How the West was won

Though any hopes of Marc Davis’ Western River Expedition at Magic Kingdom was dashed, Tony Baxter – still fresh out of college – figured that he might as well excise the desert-set coaster he’d developed as part of the project into a pitch all its own.

The result? Big Thunder Mountain Railroad. It was perfect. Not only could this runaway mine train add thrills to Disney Parks for relatively low cost, but it would also give Frontierland a new lease on life. (After all, though the Old West had been a huge part of the American zeitgeist in Walt’s time, by the ’70s, the era of The Lone Ranger was well over, leaving the dusty, tired Frontierland and its Lost Legend: Mine Train Through Nature’s Wonderland as antiques.) But even if Big Thunder would be an E-Ticket in its own right, Baxter didn’t plan for it to be alone…

The Big Thunder Mountain designed for Disneyland (above) intentionally looks quite different from the others across the world. While the mountains in Florida, Tokyo, and Paris are modeled after the angular, geometric forms of Arizona’ Monument Valley, Anaheim’s ride would intentionally be more delicate, borrowing the rounded, balanced, almost-fantasy hoodoos of Utah’s Bryce Canyon. That fantasy touch would not only be a better fit for the smaller and more charming Disneyland; it would turn Big Thunder Mountain into a crossroads; a ride shared between Frontierland, Fantasyland, and… something new.

Discovery Bay

If Tony Baxter had had his way, Big Thunder Mountain would merely be one piece of an entirely new land constructed on the north shore of Disneyland’s Rivers of America. Using Big Thunder Mountain as a jumping off point, Discovery Bay would answer the question, “What happened to all those miners who struck it rich?” Did they settle down in the sleepy mining town of Rainbow Ridge? Of course not! They continued West, bringing their fortune and glory to a turn-of-the-century San Fransisco; a sci-fi, steampunk trader’s port where explorers, adventurers, inventors, and eccentrics would comingle.

Among its wharfs, docks, lagoons, hangars, and lighthouses, Discovery Bay would present a retro-future; a vision of tomorrow as imagined from the past, rooted in literary works by Jules Verne and his fantastical contemporaries. You’d even find Captain Nemo’s Nautilus docked in the Rivers of America! A land of zephyrs and merchants; hot air balloons and submarines, the iconic Discovery Bay might’ve changed Disneyland forever.

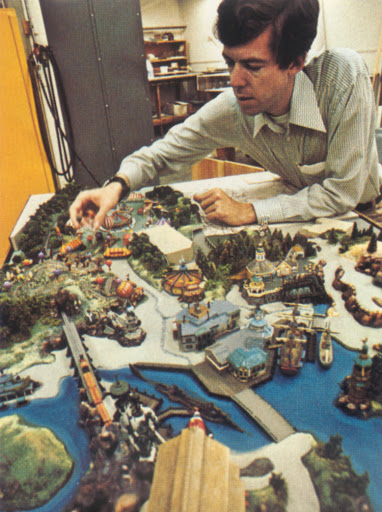

We dove into the full, unabridged story of this never-built land in its own Possibilityland: Discovery Bay feature – a total must-read for Imagineering fans. But of course, despite its official announcement (and amodel on display in the Main Street Opera House, noting its 1976 opening), Discovery Bay didn’t happen. Only Big Thunder Mountain made it off the drawing board, meaning Baxter’s push for a steampunk-stylized retro-future was paused…

International expansion

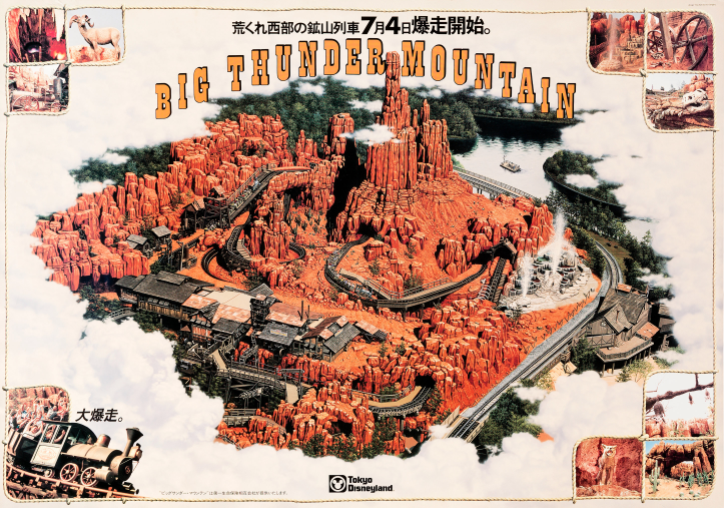

Though Discovery Bay was dead in the water, Big Thunder Mountain became a classic. The ride was a follow-up to Space Mountain, opening at Disneyland in 1979; Magic Kingdom in 1980; then Tokyo Disneyland in 1987!

It’s the latter that’s so interesting… Tokyo Disneyland was Disney’s first ever embassy outside of the United States. And while Imagineers were ready to and willing to work with the Japanese to tune the park to their culture, it wasn’t needed. In fact, the Oriental Land Company (operators and owners of the resort – Disney merely licenses its properties) insisted that they wanted the best of Magic Kingdom and Disneyland, with all the Western, American influences in fact. And unsurprisingly, they were right.

Who cares that the Japanese didn’t have any cultural connection to the Space Age? Tomorrowland was recreated nearly exactly as it looked at Magic Kingdom (except for this being the first Disney Park with Space Mountain built in at opening, earning a prominent position at the end of the land’s entry corridor). Even though there was no “Old West” in Japan, they wanted Frontierland, including Big Thunder Mountain.

With their first foray into international expansion a stunning success, Disney executives set their sights on their next destination: Europe.

La Résistance

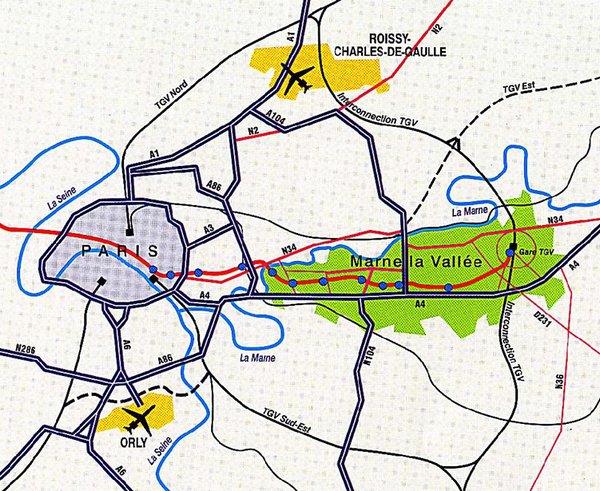

From an initial pool of 1200 potential sites, by 1985 Disney’s executives had narrowed their search to four European possibilities – two in Spain, and two in France.

While the Spanish sites located on the Mediterranean offered tropical climates closely aligned to Orlando and Anaheim, France offered a more competitive financing deal. Voila! Euro Disney would open in the rural village of Marne-la-Vallée just outside of Paris. And given that the 5,000-acre site was no more than a two-hour flight away from over 300 million people, it seemed that the choice was the right one.

But one thing Disney learned right from the start: France is not Japan.

Prominent French intellectuals and writers at once denigrated Disney’s planned resort, with the unfortunate label of a “cultural Chernobyl” becoming a common refrain. Critics called the plans a radical move of cultural imperialism – an American invasion meant to force the unhealthy consumerism of the U.S on France. One reporter for a conservative French daily paper wrote, “I wish with all my heart that the rebels would set fire to Disneyland.”

French labor unions attacked the company over an appearance code limiting makeup, facial hair, tattoos, and jewelry, seemingly imported from American parks with no consideration of French culture or the fact that such restrictions are illegal under French law unless it could be demonstrated that the restrictions were requisite to the job responsibilities and do not exceed what’s necessary. (Instead of relenting, Disney countered that the restrictions were necessary, as employees not adhering would undermine the company’s identity and thus the park’s success.)

Like the Eiffel Tower a century before, the French were determined to oppose the “garish” Disney resort at all costs, blockading its construction and protesting its development. It seemed that nothing Disney could do would quell the anger and hatred that the French felt toward what would surely be an American blight in the French countryside.

But Disney had a coup: Tony Baxter. Chosen as the creative director of the French park, Baxter would take his experiences with 20,000 Leagues, Big Thunder Mountain, and Discovery Bay to help guide his team in crafting a very new kind of Disneyland… one born of rich, romantic, and literary European stories. It was time to rewrite Disney history and shoot for the moon…