What’s as classically-Disney as Mickey Mouse, Dole Whips, and spinning tea cups, but never shown on a Disney Parks commercial? Waiting in line.

From day one, waiting has been an essential (and for many, frustratingly memorable) component of any visit to Disneyland or Walt Disney World. And for nearly seventy years, generations of Disney’s engineers, experience designers, show writers, and executives have been trying to make guests’ waits shorter, more entertaining, more interactive, and – to the point of today’s tale – more managable.

In the great balance of guest experience, operations, and per capita spending, FastPass, FastPass+, Disney Genie+, and Lightning Lane have all taken swings at solving Disney’s supply-and-demand capacity dilemma. But altogether, Disney’s quest for the perfect virtual queue may still be ongoing, and the journey from standard queues to Genie+ is a wild ride in its own right… Today, we’ll dig into the history of waiting and explore how Disney’s 21st century solutions have created as many problems as they’ve solved.

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

Whose line is it anyway?

No one likes to wait in a line. And for most of human history, people didn’t…

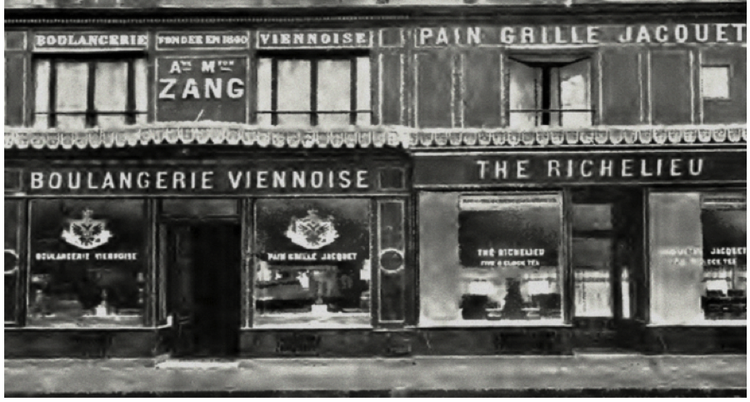

The first written account of people waiting in a single-file line comes from Scottish historian and essayist Thomas Carlyle’s 1837 book The French Revolution: A History. Carlyle described citizens of Paris forming a “queue” (French for “tail”) at a bakery, each person waiting his or her turn to purchase bread – relatively scarce in supply after the French Revolution:

“If we look now at Paris, one thing is too evident: that the Bakers’ shops have got their Queues, or Tails; their long strings of purchasers, arranged in tail, so that the first come be the first served.”

In the early 1800s, the notion of a “first come, first served” system was considered a “French eccentricity.” While we don’t exactly know what form transactions elsewhere in the world took (since that’s not a very interesting or important thing to be kept in written record), it likely involved would-be customers gathering around vendors, vying for attention like you’d find at a modern deli counter or bar.

In the early 1900s, Danish mathematician, statistician, and engineer A. K. Erlang was contracted by the Copenhagen Telephone Company to study and optimize how telephone calls were routed, ordered, and received by switchboard operators. Erlang’s “Queuing Theory” sought to make sense of how given call volumes might be fairly and expeditiously distributed among employees, helping the phone company accurately staff for predictable traffic patterns.

Queuing Theory, it turned out, informed far more than just teletraffic. By a century later, the once-uniquely-French practice of waiting “in line” had spread. Author George Orwell wrote in a 1944 essay of British citizens queuing for rations during World War II, wondering if visitors to Great Britain would be surprised by the the Brits’ “willingness to form queues.”

But across the post-War Western world, waiting in line was well on its way to becoming the norm – an everyday experience for millions in gas stations, restaurants, public transit, movie theaters, government offices, grocery stores, retailers, and, of course, amusement parks. And when Disneyland opened, there they were – lines!

The Art of the Line

When Disneyland opened in 1955, the park’s queues were made of metal posts and ropes arranged in a back-and-forth corrals, holding guests outside of, for example, Fantasyland’s dark rides. By all accounts, they were simple, old-fashioned waiting spaces. Those that remain today are charmingly naive throwbacks to the park’s mid-century origins.

As Disney legend has it, Walt’s a-ha moment around waiting came in 1960 when he visited Knott’s Berry Farm – the long-running theme park just a few miles north of Disneyland – to see the new Calico Mine Ride designed by legendary designer Bud Hurlbut. To board the slow-moving mine train, Bud led Walt under the ride’s marquee and along a winding path, weaving through fake desert rocks and waterfalls.

Only as he neared the station did Walt turn a corner to see the waiting crowd in a corral of stanchions that had been hidden from passers-by, nestled out-of-view in the false desert facade. As the story goes, Walt exclaimed, “Bud, you ole’ S.O.B.!” Walt loved that Hurlbut had hidden the wait from guests (making them much more likely to join the line and hand over a ride ticket) and that the themed pathway gave guests something more to do than to zig-zag through a slow-moving rope maze.

Decades later, Harvard business professor and author David Maister would pretty accurately sum up the rules of queueing in his Psychology of Waiting Lines, asserting that fundamentally, “People want to get started.” Knott’s Calico queue did precisely that, involving guests – however simply – in an environment that would unfurl further during the ride itself. Just being part of that space got guests started, making the wait itself that much more bearable.

It should come as no surprise that after his transformative spark at Knott’s, Walt Disney began rolling out similarly simple environmental queues in earnest in the 1960s. It’s the idea of “getting people started” that no doubt inspired the stately garden and cemetery path winding its way to the porch of the Haunted Mansion or the courtyards and fountains outside Pirates of the Caribbean.

The first truly immersive queue at Disneyland, however, was probably 1967’s Lost Legend: Adventure Thru Inner Space – one of the last projects to benefit from Walt’s direction. From that point on, incorporating the queue into the environment became Imagineering’s standard. Coupled with the new Walt Disney World’s need for weather-proof waiting spaces, rides like Florida’s Pirates of the Caribbean cemented the notion of embedding queues into decorative spaces.

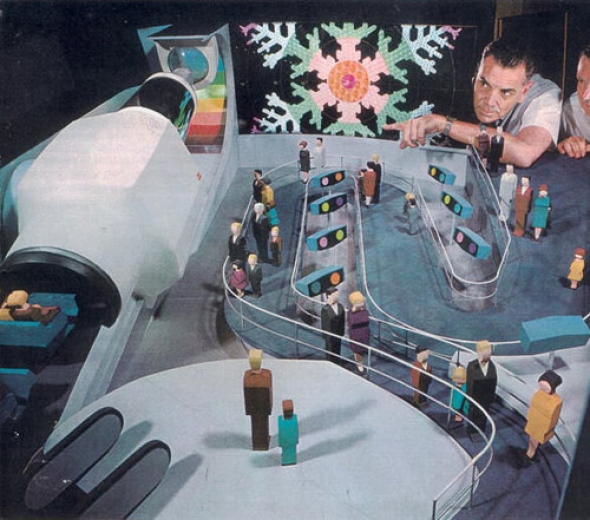

Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, new attractions like Space Mountain and Big Thunder Mountain utilized the “Calico” queue concept, trading single-file railed corrals for vaguely-interesting environments, essentially serving as quasi-pre-shows for the attractions they led toward. And that idea – that time spent waiting could at least be made more pleasant through decoration – was just the start…

Don’t wait; participate!

As with so many revolutions and reinventions at Disney Parks, the reimagining of waiting really hit high gear in the early 1990s. With then-CEO Michael Eisner at the helm, the “Ride the Movies” era was coming to fruition. An influx of intellectual properties fueled a generation of gargantuan new rides of unprecedented scale and marketability, from Star Tours to Alien Encounter; Indiana Jones Adventure to The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror. Aside from their cinematic scale, these attractions also did something brilliant: they turned waiting into part of the attraction.

Another of Maister’s rules in The Psychology of Waiting Lines offers: “Occupied time feels shorter than unoccupied time.” Like never before, this generation of ambitious attractions was designed to make the wait worthwhile, blurring environmental design, batched pre-shows, and Cast Members into the queue experience. This is where guests began to gain concrete “roles” like being an interstellar traveler or international tourist, dropped not onto one-off rides, but into original worlds and “in-universe” mythologies built-out through queue spaces.

The notion of entertaining or even involving guests while they waited was revolutionary (and remains the standard today, exemplified by Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance where it’s unclear where the “queue” ends and the “attraction” begins).

Big-budget, blockbuster E-Tickets premiered across Disney Parks throughout the ’80s and ’90s, jumpstarting a new era of Imagineering and a renewed focus on the parks. But even if Imagineers had smartly designed queues to not only hold descending crowds, but entertain them, trouble was around the corner…

What really bothered me during my sole post-fastpass trip relates to this idea that “Unfair waits are longer than equitable waits.“

If a ride goes down due to weather or maintenance, when it comes back up they prioritize the Lighting Lane and drastically increase the ratio of Lightning Lane to stand-by guests.

During my trip I had not purchased Genie+, so it was horrible waiting in the excruciatingly slow stand-by after a ride name back up. When FastPass was complimentary to everyone, this same scenario didn’t bother me, as I would also benefit from the operational change when my FastPass return time came, however, in this new system, these ‘higher-tiered’ guests were prioritized making the wait feel particularly inequitable and ergo felt way longer.

My biggest takeaway from this is how short Expedition Everest’s line was in 2015. Less than 30 minutes? Sign me up! I am glad others agree about the issues with Fastpass and I now have a place to link them to on why.

I think your solution is an interesting one. I agree that fastpasses should be cut down to larger attractions but I have never heard the idea of not opening it until the standby hits a certain time quota.

I think we could see some interesting queue changes in the future here!