Universal had been thinking about building a park in Orlando since 1982, but the idea had always stalled as Universal had never built an intentional, master-planned theme park before (having only gradually turned their working Universal Studios Hollywood into a theme park via the Studio Tour and its later accessory attractions).

If Universal was determined to build in Disney World’s backyard, they needed a heavy-hitter… a must-see E-Ticket that could make this new Universal park a contender, even against a much-larger adversary. But Spielberg’s 1986 ride on STAR TOURS and his ensuing consideration of a Back to the Future ride changed that, and made it seem possible that this new kind of simulator could be Universal’s secret weapon….

Not-so-secret

Speaking of secrets, Universal’s ambitions in Orlando weren’t one.

As a matter of fact, Disney’s CEO Michael Eisner knew full well of Universal’s plans for a Floridian studio park (perhaps as a result of his time at Paramount), and he was determined to outwit them. This is the part of the tale where the history of Unviersal Studios Florida merges briefly with that of Walt Disney World. Eisner – again drawing from his filmmaking roots and entertainment industry connections – decided to keep Universal out of Central Florida with a preemptive strike.

Before ground could move on the proposed Universal Studios Florida, Eisner announced that Walt Disney World would undergo an unprecedented expansion, growing the proposed Lost Legend: The Great Movie Ride from an EPCOT Center pavilion into an entire third park. The Disney-MGM Studios would be a fusion theme park / working movie studio, and its headlining ride would be – you guessed it – a tram-led studio tour through the park’s real production facilities and staged special effects encounters.

Having stolen their bread-and-butter studio tour, Eisner must’ve thought that Universal would relent and cancel their studio park in Orlando. Instead, they doubled down.

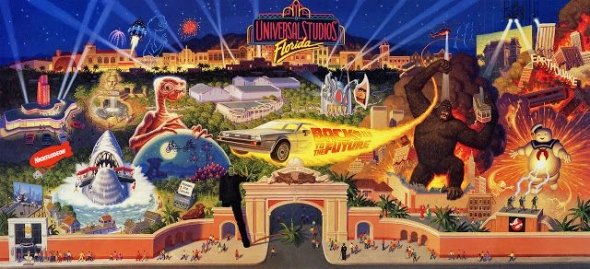

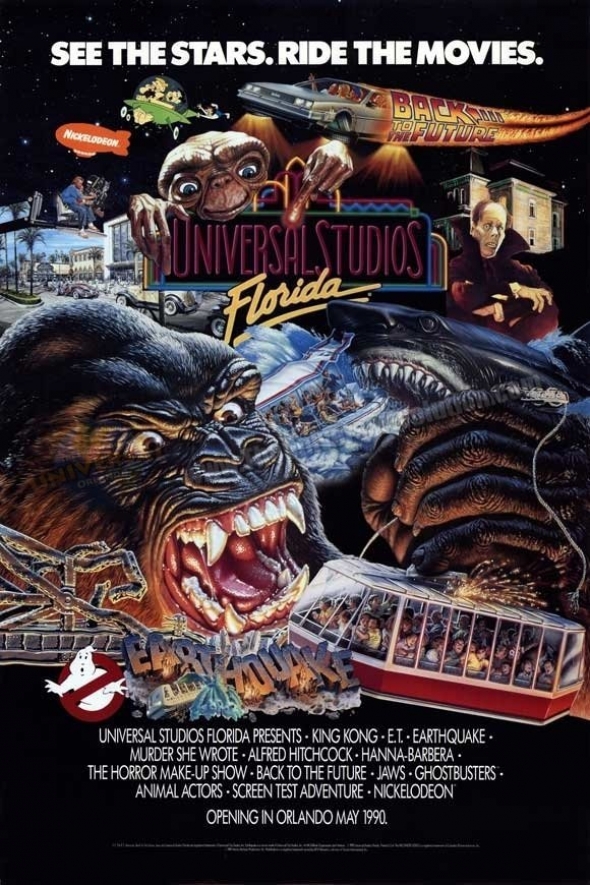

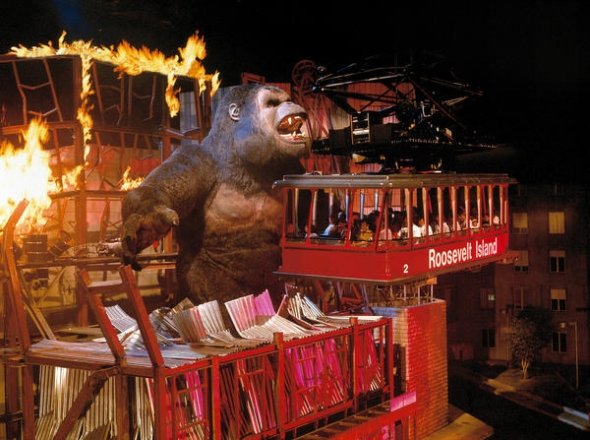

Brilliantly, Universal sliced away the individual elements and encounters of Hollywood’s Studio Tour and built each one out into a full-fledged, standalone attractions based on Earthquake, King Kong, and Jaws.

Opening… almost

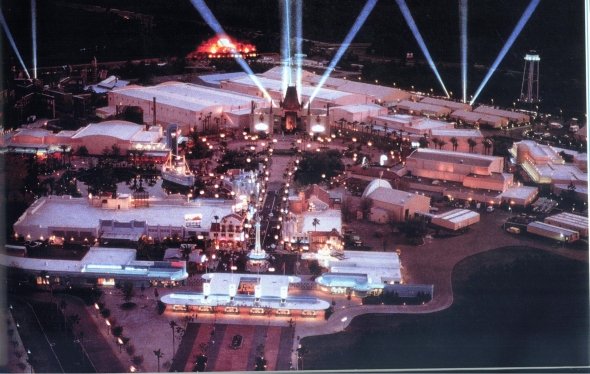

Universal Studios Florida opened June 7, 1990.

Not since Disneyland’s infamous “Black Sunday” had an opening gone so awry.

Universal’s plan to build a park filled almost exclusively with showstopping E-Ticket attractions based on the Hollywood Studio Tour’s segments was brilliant, but perhaps overly ambitious.

Just hours before Steven Spielberg cut the ribbon and welcomed guests into the brand new park, a massive power-outage frazzled the (at the time) cutting edge computers that managed the special effects on Earthquake: The Big One.

Meanwhile, the park’s starring Lost Legend: Kongfrontation was even more complex. The “talkback” software that communicated between the massive animatronic Kong and the ride vehicles was still not operating properly after weeks of testing, which meant the Kong figure had to be operated manually (or risk passing into the vehicle’s ride path too early, causing a collision). In a ride packed with dangerous special effects, a short-circuiting computer control left Kong closed most of the day.

The Jaws ride was famously plagued with technical problems galore (to the extent that it eventually closed entirely and was literally redesigned and rebuilt from scratch, only “officially” opening years later, as detailed in its own in-depth Lost Legends: JAWS entry), and immenent Floridian thunderstorms kept the ride closed most of opening day.

Put simply, Universal had banked on a “big 3” collection of movie-themed thrills, and all three were unmitigated disasters.

Smartly, Universal determined that it had a lot of work to do, and officially pushed back the opening of the would-be park headliner based on Back to the Future. They simply couldn’t afford another disastrous opening, so the expected January debut was pushed back to May 1991 – nearly the park’s first anniversary. Because as formidible as animatronic apes, waterlogged sharks, and cutting-edge special effects had been, the sheer technological brilliance of Back to the Future: The Ride would surpass them all…

Behind-the-ride

During initial planning meetings in 1988, it was suggested that a roller coaster ride “back to the future” would be a surefire way to bring thrillseekers (and Disney’s oft-neglected teenage demographic) racing to Universal Studios. However, the plan suffered from the same downfalls that had grounded a potential Star Wars coaster at Disney Parks: a long lead time, and a ride too fast to convey any sense of story.

It was George Lucas’ comments about his Disney-delivered Star Tours simulator that had so inspired Universal to push farther, so perhaps appropriately, they decided that a simulator of their own would be the answer. But how to create an innovative, technological attraction to surpass Disney’s? How could guests feel as if they were seated in the film’s famous DeLorean DMC-12 time machine? Surely not in a 40-person simulator pod… In fact, the answer was more than a decade old…

In the early 1970s, the San Diego Hall of Science (now the Fleet Science Center) began searching for a film format to project in their 76-foot tilted dome Planetarium. IMAX Corporation stepped forward, creating a new kind of projection technology. OMNIMAX premiered in San Diego in 1973, distorting a projected image to wrap around viewers, across the inside of a domed surface. OMNIMAX (today called Imax Dome) fills viewers’ peripheral vision, creating an immersive, wraparound view that’s convincingly real. The novel technology has become a mainstay of science centers.

Universal’s plan was brilliant. Twelve ride vehicles (each a “new, eight-passenger convertible DeLorean model”) would be divided across three tiers, placed in “garages” under a dark, 85-foot OMNIMAX screen, as this Passholder-exclusive patent displays.

Then, each vehicle would simultaneously be lifted eight feet out of the “garage” and into the dome, where a three-piston motion base attached to each would allow it to rise, fall, and buck along to a projected ride video. Most astounding of all, each DeLorean would be precisely positioned so that, once they rose out of the garage, riders would be unable to see any other vehicle, making it seem as if this massive, all-encompassing, larger-than-life experience was happening just for them!

The ride under construction at Universal Studios Florida (and concurrently at Universal Studios Hollywood, aiming for a co-opening that would eventually be delayed two years due to foundation issues) would double the arrangement, with two OMNIMAX domes, a total of 24 DeLoreans, and a fool-proof plan: even if one dome went down for technical difficulties, the other could continue so that the ride would rarely (if ever!) need to be closed completely.

Add in special effects genius Doug Trumbull (the force behind 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind). Trumbull was brought on to deal with production problems cropping up in the making of Back to the Future: The Ride and singlehandledly shaped the project into the Lost Legend we know: a technological, cinematic marvel that put Universal Studios on the map.

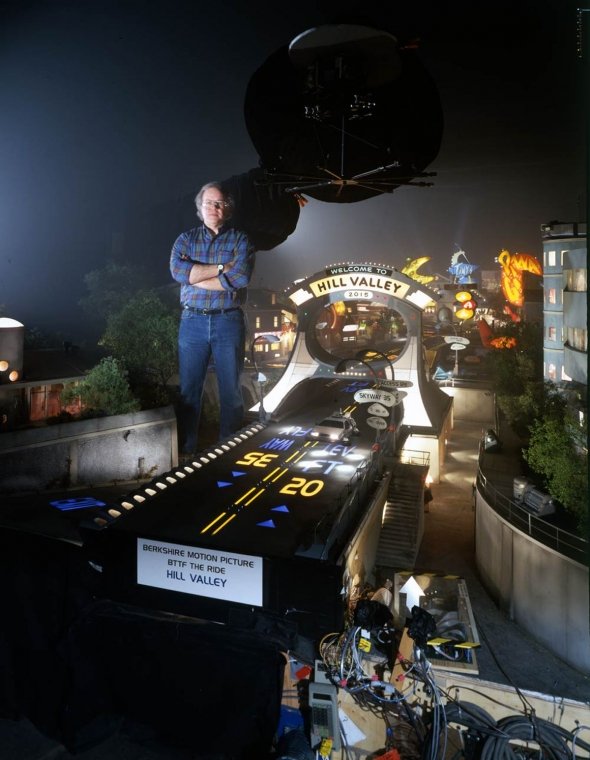

Using scaled miniature sets (the same filmography technique used to bring Star Tours to life), Trumbull oversaw the creation of the 4-minute ride film (shot on 70mm film).

From concept to opening, the five-year project topped $40 million. However, when Back to the Future: The Ride opened on May 2, 1991, it kicked off a blockbuster summer season during which Universal Studios Florida beat the Disney-MGM Studios’ attendance numbers… no small feat after the disastrous opening of “the little park that could.”

So what did guests find inside the Insistute of Future Technology? On the next page, we’ll step inside and take a historic turn on Back to the Future: The Ride.