The Tomorrowland Problem

Standing at the close of the 1970s, the Tomorrowlands at Disneyland and Magic Kingdom were outstanding examples of forward-thinking design to audiences of their respective times. If you can imagine, Walt and his Imagineers had predicted the look and feel of the Space Age surprisingly well (and in so doing, had likely shaped it, too) and were equally in-touch with futurism in each subsequent remodel.

The trouble is that eventually, “tomorrow” always becomes “today.”

Think about it: The Space Race had seen the United States and Soviet Union sprint toward the moon throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s, but by the ‘80s, the moon had lost its luster in the eyes of the public. The moon was the stuff of yesterday’s headlines, leaving the Flight to the Moon attraction at both Disneyland and Magic Kingdom old news, not staggering futuristic breakthroughs. Both attractions, in turn had to be redesigned as Mission to Mars in 1975.

Even the unassuming Autopia – which seems at first glance to be entirely out of place in Tomorrowland – was at one point a sincere display of progressive dreams. In 1955, President Eisenhower had not yet signed the Interstate Highway Act that would see multi-lane highways criss-cross the country. Disney’s complex circuit of overlapping bridges and on-ramps was unimaginable in the ’50s. But by the 1980s… Not so much.

By the 1980s, a public increasingly aware of (and wary of) unrestrained corporate power and the inherent dangers of atomic energy found the Monsanto-sponsored Adventure Thru Inner Space to be a hokey remnant of the 1960s, not a futuristic, cutting-edge exploration. Time had caught up to tomorrow.

What’s worse, the very concept of “tomorrow” had been redefined in the decades since the Tomorrowlands’ respective redesigns. While Disney had designed from the point-of-view of an optimistic world shaped by pop culture images of glowing white rockets and plastic utopian cities of the future, things were changing fast.

Entirely counter to the optimism and ambition of the Space Age, pop culture had something new in mind. Films like Blade Runner, Terminator, Alien, and even Star Wars charted a new course for humanity’s future: dystopian cities awash in steaming pollution and overpopulation; hulking, hissing spacecrafts of labyrinth-like corridors; sinister empires, amoral governments, or evil corporations using technology to terrorize the frightened inhabitants of wasteland worlds.

To children growing up in the 1980s, Disney’s so-called Tomorrowland was a remnant of the past, operating retro attractions filled with decades-old style and in a setting contrary to their own imaginations. That meant that yet another floor-to-ceiling facelift would be needed… and if the past were any indicator, it wouldn’t be the last.

Put another way, Tomorrowland was inherently broken. Disney would either need to commit to continuous, perpetual periodic upgrades to keep the lands aligned with science and pop culture… or would need to find a way to make Tomorrowland timeless.

Everything old, new again

Though it may not seem important, our road to tomorrow needs to make a quick detour to the past.

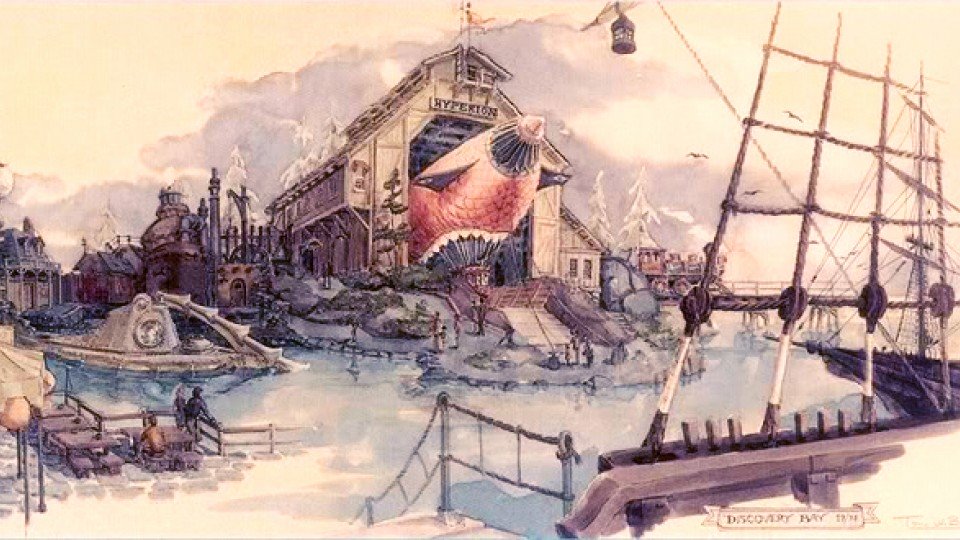

Way back in the 1970s, a young Imagineer named Tony Baxter had been envisioning a monumental project for Disneyland: an entirely new land to be built along the park’s Rivers of America. That Possibilityland: Discovery Bay would’ve been something new: a steampunk-stylized land borrowing from the lore of Jules Verne’s romantic adventure novels of the late 1800s. A retro-futuristic port of inventors, eccentrics, and immigrants, one of the land’s highlights was reportedly meant to be a ride aboard Captain Nemo’s famed Nautilus.

But unlike the Lost Legend: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea that Baxter had helped designed for Magic Kingdom, this journey through the ocean wouldn’t be a sincere submarine ride (after all, Disneyland’s Submarine Voyage already ticked that box). Instead, it would be something unprecedented: a simulator, with riders in a box rumbling along to an in-cabin projected film, as used by pilots in flight training.

Suffice it to say that Discovery Bay never came to be. In the 1970s, Disney was in the midst of immense pressure thanks to a never-ending stream of box office bombs (including The Island at the Top of the World – a film that would play into Discovery Bay’s narrative), leaving investment in the parks stagnant. It wouldn’t have mattered anyway, since the technology to power the land’s simulator just wasn’t readily available in the mid-’70s.

However, Tony Baxter and then-CEO Ron Miller did begin talks with George Lucas (creator of Star Wars) about how his properties might fit into Disneyland, including as a good fit for Baxter’s simulator concept. But talks stalled as Disney’s decline continued, and as the company underwent a massive redirection…

Here’s where we reach a definitive turning point in the development of Disney Parks. In 1984, Walt’s nephew Roy rallied Disney’s board to oust its ’70s leadership and take a risk on new blood. Frank Wells (left) and Michael Eisner (right) became the president and chairman of Walt Disney Productions, respectively. The duo inherited a Disney in disarray, and needed to right the sinking ship… quickly.

With extensive histories in the film industry, both Wells and Eisner had all the ingredients needed to reverse Disney’s sinking studios… and to bring pop culture relevance back to the parks. Forging an unprecedented agreement with George Lucas, Disney’s new leadership did the unthinkable: they brought non-Disney characters into Disney Parks.

Tony Baxter finally got his simulator. But that’s not all; the introduction of Star Wars into Tomorrowland literally changed everything at Disney Parks. That’s why the Lost Legend: STAR TOURS is remembered as simultaneously kicking off the “Ride the Movies” era, the Age of the Simulator, and the idea that Tomorrowland didn’t necessary have to feature actual, intentional, scientific predictions.

So while STAR TOURS opened a path to the future that did not rely on literal “scientific predictions of things to come,” Baxter’s plans for Discovery Bay weren’t entirely lost, either. After all, when it came time to build a brand new Disneyland-style park near Paris, Baxter was chosen as the lead designer… and given that the Tomorrowlands back home still reeked of mid-century Americana and hints of the Space Race (which would be of zero relevance to Europeans), Baxter’s team revisited those retro-futuristic plans once again… See how we got back on track?

1992: Discoveryland (France)

Location: Disneyland Paris

Lifetime: 1992 – present

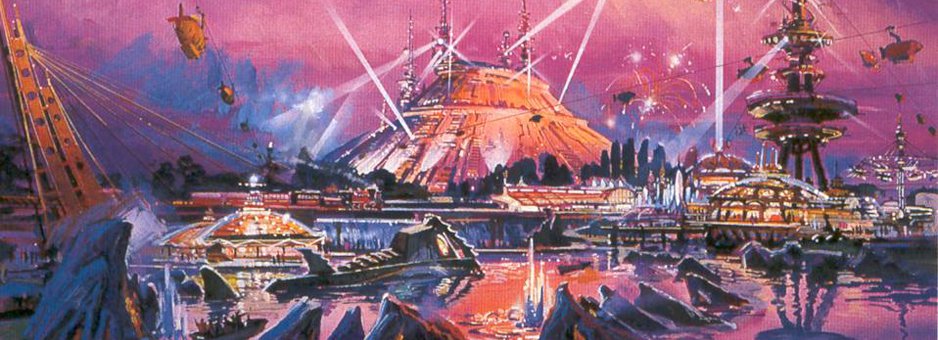

Forget sleek, white, geometric cities of tomorrow. Forget the style and science and innovation and optimism of the Space Age. This is not Tomorrowland. This is Discoveryland. Discoveryland is a land of the future rooted in the past. Imagine how the future would’ve been envisioned by great European thinkers and literary dreamers like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells.

Through their stories of time machines and hot air balloons; submarines and scientists emerged a land of bubbling lava lagoons, organic windsail towers, iron-rich red rocks jutting from the ground, sprawling gardens, fantastic zephyrs, and wild, steam-powered inventions.

More than just style, the land had substance, too. Its attractions were literary and romantic and thoughtfully integrated into this retro-futuristic realm. Take the Lost Legend: Le Visionarium, a time-traveling journey through the story of European visionaries (and the first use of Disney’s Circle-Vision cinema for a story-based attraction), or Les Mystères du Nautilus – a walkthrough of Nemo’s submarine complete with giant squid attack.

Rather than the NASA-inspired Rocket Jets that revolve high over Tomorrowland, Discoveryland features the Orbitron: Machines Volantes. Like the rest of this gleaming literary world, it looks like something drawn from a fantasy novel; a swirling kinetic sculpture of bronze orbs aligning like an ancient astrolabe plucked from Da Vinci’s sketchbook.

It’s not lofted above the land, but dug down into an earthen berm of astrological symbols, surrounded in geometric red rocks having burst geologically forth from the earth around it. It’s grounded – literally – within this harmonious, naturalistic, literary future.

Finally, there was the pièce de résistance – the Lost Legend: Space Mountain – De la Terre à la Lune. Here, the attraction was not anchored in the scientific adventure through the stars like Disneyland’s, but based on the Jules Verne novel in which members of a Massachussetts aristocratic club are blasted from the towering bronze Columbiad Cannon into the fanciful stars for a trip to the moon.

Fittingly, Discoveryland’s mountain is not a sleek, white, Googie peak. Instead, it’s made of bronze and copper rivets and panels anchored by cogs and screws, and with the elegant bronze cannon resting along the mountain’s slope, launching trains up the side of the mountain and into the dark core. Like the rest of the land, it was beautiful, unique, literary, and smart.

But far more importantly, it was timeless. It’s a fantasy future, inherently avoiding any actual predictions of science or technology. It’s a vision of the future rooted in the past; thus, one that could never come true and would never need updating. And it would be the model for every Tomorrowland on Earth to follow.

Back to the drawing board…

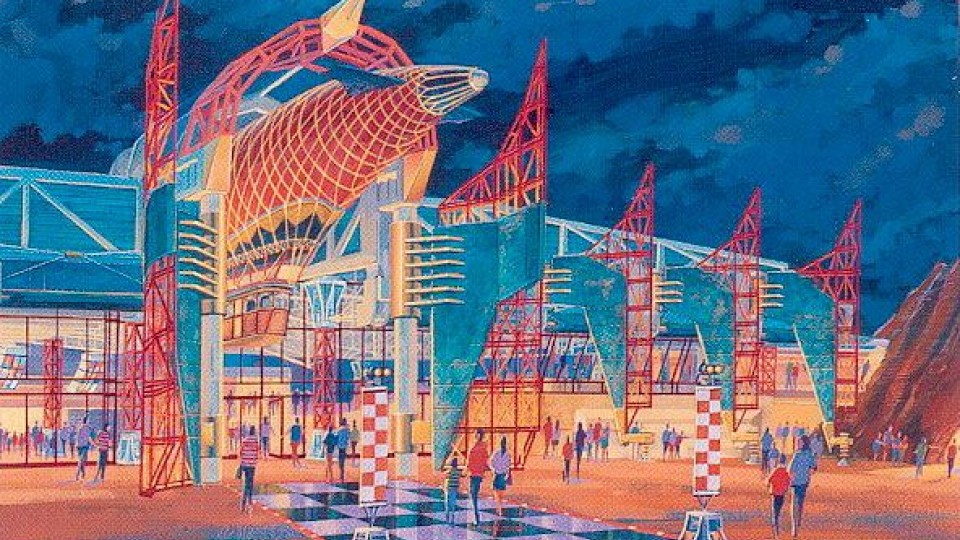

Spurred on by the possibility of creating a timeless Tomorrowland that would never need updating, Imagineers set to work to design equally everlasting styles for the Tomorrowlands in California and Florida.

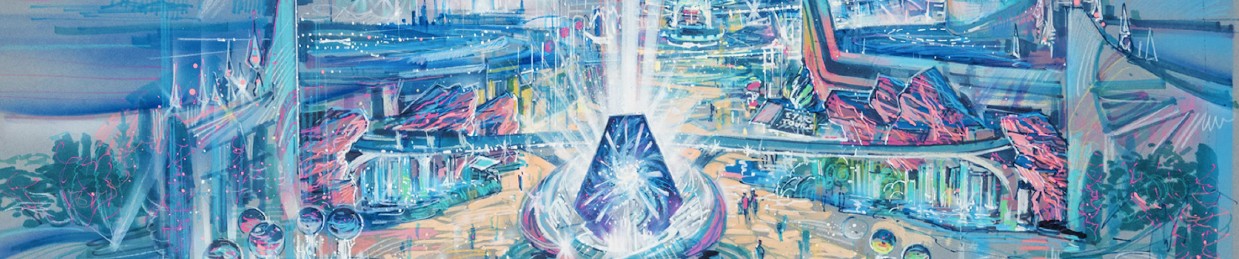

With Tony Baxter on board to design it, it was announced that Disneyland would become home to another new version of Tomorrowland; a third redesign in the park’s 40 year life. Construction would begin in 1993 on a grand, new vision of the future to be opened in 1995. Tomorrowland 2055 would defy expectations and – most importantly – give Disneyland a timeless Tomorrowland that would last forever.

So what would guests have found in this new vision of tomorrow? We’ve got all the information you can find on the next page. Let’s step into Tomorrowland 2055.

Solarpunk! – lots of sleek white/glass with a bit too much greenery + plus an ecological message is quite timeless.