When the wint’ry winds start blowing and the snow is starting in the fall, then my eyes head westward knowing that’s the place that I love best of all… California, here I come, right back where I started from! Where bowers of flowers bloom in the spring! Each morning at dawning birdies sing and everything! A sun kissed miss said “Don’t be late!” That’s why I can hardly wait. Open up that Golden Gate! California, here I come!”

When Disney’s ode to the Golden State opened in February 2001, it was supposed to change Disneyland forever. All at once, this second theme park – built right on the land that had been its older sister’s parking lot for 45 years – was meant to transform Walt’s original Anaheim property into a multi-day destination rivaling Walt Disney World in tourism and international appeal. Instead, it failed.

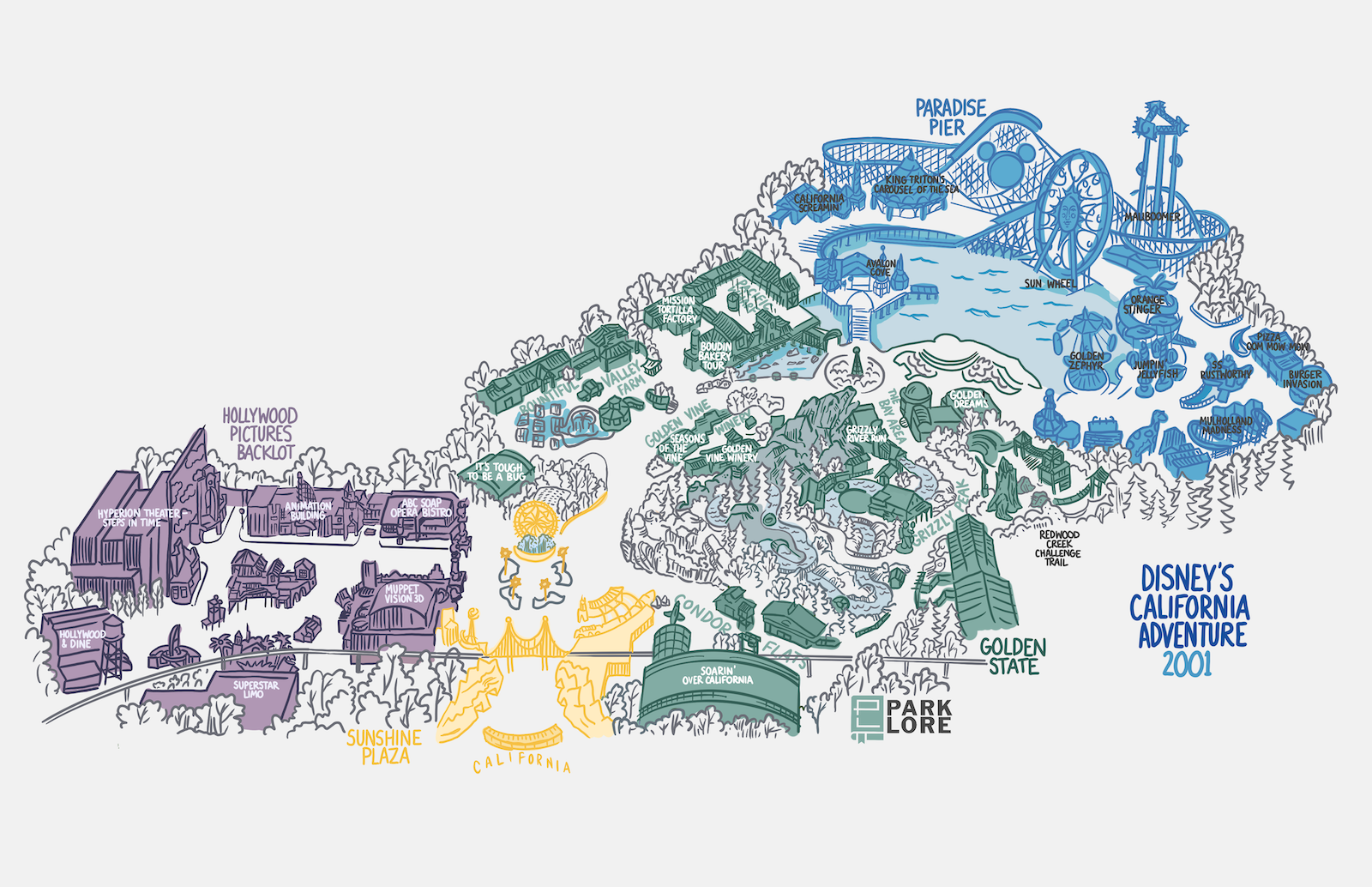

That’s exactly where our story began in Disney California Adventure: Part I – our in-depth exploration into the frustration-filled design and flawed development of Disney’s first “New Millennium” theme park. Sure, the park was “too much California, not enough Disney.” It was short on rides. It had practically nothing for families. But even Imagineers’ attempts to bolster the park’s weak spots with “Band-Aid” attractions in the mid-2000s proved that California Adventure’s issues ran deeper than ride counts… and any real fix for the park would need to address its broken foundation…

Today, in Part II of our deep dive into Disneyland’s infamous second gate, we’ll stand before the soaring, art deco towers of the Pan-Pacific and set off to explore the unprecedented process – and walk through the unbelievable outcomes – of a $1.2 billion master plan to fix California Adventure’s foundational flaws and design a true companion and complement to Disneyland… Open up your Golden Gate; California, here we come!

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

DCA 1.0

In retrospect, it’s easy to see what went wrong with the “original” Disney’s California Adventure… and easy to imagine that Disneyland’s second gate never really stood a chance.

Disneyland’s second gate was an intentional diversion from its older sister; a park so committed to post-modernity, it was willing to throw out the rulebook on five decades of Disney Imagineering and invent a whole new M.O. all its own.

Bold, bright, and flat; built of concrete and corrugated steel; packed with puns, modern music, carnival rides, and exposed HVAC… California Adventure shattered the fourth wall and invited you to explore an exaggerated spoof of the Golden State, all packed into 45 sun-bleached, highly-stylized acres of extremes. A park perfectly tailored to pre-teens of the 2000s (and approximately no one else), it was underbuilt and overconfident; a know-it-all with all the makings of a big, big problem.

If it’s been a while since you’ve visited our Disney California Adventure: Part I walkthrough, let’s quickly jog your memory…

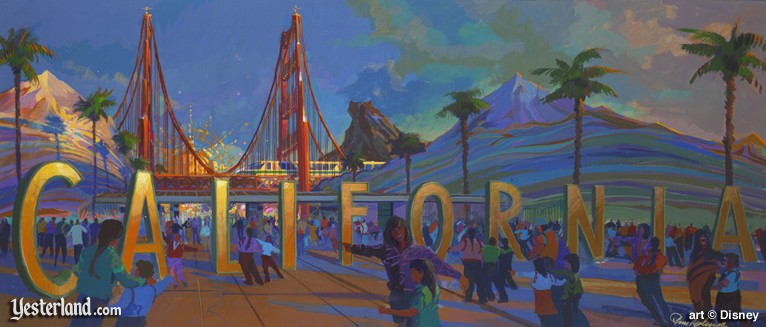

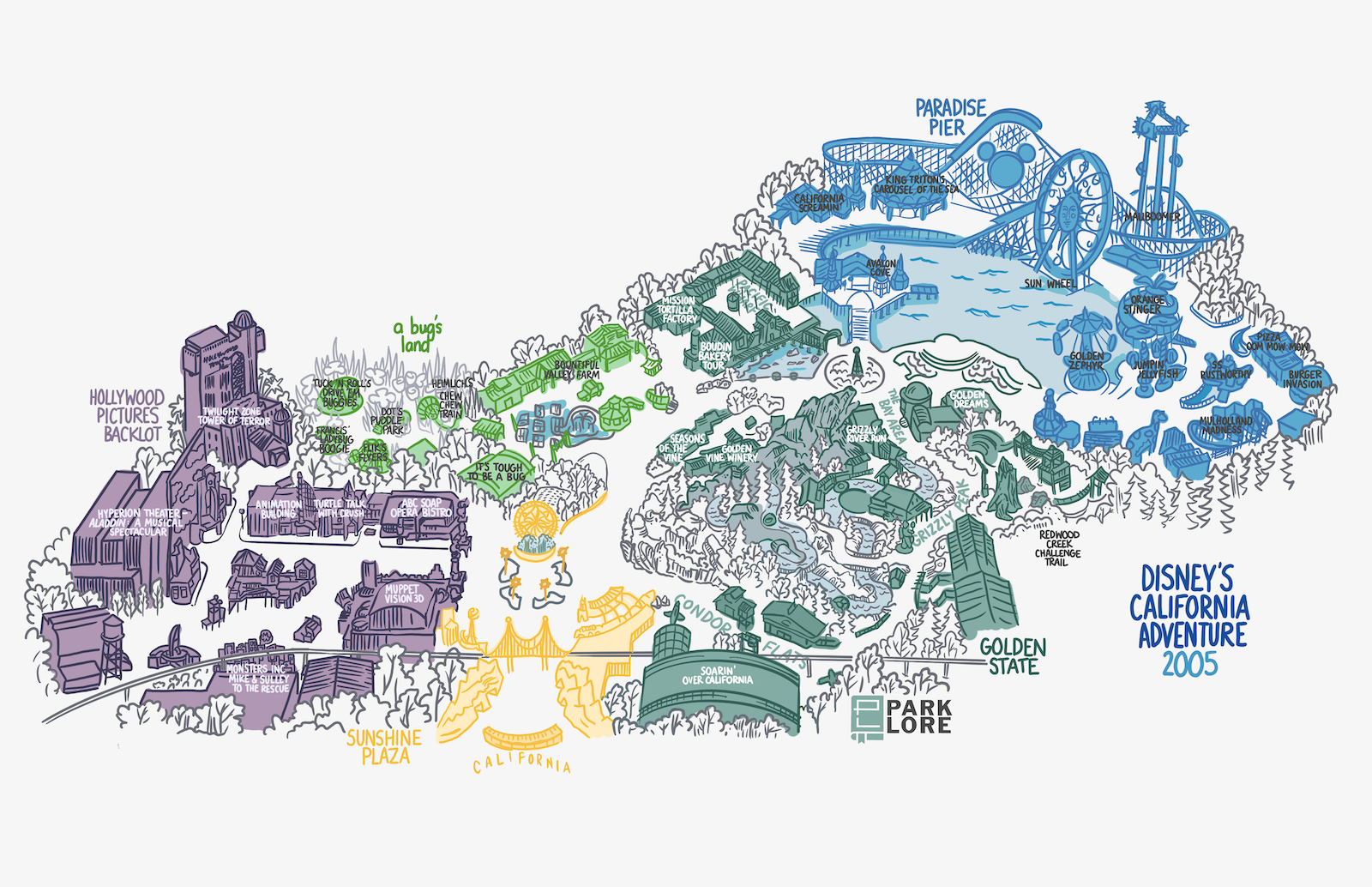

Whereas Disneyland’s opening act is the warm, glowing, historic, and nostalgic Main Street, U.S.A., California Adventure was a postmodern park with a postcard entry, leading guests to the stark, saturated, concrete Sunshine Plaza of corrugated steel walls, Beach Boys music, cartoon proportions, and the uninspiring titanium Sun Icon that just didn’t quite look or feel like a fitting counterpart to Sleeping Beauty Castle.

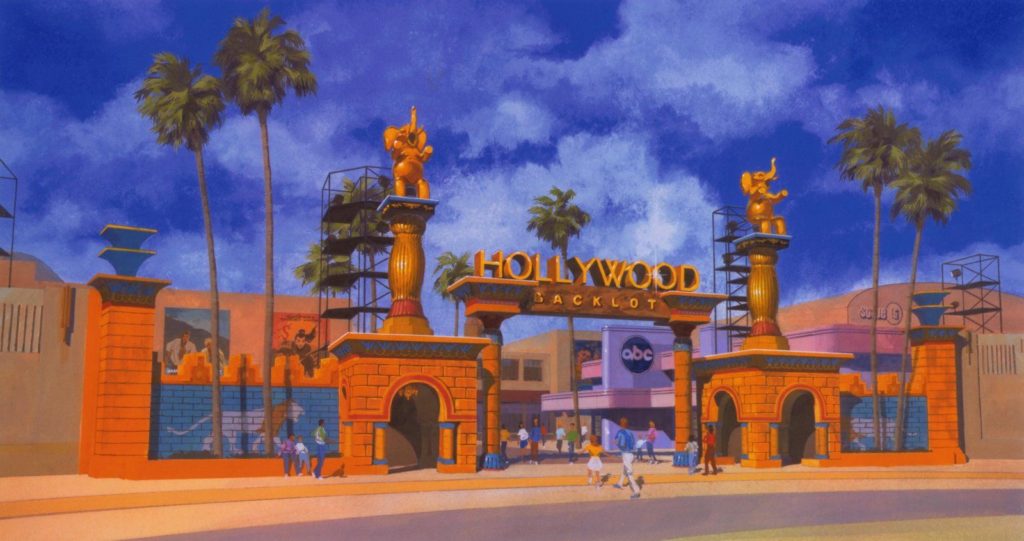

A land dedicated to Hollywood’s Golden Age is a no-brainer in a park themed to California, right? Who but Disney could transport guests to the heyday of Tinseltown, into the glitz and glamour of the movie capitol of the world? And while California Adventure did have a land dedicated to Hollywood, it was the Hollywood Pictures Backlot – a studio-style set of false fronts and allusions to the paparazzi and TMZ culture of the early 2000s, housing just one ride – a dark ride so reviled, it closed after just a year.

Next, The Golden State was the park’s catch-all district with six sub-areas dedicated to California’s “other” regions – Yosemite, Cannery Row, San Francisco, Napa Valley, the San Fernando Valley, and the High Desert. That’s saying something considering this district contained only two rides, otherwise populated entirely by restaurants, shops, wineries, walkthrough exhibits, and a sit-in tractor listed as an attraction.

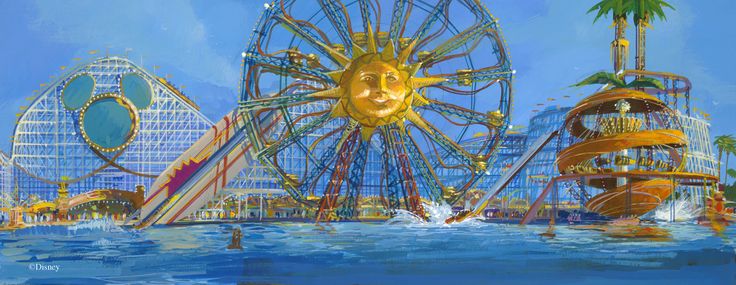

Finally, as if forgetting that Walt Disney had designed Disneyland because of his distaste for seaside amusement boardwalks, Paradise Pier made the surprising choice of setting its clocks not to some classic, historic time, but to today; a modern carnival pier of off-the-shelf thrill rides, neon signs, stucco walls, midway games, and comical, cartoon allusions to Californian landmarks.

Suffice it to say that daydreams of California Adventure elevating Disneyland into an international multi-day resort were short-lived. With poor word of mouth, practically no Disney characters, zero dark rides, and startling few rides at all – including just one of true “Disney caliber” – California Adventure was officially an albatross, regularly capturing only a third of visitors to the “old-fashioned” sister park its MTV attitude was expected to supplant.

Put succinctly by the pros at The Unofficial Guide, the park was “a bouquet of contradictions, starved in-utero by corporate Disney, and born into a hostile environment of Disneyland loyalists who believed they’d been handed a second-rate park.”

When we left off in Part I, Disney had spent the first half-year after the park’s depressing debut by doing its due diligence, adding new attractions (like “a bug’s land”, Aladdin – A Musical Spectacular, Monsters Inc.: Ride & Go Seek, The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror, and Toy Story Midway Mania!) in an attempt to bolster the park’s appeal and convince visitors to pass through the turnstile… But each read like a Band-aid on a broken bone; quick-fixes that didn’t – couldn’t – solve the park’s real problem: its missing ingredient…

The Disney Difference

The truth is, Imagineers could’ve loaded a dozen new rides and attractions into California Adventure’s four “districts” and it probably wouldn’t have done much to change the park’s reputation or its esteem among fans. That’s because – deep, deep in the park’s foundation – something was fundamentally broken; something right from the rulebook Imagineers inadvertently wrote as they developed Disneyland a half-century earlier, and that California Adventure intentionally eschewed.

You have to remember that Disneyland wasn’t built by “themed experience designers,” because that career didn’t exist. Instead, it was created by filmmakers, animators, and artists recruited ad hoc by Walt himself; craftsmen who literally wrote the rules of the “theme park” as they went. Chief among the discoveries they brought from the world of cinema was the concept of idealization. Disneyland was reassurance embodied; an idealized, romanticized place filled with idealized, romanticized places.

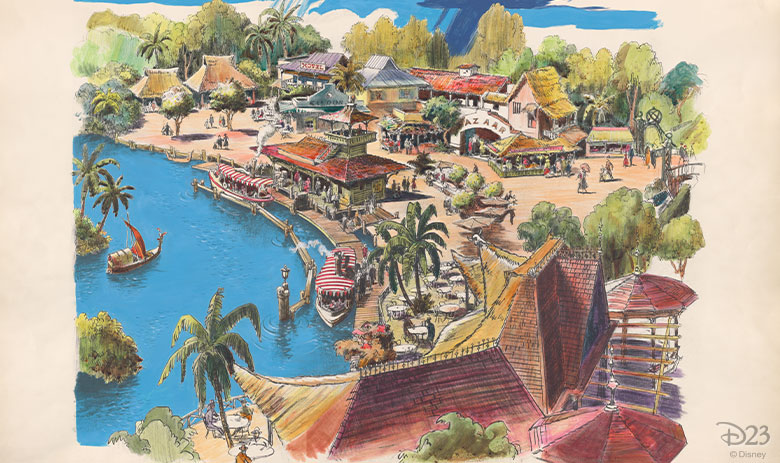

Think about it: you could scour the jungles of the world and never find a real outpost that Adventureland was modeled on; no real western town like Frontierland ever existed. Instead, the environments you step into in Disneyland are idealized, romanticized versions of places formed by our collective consciousness. Though no turn-of-the-century small town really looked like Main Street, Main Street beautifully captures what we imagine when we think of turn-of-the-century America.

The places we visit in Disneyland are part historic and habitable and “real,” but equal part fantasy, passed through a rosy lens of nostalgia and Hollywood showmanship. By design, every corner of Disneyland is infused with this filmmaker’s quality of romanticism; places that “never were, but always will be,” transporting guests to a far-off place and time that never really existed, but feels so right that never question its genre. It’s magic.

And that’s precisely what California Adventure needed. Not just new rides, but a new heart. If any foundational fix to the park were going to stick, it would need to be a complete rebirth; a floor-to-ceiling reimagining. And unbelievably, that’s exactly what it got.

Golden State of Mind

When Bob Iger succeeded Michael Eisner as CEO of Disney in 2006, he inherited a company whose best days appeared behind it. Disney had entered a historic slump post-Renaissance. With Disney’s own animated films faltering at the box office, Disney’s production partners at Pixar seemed to have surpassed their one-time mentor… and thanks to Eisner’s increasingly-icy relationship with Pixar founder Steve Job, Pixar was ready to walk out the door and change their relationship with Disney into a competitive one.

Likewise, Iger inherited control of three underbuilt and underperforming New Millennium theme parks, each serving as a strangling hinderance to the company: Walt Disney Studios Park, Hong Kong Disneyland, and of course, Disney’s California Adventure.

Reflecting on the state of the park, Iger later told the Wall Street Journal: “Steve Jobs is fond of talking about brand deposits and brand withdrawals. Any time you do something mediocre with your brand, that’s a withdrawal. California Adventure was a brand withdrawal.”

The newly-minted CEO recalled in The Imagineering Story that he quickly did his due diligence, requesting a financial analysis regarding the potential for a massive influx of capital expenditure for the park. The report suggested that the payoff for such an investment was likely to be a poor one. But, “I ended up essentially ignoring that. I listened to it, but I decided not to take it into account when the decision was made to try to fix it, because the problem was too big for us image-wise – sitting right next to Disneyland.”

In 2007, Bob Weis (above) – who’d joined Imagineering in the 1980 staff-up to EPCOT Center but left in 1994 to head his own firm – boomeranged back to WDI, lured by the possibility of serving as the division’s Executive Vice President and helming a complete rebirth of Disneyland’s cursed second gate. Arriving with fresh perspective, he was able to analyze the deeply-rooted issues that plagued the park and that couldn’t be solved with new rides alone.

“California Adventure did not have the sense of place or warmth or just the Disney bubble that Disneyland had,” he told Leslie Iwerks. “When you put something that just doesn’t have that right across the plaza from Disneyland, it just feels discordant. So people weren’t comfortable there. And so you found that guests didn’t really like the place – and I don’t even think the people who worked there liked the place very much. No one wanted to stay there to dine or shop. They just wanted to come, do Tower of Terror, Soarin’ – you know, those main things – and then get back to the richness of experience and optimism that you feel when you walk around Disneyland.”

Of the “MTV attitude” that had been imagined as California Adventure’s hallmark a decade earlier, Weis took issue. “The language used and the graphics were kind of insincere and jokey, and some of the attractions had kind of weird humor. It just didn’t feel like it had the earnest warmth that Disneyland present.” California Adventure’s spoofy, fourth-wall-breaking, postmodern coldness had to go.

Iger distilled his mandate to Weis and the team assembled around the California Adventure project into six words: “Big ambition. Big risk. Sweeping change.” And that’s exactly what was announced.

At a press conference in October 2007, Disney executives did something they’d never done before: they admitted defeat. Waving the white flag, Iger announced that Disney’s California Adventure would undergo a master-planned metamorphosis. The park that had cost $600 million to build just six years earlier would now be gifted $1.2 billion in reinvestment, effectively tripling its embedded value. The two capstones of the project would be a new entry land (Buena Vista Street, replacing Sunshine Plaza) and the headlining Cars Land (a massive, 12-acre “Living Land” dedicated to Disney / Pixar’s Cars).

But that unimaginable influx of cash would not just supply new rides, attractions, shows, and restaurants… it would also power something much more intangible: a new spirit… How did it come together? Read on…