theme [theem], n., a unifying idea; the deeper meaning; the thing that a story is about.

Once upon what feels like a very long time ago, each of Walt Disney World’s four theme parks was imbued with its own theme; a concise identity; a clear vision of what, exactly, it was about. Make no mistake, when Imagineers discuss “theme,” they don’t mean decoration, or props, or intellectual property; they mean an underlying, unifying idea; even a message. Theme with a capital-T, if you will.

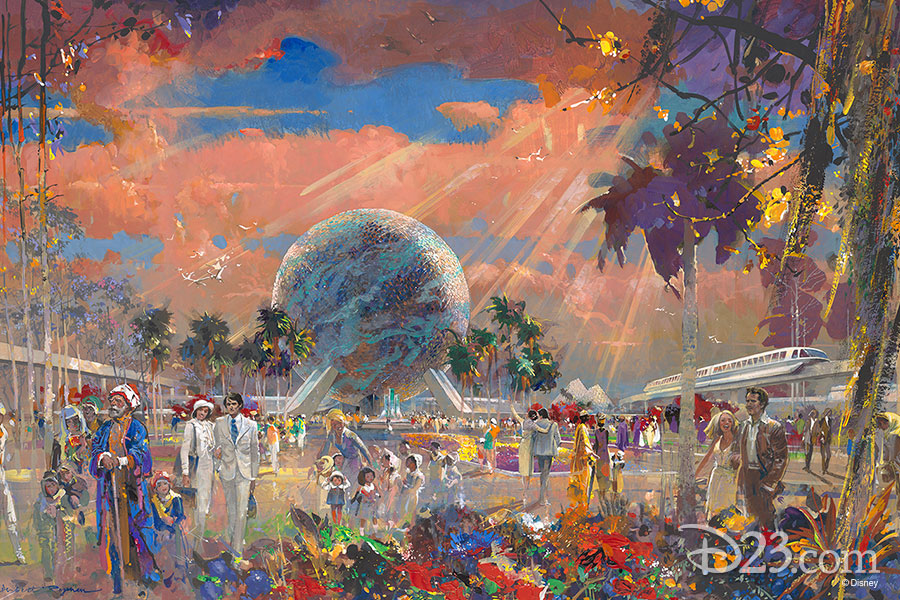

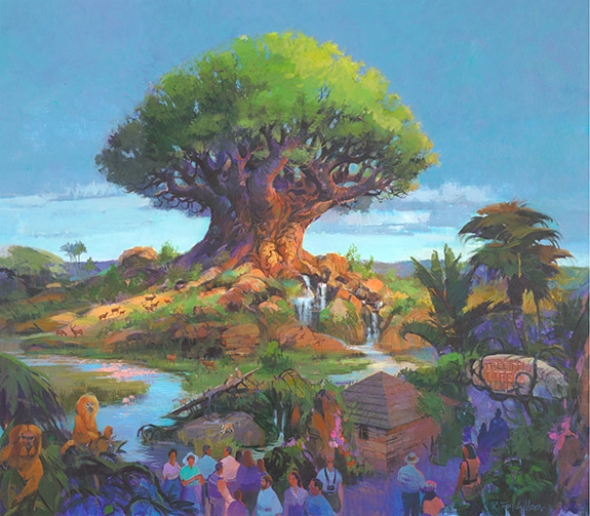

Consider the Theme underlying each of Disney’s parks at the time of its opening. Magic Kingdom was fantasy made real; EPCOT was reality made fantastic; The Disney-MGM Studios was about the romance and reality of Hollywood; Animal Kingdom, an embodiment of the supreme and untradeable value of nature. In the design and development of each park, each had an identity – one distinct from the others and wholly its own – that not only informed the attractions and environments within, but set a bar for, protected against, and served as stalwart gatekeeper to would-be interlopers.

It’s clear today that Walt Disney World’s four theme parks are four very different places built at four different times and with four different visions. (Few would stand in EPCOT believing they were in Animal Kingdom.) But beyond the decoration, are they really about four different things? Does each sum up to have something uniquely big – or for that matter, anything at all – to say? Or have Disney, Pixar, Marvel, and Star Wars created an era of interchangeable “Disney+ Parks” differentiated only by their decoration?

Together, let’s dig into Disney’s slow and steady homogenization of its U.S. theme parks, looking for evidence of their gradual meld into interchangeable identities.

Thematic overtures

If we’re looking for an inflection point – a specific time when Disney seems to have softened its commitment to parks’ themes and identities – we’d probably pin it around the New Millennium. After all, Disney’s two stateside New Millennium parks – Disney’s Animal Kingdom (1998) and Disney’s California Adventure (2001) – both committed to a centering philosophy or Theme… arguably to a fault.

When Animal Kingdom opened in 1998, Disney spent as much effort describing what the park wasn’t as what it was. The famous “Nahtazū” marketing campaign – stylizing “not-a-zoo” as a pan-African exclamation – sought to position the park’s animal collection as merely an aside to its adventurous spirit, authentic artistry, and anchor attractions (despite there being surprisingly few). A thoughtful triumph, Animal Kingdom was not an educational park per se – but one rife with messages for anyone who cared to look, and a number of pervasive themes shepherded and guarded by the park’s creative lead and patron saint, Joe Rohde.

In fact, while Disney’s Animal Kingdom was (and still is) celebrated for its incredible scale and Rohde’s deeply embedded themes (as explored and encapsulated in our Member-exclusive “Park Perspective” Special Feature), the park was also notorious for being too self-serious… even preachy. An intentional lightening of its message took place in the early 2000s, albeit never sacrificing its core themes and always keeping Disney characters and stories cast as cultural allusions encountered in the “real world” contexts of its lands.

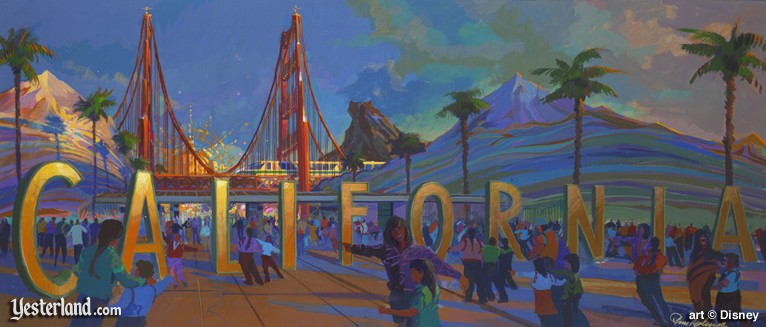

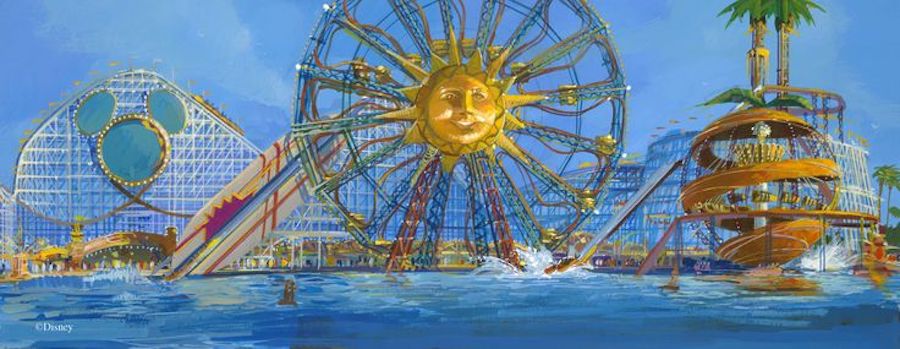

If Animal Kingdom was over-serious, then maybe the “MTV attitude” of Disney’s California Adventure was a direct response. As we explored in our three-part Disney’s California Adventure walkthrough, the park was underbuilt, underfunded, and creatively starved… but even its biggest critics wouldn’t have accused it of being thematically impure.

Just the opposite, the park was routinely criticized for being “too much California, not enough Disney.” Guests could scour each of the park’s 55 acres and find only the briefest cameo appearances by any recognizable characters.

California Adventure was positioned as an adult park; one focused on food, wine, and retail over frivolities like fantasy and romance at the old-fashioned Disneyland next door. Boardwalks, backlots, and bountiful farms abounded, each using its limited budget to convey something real about California in cartoonish, self-ribbing, two-dimensional terms.

Sure, Disney’s California Adventure read more as a Six Flags spoof of the Golden State than a complement to Disneyland’s earnest idealization. But its capital-T Theme might’ve been “California is a fun place to be with a lot of iconic things to see, do, and eat.” And whether or not you approved of the delivery of that Theme, it was pervasive.

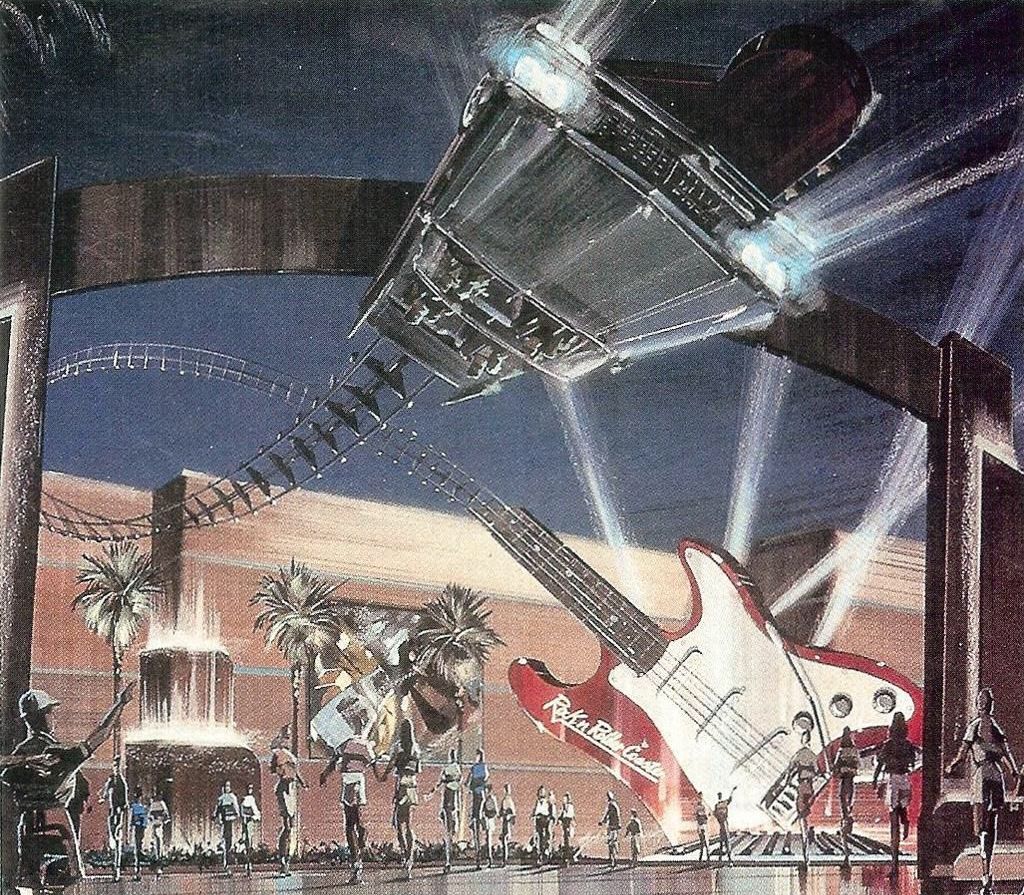

At the same time, mind you, Magic Kingdom was still highlighting its entirely-IP-free New Tomorrowland anchored by the Lost Legend: Alien Encounter (“fantasy made real”); EPCOT was in the midst of a rebranding as Disney World’s “discovery park,” dropping the lengthy “edutainment” dark rides of old and hinging on technological thrills – and still without characters, mind you (“reality made fantastic”); Hollywood Studios was still focused on movies, music, and television thrills with additions like Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster (operating on a new, post-Studio theme – maybe, “living the excitement of the movies, music, and TV.”)

So timeline-wise, we can pretty clearly see that around the New Millennium, each Disney Park was still at least fundamentally self-contained, each with a clear identity distinct from the others and a thesis (even an evolving one) all its own. Clearly, each park’s Theme was still serving as something of a “North Star”; a philosophical bar to entry that Imagineers sought to reach with any major addition to gain entry.

But of course, to fast-forward two decades is to find the parks in a very different state…

Fast forward

“At Disney, it’s not about an individual operating unit. It’s about the brand. First of all, the Disney brand. And then all those great franchises that fit underneath it. Look, we’ve got a wealth of riches. We’ve got an embarrassment of riches. And we don’t want to do anything that anyone else can do.

“A lot of times people say, well why don’t you do something – ? Why does everything have to be franchise oriented? Because that’s our barrier to entry. Because if any of our competitors had our intellectual property, guess what they would be doing? The exactly same thing that we’re doing. But they don’t have it. And we do.”

When then-Chairman of Disney Parks, Experiences, and Products Bob Chapek spoke to Theme Park Insider at the opening of the first of two Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge lands in 2019, the executive’s characteristically brusk explanation pretty concisely summed up what had happened to the positioning of Disney’s theme parks within the company.

Appropriately, so did Galaxy’s Edge. Positioned as a peak of modern Imagineering, here, on paper, resided Disney’s long-sought “answer” to the Wizarding World of Harry Potter that had premiered at Universal Orlando nearly a decade earlier. Taking all that Disney had learned from its Hogsmeade-spurred entries into the “Living Land” genre (Cars Land, New Fantasyland, Toy Story Land, Pandora: The World of Avatar), Galaxy’s Edge was meant to represent the very height of the field and its 21st century lean into immersive, cinematic, single-IP lands.

Incarnate as the distant, Outer Rim planet of Batuu and its Black Spire Outpost village, Galaxy’s Edge whisked guests away into an ultra-immersive world – one layered in lore and set on a perpetually-recurring, specific date in the Star Wars universe (between the Disney-produced “sequel trilogy” entries The Last Jedi and The Rise of Skywalker).

In so doing, Disney (in)famously committed to a Star Wars themed land… that neither Han Solo, Darth Vader, nor Yoda could ever canonically inhabit. Practically obsessed with adherence to canon-approved timelines and fixated on in-universe world-building even at the expense of courtesy (“Where are the what? Bathrooms? Hmm… Oh, could you mean, refreshers?” “Fireworks? Never heard of ’em.”), Galaxy’s Edge was, in some ways, a project so committed to its own seriousness and superiority, it was hard to believe it was given the green light.

About the only thing bigger than Galaxy’s Edge’s conceptual footprint was its physical one. Wrapped in an envelope of alien rock walls and spires giving Cars Land a run for its money; filled with bauble shops and vendor carts recalling Diagon Alley; sprawling, all-consuming, and immersive as only Pandora had been; anchored by one of the most elaborate (and expensive) rides ever produced by Walt Disney Imagineering; encouraging guests to live their own Star Wars adventure… This was meant to be a magnum opus; a landmark of every advance that had been made in the pivotal two decades preceding.

And as much as Disney historians or fans might’ve resisted, the characteristically brusk Chapek’s frosty delivery made the point no less valid. If any of Disney’s competitors had Star Wars, what would they be doing with it? As the soon-to-be(-then-not-to-be) CEO gestured at the $1 billion, 14-acre land devoted to one of the most enduring pop culture franchises of all time, it would’ve been difficult to imagine that if those anonymous competitors had Star Wars, they would do anything other than to use it – and almost certainly, not at expertly as Disney Imagineers had.

Despite the context, though, neither fans’ nudging questions nor Chapek’s chilly response had really been about Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge. Instead, both parties were speaking to a larger unease, simmering online and in Disney’s own evaluation metrics for the better part of two decades: that somewhere along the line, Imagineering’s most ardent fans and the executives who oversee it had developed two very different answers to one very essential question…

What are Disney Parks for?