The smell of wood – decades-old, cut, stacked, and bolted, bathed in and baked by summer sun; the aroma of grease, clinging to the lift chain as humming motors drag bug-splattered wooden trains upward, anti-rollback wedges clacking into place in their wake; the roaring, rumbling wave of sound as riders snake along a superstructure of swaying wood beams, shuddering and shaking as up-stop wheels ricochet…

For more than a century, the wooden roller coaster has been a staple of amusement parks the world over. And even once it wooden roller coasters were joined by altogether sleeker, smoother steel sisters throughout the 1960s and ’70s, the wooden roller coasters remained landmarks; classics; essentials.

But in the early 2000s, roller coaster enthusiasts encountered a question they’d never had to ask before: what makes a wooden roller coaster a wooden roller coaster? What if the wood wasn’t aged and hand-sawed, but brand new and laser-cut? What if there were no clack-clack-clack of a classic chain lift? And what if the ride itself were smooth as glass, arcing and slaloming and diving as effortlessly as only a steel coaster once could?

Those were the questions begged by EL TORO at Six Flags Great Adventure. A cutting edge, renegade ride born of the Coaster Wars, this one-of-a-kind-in-the-nation prototype by a bold and brash roller coaster manufacturer set out to rewrite the rules of the wooden roller coaster. Did it succeed? Well… Together, let’s tackle the ups and downs of this fierce and furious thrill ride landmark…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

History in Wood

The story of El Toro really begins with understanding wooden roller coasters – or, as they were known for most of their life, just… roller coasters. Nearly 150 years before the first roller coaster with tubular steel tracks, a first gravity-powered, wood-track-guided amusement ride was thrilling the crème de la crème of French high society.

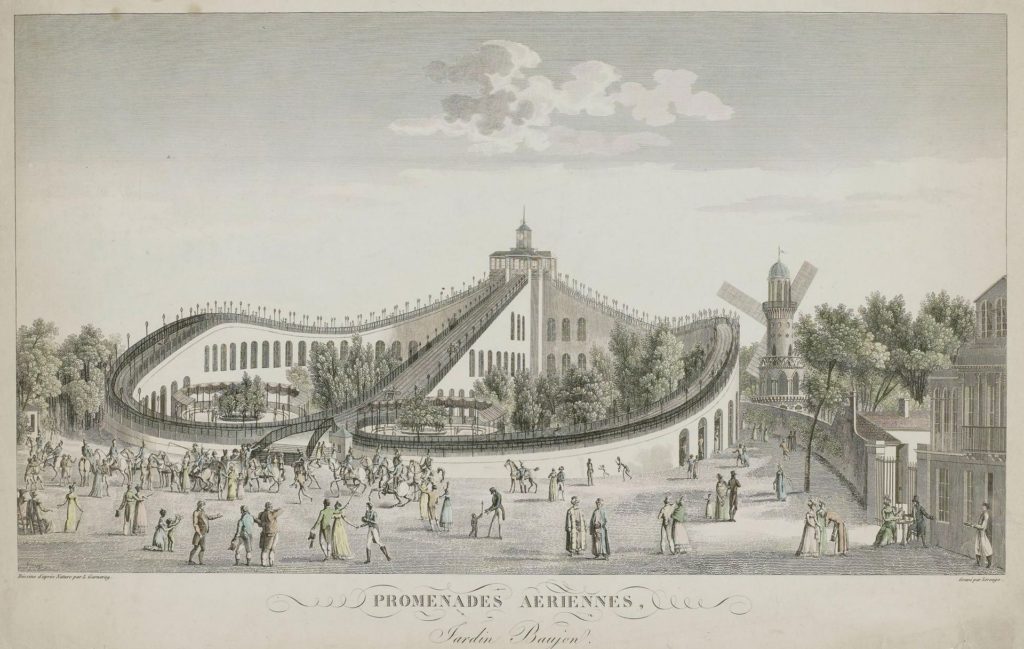

Allegedly devised when – after Napoleon’s defeat – Russian soldiers stationed in France told stories of the carved ice slides back home, the Promenades Aériennes debuted in Paris in 1817 (above). Rather than the Russian’s sled-based winter “mountains” or wheeled summer chutes, the French version used a rope system to tow three-wheeled carts to the top of ornately decorated wooden structures, where aristocrats could strap into carts affixed to the track and coast (relatively) safely down the winding descent.

It was in 1845 that Denmark’s Tivoli Gardens – by most accounts, the first true amusement park and “pleasure garden” – opened, finally allowing everyday people to experience the thrills of a primitive “Russian mountain.” And with the “middle class’s” first taste of gravity-driven thrills, the race was on.

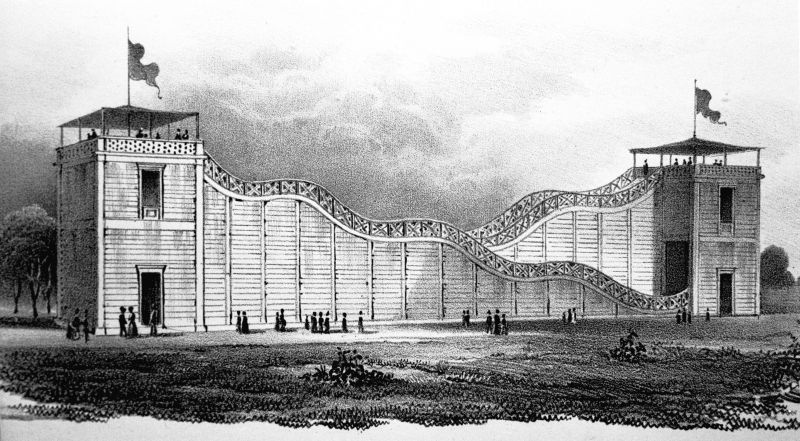

The second half of the 1800s saw “scenic railways” and their successor, “switchback railways” pop up across the globe, becoming mainstays of the era’s coastal boardwalks, picnic parks, and trolley parks. In the so called “Gilded Age” of new earthly delights and amusements, roller coasters became ever more elaborate installations in “pleasure piers” where visitors gathered in awe of funhouses, tunnels of love, and some of the first public displays of the brand new incandescent lightbulb.

Speaking of which, before the first homes in America were even wired for electricity, carnies were already sending riders “looping-the-loops” on crude, early, inverting roller coasters – made, of course, of wood.

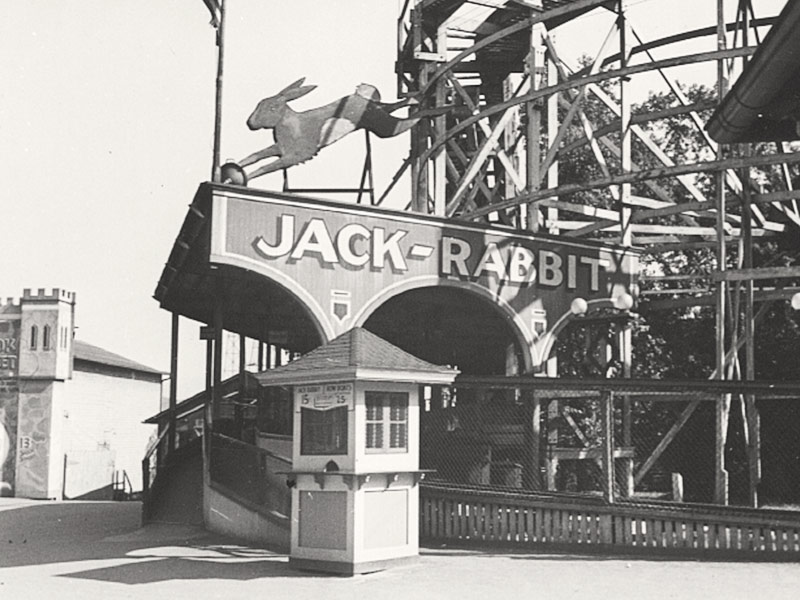

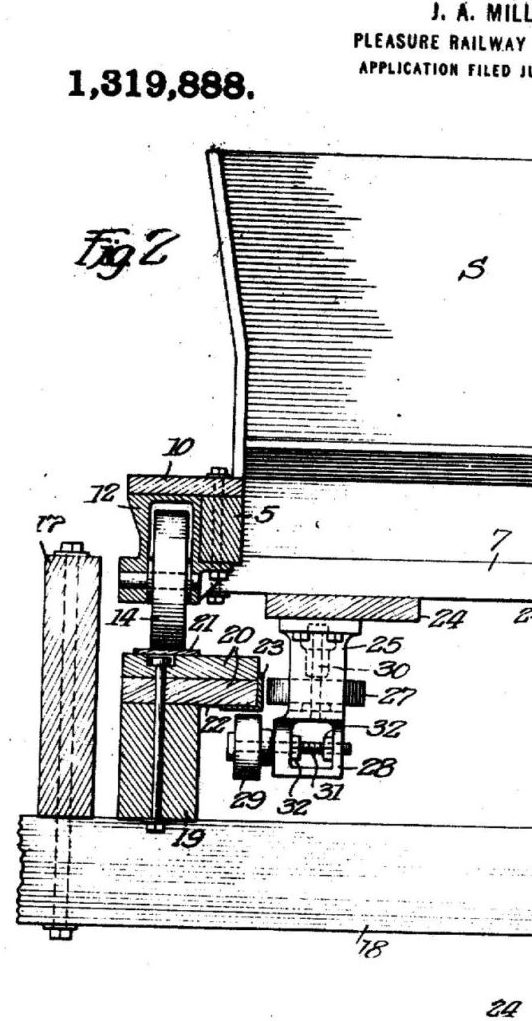

In 1920 – the very same year that the three-lens traffic light was invented – the roller coaster got its real boost and took definitive form. That was thanks to the work of renowned inventor, designer, and builder John Miller. Though Miller already had dozens of coasters to his name, it was reportedly a pair of Jack Rabbits (one at New York’s Seabreeze and another at Pennsylvania’s Kennywood) that Miller debuted a groundbreaking new concept – the “underfriction” or “up-stop” wheel.

As its name implies, the underfriction wheel joined the “road wheels” (riding on a metal strip atop the wooden track) and the “sidefriction wheel” (running along the inside of the rail) to prevent the train from lifting off the track. The underfriction wheel gave the roller coaster incredible new possibilities, allowing it to travel over hills faster than ever with wheels securely fit to the track. Miller was ultimately named on over 100 patents related to the roller coaster, and personally contributed to the design of over 150 rides (with the surviving eight being among the most treasured classics in the industry).

Granted the new, anchoring stability of the up-stop wheel, the Golden Age of the Roller Coaster began in earnest, with increasingly-elaborate “woodies” appearing at picnic parks across the country. Even if the downturn of the Great Depression and World War II in the 1930s and ’40s brought interest in amusements to a sputtering halt, the drought of roller coasters didn’t last forever.

In 1959, the qualifier “wooden” was added to “roller coaster” thanks to the debut of something new: Disneyland’s Matterhorn Bobsleds. Designed by now-legendary coaster manufacturer Arrow Dynamics, the ride was the first to use tubular steel tracks and a computer-controlled system of block brakes, allowing more than one train at a time to safely take to the “slopes.” The Matterhorn might’ve served as a brief reintroduction of the roller coaster after a multi-decade drought… but the true return of the medium wouldn’t happen for another decade…

Resurgence in wood

Especially in the wake of 1971’s Walt Disney World, a whole new generation of “A.D.” (that is, “After Disney”) parks sprung up across the country. This new crop of parks looked a whole lot less like the century-old, slow-growing, organic boardwalks and picnic parks of yesteryear and a whole lot more like the master-planned Magic Kingdom: “Main Streets,” central icons, themed “lands…” and in most cases, roller coasters.

In 1972, Kings Island in Ohio opened with one particularly undisputed highlight: The Racer, designed by John Miller’s protege, John Allen. Though it shared a name with half-century-old classic wooden coasters from the last Golden Age in the 1920s, this modern reimagining was something far greater – the tallest and fastest roller coaster in the world, sure, but more importantly, Kings Island’s Racer was a pivot point. Declared a Roller Coaster Landmark by the American Coasters Enthusiasts, Allen’s Racer is remembered as the spark that lit the “Second Golden Age of the Roller Coaster.”

Now, as a generation of “A.D.” parks sprung to life, wooden coasters found themselves in the midst of a resurgence of their own… alongside their increasingly-competitive steel siblings.

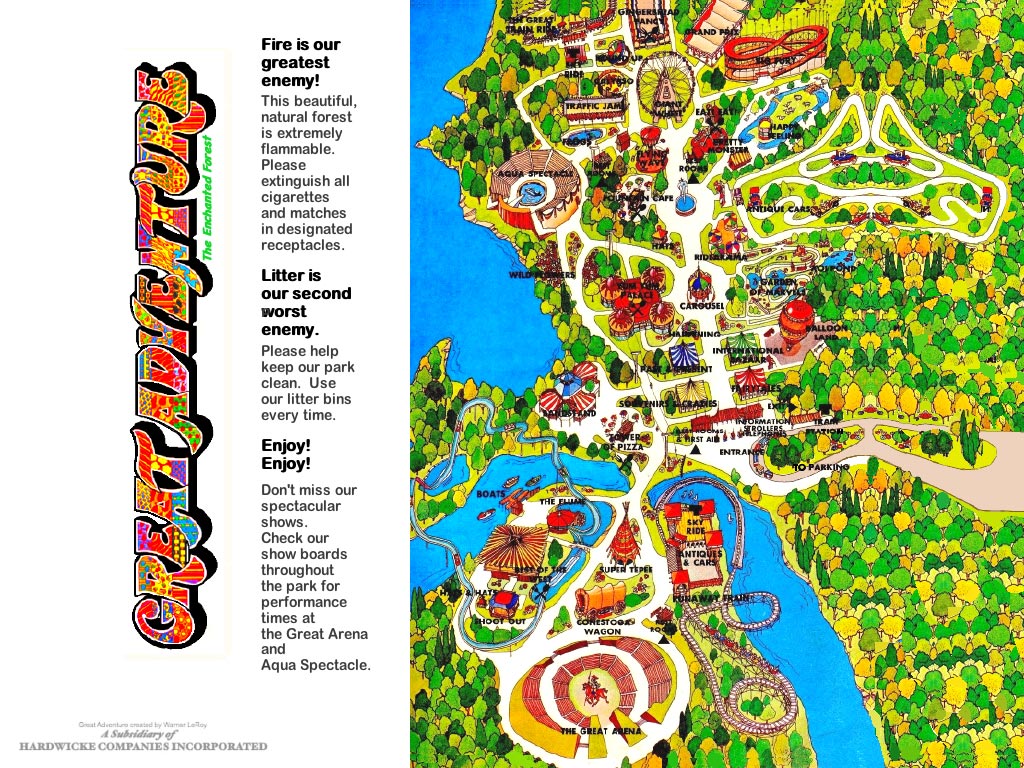

To that end, we might as well shift our focus to the park of interest today: Great Adventure. The brainchild of New York businessman and entrepreneur Warner LeRoy (grandson of Harry Warner – one of the “Warner Bros.”), Great Adventure joined the movement of “A.D.” parks with its opening in 1974.

Imagined by LeRoy as the first phase of a multi-park entertainment destination, the park – strategically located right between the New York and Philadelphia metropolitan areas – was well positioned to serve as a flagship project from the start.

That included its opening lineup. Like any self-respecting park of the era, Great Adventure opened with a ’70s prerequisite – the Arrow-made Runaway Mine Train – as its only opening day coaster. That makes sense. No coaster better exemplifies the rise of steel in the ’70s than Arrow’s ubiquitous, winding family mine trains…

…Except maybe Arrow’s own move into modern inversions beginning with Knott’s Berry Farm’s revolutionary Corkscrew in 1975, launching a line of “Double Loops” and “Corkscrews” that took the country by storm. In 1977, Great Adventure announced that their new ride for ’78 would be the Lightnin’ Loops – a pair of separate, but intertwined winch-launched Arrow coasters that catapulted riders into a single vertical loop.

(By the way, it was just before the debut of Lightnin’ Loops in late 1977 that Great Adventure was purchased by the then-Philadelphia-based Six Flags, making the retitled Six Flags Great Adventure the second acquired park to gain the Six Flags name, and the fifth Six Flags park overall.)

Lightnin’ Loops gave Great America guests their first glimpse into the ongoing innovations made real and rideable by the still-young steel coaster – launching, inverting, and reversing, all in one pair of nimble, dynamic thrill rides.

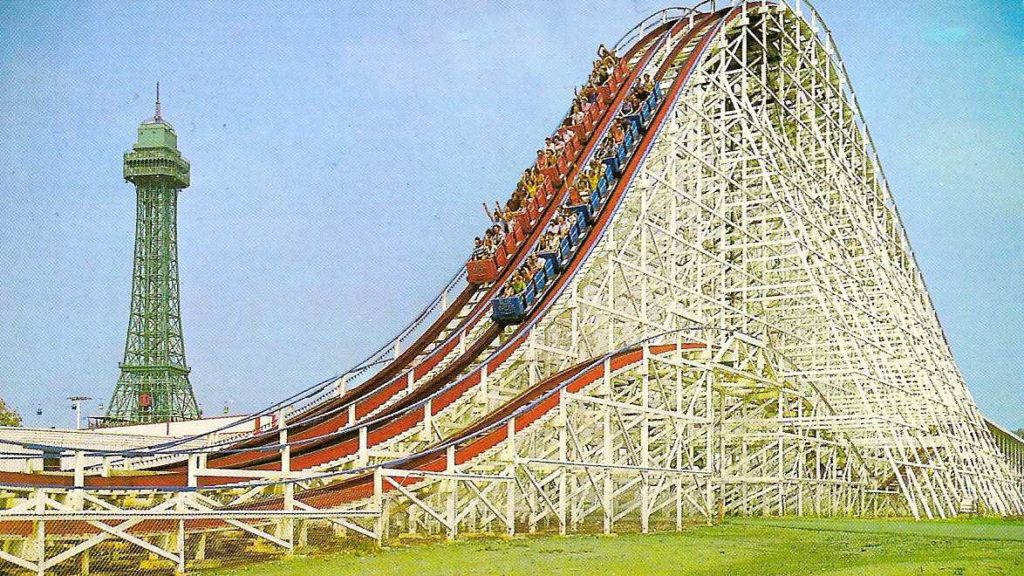

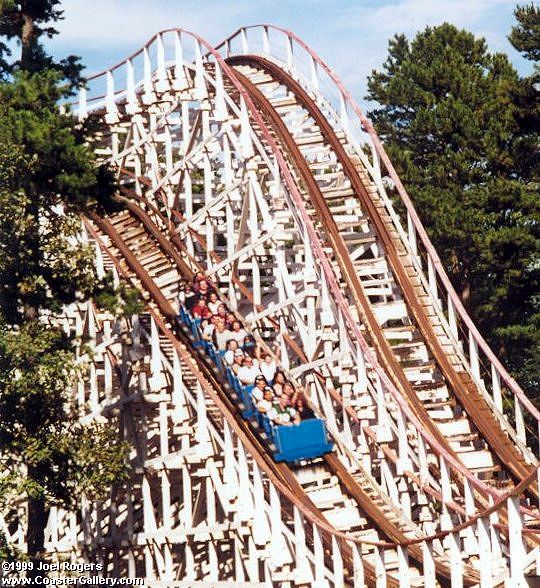

Certainly, the wooden roller coaster couldn’t keep up with that. But there was still much that the medium could offer for a new generation of parks. Like in a real storm, in 1979, Great Adventure followed up Lightnin’ Loops with Rolling Thunder – a gleaming white, racing wooden coaster. Like the Racer before it, Rolling Thunder was a high-capacity, attention-grabbing, marketable, and thrilling experience… that also read as classic; old-fashioned; historic. That’s something that no steel coaster of the era could be. Whether racing or solo, similar entries popped up alongside new parks across the country: Kings Dominion’s Racer 75 in 1975; Carowinds’ Thunder Road, Six Flags Over Mid-America’s Screamin’ Eagle, Valleyfair’s High Roller, and AstroWorld’s Texas Cyclone in 1976; Magic Mountain’s Colossus in 1979; and American Eagle at Chicago’s Great America in 1981.

And indeed, it’s really no wonder that such daintily-painted wooden coasters became de facto ingredients of emerging amusement parks in the ’70s. Equal parts modern and historic, this rumbling, wild, wooden coaster still recalled the heyday of Americana while offering ever-increasing heights, speeds, and drops, keeping pace with evolving steel models.

But in the world of roller coasters, things change quickly… and as the ’70s gave way to the ’80s, audience’s appetites for wooden roller coasters saw the medium evolve in wild ways…