To stand on the grounds of Disney’s Village Resort in 1985, you’d find yourself still in the midst of a wooded, swampy land dotted with villas, but otherwise reminiscent of the “real” Florida and the Walt Disney World of the ’70s that promised a retreat from the real world. But things were about to change significantly.

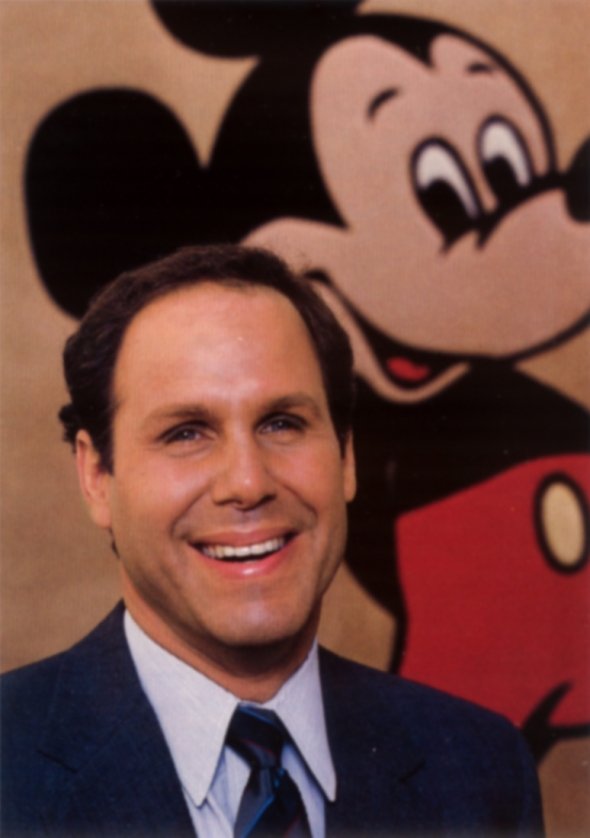

We’ve spent plenty of time in our Lost Legends series exploring the absolutely transformative early legacy of CEO Michael Eisner, who joined Disney in 1984 as a last ditch effort to save the company after the disastrous ’70s.

Yes, it was Eisner who led revolutions of Disney’s live action studios; who kicked off the Disney Renaissance in animation; who boldly reinvented Disney’s theme parks with the controversial choices we chronicled in an in-depth Special Feature on the “Ride the Movies” era; who literally transformed Walt Disney Productions into the multi-faceted Walt Disney Company, paving the way for the today’s media-conglomerate with high-profile acquisitions (like ABC, ESPN, and The Muppets).

But right off the bat, one of Eisner’s more radical roles was in reimagining Disney’s Florida property again. At least for the subject of today’s story, one of the highlights of that redefining of Walt Disney World would be inspired by a family vacation…

The Chautauqua spark

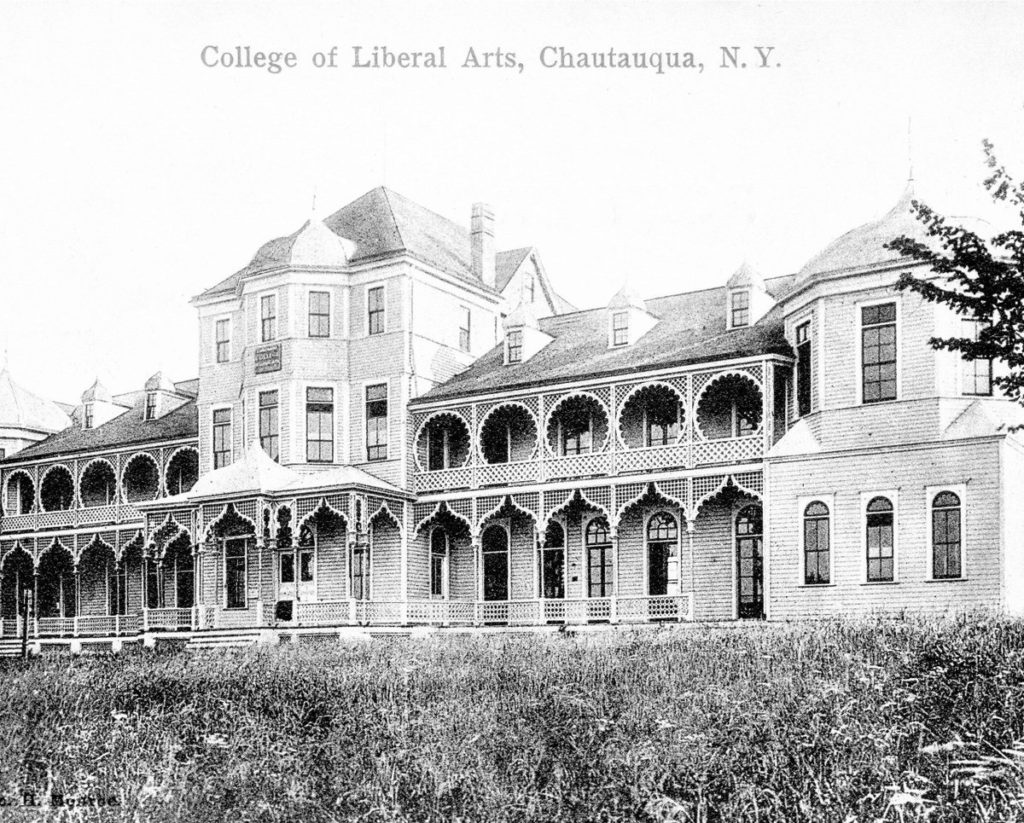

Located on the shores of the Chautauqua (sheh-TAW-kwah) Lake in western New York (between Buffalo and Erie, Pennsylania), the first meeting of the New York Chautauqua Assembly occured in 1874. Co-created by Methodist minister John Heyl Vincent, the Chautauqua Assembly was a nondenominational teaching academy, meant to train Sunday school teachers in Vincent’s clever, outdoor, summer camp-style format.

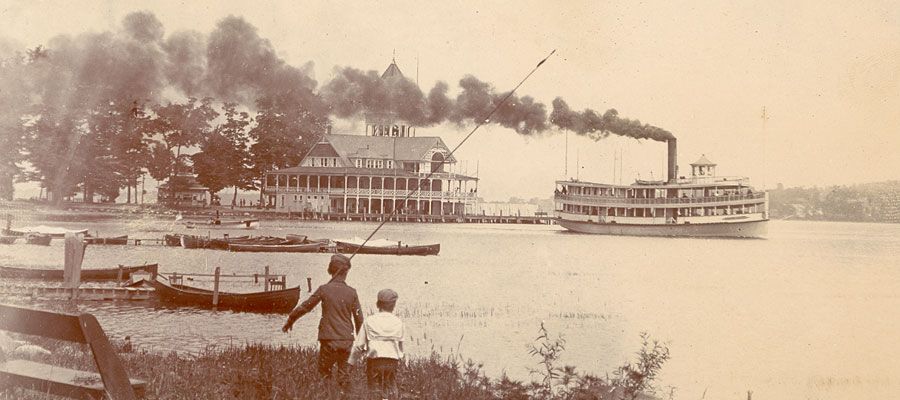

Within a few years, however, its scope had broaded. By the 1880s, Chautauqua was gaining national recognition for its summertime offerings, when residents and visitors arriving via steamboat gathered in the thousands for concerts, social activities, and informal courses in the arts and public affairs. With both in-person experiences and cutting-edge correspondence courses, Chautauqua brought “a college mindset” to working class adults in a time when the spread of information was slow, laborious, and reserved for the elite.

By the end of the 19th century, Chautauqua had gained national recognition for its grassroots classes and noted speakers in the high-brow fields of civic engagement and self-improvement. In many ways, Chautauqua’s summer programs in the arts, relligion, education, and music “democratized” education and brought new knowledge to the people.

The lakeside village became a summer retreat for turn-of-the-century East Coast travelers. The town’s transformation into a learning campus continued year after year, as historic hotels, inns, amphitheaters, halls, and schools were constructed to host classes for everyday people looking for new experiences. In an era when emerging railroad lines made travel faster and easier than ever, Chautauqua became a summertime destination, drawing thousands to its season-long learning festival.

Chautauqua wasn’t just a place; it was a movement.

Grassroots Chautauqua Assemblies spread throughout the United States during the next half-century. Through the 1920s, Chautauqua-inspired educational gatherings became cultural events in midwest downtowns, city parks, rural assembly houses, and more. President Theodore Roosevelt called the Chautauqua movement, “the most American thing in America.” Chautauqua had become the TED Talk of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, through the mid-1900s, Chautauqua’s New York lakeside campus was growing into a summer recreation resort for artists, thinkers, writers, families, sophisticates, and adventurers who sought to learn new trades, hear from great politicians and writers, and pursue niche interests.

One of those thinkers was then-new CEO of Walt Disney Productions Michael Eisner. In fact, by the time of Eisner’s visit to Chautauqua in 1985, the resort had well and truly blossomed into a sprawling, 2,000 acre campus; a self-contained and gated property of meeting halls, amphitheaters, cottages, green spaces, recital halls, libraries, and watercraft launches existing for the express purpose of becoming a haven of lifelong learning each summer.

Then, as now, when the season arrives, Chautauqua springs to life. Visitors can purchase day- or week-long passes into the lakeside village for an all-you-can-learn buffet of classes, presentations, speakers, and more. Some guests stay “on-property” at the iconic Athenaeum Hotel (above) while others settle into historic boarding houses, townhomes, cottages, and bed-and-breakfasts, entering the Chautauqua Institute each day.

Chautauqua’s summer season isn’t just filled with opportunities to absorb information from politicians, speakers, orchestras, forums, masterclasses, and seminars; it’s hands-on, allowing guests to register for courses and live their dreams to try out painting, dancing, musical instruments, sports, sailing, pottery, acting… You can even join season-long Festival Schools – summer-long residency training programs complete with room and board in the campus’ residence halls!

With classes for all ages from preschool onward, this annual summer retreat has been a tradition for generations. For the day guest, the weeklong student, or residency school participants, Chautauqua is a Burning Man for learning… er… Learning Man? It’s a classic New England getaway and sophisticate’s paradise. You can imagine, then, how after a particularly enlightening visit to the Chautauqua Institute with his own family, Michael Eisner had one of his familiar sparks of inspiration. In short: “Disney could this.”

A Whole New Walt Disney World

Eisner must have returned from his Chautauqua Institute visit reenergized and ready to tackle the transformation of Walt Disney World. With billionaire Texas oil baron Sid Bass (and his 25% stock ownership of Disney) on board, Eisner masterminded a new business model for Orlando.

It’s often said that as far as the Disney Parks, Experiences, and Products division is concerned, theme parks are actually Disney’s secondary interest in Central Florida… The property’s primary business? Real estate, rentals, and – yes – hotels. Think about it: Despite being ret-conned as Disney World’s “signature” hotel, the Grand Floridian only came online in 1988 – the first in Eisner’s lineup of extravagent, opulent, and over-the-top resort properties. It was followed by the Beach Club, the Yacht Club, and the cleverly-moderate Caribbean Beach. Waves of hotel inventory expansion would follow, with increasingly ambitious concepts helmed by world-renowned architects.

But, prompted by an early hint from Bass, Eisner had particular interest in activating on all the space around the Walt Disney World Village and the Village Resort.

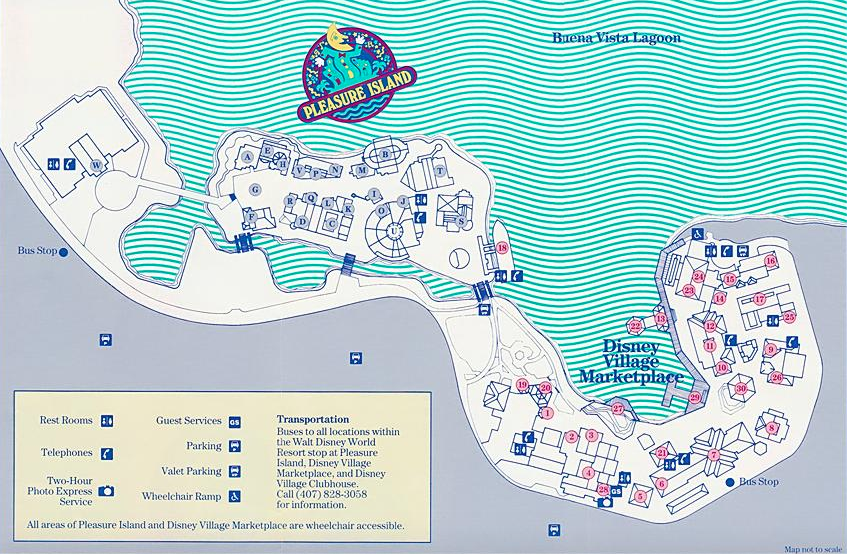

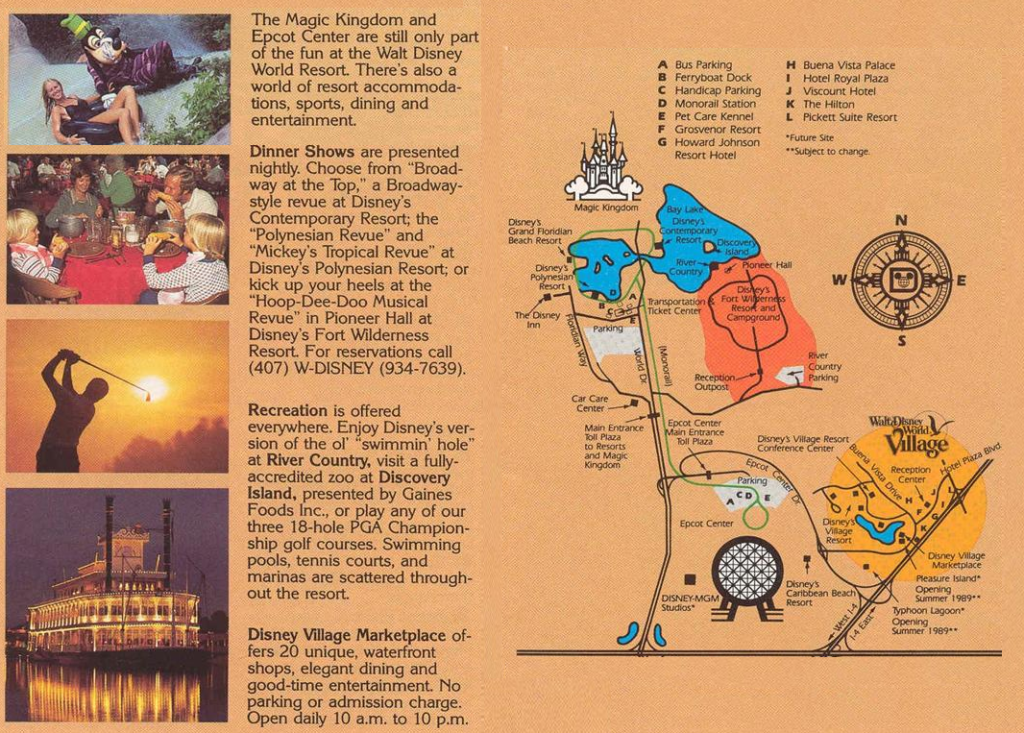

It began when, in 1989, the shopping village (renamed the Disney Village Marketplace) was joined by the much more contemporary Pleasure Island – a nighttime paradise of adult-oriented dance clubs, bars, immersive theaters, and restaurants (like the Lost Legend: The Adventurers Club) born of the “Ride the Movies” era and packed with cinematic splendor.

Pleasure Island and the reinvigorated Disney Village Marketplace turned the sleepy, wooded, and once-remote area into a glowing, neon tourist centerpiece complete with nightly fireworks. The Village Resort was suddenly prime real estate.

At the same time, construction was underway on no less than three resort hotels that would take shape in the area… A canal carved northwest out of the lake that had once merely meandered into the wooded wilderness past the Treehouse Villas now gained boat traffic. The waterways connected a new dock serving the Marketplace Village and Pleasure Island to those three hotels: Disney’s Port Orleans, Disney’s Dixie Landings (today, Port Orleans Riverside), and the timeshare-based Disney Vacation Club (today, Old Key West), all premiering by 1992.

So standing in Disney’s Village Resort now, you’d find yourself in a very different place: across the lake from the neon Pleasure Island and downriver from increasingly sprawling and ornate resorts. By all accounts, prime real estate.

Meanwhile, by the dawn of the ’90s, Disney was in a very different place than it had been a decade earlier… Eisner’s high-profile transformation of Walt Disney World was a resounding success; the Disney Renaissance had revived the company’s finances (and its reputation); the epic additions of the “Ride the Movies” era had made Disney’s parks more popular than ever. So finally, it was time to active on Eisner’s big idea. Step inside on the next page…