Rewriting

One thing was certain to Disney executives and Imagineers: the copy-paste job that had turned Tokyo Disneyland into a hit wouldn’t work in Paris. A Disneyland in Paris was destined to court controversy, period. But no expense could be spared on the park that offered to define Michael Eisner’s legacy, so Imagineering executives pulled out their ace.

By the late 1980s, Tony Baxter’s portfolio had expanded. Baxter topped the credits for Big Thunder Mountain, Discovery Bay, Epcot’s Lost Legend: Journey into Imagination, Disneyland’s New Fantasyland, Star Tours, and Splash Mountain. (He’d go on to lead the design of what may be his magnum opus, Disneyland’s Modern Marvel: Indiana Jones Adventure: Temple of the Forbidden Eye in 1995.)

Disneyland Paris would be his biggest credit yet, even if it was no easy task. After all, Disneyland was Americana incarnate – a gleaming icon of U.S. pop culture, born of fantasies of the Old West, the Space Age, and nostalgic Main Street.; it was, in Walt’s own legendary words, “dedicated to the ideals, the dreams, and the hard facts that have created America.” Now, Baxter and his sensational team of designers needed to inject just enough European romance to make a signature piece of Americana feel unobtrusive in a culture hostile towards its very existence.

What his Imagineering team created is, in the opinion of most, the most beautiful Disney Park on Earth. Disneyland Paris is a wonder. To its credit, it’s often described as the perfect combination of Magic Kingdom’s size and grandeur while somehow retaining the intimacy and coziness of Disneyland in California. Larger than life, yet packed with incredible detail, each of its themed lands is contained within its own berm, totally immersive and entirely self-contained.

Famously, each of Disneyland Paris’ five lands was doled out to an executive producer Imagineer who’d creatively direct the land’s design, tabula rasa. Given that free reign, Baxter’s team designed incredible themed lands that are more cousins than siblings with their American counterparts; fully built out, layered in authenticity, drenched in romanticism, and in many cases, practically reimagined from the ground up.

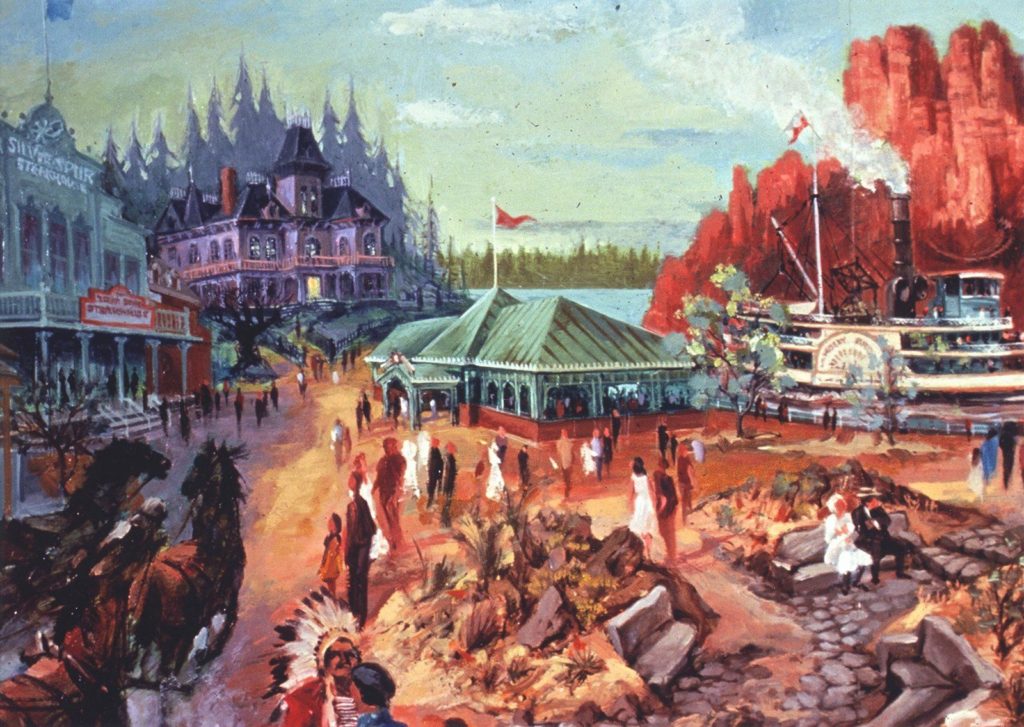

Consider Paris’ Frontierland. Given that Baxter himself had created Big Thunder Mountain, it’s no surprise that it was envisioned as the centerpiece of Paris’ Frontierland (and it is, taking the place of Tom Sawyer Island as the literal center of the land).

With Imagineer Jeff Burke at the helm, Big Thunder Mountain was reimagined as the land’s narrative anchor, too. Burke and his team layered the land with a rich, romantic, and gothic backstory that permeates every ride, attraction, and restaurant in the decked-out land. The most famous example is among the park’s most talked-about, “Bucket List” rides: the Modern Marvel: Phantom Manor, which fuses the Haunted Mansion’s tradition with the tale of the Old West town of Thunder Mesa and the lore of Big Thunder Mountain reigning over it…

In other words, the designers behind Disneyland Paris would need to do

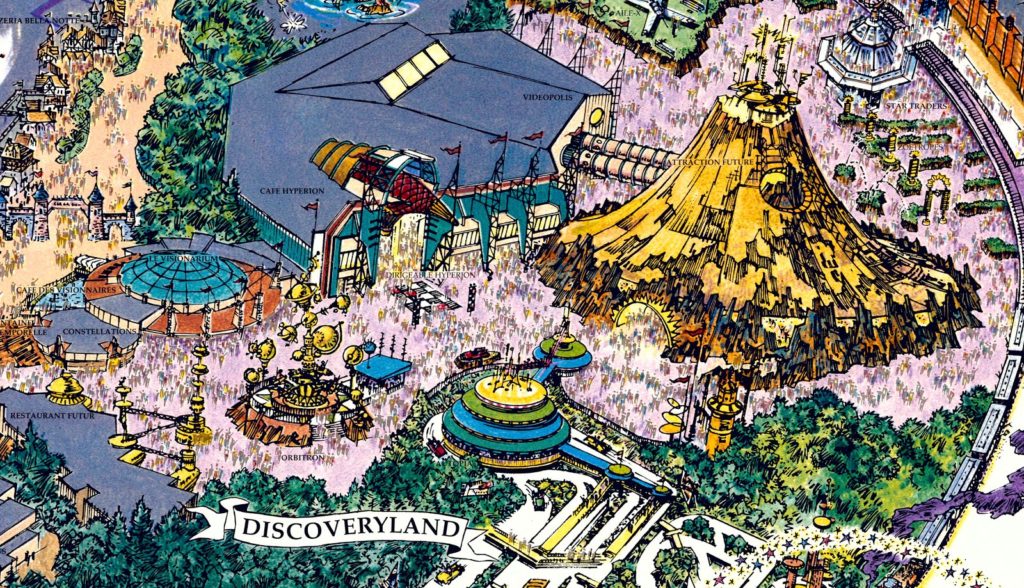

Discoveryland

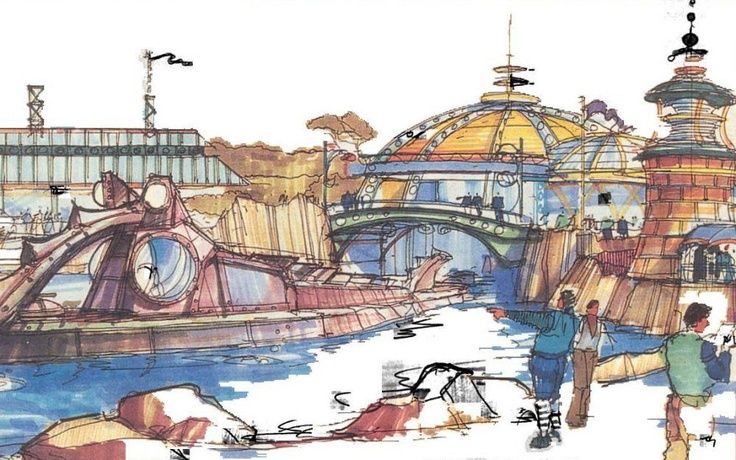

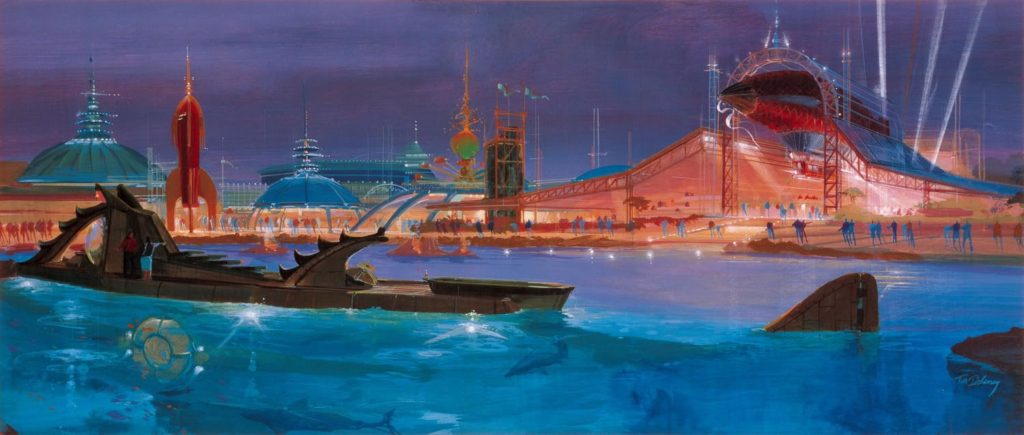

Discoveryland would do away with the tried-and-true signs of Tomorrowland entirely. In its place would arise a golden seaport infused not with science, but with fantasy; an earthy, 19th century land of golden astrolabes, volcanic geysers, bubbling lagoons, forested hillsides, and the literary wonders imagined by great European thinkers like Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Leonardo di Vinci.

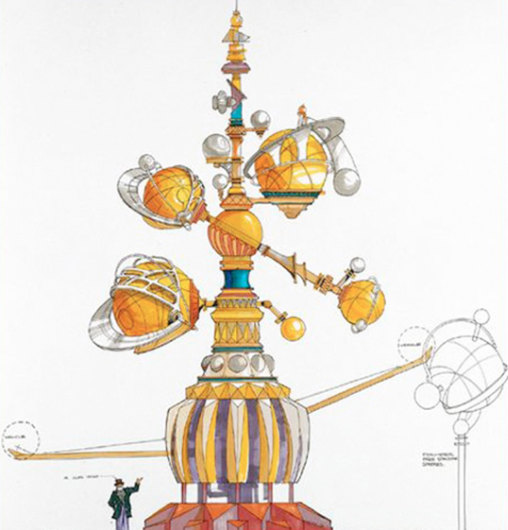

Discoveryland would be a gleaming, glowing future. Within, guests would find the custom made Lost Legend: The Timekeeper (traveling through history to find great European writers) and the grouded and golden Orbitron: Machines Volantes – revolving rockets removed from their typical sky-high position in Tomorrowland instead embedded in rockwork and modeled after a golden planetary model of old.

The land’s Cafe Hyperion was accessed through a dirigible hangar holding aloft the Hyperion airship (the starring vehicle of Discovery Bay’s E-Ticket ride, based on Disney’s Verne-esque Island at the Top of the World film), while the land’s central lagoon offered Mystères du Nautilus, a one-of-a-kind walkthrough of Captain Nemo’s docked submarine.

A world of tomorrow envisioned from the point of view of the European literary past, Discoveryland was an incredible romantic swirl of 20,000 Leagues, Tomorrowland, and Discovery Bay. And even though it would open in 1992 without a Space Mountain anchor, that’s because designers were thinking even bigger…

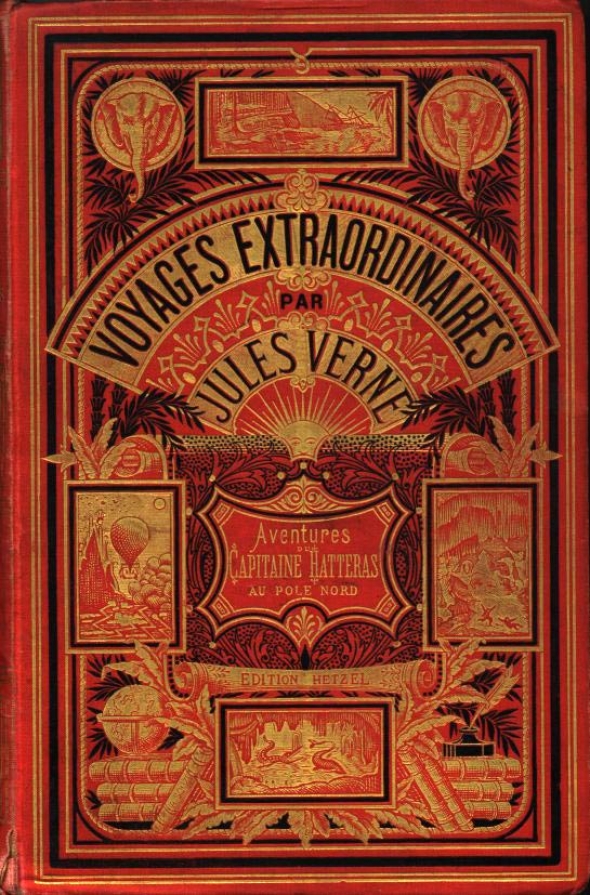

Voyages Extraordinaries

Between 1863 and 1905, famed French writer Jules Verne wrote 54 novels specifically belonging to his Voyages Extraordinaries series. Some of the best-known adventure stories today originate with this collection. In this groundbreaking works, Verne took his readers 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and to The Mysterious Island, Around the World in 80 Days and on a Journey to the Center of the Earth.

Verne’s novels are often called “encyclopedic novels” due to the great wealth of scientific knowledge presented comprehensibly by his characters… Part of the reason for the broad (and lasting) appeal of his works is the sense that the reader is actually learning about geology, archaeology, biology, astronomy, oceanography, and world cultures by reading.

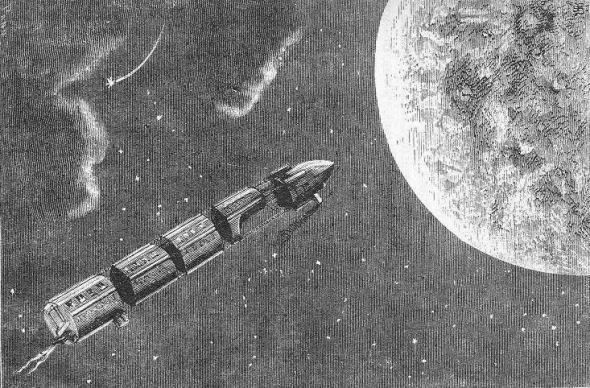

The perfect example of this unique blend of science fiction and science fact was the 1865 novel, De la Terre à la Lune (From the Earth to the Moon). The novel tells of the Baltimore Gun Club (a post-American Civil War society of weaponry enthusiasts) and their determination to build a cannon capable of launching three people to the moon inside of a missile-like projectile. Of particular interest to scientists today, Verne attempted to do some rough calculations as to the requirements of the Columbiad Cannon and – absent any available data at the time – was surprisingly close to accurate

Verne’s novel then went on to inspire acclaimed filmmaker Georges Méliès in his direction, production, writing of, and starring in the 1902 silent film Le Voyage dans la Lune. Probably the best known of Méliès film catalogue, the movie is recognized as the first science-fiction film ever and one of the most influential works in cinema history, especially thanks to its landmark moment when the cannon-launched capsule lands in the eye of the moon. (The creation of and rediscovery of the film is also pivotal in the plot of Martin Scorsese’s 2011 Academy Award winning film Hugo.)

This much was clear: a Space Mountain determined to leave science and the Space Age behind in favor of fantasy had a ready-made source material…

So even when Disneyland Paris opened in 1992 without an anchor attraction in Discoveryland, a “mountain” based on Jules Verne’s Victorian fantasy adventures was already announced as a future attraction. And this mega-attraction would be different from any attraction Disney had ever made before…

Discovery Mountain

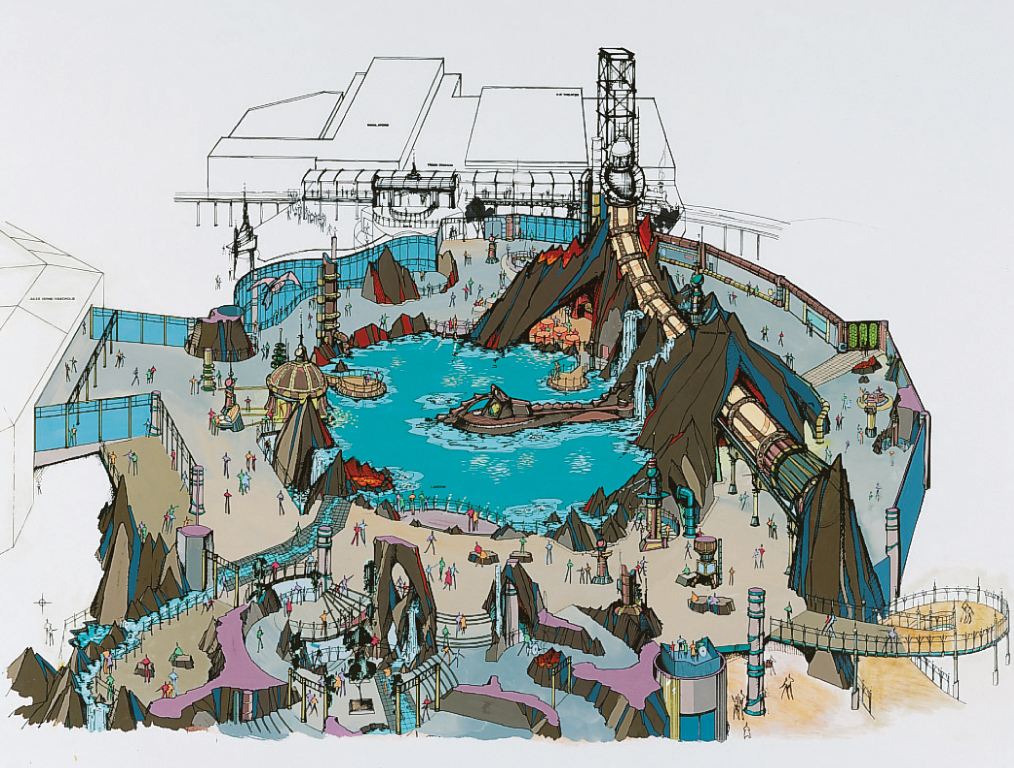

With Imagineer Tim Delaney working as the design lead on Discoveryland, a number of incredible concepts were developed for a new kind of Space Mountain that would include a roller coaster ride through the stars.

Discovery Mountain was set to become the new standard for Disney’s Imagineering catalogue. In different iterations, the concept took on different physical forms, but the high-quality, rare, Passholder-exclusive concept art shows one of our favorites – organic bleached sheet rock (you’ll notice, with geothermal heat radiating from between layers) almost resembling the iconic forms of Space Mountain… but now cracked and eroded away to reveal a golden structure beneath, formed of scaffolds, rivets, and steampunk-style metalwork.

The incredible attraction would’ve been gargantuan – twice as wide as any existing Space Mountain at about the width of a football field. That’s because, inside, it would feature a half-dozen attractions. Like an EPCOT Center pavilion, Discovery Mountain would’ve been a sub-land inside Discoveryland.

As guests stepped into the massive pavilion, they’d find themselves within the waterlogged, craggily mountainous hideaway of Jules Verne’s famed Captain Nemo. Beneath perpetual night skies, guests would’ve found an entire realm to explore, packed with a number of incredible attractions:

- A full-sized version of Nemo’s Nautilus (docked permanently with a walk-through attraction “inside”) from 20,000 Leagues;

- An underwater restaurant housed “within” the Nautilus looking out on living fish in a coral reef;

- A freefall drop tower themed to Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (which we detailed in the in-depth feature on the ride that this concept eventually evolved into the Modern Marvel: The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror);

- A steampunk train platform for the Disneyland Railroad, which would stop inside the mountain;

- A unique version of Space Mountain themed to Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon.

The grand, 300-foot diameter pavilion would’ve sincerely redefined Imagineering, on a built-out scale comparable to the would-be Indiana Jones themed land (also designed by Baxter) that would’ve created a Possibilityland: Indiana Jones and the Lost Expedition inside Disneyland California’s Adventureland.

And Tim Delaney’s Discovery Mountain was waiting in the wings, ready to be dropped into Paris to revive public interest when the resort eventually needed a boost… We’ll step onto the final attraction on the next page.