Making Magic

By the dawn of the 1990s, the stars had aligned. After the opening of Splash Mountain in 1989, an energized Michael Eisner – in the midst of his “Ride the Movies” resurgence of Disney Parks and spurred by the dawn of the Disney Renaissance – was eager to greenlight a show to pack Disneyland’s riverfront restaurants at dinnertime. He was even willing to approve the laborious work and tremendous expense of completely reconfiguring Tom Sawyer Island, the Rivers of America, and New Orleans Square’s waterfront for the right concept.

Sailing ships. Flaming rivers. Giant props. Puppets. Riverboats. A sorcerer’s apprentice. Classical music. Frightening villains. Crackling fireworks. Electronic fanfares. Searing lasers. Dancing fountains. A choreographed cast…

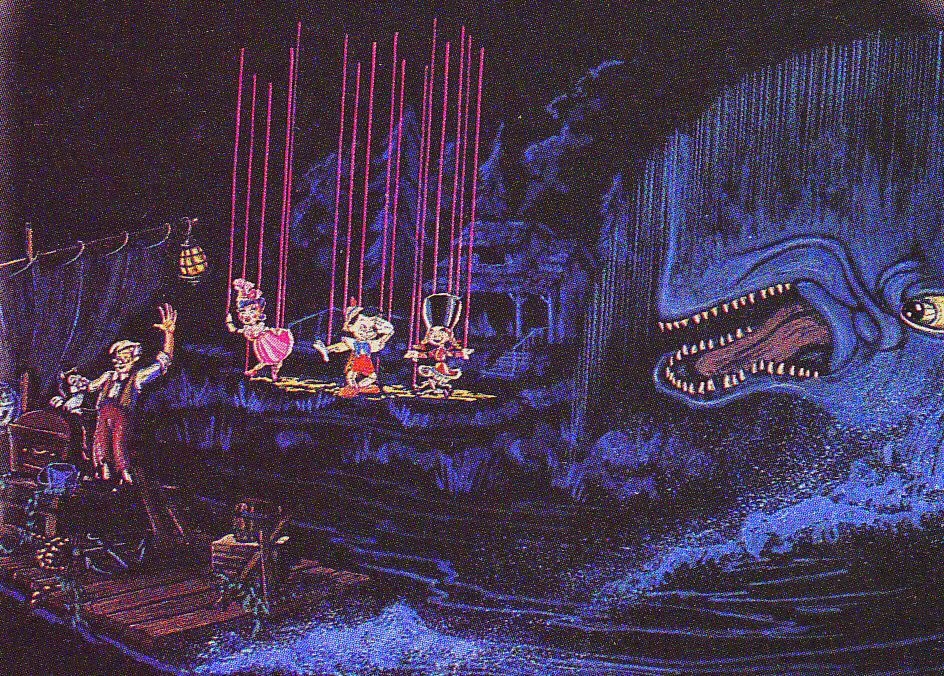

Dreams of phantoms, Fantasia, and Laserphonic fantasies must’ve been dancing in Imagineer Barnette Ricci’s head as she began to envision a show using the spirit of the River Haunt, the scale of the Rollin’ River Revue, and the music and magic of Fantasia. Ricci’s show, however, would go in an entirely new direction: into the worlds of classic Disney stories and the worlds of animated feature films.

To that end, Ricci had unknowingly taken the helm of one of the most ambitious projects in the history of Disney Parks’ entertainment: a show-stopping new entry in the emerging “nighttime spectacular” genre that would require the cooperation of Disneyland Entertainment, Walt Disney Imagineering, and Walt Disney Feature Animation.

To our thinking, there were 3 major breakthroughs that cemented this after-dark extravaganza’s place in the minds and hearts of Disney Parks enthusiasts…

1. The Screens

Like the River Haunt concept that had come before, Ricci’s after-dark extravaganza would utilize a massive cast, enormous props, theatrical lighting, magnificent sound, and Disneyland’s fleet of watercrafts. However, there was one speed bump to overcome: screens. Surely, any show meant to celebrate Disney animation would need to show curated clips from classic films (and if 1989’s The Little Mermaid were any indication, maybe a few nods to Eisner’s own Renaissance-era characters, too).

However, the notion of unfurling massive projection screens had been a headache enough to stop development of a Fantasia showcase eight years earlier, and would be totally impractical if Ricci expected her show to alternate between animated scenes and staged ones. Silver white projection screens raising and lowering wouldn’t just halt the show’s magic and momentum; they’d be a limiting factor in developing the show’s viewing areas that needed to absorb thousands of guests per showing.

It was on a research trip to Paris (perhaps tied to the Euro Disneyland project) that Ricci found her answer. There, reportedly by way of a French cultural celebration, she stumbled upon a technology developed and patented by the French company Aquatique Show that they dubbed a “water screen.” Using a high-pressure fan nozzle, Aquatique’s technology could create a semi-circular fan of mist up to 18 feet high and 60 feet wide, continuous enough to capture rear-projected film footage.

As the Member-exclusive patent imagery above demonstrates, the unique system included a revolutionary “apparatus for projecting water under pressure to form a screen, made up of transparent droplets that are capable of reflecting light rays striking the screen by back-projection from the projector, thus making the screen a receiver of moving or still images.”

Ricci later remembered:

We had already gleaned all this information about mist screens on which we could project light beams and lasers. Then we received a demo reel from a French company. It showed a water screen with film projected on it. What if Disney animation was projected onto those screens? It would be incredible!

By layering the dancing water fountains, special lighting, lasers, pyrotechnics and black light, along with live performers on watercraft and this new way to project animation on water, I was convinced all of these elements combined would create a rather exciting show! […] It took months of searching through Disney film footage to find the right clips for the storyline and to create the film elements so they would look great on the water.

Aquatique’s technology was a win-win-win. Water screens could beautifully showcase the animated footage Ricci needed, act as evanescent “curtains” concealing resets on stage, and add to the must-see technological sights and otherworldly mystique of a new kind of nighttime entertainment.

2. The Setting

With Aquatique’s starring water screen technology and fountains joining the show’s arsenal of surprising special effects, Ricci’s nighttime spectacular was officially in production. But what many expected to be a multi-year build turned out to be a race to the finish line. In late 1990, word came from on high: Ricci’s in-development show would need ready to premier for summer 1992, bridging the gap between 1989’s Splash Mountain and 1993’s Toontown.

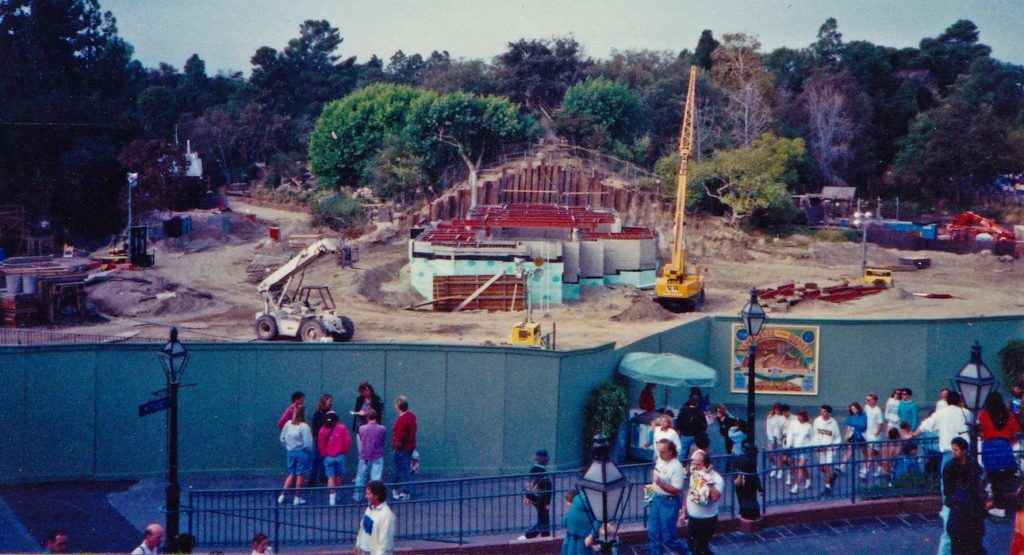

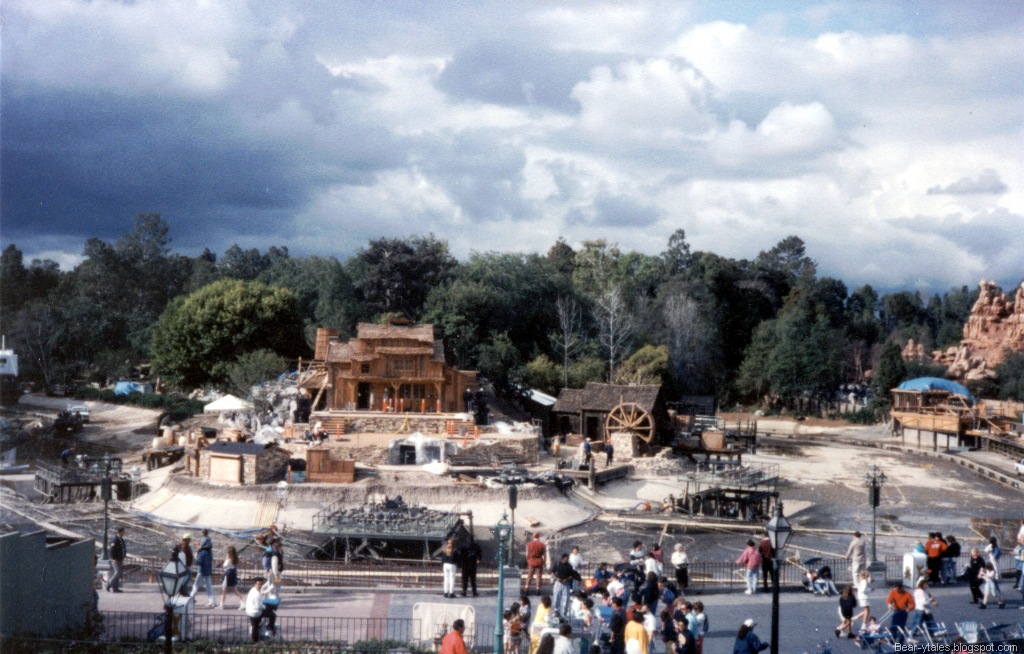

With just over a year before showtime, the Rivers of America were drained and work began on the infrastructure required for the massive show.

First, Tom Sawyer Island – which had been largely untouched since its 1956 opening – was literally reshaped and at last gained its permanent, integrated stage. Guests traversing the island’s dock and new cider mill by day would find no trace of the hidden hydraulic lifts, lighting pits, or the 20-by-20 foot wide, 25-foot deep show pit serving as a dragon’s sleeping quarters beneath it all. Even thematic refuse along the shore – boxes, barrels, and rocks – would completely conceal the show’s projectors, flame-throwers, and other embedded effects. The island’s Fort Wilderness was equipped with changing rooms and support facilities for the show’s cast.

While the waterway was drained and a new backstage marina added, the Rivers of America was reclad in gunite – a sprayed concrete mix of cement and sand, at last permanently replacing the packed clay that had acted as a solution to water loss since 1955. Natural gas lines were run along the bottom of the concrete river. Three fountain pits were constructed, each containing a rising platform of lighted show fountains and a large water screen fan nozzle fountain.

Those fountains were fed through massive intake pipes concealed along the length of New Orleans Square’s waterfront. MeeFog mist effects were also embedded into the refreshed shoreline. Even once the River was refilled in spring 1992, it remained a construction zone.

Speaking of which…

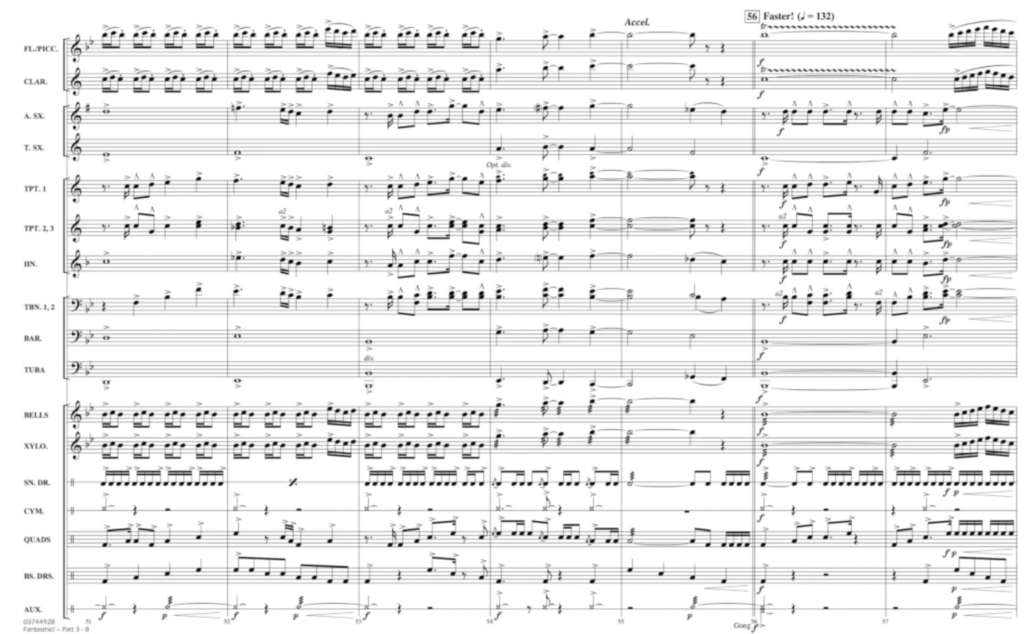

3. The Score

You may not know Bruce Healey by name, but chances are, you’ve hummed his work. After all, as the Principal Music Director / Producer for Disneyland Entertainment, Healey reportedly produced every musical score in every parade, show, and nighttime spectacular at the Disneyland Resort between 1984 and 2017 as well as scoring Shanghai Disneyland the Fantillusion parade in Paris and Tokyo, and work across Walt Disney World.

Yet of all his productions and compositions, Healey told his alma mater, Cal State Fullerton, “‘Fantasmic’ still tops the list.” It’s easy to imagine why. First of all, Ricci’s show required that Healey adapt songs and scores from Fantasia, Pinocchio, The Jungle Book, The Little Mermaid, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Beauty and the Beast, and Peter Pan.

At the same time, Healey needed to compose an original score to contain the show’s multitudes and capture its unique spirit. He reflected on the task:

I like “classical” forms – those forms that contain a logical evolution and repetition of a theme. I also like the concept of the “leitmotif” which identifies a particular musical theme with a specific character in a story. I employed both concepts in that score, and it’s memorable, I believe, because of that.

I also am not ashamed to call myself a melody writer, and an arranger of themes. Some composers look down on the use of a highly memorable melody and prefer to create more abstract music.

There’s a place for both in the multimedia world. Fantasmic! as a multi-media show, was my opportunity to use many of the film scoring, compositional, arranging and orchestration techniques that I studied since before college, all in one project.

Test and Adjust

In late 1991 – before the Rivers had even been refilled – billboards and advertisements across Southern California announced a new show coming to Disneyland…

… The Imagination river spectacular was on its way. Early promotional material beautifully described the experienced by suggesting, “It starts with a single note… then erupts into a symphony of magical music… a pageant of whirling, twisting waters, and a cosmic explosion of laser lights.” Meanwhile, a rare pre-opening concept video showed early test footage of the water screens and staging, promising “the scope, the combination of special effects, the energy, and the emotion will amaze you; you have never seen anything like the Imagination.”

Behind the scenes, though, coordinating a nighttime spectacular with technology of the early ’90s was no small feat. According to Ricci:

“We spent three months of ‘all-nighters’ out there on the river, programming all the effects and meticulously finessing the timing based on the time code of the film. Every burst of water, pyrotechnic, laser and live element had to be exactly timed and rehearsed to be in sync with what happened on the screen and with the fantastic musical score. […] But everyone felt it needed a stronger title.“

Disney Legend Jack Lindquist – Disneyland’s President at the time recalled the process of titling the show just two months ahead of its debut…

“We got a big dictionary down from Michael [Eisner]’s bookshelf and started going through it page by page. We both kept throwing out names and rejecting them. Finally we had reached the Ps and Michael threw out ‘phantasmagoria’. It immediately intrigued us both. The meaning related. It had the right feel. We liked it. I took it to Bob McTyre, Mike Davis and Henry Carroselli, the advertising art director, and a week later took the first logo concept for Fantasmic! back to Michael…and the rest is showbiz history.”

With a final budget allegedly topping $30 million, FANTASMIC! was set to be of a scope far exceeding any Disney Parks show before, elevated to an echelon of scale, ambition, and expense typically reserved only for E-Ticket rides. (By the way, we do controversially include Fantasmic! as a headliner at Disneyland Park in our per-park count of E-Tickets…)

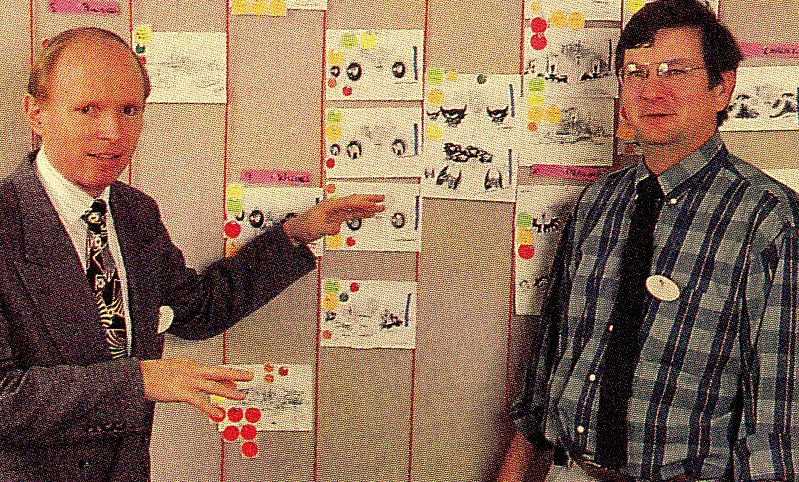

With the show’s Screens, Scene, and Healey’s carefully-curated Score delivered (and lyrics for it written by Barnette Ricci herself), everything was coming together. As the Member-exclusive insider feature from an internal February 1992 Disneyland Line (below) assured, the brand new nighttime spectacular was due to arrive at Disneyland by mid-spring.

What could go wrong?

The Night Ignites

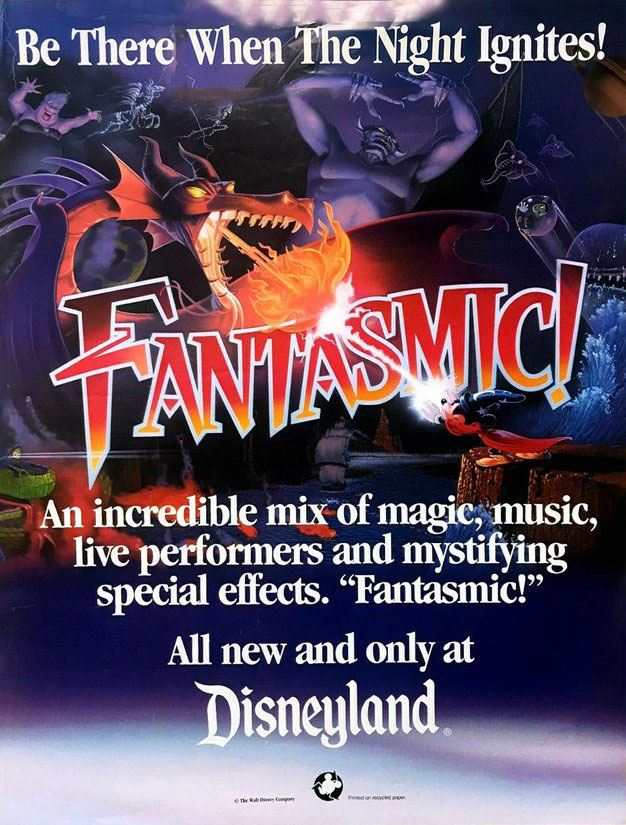

With dozens of fountains, hundreds of pyrotechnics, its starring water screens, its epic score, and nearly a hundred total Cast Member on-and-off stage, Fantasmic! would stand among the other Imagineering feats of the “Ride the Movies” era. As evidenced by the show’s must-see pre-opening commercial, Fantasmic! was advertised for what it was: a headlining new addition to Disneyland. Who wouldn’t want to “Be There When The Night Ignites“?

The show’s press premiere was set to take place on Wednesday, April 29, 1992 with public soft openings to follow.

However, that very afternoon and just 60 miles northwest in Simi Valley, California, a jury acquitted four Los Angeles police officers tried for assault and excessive force in their arrest of a Black man named Rodney King. In an era before video recording was widely accessible (and routinely captured the violent treatment of Black people at the hands of police), the abhorrent assault of King was captured by a bystander on his camcorder and subsequently spread via television. As a result, the officers’ acquittal became international news earning global condemnation, even from then-President George Bush.

The tipping point in the decades-long accumulation of “ethnic tensions” in the city, the abrupt end of the LAPD trial was the final spark that lit the Los Angeles Riots. During the weeklong event, the 1992 Los Angeles Riots saw 12,000 arrests, 2,500 injuries, 63 deaths, and reportedly over $1 billion in property damage. Over 1,100 buildings were destroyed by fire, with some estimates suggesting the Los Angeles Fire Department fielded an average of one call per minute during the riots’ peak.

Hours before its planned premier, Fantasmic! was postponed, and Disney’s call to “Be There When the Night Ignites” was quickly scrubbed from promotional material and billboards – a change that didn’t go unnoticed by The Los Angeles Times, who mentioned Fantasmic‘s marketing push in its 1992 “Bad Timing Awards.”

Ultimately, Fantasmic made its official debut two weeks after scheduled, on May 13, 1992.

Ready to step into Mickey’s imagination? As our look behind-the-imaginations continues, we’ll get a glimpse of Fantasmic, see the concept’s spread to Disney Parks around the globe, and watch its evolution in Disneyland.