2007 was a big year for Imagineering fans.

On May 31, Universal announced that it had acquired the worldwide rights to build theme park attractions based on Harry Potter… but that they wouldn’t just be building mere attractions. Instead, they’d be designing first-of-its-kinds, totally-immersive, “living lands” devoted to the franchise, letting guests step into the world seen on screen.

On October 17, Disneyland officially unveiled plans to completely redesign their own underbuilt and under-designed theme park – the Declassified Disaster: Disney’s California Adventure – in a five-year, $1.2 billion intentional reimagining. Not coincidentally, it would be centered around their own “living land:” Cars Land. The massive, all-at-once, master-planned rebuild at California Adventure would fix the park’s flawed foundation of being (you guessed it) cheap, and lacking Disney quality.

And right in between those two monumental moves in the industry, Pixar’s newest film hit theaters…

Ratatouille

Ratatouille is a stewed vegetable dish originating in Nice, France, comprised of onions, zucchini, eggplant, peppers, fennel, basil, and sautéed garlic cooked together with a tomato base.

Until 2007, that is, when it was redefined in pop culture thanks to the eponymous Disney•Pixar film. That animated feature produced and directed by Brad Bird (The Incredibles and Tomorrowland) follows the exploits within Gusteau’s – a fancy French bistro whose recently deceased namesake just so happens to have inspired a rat named Remy to become a chef himself. Needless to say, rats aren’t exactly welcome in fancy French bistros, leading to Remy’s team-up with a young garbage boy / wannabe-chef named Linguini.

Though – arguably – Ratatouille hasn’t been as enduring in pop culture or in Disney’s long game (read: merchandising) strategy as Cars, Monsters Inc., Toy Story or Nemo, the film was nonetheless yet another clever addition to Pixar’s nearly-uninterrupted pattern of releasing top-notch, unexpected animated films that feel like they exist outside of any pre-existing formula or familiar plot.

Oh, and in France, the film broke records as the highest grossing animated film ever. Viewers, the press, and – most surprisingly – prominent French chefs gushed over the film, turning it into a must-see culinary sensation across the country.

And like most of Pixar’s portfolio, Ratatouille earned nearly perfect critical reception, was nominated for five Academy Awards (winning one – Best Animated Feature), and made $650 million at the box office against a $150 million budget.

Gathering ingredients

As Ratatouille left European cinemas, Disney Imagineers were putting the finishing touches on yet another piecemeal expansion of Walt Disney Studios – this time, an even more overt product of the “Pixarification” of Disney Parks. Toy Story Land actually had its world debut in Paris (and has since gone on to join almost every Disney Resort), which also exemplifies the land’s purpose: it’s been used time and time again as Disney’s go-to for quickly and inexpensively adding ride capacity to underbuilt parks.

With its lightly dressed, “off-the-shelf” fair rides and its “lite immersion,” cynics might say that Toy Story Land is Imagineering’s go-to tool for adding something “cheap and cheerful;” bright, kinetic, and tied to a beloved IP, but largely empty calories.

However, Toy Story Land was also the biggest and most consequential Pixar presence in Disney Park’s yet. That got Imagineering executive Tom Fitzgerald and Pixar’s ambassador to Imagineering Roger Gould in the same room, wondering if Ratatouille might be a natural next step for the Parisian park…

With Ratatouille a condender for a spot in Disneyland Paris (and a potential waymarker for the future of Walt Disney Studios), concepting began around 2009. Even then, designers had to know that a lot was riding on their Ratatouille ride. It would need to be different; it would need to be exclusive; it would need to be big. Basically, whatever they came up with had better be good. Luckily, they knew the recipe.

1. The setting

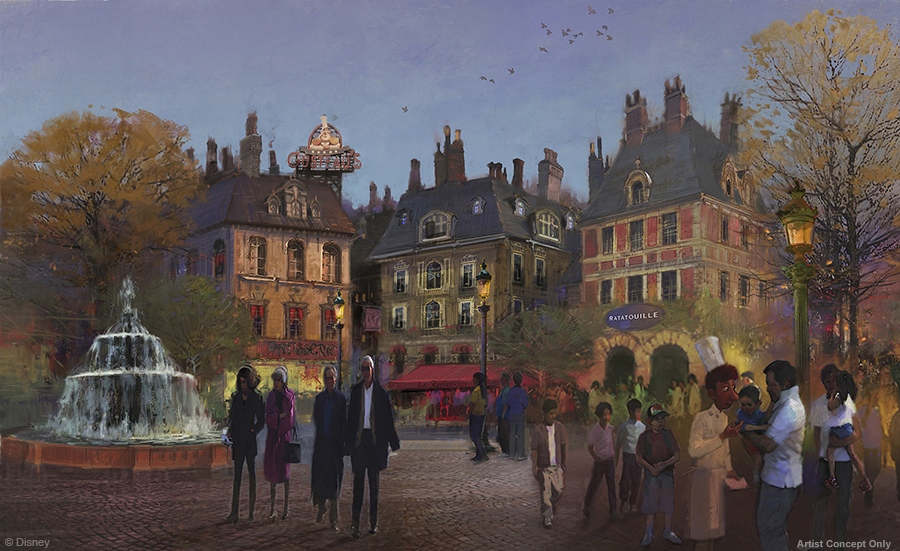

What Imagineers began to develop was finally a shift away from the studio styling of the ’90s… Perhaps inspired by Toy Story Land, and the in-development Cars Land and Wizarding World, plans coalesced not around a mere expansion to Toon Studio, but something much more grand: the opportunity to step into the dazzling, romantic, culinary City of Lights as it had been romanticized and idealized in Ratatouille – a formula straight from Disneyland 1955’s playbook.

La Place de Rémy was born… This quaint Parisian boulevard wouldn’t look like a physical spot in Paris, but rather, like the Paris we all envision; brushed and blurred to perfection; a courtyard of fresh bread, wine tastings, and bubbling fountains; a mini-land with all the charm Imagineering could muster, and a reprieve from the cold studio style elsewhere.

Now all Imagineers needed to do was to create a ride. And boy, if the future of Walt Disney Studios Park was riding on it, it had better be a good one..

2. The system

The first breakthrough behind a headlining Ratatouille ride wasn’t really a breakthrough at all. In fact, Disney had debuted its LPS (local positioning system) ride system back in 2001 at Tokyo Disneyland, where the starring technology had elevated a Winnie the Pooh dark ride from typical Fantasyland fodder to an international E-Ticket. Guests seated in “hunny pots” would find themselves drifting along water channels, “bouncing” with Tigger, dancing around Huffalumps and Woozles, and moving fowards, backwards, left, and right.

LPS rides are characterized by dispatching multiple vehicles at once into a ride, where RFID-transmitting pucks or Wifi systems coordinate complex movement patterns. This allows LPS dark ride vehicles to divert down different paths, engage in “near miss” moves with props and other vehicles, “dance” in coordinated patterns, and more. The sensational experience has been so integral to Imagineering’s best, we devoted an entire Extra feature to the best (and worst) trackless dark rides, and listed the technology among our Seven Modern Wonders of the Theme Park World.

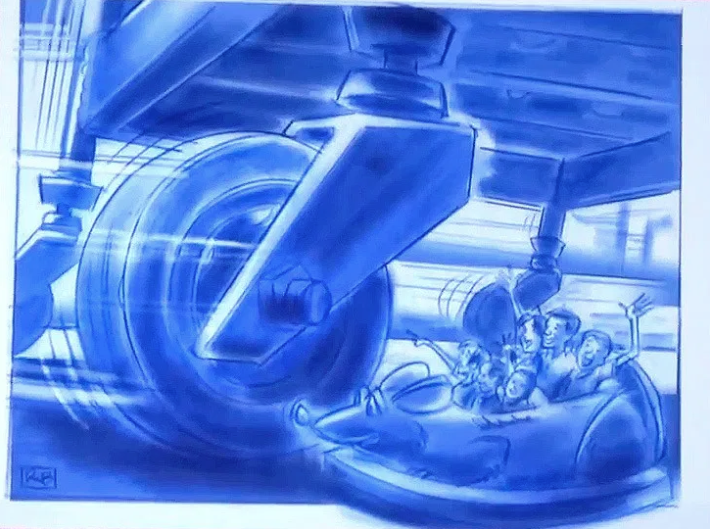

The sensational technology of an LPS dark ride was so comeplling, it was a shoe-in for Ratatouille; the perfect experience to position the park as a “must-visit” with its own exclusive headliner. Imagineers designed “ratmobiles” that would help guests see themselves scurrying along the rooftops of Paris.

By the way, the LPS technology wasn’t only being deployed in Paris; in about the same timeframe, it was being installed in a ride meant to right the other cop-out park of the 2000s – Hong Kong Disneyland – by way of 2013’s Modern Marvel: Mystic Manor. In fact, the success of Hong Kong’s dark ride had not just inspired Imagineers to re-use the technology in Ratatouille, but to upsize the scenic design… literally.

3. The scale

According to the indispensible Leslie Iwerks docu-series, The Imagineering Story, Paris’ Ratatouille ride was initially devised as using the trackless, LPS ride vehicles and setting them down in an oversized world comprised entirely of massive scenes and gargantuan props, making guests feel that they’d shrunk to the size of a rat. Guests would dart beneath three-story tall tables, race beside towering mops, and zig-zag through kitchen store rooms, gazing up at the massive world around them.

As vehicles made their way through the kitchen, they’d encounter plenty of all-physical effects, giant sets, and towering Audio-Animatronics.

But to hear Pixar’s Roger Gould speak to The Pixar Times, “There was probably a year or more that was spent exploring the idea of building it as a purely physical giant oversized kitchen, with giant moving parts – giant chef’s legs are about to step on you and other giant animatronic figures. The problems that we kept running into were that the speeds of these giant mechanisms were just too slow to recreate the dynamic feeling that you have in the film.”

And you can imagine why! To support fifty foot tall figures – much less animate them – would be a collosal feat of engineering, to say nothing of the size of the ride building. Basically, the bigger things get, the harder it is to move them quickly. To present the frenetic, skittish, zipping experience of being a rat racing underfoot in an active kitchen, giant props and figures just wouldn’t convincingly fit the bill.

So while the new attraction would still shrink guests and include a massive, oversized scale, it would need something else to bring the rat-sized world to life.

4. Squiching

Designers opted for a distinctly 21st century solution. Though “squinching” may not sound like a pleasant process, it’s actually the animation innovation that powered one of the greatest and most groundbreaking modern dark rides of our time – 1999’s Modern Marvel: The Amazing Adventures of Spider-Man.

The idea was revolutionary. On board Universal’s Spider-Man attraction, guests would be seated in dynamic, motion-based vehicles that would pass through physical dark ride scenes where embedded screens would be hidden, acting as “windows” that would stretch the scene well beyond the limits of practical sets. Action on-screen would be reflecting in reaction in the real world – from movement to light to sound – blurring the line between the “real” world and the “animated” one.

But crucially, the idea of “extended” an alleyway or warehouse on screen required a new consideration. Since riders would approach, back away from, and pass across these screens, the scenes themselves needed to reflect viewers’ shifting perspective. The notion is that if you watched a Spider-Man scene loop from a single point of view, the alley would appear to stretch and skew; to bunch up and then expand. But from the moving point-of-view of riders, this “squinching” simply makes the shot appear dimensional and real.

It stood to reason that by merging Disney’s patented LPS ride system with the general flow of Spider-Man and its “squinching,” Pixar animators could create the world of Ratatouille with all its frenzy, energy, and movement in tact. Key sets and giant props could still make the ride more than a simulator, but the role of multimedia became the ride’s coup.

Bon Appétit

In March 2013 – about six years after the film’s debut – it was official. Walt Disney Studios would indeed add a new attraction themed to the 2007 film – Ratatouille: L’Aventure Totalement Toquée de Rémy. (It’s a pun! Get it? No? In French, “toque” means “crazy,” but also is the name of a chef’s hat. The rest we can discern from context.)

The build would certainly be one of the largest in Disneyland Paris’ history, thanks in part to the massive props that would bring the kitchen and dining room of Gusteau’s to life (see the incredible Passholder-exclusive construction photo, below).

Now, those sets would merely be interspersed with large, domed and curved screens up to 35 feet tall for three “ratmobiles” at once to park in front of. The film’s production designer, Harley Jessup, was brought in to consult. Throughout the process, it was important for designers to capture the hand-built feeling of Paris not only to remain true to the film, but because the ride needed to communicate that Walt Disney Studios was at least on a new path…

Ratatouille would be a true headlining dark ride that would instantly rocket to the top of the park’s billing. It opened on July 10, 2014 as the new headliner of Walt Disney Studios and of the entire Disneyland Resort Paris. What awaited within? We’ll take a ride together on the next page.