in the pantheon of horror movie creatures… Hideous, skeletal, eyeless, biomechanical creature with elongated skulls, retractable inner pharyngeal jaws, slimey drool, acidic blood, and barbed tails. Unlike the intelligent, technological, ritualistic, humanoid hunters of 1987’s Predator, the Xenomorphs aliens are primal, hissing, insectoid animals driven by instinct — more interested in eating than invading.

Alien also introduced audiences to a very different kind of future than the prevailing image of the ’60s and ’70s. Whereas gleaming white spaceships, Lycra space suits, and pastel mid-century optimism had been the norm prior, Alien took shape around the amoral Weyland-Yutani mega-corporation; in a hissing, industrial, claustrophobic spaceship with labyrinthine corridors; a dark, corroded, future of rusted ships and frazzling technology…

Perhaps all of that makes it sound even more unexpected that Imagineers were tasked with creating a dark ride experience that would envelope the audience into the world of Alien. Yet that attraction — allegedly to be called “Nostromo” — would’ve placed guests aboard the faltering space tug of the same name, arming guests with laser guns, as Audio-Animatronic Xenomorphs attacked from the shadows and leaping Facehuggers burst from eggs.

As the story goes, senior Imagineers were horrified by the idea that Disney Parks would bring an R-rated film to life. Imagine it: the spider-like Facehugger aliens that implant exterrestrial embryos down the throat of unwilling human hosts; juvenile Xenomorphs bursting out of their host’s chest cavity; nudity and sexual undertones; cursing. Alien was just too intense, they argued.

And if you can imagine, those senior designers also balked at the idea of arming guests — especially young ones — with guns and telling them to shoot them during the ride. (This fear, we now see, they managed to get over.) Allegedly, these long-standing designers had a few heart-to-hearts with Eisner, eventually convincing him that the Alien shooting dark ride was simply not right for Disney Parks. Eisner relented and allowed the project to die.

However, the story doesn’t end there… a young group of upstart Imagineers was enthralled by the idea of a dark and sincerely gritty Disney ride, complementing Eisner’s “Ride the Movies” mantra in transforming Disney Parks… In secret, they began to develop a plan to move forward with bringing Alien to life, and their idea would cast the ride in an even more sinister tone that would make the controversial shooting dark ride look like a walk in the park…