Copymouse

In 1995, Disney signed an unprecedented licensing agreement with competing movie studio Metro Goldwyn Mayer, awarding Disney exclusive, international rights to MGM’s name, brand, logo, and a collection of classic Golden Age films in perpetuity for use in a brand new theme park: The Disney-MGM Studios.

Then-CEO of Universal’s then-parent company MCA Sid Sheinberg publically suggested that Michael Eisner’s greenlighting of a Disney studio tour had been an unethical preemtive strike against the company; that Eisner unfairly knew about Universal’s plans in Orlando because he’d been approached to co-finance the park when he’d been the head of Paramount Pictures.

(After a public inquiry from MCA, Disney released a statement in which the company “categorically denied” the rumor that Eisner had unfairly , or that Disney “stole, borrowed or misappropriated anyone else’s ideas for the [park] – or that Disney will ever do so, or would have to do so.”)

What’s worse, Disney’s unique legal arrangement in Central Florida (wherein the company essentially has governmental oversight of itself) meant that Disney’s fast-tracked, “half-day” park could come online quickly, beating Universal’s from-scratch build.

Even still, the Disney-MGM Studios would be built around only two major attractions: the first would be the elaborate dark ride once envisioned for Epcot (a fellow Lost Legend: The Great Movie Ride), and the second would be – you guessed it – a Backstage Studio Tour through the park’s working studio facilities, backstage areas, and staged “catastrophes.”

Universal’s own bread-and-butter – its iconic tram tour – had been ripped out from underfoot and repurposed by its competitor. A 1989 Washington Post feature by Ellen Farley entitled “WHOSE IDEA WAS IT ANYWAY?“ notes:

Jay Stein, MCA’s chief tour executive, says his company was forced to completely restructure its Florida tour in light of the similarities. The restructuring added “tens of millions to the cost,” Stein says. “It isn’t just the redesigning. It was the addition of new attractions and shows, expanded streets and restaurants, that were not contemplated in 1981. It all relates to the fact that Disney took what we had, and we had to fish or cut bait.” MCA says it is spending $500 million, up from the originally projected $200 million. […]

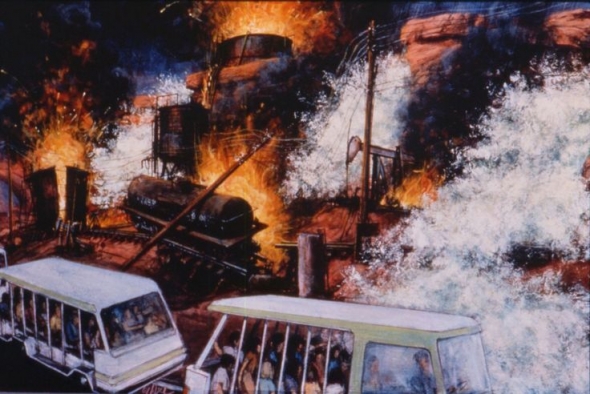

They say the most striking similarities exist between Disney’s “Catastrophe Canyon,” an adventure ride segment on its back-lot tram tour, and parts of MCA’s original plans that included an earthquake ride.

Asked why MCA chose to disclose the old tour plans, given that its focus now is on its new attractions and new tour, Stein says, “I just think that when you work as hard as we did in trying to get this program and studio tour off the ground — and this is a project that I have worked on for 20 years – then you see someone come along and take your ideas and … incorporate them in their project and say that this was their idea, [that] this was conceived by the [Disney] Imagineers, that just makes me angry.”

Here’s where karma kicks in. Disney might’ve beat Universal to the punch, but Eisner had intentionally under-built the Disney-MGM Studios, sure that the multi-hour Backlot Studio Tour would be the park’s real draw.

But as quickly as it opened, the Studios’ concept sunk. Disney and Universal’s dreams of turning Orlando into a “Hollywood East” were quickly dashed and production never really came to Disney’s studio park. The grand tram tour meant to be the park’s star attraction quickly became a ride worthy of its own Declassified Disaster: The Backstage Studio Tour feature; merely a showcase of vacant and repurposed facilities that would never actually be used for filming anything.

And since Disney had stolen the Studio Tour that would’ve been the centerpiece of this own Orlando park, Universal Studios Florida creatives would have to change plans. Brilliantly, Universal adapted. The staged elements and encounters that had been mere blips along Hollywood’s grand Studio Tour were instead separated out and re-imagined as full, standalone E-Ticket attractions of their own.

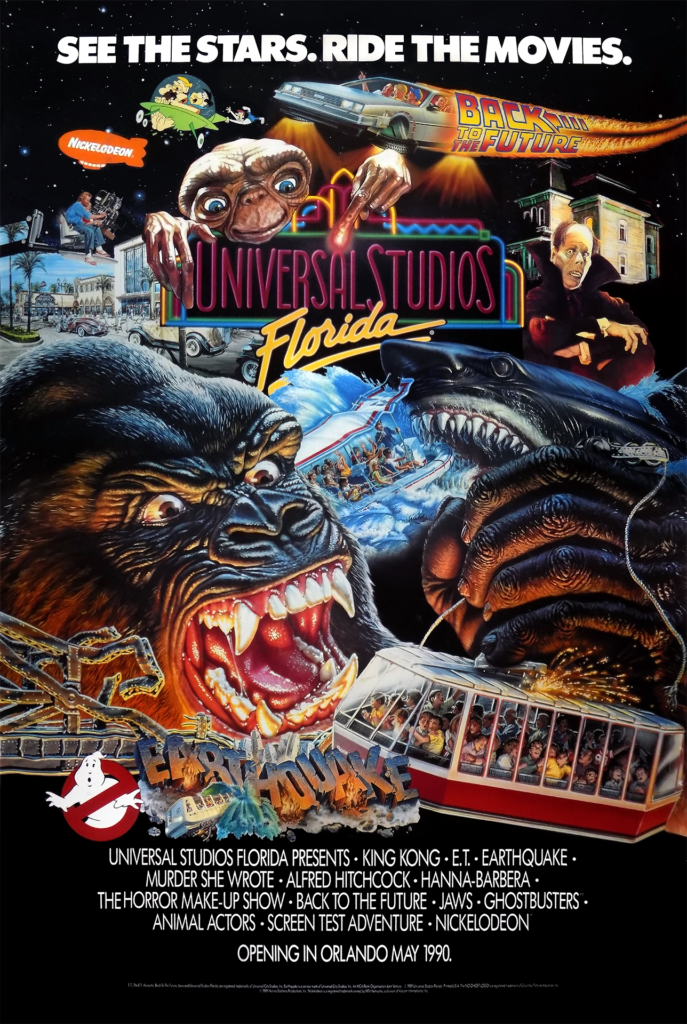

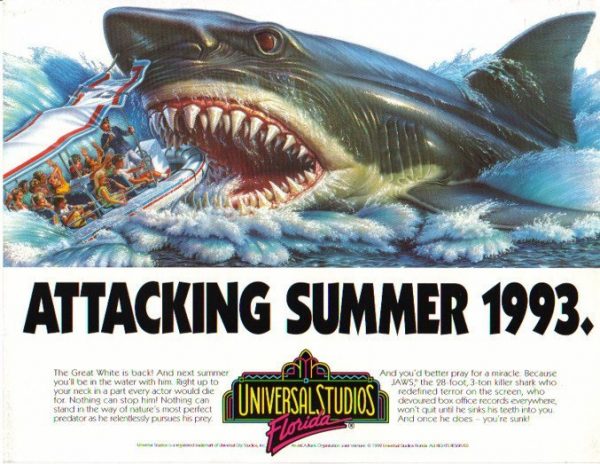

And yes, one of those headlining new rides was JAWS. But it’s probably not the Jaws that you remember…

JAWS: Take 1

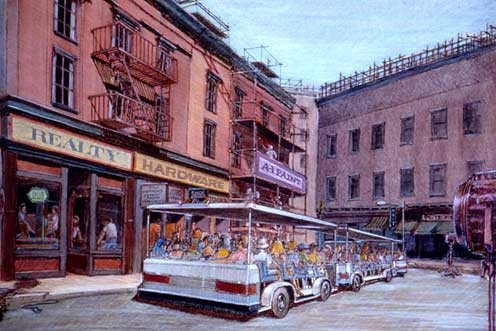

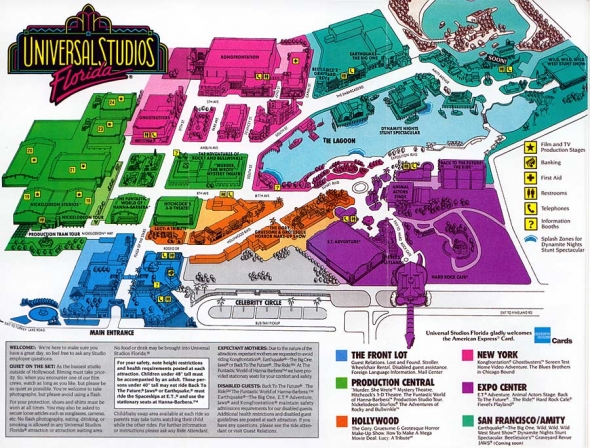

When Universal Studios Florida opened on June 7, 1990, JAWS was one of its must-see attractions alongside Earthquake: The Big One and the Lost Legend: KONGFRONTATION (with all three being extended standalone rides based on Studio Tour scenes). Even if this project was bigger, Universal Planning and Development brought on Ride & Show Engineering Inc. (the designers of the Studio Tour’s Jaws scene) to recreate their magic on a grander scale.

On-board pontoon boats piloted by a live skipper, guests would explore the coves and bays of Amity Island for a number of close encounters with the great white himself. While he was sometimes visible only as a dorsal fin slicing through the surf, the shark was also present a number of times via impressive animatronics.

In one particularly unique scene, the shark would burst from the water, physically bite onto the boat (see the Passholder-exclusive image, above), and drag it backwards, rotating the ship 180-degrees on an underwater turntable.

The explosive finale involved a grenade launcher and a hungry shark, mirroring the finale of the film. The skipper would shoot a grenade into the shark’s mouth just as it charged the boat.

The ship would sway as Jaws seemed to pass beneath, then after a few agonizing seconds of silence, a massive geyser of bloody water would explode from beneath, spraying fleshy chunks into the air. Seriously. (As per the trademark filing above, the “meat” would then sink into a funnel hidden beneath the water’s surface only to be launched skyward again for the next boat… Seriously!)

You can see the original version of JAWS in action in this rare point-of-view video filmed as a training reference for the ride’s skippers:

From the start, JAWS was an ambitious ride with some cutting-edge animatronics and sincerely tense moments; a “Disney quality” attraction in terms of detail, effects, and interaction. The problem is, the ride didn’t work.

Industry experts saw the writing on the walls. Disney Legend Bob Gurr (at the time the vice president of the Sequoia Creative design firm) reported later that he’d taken one look at the plans and passed at making a bid to build. The ambitious ride was determined to rival Disney, and on paper it did. But engineers knew that mixing electricity, hydraulics, animatronics, synchronized audio, boats, and water would require immense expertise and a handful of backup plans.

Allegedly, faulty special effects, frazzled computers, and animatronics that were improperly waterproofed led to almost daily evacuations and extensive breakdowns. The ride limped through its opening summer (a summer marked by sincere hardship given that the park’s other two headliners were disastrously designed, too and the beloved Lost Legend: Back to the Future: The Ride’s opening was delayed a full year), but by August 1990, Jaws had had it.

The ride closed two months after it opened and Universal sued Ride & Show Engineering for improperly designing the ride, citing “poor workmanship.” The then-president of Universal Studios commented on the debacle, saying, “We have suffered tremendously. Ride & Show did not deliver on what they said they could deliver on. In the interim, we had to discover and correct problems at our own expense. I think we have been more than reasonable.” For two years, Universal worked toward re-opening the waterlogged ride, but it was no use.

A New Hope

After years of being closed, Universal started from scratch. They hired some prominent attraction-engineering firms and designers. Intamin Worldwide (best known as a roller coaster and water ride manufacturer) designed and built an entirely new ride track and control system with ITEC Entertainment, who developed software to control the precisely-timed show.

Oceaneering International, a global leader in deep-sea research equipment, constructed seven brand-new fiberglass and steel sharks. Their engineering skills would be tested, given that each time a shark burst from the surf, it would require 500-horsepower of thrust – about equivalent to the force needed to get a Boeing-737 aircraft off the runway – giving the sharks a thurst speed of 20 feet-per-second.

An unimaginable undertaking, the 7-acre, 5,000,000 gallon lagoon was rewired with 2,000 miles of electrical wiring and underwater track by Intamin. Additional tracks (for the sharks to “swim”) each carried 12-ton hydraulic lifts (to make them “jump”, above).

The new engineers and designers determined that two of the ride’s scenes – the “boat biting” scene and the “exploding shark” scene were so impractical, they didn’t even warrant rebuilding. Instead, they’d be replaced by an exploding gas dock and a shark fried by an underwater electrical cable (based on the finale of Jaws 2). They’d also fill in much of the ride’s vast emptiness with new scenery and a dark and imposing boathouse.

When it’s all said and done, the complete rebuild was said to cost an additional $45 million on top of the original version’s $30 million price tag, not to mention causing Jaws to officially and finally debut in its complete form three years after the park. In Spring 1993, Steven Spielberg was on hand with the film’s stars – Roy Scheider and Lorraine Gary – to rededicate and re-open JAWS.

Ready to ride through what guests found on this true classic? Read on…