PIXAR. For a new generation of animation fans, that word appearing against a sky-blue backdrop is as comforting and familiar as “When You Wish Upon a Star’s” grand crescendo against a glowing Disney castle; a squeaking, bouncing, articulating desk lamp as recognizable and iconic as Tinker Bell; Cars Land as obvious, classic, and beloved as Frontierland.

But it wasn’t always that way… and increasingly, some fans are wondering aloud if Disney Parks are becoming Pixar Parks, favoring the computer-generated stars of Pixar’s modern classics at the detriment to Disney’s own animated favorites… So today, we’ll dig into the story of Pixar, its relationship with Disney (including some epic breakups and multi-billion-dollar make-ups), and – most importantly – trace the timeline of Pixar attractions joining Disney Parks. Is there too much Pixar in Disney Parks? That’ll be up to you to decide. But along the way, we’ll also uncover some surprising stories.

When did Disney’s connection to Pixar first begin? Longer ago than you might imagine… How many Pixar-themed attractions have Disney Parks hosted? More than you might think… How far will Pixar permeate into Disney Parks? Think, “to infinity and beyond…”

Days of Pixar past

Before Cars, Bugs, or Monsters, Pixar wasn’t Pixar at all.

The story of the making of Pixar is nearly as compelling as that of Disney Animation itself. What we know today as Pixar began in 1979 as the Computer Division of Lucasfilm – yes, the Lucasfilm of Star Wars and Indiana Jones fame. George Lucas had recruited New York Institute of Technology computer scientist Ed Catmull (today, President of Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios!) with a goal of enhancing computer-produced special effects and mastering digital editing.

Lucasfilm’s Computer Division is itself responsible for a number of technological breakthroughs in the ‘80s. Its hardware and software developments were used not only by Lucasfilm, but by its Industrial Light & Magic sister, creating a number of cutting-edge, never-before-scene computer-generated sequences in films (like a 60-second continuous computer-animated shot in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn – the first full “computer generated imagery” sequence in a feature film).

Lucasfilm’s Computer Division also attracted a few young minds eager to explore this new potential art form… in particular, a young animator named John Lasseter.

Long before 2006, when Lasseter would be appointed Chief Creative Officer of both Pixar Animation and Walt Disney Feature Animation (and long before 2018, when he’d exit the company amid misconduct allegations in the wake of the #MeToo movement), Lasseter was a free agent. In fact, the twenty-something Lasseter had only just been fired from Disney in 1983 – a move often attributed to the young, brash creative’s push for change at the dusty ole’ Disney, where Walt’s aging original animators held tight to the reins.

Suffice it to say that Lasseter was happy to join Catmull in the experimental art of computer animation… a story we’ll return to soon…

Disney’s decline

After Walt’s death in 1966, Walt Disney Productions had become notoriously rudderless. For the better part of two decades, Disney just couldn’t seem to get a foothold at the box office, releasing big-budget duds like The Million Dollar Duck, The Island at the Top of the World, The Black Hole, and The Watcher in the Woods.

Disney’s theme parks had stagnated after Walt, mostly relegated to inexpensive thrill rides (like Big Thunder Mountain and Space Mountain) in the ‘70s, rather than the elaborate, ambitious Audio-Animatronics masterpieces of the ‘60s (like Pirates of the Caribbean and the Haunted Mansion).

Worse, Disney’s once-fabled animation studio was dying. The era of Walt’s hits was over, and middling animated films of the ‘70s and early ‘80s failed to leave an impression (crescendoing with the film that almost shut Disney down for good, The Black Cauldron). Put another way, ambitious and expensive ideas about incorporating costly and experimental “computer generated” films were out of the question, and it’s no surprise that Lasseter was asked to leave.

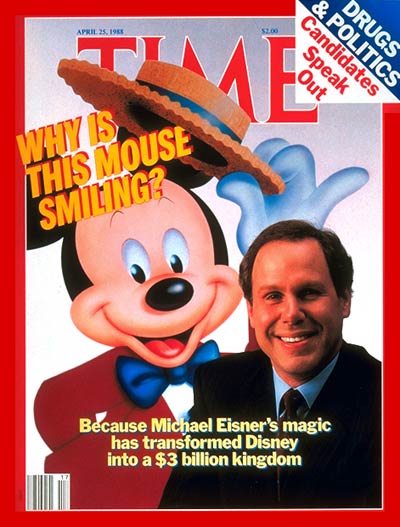

In the early ‘80s, Disney would endure a series of hostile takeover attempts that would’ve seen the company’s assets split… the only thing that stopped it was Roy E. Disney (Walt’s nephew, on Disney’s board of directors) leading a coup against then-CEO Ron Miller and hand-selecting someone with the right resume to revive Disney’s filmmaking: Michael Eisner. Coming from a time as CEO of Paramount Pictures, Eisner was brought in at Disney’s darkest moment. And to reinvigorate the studio, he needed help: Frank Wells (who became Disney’s President and COO) and Jeffrey Katzenberg (who headed up Walt Disney Studios).

Eisner came on board in 1984 and immediately began reversing Disney’s sinking fortunes. Eisner is the CEO who acquired ESPN, ABC, and Miramax (literally turning Walt Disney Productions into the international Walt Disney Company media empire we know today). He diversified the studio with the adult-oriented Touchstone Pictures banner; he revived Disney’s theme parks by bringing in the stories that mattered to modern audiences… even if they weren’t Disney stories(!), and he shepherded in the “Disney Renaissance” – the period during which the company’s animation studio was reborn with hit after hit at the box office beginning with 1989’s The Little Mermaid.

Worlds collide

In 1986 – just as Eisner’s plans for Disney were really beginning to heat up – Lucasfilm decided to spin off its Computer Division group into an independent company… one that ended up in the hands of creative visionary and Apple Inc. co-founder Steve Jobs. For just $10 million, Jobs acquired the small, 40-person team of the Lucasfilm Computer Division (including John Lasseter) and renamed it… PIXAR.

From that moment on, the stories of Pixar and Disney become entwined… but maybe not in the way you’d expect.

Pixar was testing a new Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) and Disney bought in right away, eager to see how this computer software could speed up the more mundane ink and paint process of hand-drawn animation. Just as Eisner’s Disney Renaissance was beginning, some early test shorts made by Pixar’s animators (including the fabled “Luxo Jr.” featuring the eponymous articulating desk lamp) legitimized this new CGI animation not just for backgrounds, but for characters.

In 1991, Pixar and Disney signed an agreement. Pixar would produce three computer-animated feature films to be distributed by Disney. But that’s not all.

In one of the most spectacular business decisions of the decade, Pixar negotiated that anytime “Disney” appeared on marketing collateral, “Pixar” and its logo be presented as well, and at the same size. “Disney•Pixar” was born.

In exchange for the massive distribution, Disney had its own requirement: though Pixar would create the characters and worlds seen in the films, it was Disney that would retain the intellectual property. That meant that Disney would hold the rights to create sequels based on the three Pixar films covered in the contract… with or without Pixar’s input.

1989 – The Little Mermaid. 1991 – Beauty and the Beast. 1992 – Aladdin. 1994 – The Lion King. 1995 – Pocahontas… As the Disney Renaissance continued, the animators at Pixar went about their own business, ready to introduce the world’s first full-length computer animated film. But would anyone watch?

The first three

No one had seen anything like 1995’s Toy Story before, including Disney executives. Few knew what to expect. Would families want to see a film animated on computers? Steve Jobs said of the project, “If Toy Story is a modest hit—say $75 million at the box office – we’ll both [Pixar and Disney] break even. If it gets $100 million, we’ll both make money. But if it’s a real blockbuster and earns $200 million or so at the box office, we’ll make good money, and Disney will make a lot of money.”

Toy Story ran away with a box office of $373 million – a higher gross than Disney’s own Pocahontas released six months earlier.

And due to Pixar’s clever requirement for equal billing opposite Disney, just like that, Pixar became a household name. While competing animation studios from Warner Bros. (Quest for Camelot, The Iron Giant, Osmosis Jones…) and Fox (Anastasia) tried throughout the ‘90s to match Disney, they couldn’t. Only Pixar did. Jobs said, “[W]e are only the second studio in 60 years to produce a blockbuster animated feature film – and we’re doing it in a new medium of 3-D computer graphics.”

Even more spectacularly, Toy Story wasn’t a fluke.

The next two original stories created by Pixar and distributed by Disney were A Bug’s Life (1998) and Monsters Inc. (2001) – both of which went on to score big at the box office. And it’s no surprise…! Pixar’s stories were unique, casting aside the tried-and-true fairy tales of Disney’s Renaissance in favor of quirky worlds, unusual scale, and truly original stories that (at first blush) don’t appear to fit into the so-called Seven Story Archetypes.

While the completion of Monsters Inc. also technically fulfilled the contract between Disney and Pixar, Disney had secured the rights to produce their own sequels to the three Pixar films… which meant that no matter what happened going forward, the Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, and Monsters Inc. intellectual properties were as good as theirs. And per Eisner’s cinematic understanding of the Disney theme parks, that meant that it was high time to bring Pixar to the parks… We’ll jump into the first Pixar attraction at Disney Parks on the next page…