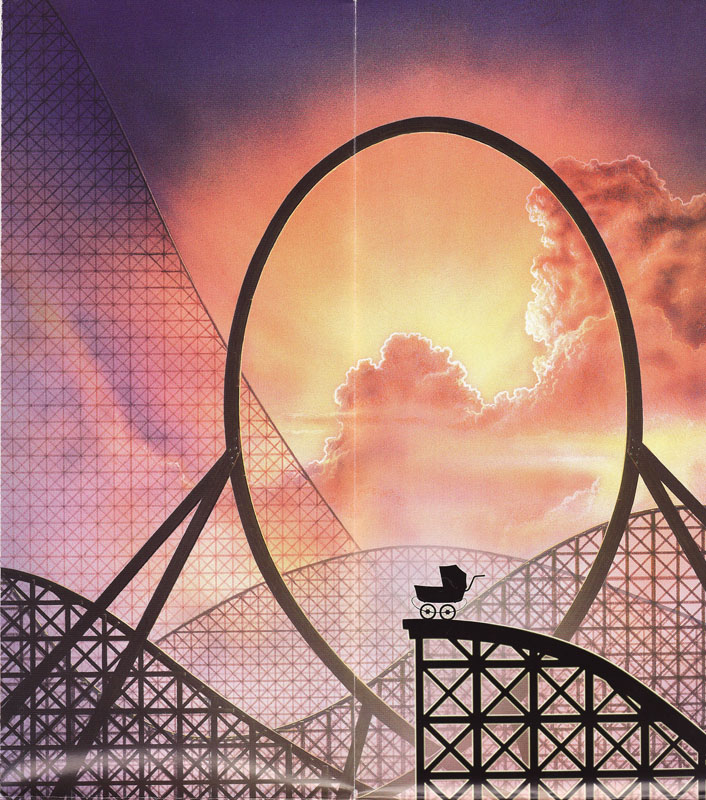

To truly understand Son of Beast, it’s important to understand the way that traditional wooden roller coasters are built. The structures are cut on-site out and secured with bolts and plates to form the intricate support systems. Then for the track itself, layers of laminated wood are stacked, and flattened steel strips serve as the “running rails” for trains’ top wheels (otherwise, the wheels’ friction would destroy the wood). The inherent imperfections in the supports and track are what give wooden roller coasters the bumpy, rough feeling that so differentiates them from the precise and smooth steel coasters.

Son of Beast, like most wooden roller coasters rides built before 2000, was a classic wooden roller coaster with all the imperfections that come along with it.

Today, a glance at the lineup of the world’s tallest wooden roller coasters is telling. Almost all of them were built post-2000, and almost all of them are built by one of two ride manufacturers: Intamin or Rocky Mountain Construction. Those companies have found a sweet spot with two very different wooden roller coaster models.

In 2001 – just one year after Son of Beast’s opening – Swiss manufacturers Intamin unveiled the first of their “plug and play” wooden roller coasters. Unlike all wooden roller coasters that had come before, Intamin’s next generation coasters weren’t cut and assembled on-site, but prefabricated with laser-cut, mathematical precision. Those pre-made, pre-labeled parts are shipped to parks for assembly like LEGO blocks. By eliminating the imperfections inherent in the manufacturing process, these coasters – like Six Flags Great Adventure’s El Toro – are as wood as Son of Beast, but feel more like ultra-smooth, airtime-packed steel coasters. As a result, they’re capable of great height, speed, airtime, and agility.

Rocky Mountain Construction, a newcomer, is increasingly renowned for converting old and often painful wooden roller coasters back into headlining attractions. Most of RMC’s installations are “IBox” track configurations, completely removing old wooden tracks and replacing them with steel. This strategy has yielded some of the most spectacular coasters on Earth, like Cedar Point’s Steel Vengeance (a steel RMC retrofit of Mean Streak), Kings Dominion’s Twisted Twimbers (formerly the Hurler), Busch Gardens Tampa’s Iron Gwazi, and a handful of retrofits of Six Flags rides. To be clear, the vote is unanimous: these are steel coasters.

However, RMC also offers “Topper Track” (above) as an option for both new builds and retrofits of existing wooden coasters. Essentially, “Topper Track” replaces the steel running rails (that all wooden coasters have) with increasingly larger and thicker layers. While debate initially raged, today Topper Track coasters are generally agreed upon to still count as wooden, even if the track system allows for acrobatic moves and elements previous exclusive to steel coasters and Son of Beast: inversions.

The point is, fans can’t help but wonder – what if Paramount had just waited a year or two? Would they have opted for an Intamin prefabricated coaster, or an inverting RMC? Would Son of Beast have been a top-rated next-generation favorite rather than an ultra-rough, ultra-intense, violent, and shocking rise pushing traditional wooden coasters too far?

In 2013, Outlaw Run opened at Silver Dollar City in Missouri. By nature of using RMC’s Topper Track, the coaster counted as wooden… but that didn’t stop it from offering three inversions – a 153-degree overbanked turn and a double barrel roll. That would spell the end for Son of Beast’s famous single wooden inversion… if it weren’t already a pile of firewood by then…

The accident

On June 30, 2006, Cedar Fair – owners of Cedar Point and, by that time, Geauga Lake – announced their purchase of the Paramount Parks for $1.24 billion, immediately inheriting their five North American theme parks including Paramount’s Kings Island.

Nine days later, on July 9, 2006, a structural failure in the “Rose Bowl” double helix of Son of Beast created a bump in the track, causing a train full of riders to jolt. Details have always been scarce, but many fans speculate that a timber in the ride’s structure cracked, sending a jolt down the track that upset a train barreling along the course. One way or another, all twenty-seven riders were evacuated and rushed to the hospital. Seventeen were released within five hours, and two were admitted.

In an ensuing lawsuit investigation by the Ohio Department of Agriculture (the state body responsible for overseeing safe operation of the state’s amusement park rides), investigators argued that the park’s operators were aware of structural defects in the Son of Beast coaster that “put passengers at risk.” They insisted that Paramount Parks Inc. had fired the Roller Coaster Company of Ohio and set out to fix the ride itself using a “Band-Aid” approach, simply adding structural supports wherever they thought the ride needed extra timber without taking into account the loads placed on the ride or even using a computer model to determine where additional support was possible. Instead, investigators argued, they decided to “wait and see what happened… They never really stopped and said ‘we’ve got a problem with this ride as a whole.’”

Barely a week into their ownership of the park, Cedar Fair announced that Son of Beast was down for the count and that the ride would not reopen for the rest of the 2006 season.

The opening of the 2007 came and went, too. The ride was standing but not operating in April, May, and June. Finally on July 4, 2007, Son of Beast was back. But something was different. The original trains designed by Premier Rides were gone, replaced by new, lighter trains by ride manufacturer Gerstlauer. The hope, it would seem, is that the lighter trains would produce less stress on the wooden structure and reduce the violent jackhammering of riders through the Rose Bowl, to boot.

However, the use of the lighter trains required one substantial edit to the ride. When it reopened in 2007, the loop was no more. It’s important to note that the loop had not been involved whatsoever in the accident from 2006. Instead, the lighter trains installed to lessen the structural stress on the ride simply couldn’t navigate the loop effectively, meaning that the loop had to go. Park spokesperson Don Helbig said in 2009, “The removal of loop was a decision the park made so we could use different trains. The trains the ride now uses are lighter and more comfortable than the original trains.”

While fans will forever debate how important the loop really was to the ride (in terms of popularity, pacing, marketing, etc.) the removal seemed to shift guest attitudes nearly as much as news of the accident had. Still, Son of Beast raced on violently without its signature loop. Until…

The end

On June 16, 2009 – less than three years after its allged accident, and just two years after re-opening without a loop – a woman contacted Kings Island, claiming to have suffered an aneurysm (a burst blood vessel in the brain) due to a ride on Son of Beast two weeks earlier.

The park’s spokesperson, Don Helbig, noted that there were no other reports of injuries on Son of Beast that year and that there was no record of the woman seeking medical attention at Kings Island, but noted that the ride would shut down (again) as a precaution during an investigation by the state of Ohio.

The Ohio Department of Agriculture returned to inspect the ride yet again, but this time they could only note that no “irregularities” were found with the ride. The state gave Cedar Fair the go-ahead to re-open Son of Beast, but the ride didn’t re-open.

For the rest of that year, Son of Beast was standing, but not operating – a massive, towering, iconic structure that literally cast its shadow across the park. As you might expect, rumors ran rampant about the trains that had flown off the track during testing (never happened), all the people who had died on the ride (none had, though at least one post-ride death was officially determined to be thanks to a pre-existing condition) and that it would be re-opening soon (it wouldn’t).

Would Intamin or RMC swoop in and save the say, converting Son of Beast into a smooth, sleek, and cuttting-edge icon? Rumors ran rampant. But no movement took place on the ride for the rest of 2009.

Or in 2010.

Or in 2011.

All the while, Kings Island noted diplomatically that they simply hadn’t decided the ride’s fate yet. They noted that they’d explored a few options (probably including a renovation, but who could say?) and just hadn’t decided their course. And think about it – in the real world, removing a behemoth ride like Son of Beast might have a price tag comparable to repairing it. Or, comparable enough to make them competing options.

But by 2012, they figured it out.

That spring, the ride came crumbling down. Literally. Like a tower of toothpicks, Son of Beast was demolished as seen in the must-see video here:

Resting in pieces

Say what you will about Son of Beast; it was one hell of a ride. Even with today’s smooth-as-glass wooden roller coasters, no one else has dared to cross the 200-foot barrier again. Even if Son of Beast didn’t become a classic, it certainly changed the face of the theme park world and will always be remembered for what it was and what it dared to do.

In 2014, the massive plot of land Son of Beast occupied was at least partially put to use with a deserving follow-up: Banshee, the world’s longest inverted roller coaster. Banshee soars through the uneven terrain that once housed the massive Rose Bowl, even zooming past Son of Beast’s Outpost 5 station (which remains standing, used as a haunted house during the Halloween season).

Fitting the folklore of the Irish spirit it’s named for, the queue line for Banshee weaves through a foggy Moorish cemetery filled with cracked and aged tombstones. In a clever nod to the former resident, the most prominent of the gravestones is a ten-foot tall stone column adorned with a bronze plaque of Son of Beast’s logo. All day and night, an eternal flame burns in memorial to the lost coaster.

It must sting that Kings Island spent $20 million to build the ride and allegedly a further $10 – $20 million to fix it. That’s to say nothing of the lawsuits and settlements the park has dealt with after the ride’s various mechanical failings, the legal battle Paramount Parks endured with RCCA and its affiliates, and the ride’s multi-million-dollar demolition. If you’re counting, that’s probably well over $50 million for a ride that lasted less than a decade.

Interestingly, Son of Beast wasn’t Kings Island’s only high-profile failure during the 2000s…. Born of the same cinematic mindset – and with very, very different issues – TOMB RAIDER; The Ride was a technological and design masterwork, in Ohio, that would feel right at home at Universal Orlando today! Doomed for an entirely different reason, Tomb Raider cost $20 million itself and closed just as quickly – the subject of the must-read Lost Legend: TOMB RAIDER: The Ride.

For people who grew up at Paramount’s Kings Island with headlining rides like Tomb Raider: The Ride, Son of Beast, Scooby-Doo and the Haunted Castle, the Italian Job: Stunt Track, Crocodile Dundee’s Boomerang Bay water park, and Nickelodeon Universe, the park they visit today must feel very, very different. Things have changed a lot, and in a very short amount of time. Maybe that’s why people are still so emotionally impacted by the stories of those lost rides that make the Kings Island of just a decade ago feel so far away.

Many of the people who describe Son of Beast as overly rough and uncomfortable are the same people who are heartbroken to see it closed. Its story is unique and unforgettable, and regardless of what you thought of the ride, its life and death are nothing short of fascinating. For those who got the chance to experience it, we’d love to hear your thoughts and memories in the comments below. For everyone else, just imagine the bravado it takes to green light a ride like Son of Beast.

No matter what you thought of the most controversial roller coaster to ever exist, we can all agree on one thing: the sequel is never better than the original. Just ask The Beast, still zooming through the forests of Ohio – and still the longest wooden roller coaster in the world – forty years later.

Thank you so much for reading. Now, it’s your turn to join the story. If you enjoy spending time falling down the “rabbit hole” of Park Lore’s in-depth, ad-free, member-supported stories, consider becoming a Member for as little as $2 / month.

Members can unlock rare concept art in every tale, reveal attraction audio streams in select stories, gain access to over a hundred exclusive articles in our quick-read Extra Features and in-depth Special Features collections, gain exclusive podcast extras, and receive an annual member card and merch in the mail! (Plus, y’know, supporting research-based, ad-free, clickbait-free, in-depth theme park writing!)