Discovery declines

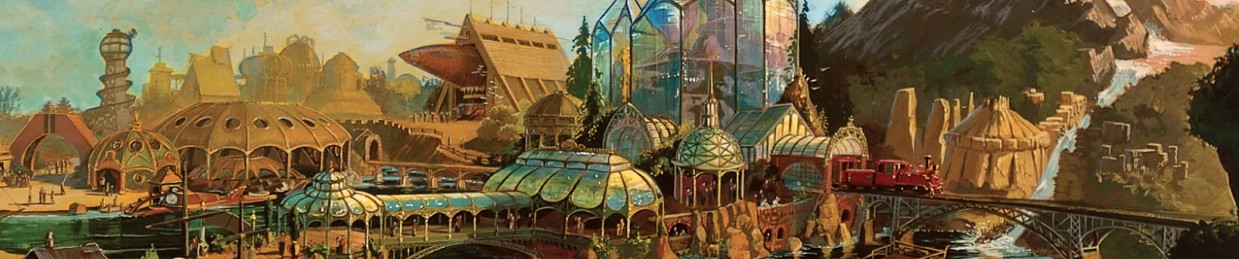

Discovery Bay was officially announced via a memo in October 1976. A scale model of the park expansion was then built and displayed inside of the Preview Center on Main Street, U.S.A. that same year. It was official, and Tony Baxter’s Discovery Bay would become the eighth land at Disneyland Park in California.

As we all know, Discovery Bay never materialized on the shores of the Rivers of America. As with all forgotten projects at Disney Parks, the reasons are numerous. Here are three of the major reasons.

1. Prioritizing projects

As the ’70s progressed, the cash-strapped Disney diverted its money and Imagineers to two massive projects: Walt Disney World’s EPCOT Center and the brand-new Tokyo Disneyland in Japan. Manpower and creative talents were absorbed by the two parks. That’s why the ’70s today are often remembered as Disney’s decade of fairly inexpensive steel coasters rather than the epic dark rides of the ’60s or the “Ride the Movies” E-Tickets that would follow in the ’80s and ’90s.

Given that Disney’s few resources were funneled into the projects they had to complete, it’s easy to imagine how Discovery Bay would’ve felt a tad too extravagant for the era.

2. The Island at the Top of the World

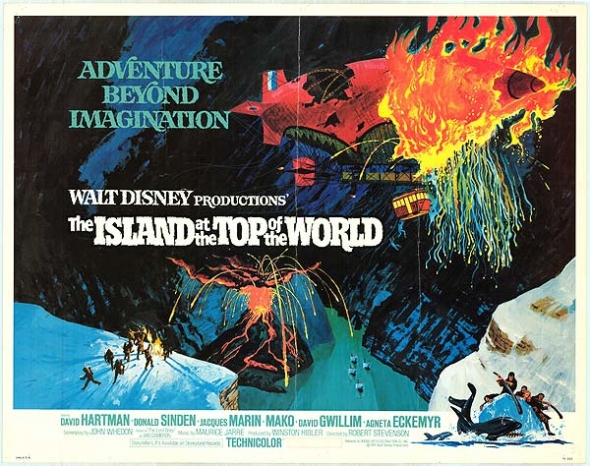

Remember how 1954’s 20,000 Leagues had kicked off not just an era of Jules Verne fantasy adventure adaptations, but the replacement of Westerns as the prevailing genre in pop culture? Though Disney was in the midst of the “Dark Ages” after Walt’s death in 1966, they went big on a return to the genre with 1974’s The Island at the Top of the World. An original story (but clearly cut from the same cloth as a Verne adventure), the film was meant as a return to form for the studio, and a triumphant special-effects filled sci-fi fantasy picture.

The Island at the Top of the World got a lot right: a Victorian setting, a compelling team of aristocratic “adventurers,” an exceptional vehicle (the Hyperion Airship, designed by Disney’s Peter Ellenshaw), and a Verne-style journey to the Graveyard of the Whales and the remote volcanic Viking island of Astragard, hidden behind the mists of the impenetrable Arctic for centuries. Still, the ingredients didn’t mix properly. Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film one-and-a-half stars and called it “a 20,000 Leagues rip-off.”

Earning just $10 million against its $8 million budget, the film’s abysmal performance at the box office and lukewarm reviews during its 1974 debut cooled executives’ reactions to Discovery Bay. While the land didn’t need a runaway box-office success to justify its construction like we might picture today, a very clear box office failure certainly weighed against the land’s likelihood.

Times had changed… again. Though 20,000 Leagues had begun the sci-fi fantasy blockbuster era two decades earlier, Island at the Top of the World marked its end… the movie is remembered as the last big budget adventure film of the era. Why?

3. Pop culture strikes back

The failure of Island at the Top of the World might’ve changed filmmakers’ tastes, too, which consequently changed the kinds of movies that major studios filmed. Baxter commented on the Season Pass Podcast, “People are so skittish that instead of saying ‘We did a bad Jules Verne movie,’ they go ‘Well, people don’t want to see Jules Verne movies.’” As a result, fantasy was largely retired.

Luckily for filmmakers, something did come around to reinvigorate a new genre of films. The year after Discovery Bay’s would-be-opening, STAR WARS debuted. The era of fantasy adventure, fantastic vehicles, and time travel films was usurped by the “Space Western” as sci-fi became the taste of the public.

(And interestingly, it was Tony Baxter himself who pushed throughout the 1980s for Disney to work out a deal with creator George Lucas on incorporating Star Wars into Disney Parks from the get-go. Not coincidentally, Tony was the lead Imagineer on the Lost Legend: STAR TOURS, recalled today as the start of the “Ride the Movies” era and the Age of the Simulator; a major pivot point in the story of Imagineering and Disney Parks…)

Second lease

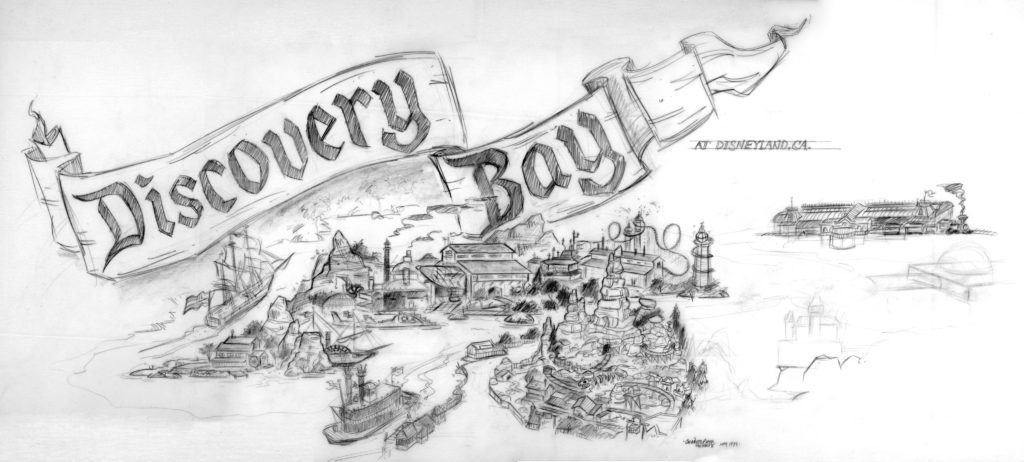

Two decades after Discovery Bay had been first proposed – a version of the land reportedly returned to the table. The sketch above by former Imagineer (and noted author of Knott’s Preserved, Pacific Ocean Park, and Marc Davis In His Own Words) Chris Merritt was reportedly created at Tony Baxter’s request. It represents a distinctly 21st century reimagining of the Discovery Bay concept cooked up in the late ’90s.

At least in this ’90s iteration of the land, Discovery Bay wasn’t necessarily expected to take shape on the “Discovery Bay expansion pad” at all. Instead, a sort of “mini-land” version of DiscoveryBay would’ve actually been built on the unused northern half of Tom Sawyer Island, as Park Lore Members can see in the ’98 Los Angeles Times article below….

Access this island-set version of the land would likely have meant a permanent bridge built across the Rivers of America from Frontierland, permanently docking the Mark Twain (as a restaurant in New Orleans Square) and the Sailing Ship Columbia (as a walkthrough in Discovery Bay). For the most part, this Discovery Bay would’ve largely been a placemaking project all meant to support the addition of the E-Ticket Geyser Mountain – a ride we detailed in our Possibilityland: Never-Built Mountains feature.

Though Disney denied at the time that Discovery Bay was being rebooted at Imagineering, the timeline makes sense. Around the New Millennium, Disneyland was suffering from the disappointing opening of the Declassified Disaster: New Tomorrowland ’98, the closure of the Submarine Voyage, and an era of major cost-cutting. The “Discovery Bay 2.0” project and its centerpiece Geyser Mountain would have been envisioned as a much-needed boost to Disneyland’s linup, steeling the park against the soon-to-arrive California Adventure (which, of course, was expected to be so new and so cool, boring ole’ Disneyland would be a ghost town). Obviously, that didn’t quite come to pass.

So despite its prominent placement and being one of the few available expansion pads in the otherwise-landlocked Disneyland, the plot of land once envisioned as the home of Discovery Bay remained available for decades, housing only the park’s Big Thunder Ranch petting zoo and, later, a temporary amphitheater.

Especially by the 2010s (after the Wizarding World’s runaway success) it seemed that every time Disney released a blockbuster-budget film, rumors swirled that Imagineers had been put to work on designing a complementary land to fill the Discovery Bay plot. First it was Oz The Great and Powerful (with rumors of the land becoming the city of Oz, and a Kansas carnival as the transition from Frontierland). When that movie failed to meet expectations, rumors said that the plot could instead be used for an expansion of Frontierland based on The Lone Ranger. Of course, that film fared even worse.

But in 2012, Disney finally acquired their Wizarding World-ready blockbuster…

From Bay to Batuu

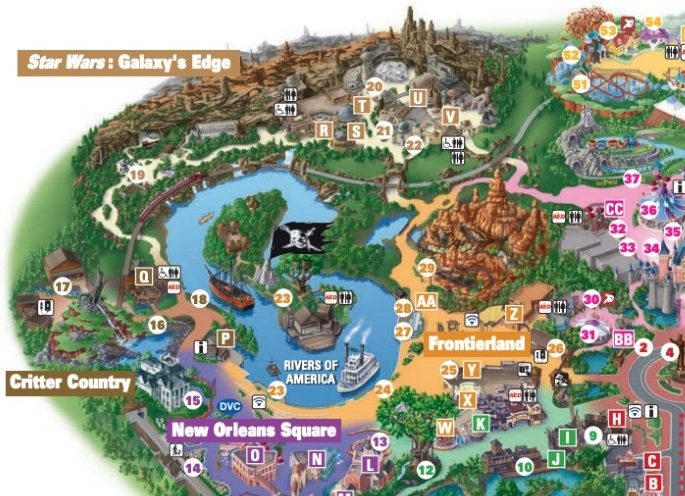

The $4 billion acquisition of Lucasfilm finally put Disney in charge of Star Wars. Yes, the sci-fi “Space Western” that had definitively ended the age of the fantasy film and had marked the shift away from The Island at the Top of the World in the ’70s would now take Discovery Bay’s spot on the northern edge of the Rivers of America…

Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge would be immersive and cinematic in a way only the best “living lands” are, built of an immense scale, bringing to life a completely original world and a master-planned mythology tied into the epic Star Wars universe.

Naturally, it wouldn’t exactly make sense for the distant planet of Batuu and its impoverished Black Spire Outpost traders’ market to actually join the Rivers of America with sailing ships and paddlewheelers churning by, so Disneyland’s River underwent a major reshaping and shortening, with a veritable mountain range of Western cascades, native settlements, and a rerouted Disneyland Railroad along its new northern edge.

The clever new backdrop both improved the Rivers of America and served as a cloaking device, concealing the alien planet of Batuu from the rest of the park and vice versa.

Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge is, by all accounts, a very worthy project for taking on the Discovery Bay parcel. In many ways, it’s a pinnacle of Imagineering, and constructed on a scale practically no other “living land” can match. It’s a billion dollar project in itself, astounding in every way.

Of course, subjectively, many fans note that Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge is wildly out-of-scale for Disneyland’s storybook proportions; the 14-acre land is larger than any other, built of a different time, design aesthetic, and philosophy such that it sticks out like a sore thumb. It’s the only one of the park’s lands to diverge from Disneyland’s practically-patented process of passing content through a lens of romanticism; the only land dedicated to a single intellectual property rather than a literary genre; the only one separated from the rest of the park by its own berm, and operated by its own in-universe immersion and rules.

As you can imagine, there’s no single defining reason why Discovery Bay was canned, and its eventual replacement in Galaxy’s Edge is a leap forward Tony Baxter couldn’t have imagined. But even if the land never materialized, that doesn’t mean that it disappeared forever. On the last page, we’ll discuss the legacy of Discovery Bay… where its pieces and parts were scattered to and what we hope to see of it in the future…