Greater Adventures

When last we left New Jersey’s Six Flags Great Adventure, it was still basking in the glow of 1979’s Rolling Thunder – that classic white woodie gracing the park. Suffice it to say that visiting the park 25 years later, Great Adventure would’ve looked unrecognizable. Sure, there had been the addition of a requisite Arrow multi-looper (1989’s Great American Scream Machine)…

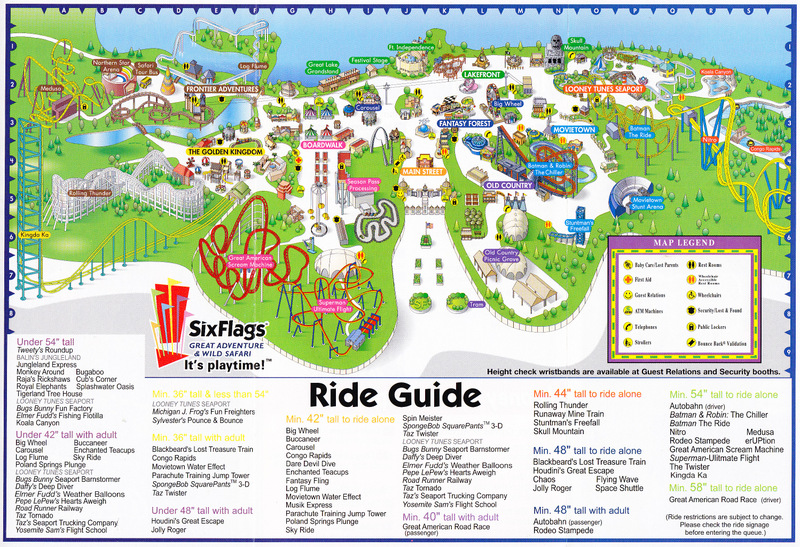

But like the rest of its sisters in the Six Flags chain, Great Adventure’s metamorphosis into a roller coaster Mecca began in earnest in the ’90s with Batman: The Ride (a B&M inverted coaster) in 1993, Viper (a TOGO twister) in 1995, and the cutting-edge, dueling, LIM-launched Batman & Robin: The Chiller in 1998. The Premier coaster was prophetic, as the same year, Six Flags itself was purchased by an upstart operator called Premier Parks (unrelated to the coaster manufacturer) who renamed itself Six Flags Inc.

The new Six Flags Inc. was insatiable, rapidly purchasing parks across the U.S. and Europe and stuffing them with as many thrill rides as they could manage. At Great Adventure, that rapid expansion took the form of three landmark B&M additions: Medusa (the first of the company’s floorless coasters) in 1999, Nitro (an early hypercoaster) in 2001, and Superman: Ultimate Flight (a prototype flying coaster) in 2003. Given Great Adventure’s market – New York and Philadelphia – it makes sense that Six Flags’ new owners would identify it as a new flagship – even among their expanding lineup of coaster parks.

The park’s relentless, coasters-at-all-costs elevation was cemented in 2005 when Great Adventure was chosen over fellow corporate flagships Six Flags Magic Mountain in California and Six Flags Worlds of Adventure in Ohio to receive “the king of roller coasters,” Kingda Ka. Besting the previous record holder – Cedar Point’s Modern Marvel: Top Thrill Dragster – Great Adventure’s 456-foot tall, 128-mph launched Intamin stratacoaster became the tallest and fastest roller coaster in the world… certainly, an icon of the Coaster Wars.

At any other place and time, Kingda Ka would’ve marked the end of a park’s decade of exhaustive expansion. But in the Coaster Wars, slowing down and taking breath was a luxury most amusement parks couldn’t afford. As the first guests were stepping aboard Kingda Ka, the steel structure of the park’s pipeline-style Viper was being removed. Only its station – resembling an abandoned Spanish mission – remained.

On September 28, 2005, fans found out why…

Wood rises

As part of a brand new themed land called Plaza del Carnaval (also absorbing the now-dwarfed Rolling Thunder), Six Flags Great Adventure would become home to El Toro.

“Classic design meets state-of-the-art thrills with our spectacular, new wooden roller coaster,” said Rick McCurley, the park’s vice president and general manager. “As part of our multi-year expansion to a family destination, this massive coaster adventure will anchor a colorful, newly-themed area evoking the lively energy of Spanish-speaking regions of the world.”

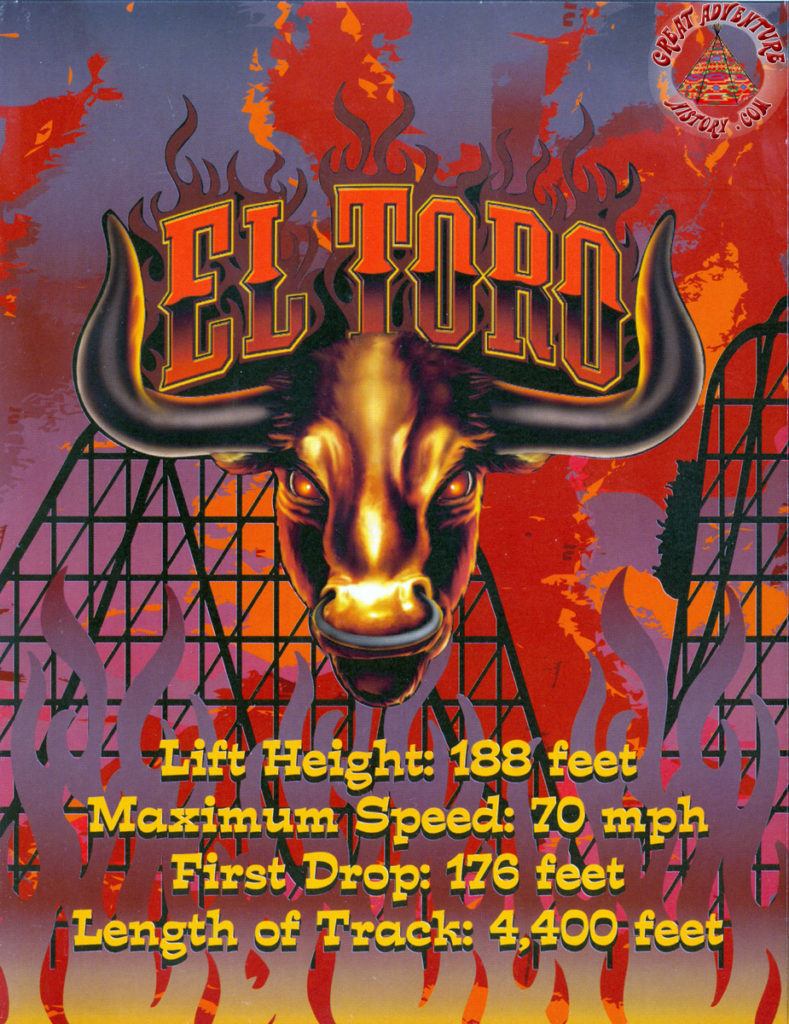

Boasting a 176 foot drop and top speeds of 70 miles per hour, El Toro would become the second tallest and fastest wooden roller coaster on the continent (after Son of Beast), but would use Intamin’s pre-fabricated ride system to achieve an unimaginable 76° first drop (versus Son of Beast’s 55°).

From there, the ride would charge through 4,400 feet of track ‘inspired by the agility and strength of the brave Matadors,” cresting parabolic airtime hills no traditional wooden coaster could tackle. Fusing an out-and-back layout with a twister finale, El Toro would leap over its older sister Rolling Thunder with ease – representing in one single interaction just how far the wooden roller coaster had come in a quarter century.

Vertical construction began on El Toro just after its announcement, in September 2005. Thanks to Intamin’s “plug-n-play” technology, the ride’s 188-foot tall lift hill was topped off before Christmas.

The speedy assembly of pre-fabricated, pre-assembled sections of the ride also provided off-season construction tours with the unusual and distinct experience of seeing seemingly-unsupported sections of the coaster rise independently, gradually growing toward each other and eventually joining in jaw-dropping, pre-planned, perfect precision.

Though Intamin billed the ride’s pre-fabricated nature as a major benefit for the time and money saved in a relatively quick on-site installation process, there’s no question that the model more than made up for the money saved with the highly specialized process. Reportedly, El Toro’s total cost topped out at $28 million – $3 million more than Great Adventure had spent on Kingda Ka the year prior. Was it worth it? Let’s step aboard to find out…

Don’t fight it; ride it

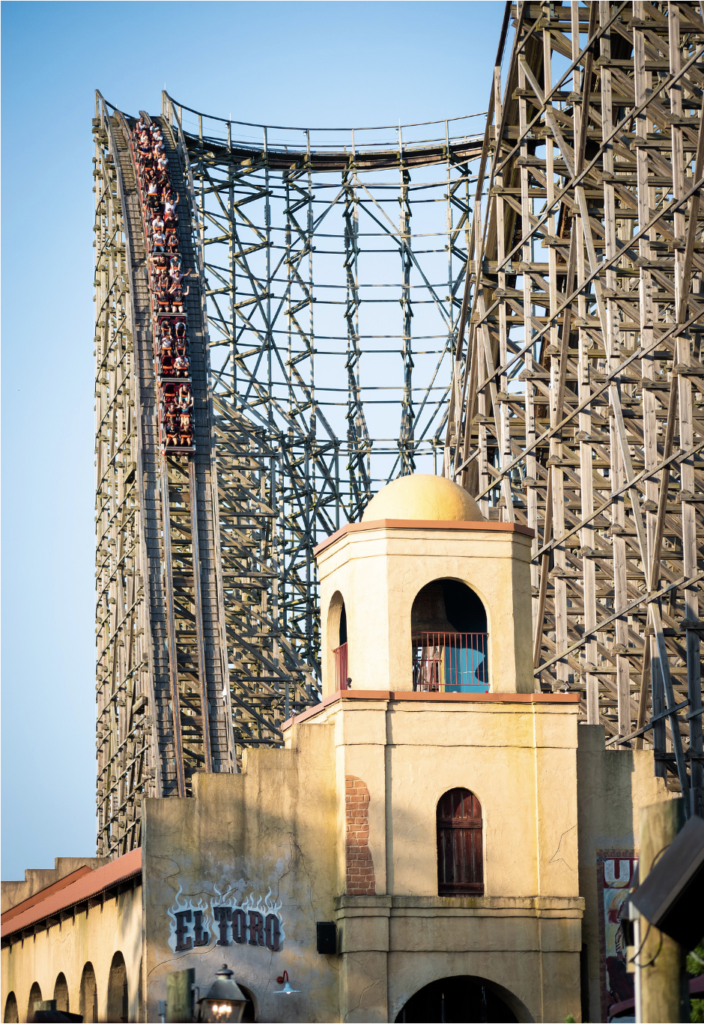

Even from a distance, something about El Toro looks… different. Sure, it’s got all the makings of a wooden roller coaster – the lattice of lumber, the shuffling train stock, the distinctive sound… but El Toro seems to use those same ingredients in a way that looks… just… different.

Its first drop appears to the naked eye to be practically vertical; its parabolic hills are shaped more like a B&M hypercoaster than what you expect of wood. Even its lift hill looks as if it’s steeper than usual, as if someone stretched a typical wooden coaster vertically. And upon close inspection, there’s an unusual level of… maybe… symmetry?

Drawing closer, the supports that scaffold El Toro’s lift and first drop are practically geometric perfection, branching and fanning like fractals. Despite being tall and thin, El Toro somehow looks sturdier; more robust; more sure than you expect of wood.

Of course, all of that is possible because El Toro isn’t quite like other wooden roller coasters. Instead, Intamin’s unique engineering process means that El Toro looks different from other woodies because it is different, and can do things that its sisters cannot. As evidenced by the classic Rolling Thunder that looks like a kiddie ride in its shadow, El Toro is a ride that ignores the so-called limits of its genre and adds an addendum to the rule book. And it starts as soon as the ride does.

Dispatching from the station, the train coasts around the corner, aligning with El Toro’s lift hill. But if you expect a pulse-pounding climb to the apex to the sounds of a rattling chain and the ker-clunking of anti-rollback wedges, think again.

Borrowing from Intamin’s innovation on Cedar Point’s Millennium Force, El Toro ditches the leisurely lift in favor of a high speed cable lift. And unlike Millennium Force (where the elevator cable connects to the catch-car while guests load), El Toro’s lift connects to the train while it’s in motion. Once the first car of the train has passed over it, the cable springs into action, slotting into the catch car and beginning a 13.5 mile-per-hour ascent up the hill. In 16 seconds, it’s there. You might event get a little pop of airtime as the train crests the peak and levels out. After all, unlike a typical coaster, El Toro doesn’t send riders plummeting right away. Instead, it teases us with a view across Great Adventure’s safari park, turning toward Kingda Ka, then aligning with the ride’s out and back layout. Of course, there’s only way to get back: we have to go out.

Gradually gaining in speed, we reach the precipice, the track bending away below and out of sight. And just like that, El Toro plummets. It’s a legendary first drop: 176 feet and reaching 76 miles per hour… but more to the point, it’s blissful. Weightless. Glorious. And while you might expect to have to brace for the inevitable moment when the coaster will reconnect with the track, cratering into the downswing of the hill at full speed, it… doesn’t.

Instead, El Toro snakes through the valley with tremendous power and speed, but without any jackhammering or vibration. It’s… smooth.

Filled with fury, the bull charges ahead, racing up the ride’s second hill – still a staggering 112 feet tall. It barely looses a single shred of speed as it arcs over the ultra-tight hill, leaving riders with the terrifying and enviable experience known only as “ejector air.” Without so much as a breath, it thunders onward over a third hundred-foot-plus hill, the train tactilely pulling up away from the track (thanks for those up-stops, John!). So far, the train’s own airtime-fueled grip seems to be the only loss of speed to friction.

El Toro can’t be tamed. It bolts ahead, relentless. The ride’s fourth hill – and the furthest point of its out-and-back race toward the rest of the park – is still a substantial 82 feet tall. It tosses riders to the ride, rumbling through a descending turnaround, then rising back up to realign with the narrow layout’s footprint. El Toro dives into a series of stretched parabolas, dipping into the ride’s superstructure As it races back into the cradle of the ride’s first drop and the general direction of the station, you might expect the ride to give up, sending the train tearing back into magnetic brakes to shed its speed and send us home.

But nope. El Toro rises a final time (until Rolling Thunder was removed in 2013, leaping over[!] its first drop), then races to ground level. The ride now enters its grand finale – the bull’s last attempt to buck us pesky riders once and for all. A hidden, spur, out-and-back segment clings to the grass, trading airtime for laterals.

The bull banks left, then right, tossing us side to side in a wild ode to wooden twisters of old… (and maybe, a test case in the lead up to Intamin’s next ride, 2007’s Maverick at Cedar Point). It dips and slaloms in a wild last chase, all edged within the layout of Rolling Thunder. But as it makes a final leap into the brakes, the unstoppable speed of El Toro finally evaporates. Using every single joule of energy it gained in its climb a minute earlier, the ride retains just enough momentum to take the final dip back to the station.

You’d be forgiven for being speechless upon returning to that old Spanish mission station. El Toro is fierce and wild; untamed and furious. Yet it’s also sleek and smooth; unafraid to toss riders around, bolting them up and yanking them down hills in ways usually reserved only for its steel cousins. Because while there’s no question that El Toro is a wooden roller coaster, it doesn’t feel like it. It’s legendary. Astounding. Perspective-shifting.

And at least for a moment, it seemed possible that in El Toro, the future of the wooden roller coaster was laid bare; that Intamin’s pre-fabricated wooden coasters might’ve been the solution the industry needed to send wooden coasters past their long-imagined limits at last… That is, until everything changed…