Here at Park Lore, our growing list of in-depth features is committed to an ambitious project: capturing the complete stories of forgotten fan-favorite attractions and telling those tales in one-of-a-kind, in-depth features that we call Lost Legends. We’ve been thrust to the dawn of time aboard Universe of Energy and Back to the Future – The Ride; we glimpsed tomorrow itself with Captain EO, T2 3-D, and Horizons…

But the subject of this Lost Legend brings the past and future together as never before. The Timekeeper was a cross-dimensional, time-traveling, cultural adventure starring Robin Williams that turned ’50s technology into a showcase of yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

Equally at home in Disneyland Paris’ glittering, golden retro-future and the industrial, factory pomo tomorrow of Magic Kingdom, the attraction was timeless… until it disappeared. Buckle up, because – like all of our in-depth features – the story of The Timekeeper begins long before the attraction ever opened…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

Light & magic

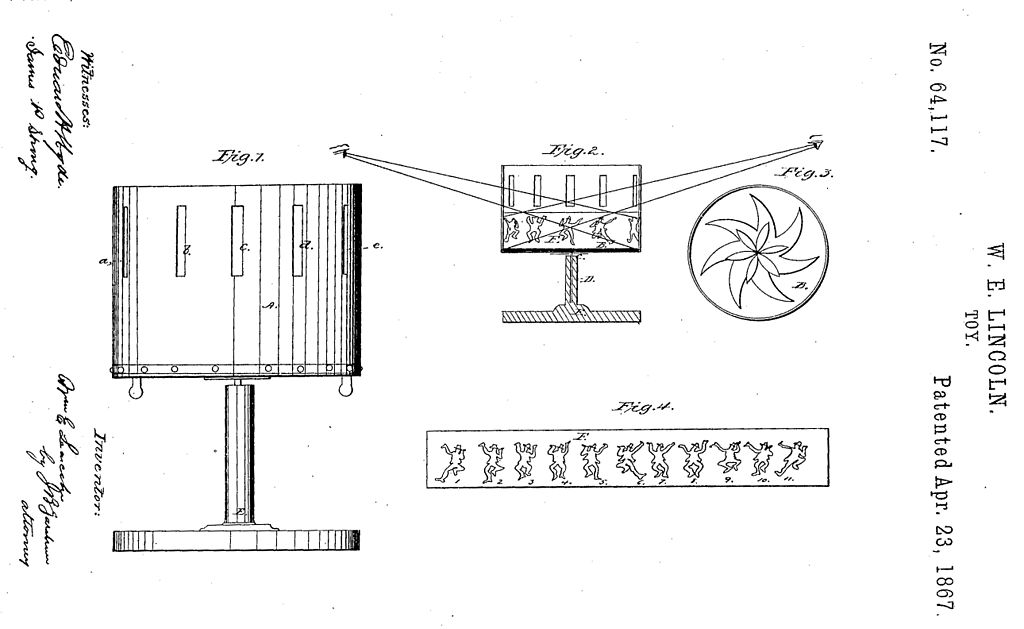

In 1867, a twenty-year old named William E. Lincoln (a college student at Brown University) submitted drawings to the U.S. Patent Office for a device he hoped to sell to toy manufacturer Milton Bradley and Co. A simple spinning cylinder with slits cut around its circumference, Lincoln’s “zoetrope” would come with long strips of paper printed with a series of images – each one only slightly different from the one before… For example, each showing a snapshot of a horse in motion as it trots.

When this series of snapshots was nestled along the inside of the device’s cylinder, a simple spin and a gaze through the quickly-passing slits would make the images appear to blend together as one moving picture… An early example of modern animation.

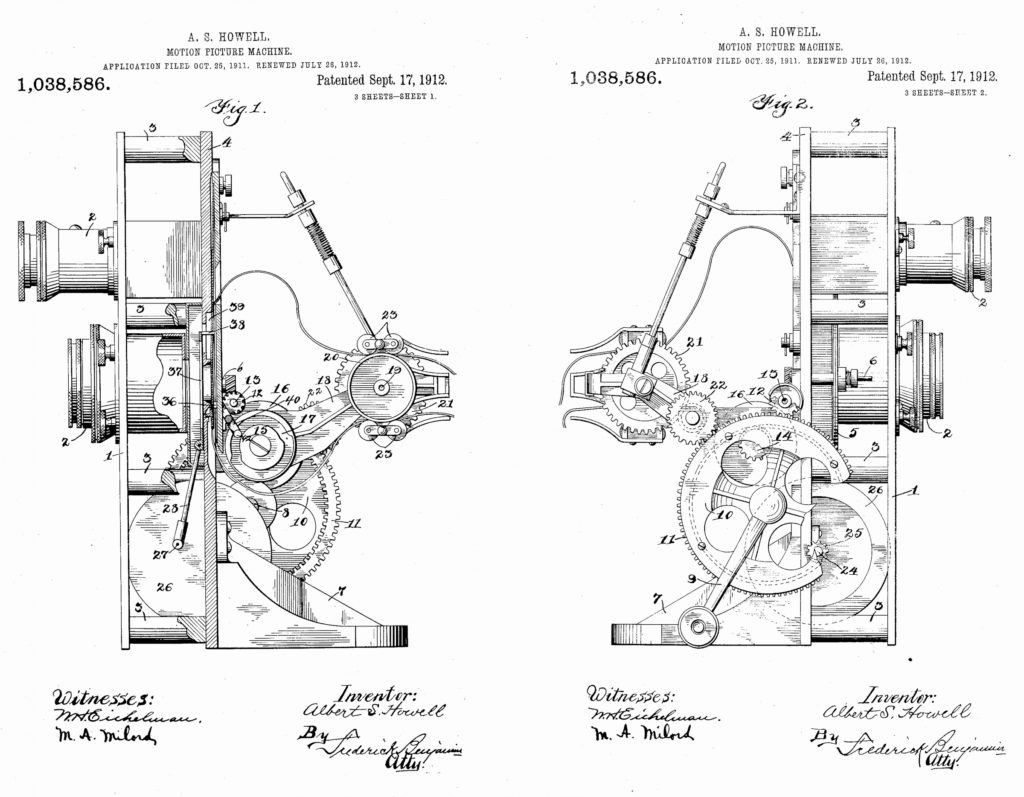

Shortly thereafter, photography came around, providing the almost-unthinkable ability to capture a moment on a light-sensitive piece of celluloid film. And by the 1890s, long lengths of this celluloid film could be quickly passed through the new motion picture camera, capturing fleeting frames of action that – when played back and projected with light at high speed – appeared to create a “moving picture” (or “movie” for short)! Surely, this had to be the end-all-be-all of innovation.

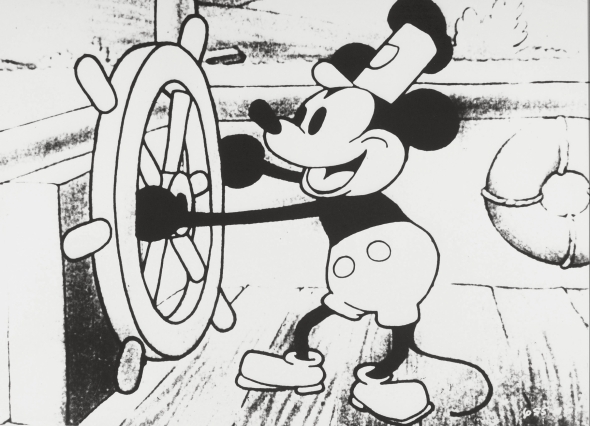

Next, the 1920s brought about the “talking picture” (including, unbelievably, the first cartoon to feature fully-synchronized, post-produced sound: Steamboat Willie). Progress now made moving pictures speak, too, but there couldn’t possibly be anything better.

And yet, in the 1930s, it was all about the wonderful world of color, as evidenced in Walt Disney’s groundbreaking 1937 film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs – the world’s first full-length animated feature film, shot with the brand new multi-plane camera. And audiences of the 1930s must’ve felt that they’d truly seen it all.

Until the 1940s introduced rudimentary stereoscopic 3-D! And they must’ve thought… well, you know the drill.

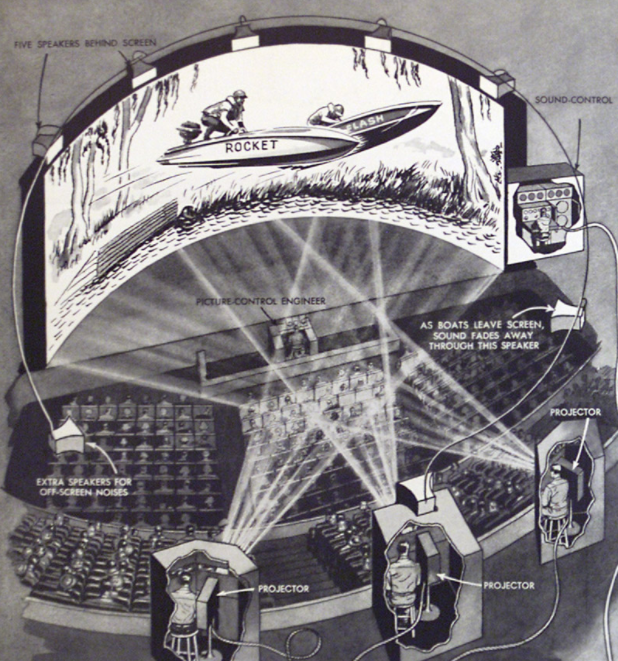

They were wrong. Things could get better. In the 1950s came Cinerama (a portmanteau of cinema and panorama) that had the audacity to do the unthinkable: take yet another step forward.

Now, three projectors could be synchronized to each display a piece of a motion picture on a curved, wraparound screen, and additional speakers to broadcast “off-screen” sounds… Unparalleled immersion created a newly dimensional experience for moviegoers.

And to audiences of the 1950s, it must’ve seemed that… well, you get the picture. Motion… sound… color… surround sound… panoramic picture! Like trying to see around a corner, it was simply inconceivable to imagine what the next breakthrough in filmmaking could be. But as always, one particularly inventive individual and his team were hard at work on that very question…

Eyes on tomorrow

If there’s one element of Walt Disney’s story that sweeps through all of our Lost Legends entries, it’s that – at his core – Walt was a futurist; an idealist; an optimist. Practically obsessed with the idea of progress and the hopes and fears it brought along with it, Walt dedicated much of his early career to finding new ways to infuse technology and innovation into animation, succeeding wildly as evidenced above.

And sure, we know that eventually Walt would shift his growing scientific thinking to big picture human advancement: high-efficiency mass transit, urban design, and what the communities of tomorrow would look like. But before any of that, Walt and his designers were determined to see the next step of filmmaking before anyone else. So what was the next step?

To their thinking, movies had already come alive with sound, color, and even 3-D. The next stage of cinema would have to be even smarter.

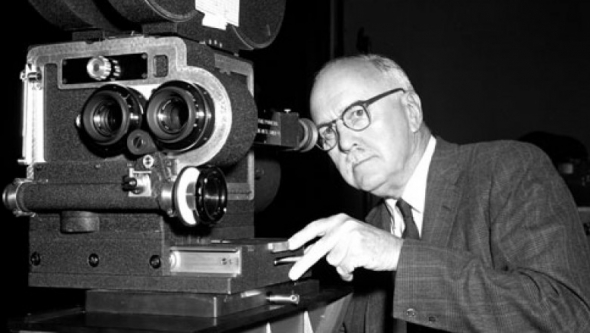

That’s when two prominent Disney Legends enter into the picture. The first was Ub Iwerks (Disney’s long-time animator, cartoonist, inventor, designer, and special effects guru) who’s credited with co-creating Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and his protégé, Mickey Mouse.

The second is Ub’s son, Don Iwerks. Young Don had joined Disney in 1950 working in a machine shop, but by 1954, he’d taken the reigns of a cameraman on Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

And now, the Iwerks and Disney would set to work on the next leap forward for film. And what could beat the curved screen of Cinerama?

Circarama

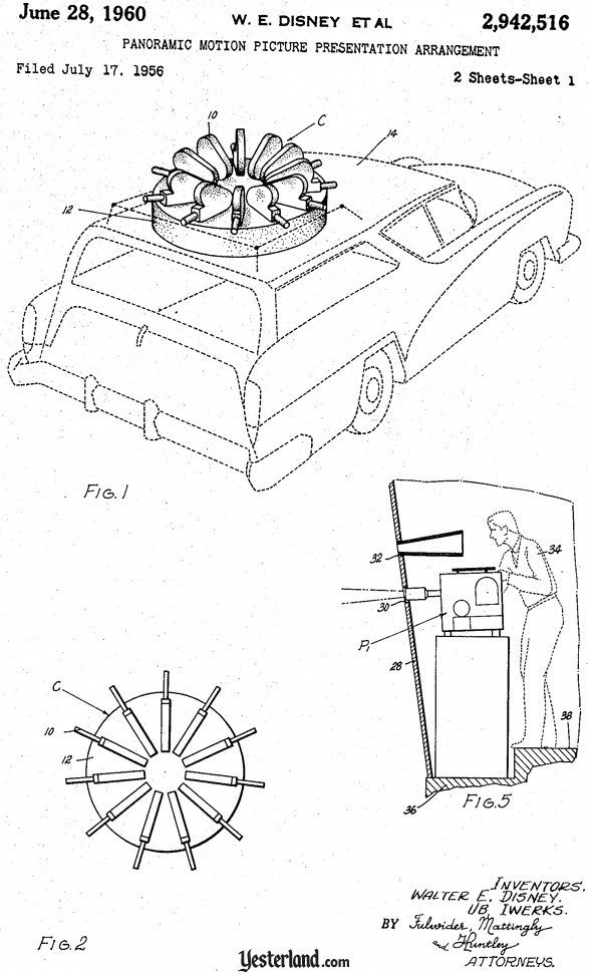

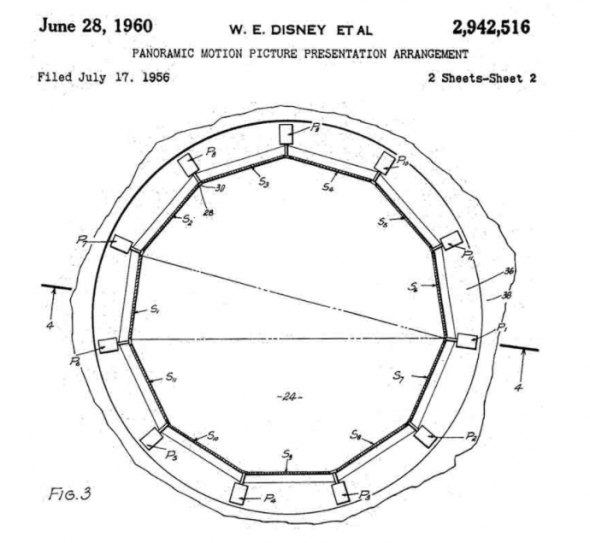

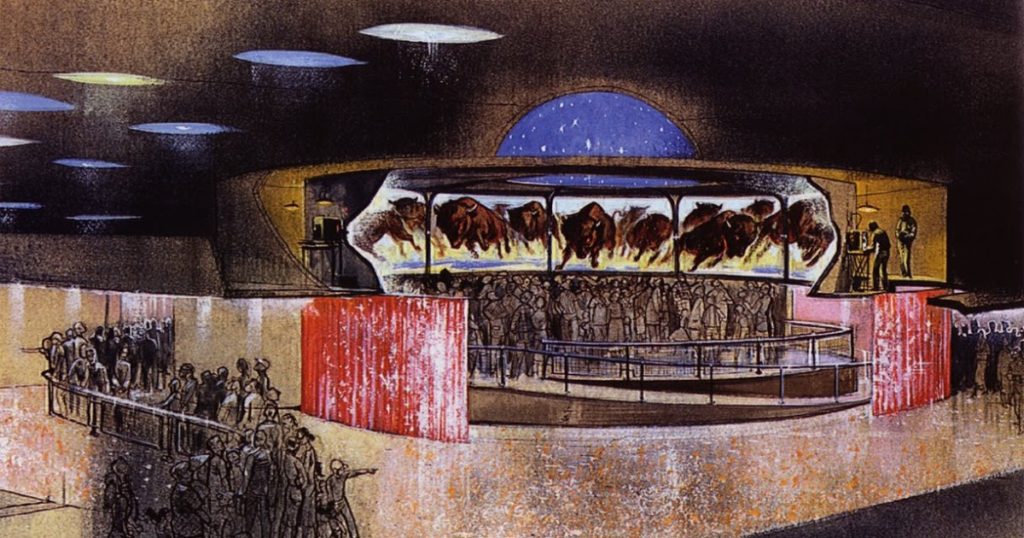

Picture it like this: filmmakers would take eleven motion picture cameras and arrange them in a circle, lenses pointed out. (See the actual, Passholder-exclusive photograph of the camera array, above.)

…Then, that circular array of cameras would be attached to the roof of a car as it drove through cities, forests, or deserts with all eleven cameras recording their own unique point-of-view of what surrounded the moving vehicle.

The eleven resulting reels of film could then be loaded into eleven projectors set around the circumference of a circular room, each pointed at a movie screen opposite.

When played in sync, the eleven “films” would appear to create a sort of continuous, 360° image, surrounding viewers standing in the room in an immersive picture, like wrap-around windows into another world… a sincere glimpse into the future of film. Which is lucky, because Disney needed any futuristic technology it could get its hands on…

When Disneyland’s Tomorrowland opened in 1955, it wasn’t at all what Walt had hoped it would be, since a tight budget and quick construction had left it little more than a showcase of corporate sponsorships. The good news is that the land’s main entry corridor – flanked by mirror-image showbuildings – would have a touch of Disney.

To quickly fill the south showbuilding, Walt had his filmmakers bring the sets of Disney’s 1954’s feature film 20,000 Leagues to Disneyland to put them on display as a sort of walkthrough.

The north showbuilding along Tomorrowland’s entry would be Circarama, hosting “A TOUR OF THE WEST” presented by American Motors: a picturesque travelogue of the American West and the natural splendors of the country’s unspoiled wilderness (though, more honestly, a tour of the deserts and landscapes within a few hours’ drive from Los Angeles… Disneyland’s opening was approaching fast, after all!)

Soon after Disneyland opened, Walt and company duplicated the Circarama technology and filmed a new Circarama presentation to act as a featured attraction for the United States pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. A New York Times article (sourced by our friends at Yesterland) reported:

“Innovations in photographic and movie projection methods will permit a 360-degree view of “the face of America” on a room-circling screen. The projection method, developed by Walt Disney, is known as ‘Circarama’. A color film, titled “America: The Land and The People,” showing a trip across the country, will be exhibited.”

In Belgium, Disney’s custom made Circarama travelouge, “America the Beautiful,” made its debut. Jerry Hulse of the Los Angeles Times noted, “…with the ending there is a loud applause… from persons of many countries… yes, even a few Russian visitors.”

Which is lucky, because the “America the Beautiful” Circarama film moved to the American National Exhibition in Moscow, Russia for a 1959 showing next.

But here’s where our story really picks up… On the next page, we’ll explore how Disney was determined to integrate this new, futuristic filmmaking into Disney Parks as never before, leading to one particularly brave installation: The Timekeeper. Read on…

i miss timekeeper it was awesome