From hubs to FastPass, “DVC” to Dole Whips, “Disney Parks” is a language all its own. Do I wear a MagicBand, or listen to it? While the answer might seem obvious to you, frequent visitors to Walt Disney World and Disneyland might not even realize just how many invented words, phrases, and abbreviations have made their way into their every day vocabulary!

Park Lore’s collection of frequently-used (and frequently-misunderstood) terms is meant to be a one-stop-shop for “jargon” you might see around the site. It’s also one of over a hundred Extra Features in Park Lore’s Vault of Member-exclusives. Obviously this one’s open to all, but if you’re enjoying your time on the site, consider becoming a Member for as little as $2 / month to unlock all over a hundred Extra Features, reveal hundreds of pieces of rare concept art across the site, gain Member-exclusive benefits, and support this ad-free, clickbait-free storytelling project.

The attractions at Disney Parks represent – in many cases – some of the most sophisticated technology on Earth to be used for entertainment. So it’s unavoidable that attractions are bound to unexpectedly fail to perform for a few minutes, hours, or days. When a ride is closed due to technical difficulties, internal speak notes that the attraction is “101,” or not operating. A radio call that an attraction is “104” is good news for guests who choose to wait out the closure – it means the ride is re-opening. “102” signals that a ride is operating as expected, in full show mode.

Many Walt Disney World visitors are more familiar with ADRs – advanced dining reservations – than they’d like to be. Increasingly, fans note that if you choose not to make ADRs as soon as you’re able (6:00 AM EST 180 days out), you might as well assume you’ll only be dining at “quick-service” spots during your trip.

It’s not only that Walt Disney World’s “table-service” restaurants are in high-demand… it’s that – unlike many full-service restaurants – Walt Disney World’s finer dining options do not set any tables aside for walk-ups. While a last-minute cancelation may grant you a table, Disney is content having every single seat pre-booked 6 months out, meaning ADRs are your best chance to dine well.

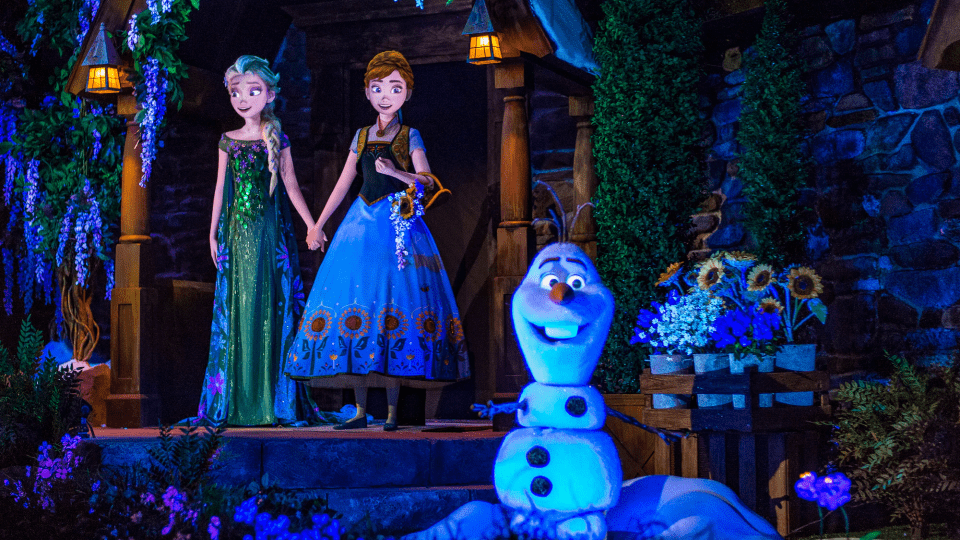

Formally trademarked in 1964 and registered in ’67, Audio-Animatronics is the name given to three-dimensional animated figures created by Walt Disney Imagineering. Literally a fusion of audio, animation, and electronics, Walt’s early designers oversaw the invention of the spectacular technology (first debuted in the Modern Marvel: The Enchanted Tiki Room, where you’ll find our full story on the showstoppers’ origins.)

Though our must-read list of the 25 Best Animatronics on Earth includes robotic figures from around the globe, technically, patented-and-trademarked “Audio-Animatronics” are exclusive to Disney Parks and Resorts.

You can learn more about Audio-Animatronics in our Extra Features exploring Animatronics in attraction queues and outside of rides altogether. See “B-mode” for more.

Given the sophistication that goes into creating Audio-Animatronics and their typical twelve-hour workdays without a break, it should come as no surprise that sometimes, an Audio-Animatronic or show scene isn’t fully operational. In Walt’s time, a malfunctioning Auctioneer in Pirates of the Caribbean called for the ride to go “101” until the show was fixed. Today, the standards are a bit different. Particularly in the technologically trickiest rides, encountering a figure or moment in its “B-mode” isn’t even so unusual, and generally, most guests probably don’t even recognize there’s anything amiss.

For example, on Na’vi River Journey at Disney’s Animal Kingdom, the ultra-advanced A-100 figure that serves as the ride’s culmination (and likewise rests pretty high atop our list of the 25 Best Animatronics on Earth) occasionally disappears from guest view and is replaced with filmed footage of the Shaman of Songs where she once sat.

In Star Wars Rise of the Resistance, a malfunctioning Kylo Ren doesn’t shut down the highly-sought-after ride; instead, the whole scene shifts to a “B-mode” presentation outside of the nearby “windows,” requiring a slightly alternate program for the ride’s vehicles. Hopper will appear in “It’s Tough to be a Bug” even if it’s on-screen. While the final full-body carnotaur is being repaired on the Modern Marvel: DINOSAUR, a head-on-a-stick on the left takes its place.

Perhaps the most famous “B-mode” on Earth is one that’s essentially become one particular figure’s new “A-mode.” As told in our list of Frozen, Flaming, and Malfunctioning Animatronics, the infamous Yeti inside the Modern Marvel: Expedition Everest has been stuck on its “B-mode” since just a few months after the ride opened. Frozen in place with its hand outstretched to its farthest reach, fans blow on the creature’s fur as strobe lights help give the illusion of movement. Like all scenes in B-mode, the effect more or less works, so most riders don’t even notice they’ve missed something!

Walt Disney’s initial land purchase in Anaheim totaled just 160 acres (with Disneyland itself occupying only 60) among orange and strawberry fields. Nestled into existing streets and the under-construction I-4, the park may have staked out its spot in Anaheim before the urban sprawl of Southern California caught up to it, but its isolation wouldn’t last. Even if Walt could never have imagined the extent of urbanization along today’s Harbor Blvd., he did recognize the need to somehow insulate Disneyland from the real world.

Thankfully, Disneyland is shielded from the outside world by way of a berm, literally a raised, earthen mound encircling the park and planted with trees. Today, it’s practically impossible to spot any feature of the “real” world once you’ve passed into California’s Main Street. Only the Monorail (which runs along Harbor Blvd.) and the Main Street Train Station provide views out of the park. Both Toontown and Galaxy’s Edge are physically outside of it and accessed through tunnels, but are shielded from the outside world by their own berms: the Toontown hills and the spires of Batuu.

Since Magic Kingdom was set among the (Disney-owned) wilderness of Central Florida, it was built without a berm at all. Unfortunately, so was Disney California Adventure, from which guests can sometimes spot external hotels or power lines. The park’s lack of a berm is one of those “can’t-quite-put-your-finger-on-it” issues that frustrated Imagineers fans.

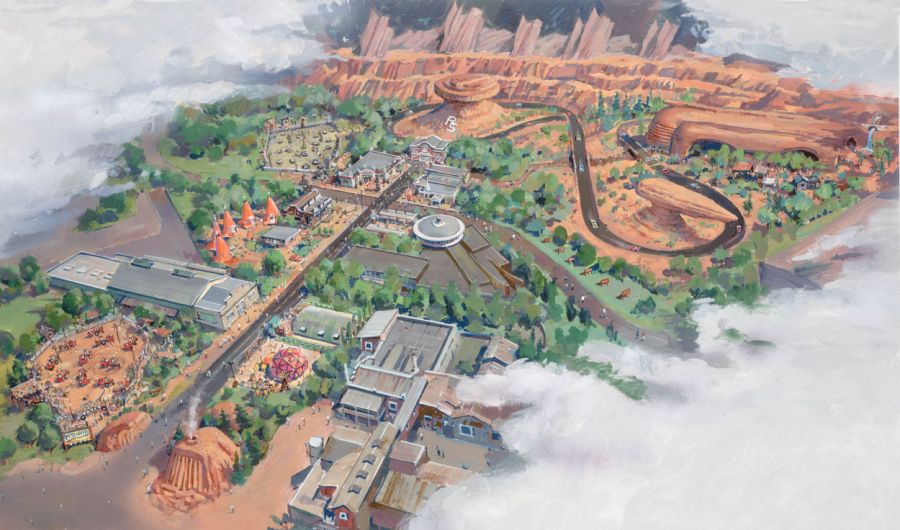

In modern Imagineering, designers have sometimes gotten serious about berms. The Cadillac Range of Cars Land may be the most all-encompassing purpose-built “berm” out there, insulating the land from views of Katella Ave. (even if it gave hotels there a pretty undesirable view). Disneyland Paris was so lovingly (and expensively) developed, each land is contained within its own thematic berm. DisneySea’s “berm” is an aquatic one, making the park’s waterway to appear to connect to Tokyo Bay. Galaxy’s Edge in Florida was built with an artificial raised berm of its own, disguising views from within.

So while berm doesn’t exclusively mean “a raised, earthen mound planted with trees” anymore, the principle of shielding guests’ views from the outside world remains as strong as ever.

One of Disney’s most clever contributions to the fields of design and themed entertainment is the idea of the “Blue Sky” phase of design. In theory, the “Blue Sky” phase is when artists, storywriters, and creators are encouraged to dream big; when the sky’s the limit. You might consider it a “yes and” phase of design. Sure, eventually, ideas will need pared down and brought within the limits of time, budget, and technology. But when the “Blue Sky” phase is done right, it’s a chance to idea generate without limitations, and sometimes that’s where the best ideas come from.

Chances are that none of our Seven Modern Wonders of the Theme Park World would ever have come about if designers skipped the “Blue Sky” conversations and instead just stuck to what already existed.

In our discussions about Imagineer-created worlds and expanded mythologies, the idea of “canon” comes up a lot. That’s because “canon” is typically a really big deal. By definition, canon is an official recognized set of sacred texts. In practice, canon is essentially the material accepted as officially part of the story in an individual universe of that story. For something to be “canon” means that it’s been elevated to be “official.”

For example, Star Wars has thousands and thousands of officially-sanctioned comic books, novels, and television episodes, but an overwhelming majority exist as part of the “Expanded Universe,” outside the realm of official canon. For example, there’s signficant debate about whether or not the Lost Legend: STAR TOURS is part of the Star Wars canon. Do the events and encounters we have on the ride actually reside somewhere on the official and highly-academic Star Wars timeline?

Only select works are part of the canon. As it happens, Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge is one of them. That means that Batuu – and the characters, events, and experiences guests have there – are as “real” as anything seen on screen… the happenings there even impact the events of Episode IX. Being part of the canon is a huge honor… but also brings serious responsibility. Theoretically, selling Grogu plush or having Darth Vader walk around on Batuu would be a hugely anachronistic move that would mess up the land’s officiality.

Compare that to Avengers Campus, where heroes long-dead in the Marvel Cinematic Universe happily reside alongside heroes introduced after their deaths! Obviously, the events and encounters that take place in Avengers Campus aren’t “canon” to the MCU. They don’t fit anywhere specific on the timeline, and anything that happens is something tangential to the main series. In fact, the land officially takes place in a spur timeline.

This is a term you’ll quickly pick up even if you’ve only been to Disney Parks once or twice.

Walt Disney had a few famously groundbreaking ideas when it came to Disneyland (like its exclusion of alcohol, for example… oops), but one of the most famous was his theatrical terminology. Walt decreed that when Guests (not customers) stepped into his “worlds of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy,” they would be stepping into a show. Fittingly, anyone who was a part of that show – from the CEO to a sweeper – was, to a Guest, a Cast Member, playing a role in their story.

That also played into the strict rules Walt had about what could be seen “on-stage” versus “backstage,” helping to flesh out the illusion of an insulated park protected from the outside world. That theatrical mindset was taken even further in subsequent parks, with Magic Kingdom going so far as to provide the “Utilidor” corridors beneath the park so Cast Members can travel discreetly between different lands without shattering any illusions.

Combine sugar, nerves, and exhaustion; mix with swirling, twisting, spinning rides; set to high Floridian heat… This is a classic recipe known all too well to Cast Members: the “protein spill.” Like it or not, vomit is more than a daily occurrence at each Disney Park. As you’d expect, Cast Members always treat guests with dignity and respect in such vulnerable, embarrassing, and potentially-scarring moments, finding First Aid as necessary. Meanwhile, a quick call of “Code V” signals that a clean-up is needed. You can imagine what “Code P” and “Code U” are for. “Code H” has to do with the Main Street horses, and we’ll leave it at that.

All rides and shows are equipped with E-Stops (short for Emergency Stops) that will halt the attraction safely. E-Stops can be initiated for any number of reasons, as serious as an Earthquake or power outage to as simple as a hat falling onto a ride’s path.

Of course, all rides are equipped with countless sensors, cameras, and other redundant safety features to ensure that guests (and the attractions themselves) are safe, so experiencing an E-Stop isn’t even that rare…. Most guests to a Disney Park have probably been on a ride that’s unexpectedly stopped for a moment. In some cases, the house-lights may even turn on as a Cast Member makes an announcement. And if the situation requires it, an E-Stop might even trigger an evacuation. See “in-show exit.”

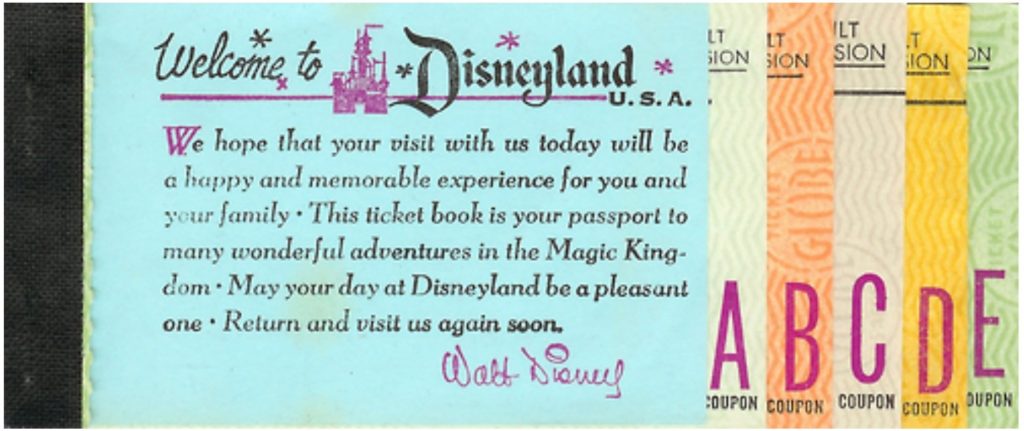

Long before “e-” meant electronic, E-Tickets were still a big part of the Disney experience.

In 1955, admission to Disneyland cost $1.00.

But of course, it’s not quite that simple. Though Disneyland’s single entrance and its charged admission fee were revolutionary, the park also had a feature that very closely resembled other amusement parks and boardwalks of the early 20th century: a pay-per-ride system. In its earliest years, some attractions (like the 20,000 Leagues exhibit or King Arthur Carousel) required 10-cent A-Tickets, while the most exciting (think Jungle Cruise) needed the 35-cent C-Ticket. An 8-ticket booklet cost $2.25 on top of admission.

The year after opening, Disney reevaluated its rankings, creating the D-Ticket. In 1959, the largest expansion in the park’s history saw the opening of three brand new, headlining rides at once: the Matterhorn Bobsleds, Submarine Voyage, and the Disneyland-ALWEG Monorail. All three were so grand, a new designation was created for them, requiring the most expensive and limited ride voucher yet: the E-Ticket.

Disney officially switched to “pay-one-price” admission in 1982. Even though it’s been almost 40 years since the last “E-Ticket” coupon was exchanged for a ride on Big Thunder Mountain, the term “E-Ticket” is still used to describe Disney’s highest-caliber rides; anchor attractions that headline new expansions or use cutting-edge technology. In fact, we created our own list of each park’s modern E-Ticket count, to surprising results!

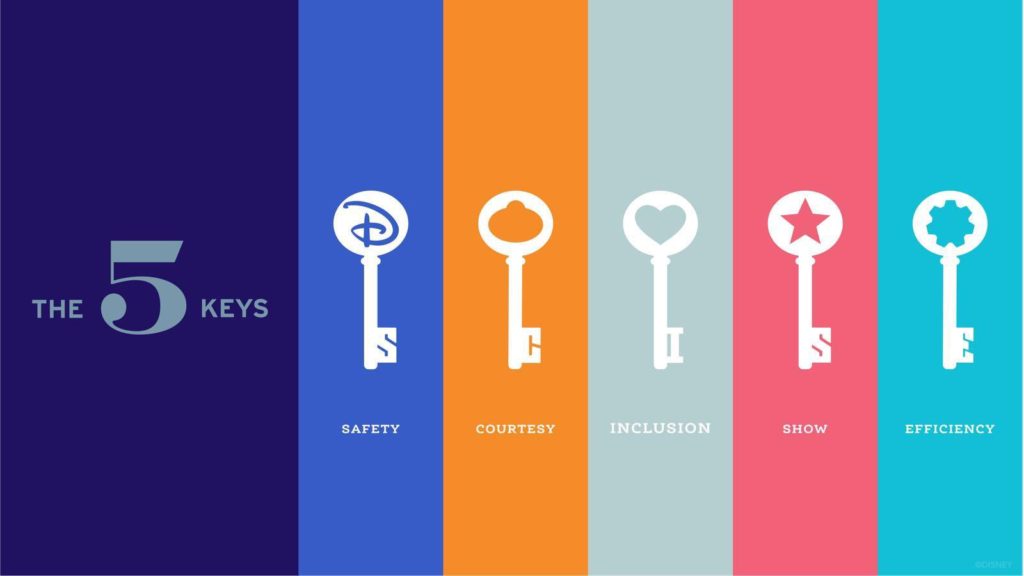

For decades, The Walt Disney Company’s legendary guest service strategy has been shaped by an internally-crafted set of guiding principles called the Four Keys: Safety, Courtesy, Show, and Efficiency. Those four “basics” have remained the building blocks of Disney’s internal trainings for new Cast Members and for Disney’s outward-facing Disney Institute. As a result, thousands of companies across the globe have “adopted” the Four Keys as a blueprint for decisions of their own.

Safety, Courtesy, Show, and Efficiency are in a very intentional order. For example, on paper, it’s more important for Disney Cast Members to maintain the “Show” than to worry about “Capacity.” Likewise, it’s okay to suspend the “Show” when “Courtesy” is at stake (like, for example, a 1930s explorer at Indiana Jones Adventure handing you a FastPass when the ride breaks down). And of course, “Safety” tops it all, meaning it’s okay to suspend Efficiency, Show, and even Courtesy in a matter of Safety.

In 2020, Disney made the spectacular and surprise announcement that they had decided to add a Fifth Key, Inclusion. Disney’s commitment to a sense of belonging, accessibility, and respect for culture and custom goes well beyond mere “Courtesy.” Inclusion is something that’s both inwardly-directed and outward. For example, it’s why Disney’s annual release of “coincidental rainbow” merch is now an official line of Pride merchandise, with Ear Hats sporting the flag patterns of the LGBTQIA+ community!

As of 2021, one of the most visible, everyday examples of the Inclusion Key in action was Disney’s restructuring of its famously restrictive Look standards, finally allowing Cast Members to sport piercings and tattoos while eliminating strictly gendered rules for nail polish, hairstyles, costumes, and other cultural embellishments. Cynics no doubt suggest that the move is at best overdue, and at worst an attempt to restock the dwindling pool of employees available to the parks (in an era where most twenty-somethings and thirty-somethings have tattoos or piercings, and want to work for companies whose beliefs align with their own).

Sure, it’s a lofty “North Star” to strive toward, and neither The Walt Disney Company as a whole nor the Parks, Experiences, and Products segment will always get it right, but at least the company’s focused commitment toward it exists… and the ramifications of Disney including “Inclusion” will no doubt ripple to those thousands and thousands of organizations that model their own guiding principles on Disney’s, or learn them from the Disney Institute.

When Disney Parks enthusiasts talk about a “gate,” they usually don’t mean entrance turnstiles. Often, “gate” is a synonym for theme park. Simple enough, except when fans begin talking about “Walt Disney World’s cinematic gate” (Disney’s Hollywood Studios) or “Disneyland’s second gate” (California Adventure), essentially turning the name game into a pop quiz on association or Disney Parks history.

When will Disney World add the legendary and mythological “fifth gate?” It’s anyone’s guess.

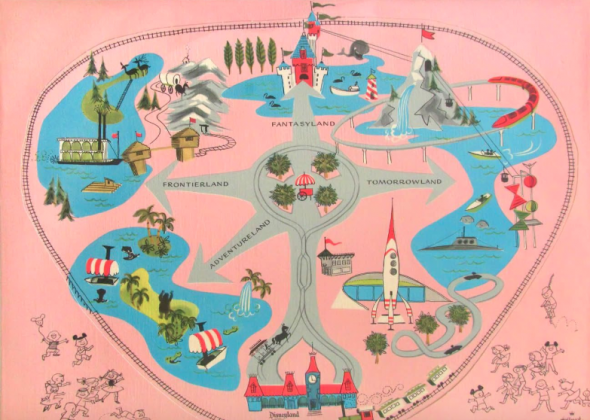

Have we mentioned yet that Disneyland was revolutionary? Just as its single entrance and its admission fee were radical, so was what followed: how that long, single, shared entry forced all guests into the center of the park. But this, too, was intentional and groundbreaking. While other amusement parks had developed as long, stretched midways or piers lined with attractions, Disneyland was built all-at-once in what designers called a “hub-and-spokes” layout.

You can see why – when viewed from above, the park is laid out like a wheel or a bicycle tire. Main Street forces all guests to the center of the wheel, with themed lands branching off via pathways laid out like spokes on a tire. From that center point, guests are “pulsed” into the lands, able to circumnavigate the park however they’d like. What’s better, the hub-and-spokes layout ensures that guests are never too far from anything – even the opposite ends of the park are connected via a path through the Hub! – and that wayfinding is simple and natural: just get back to the castle!

Obviously, Disney’s “castle” parks and Animal Kingdom are the best examples of the hub-and-spokes layout, with subsequent parks using figure-8 (California Adventure, DisneySea, and Epcot) and… y’know… an utter, unplanned, horrible collection of dead-ends (Disney’s Hollywood Studios), but the hub-and-spokes layout is still used in urban planning and design and is recognized as one of the great innovations of Disneyland as a functional place.

See, “WDI”

Most times when a ride E-Stops, it’s only a momentary interruption before the attraction resumes operation. Even when a show can’t resume in its optimal show condition, it’s often easiest to simply cycle through the ride vehicles and have guests disembark at the station, with a FastPass to return later. What happens if your ride E-Stops and Cast Members determine it can’t be continued? As its name suggests, an “in-show exit” is Disney’s friendly wording for what the less-thoughtful would call an evacuation.

Certainly, most in-show exits aren’t emergencies. But if it’s determined that maintenence or a hard reset will be required before an attraction can continue or if it’s unknown how long a problem might persist, Cast Members will visit each ride vehicle, manually release guests, and escort them to the nearest exit in an expectedly orderly fashion.

As you can imagine, many industry fans have their wish list of rides they’d love to have an in-show exit while riding (who wouldn’t want to walk through Disney’s epic dark ride scenes, or come within feet of a frozen, malfunctioning Audio-Animatronic?). Like all things, Disney’s got the in-show exit down to a science, so even if it requires stepping off of a boat or a seemingly-perilous trip down stairs, such evacuations are really quite simple with all the right hardware to make it as easy as possible for guests.

It’s hard to be a part of Disney Parks fandom today without seeing debate and discussion around IP – intellectual property. IP is a legal area meant to protect intangible things like trademarks, patents, and copyrights. At least for now, U.S. Intellectual Property legislation protects Mickey Mouse, for example, as an image and likeness usable only by the Walt Disney Company (an incredibly controversial protection which is near expiration…).

Disney has perhaps the most extensive, recognizable, and valuable portfolio of IP on Earth. Look at Mickey and Friends alone! Then think of how Disney took public domain fairy tales (like Snow White, The Little Mermaid, The Snow Queen, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and Sleeping Beauty) and created the definitive (and very, very protected) versions. Then add in recently-acquired IP (Marvel, Star Wars, Pixar, Indiana Jones) and you can see why Disney’s intangible brand is said to be worth $40 billion.

Naturally, IP and its place in Disney Parks is the hot topic of today. While Walt himself stocked Disneyland with the IP that mattered to audiences of the 1950s, the concept was thrown into overdrive during Michael Eisner’s cinematic tenure in the ’80s and ’90s and has been increased exponentially by CEOs Bob Iger and Bob Chapek. That’s why fans mourn that the era of original concepts appears to be over (Disney World’s last major, non-IP attraction was Expedition Everest in 2006) with any and all known future projects tied to box-office blockbusters or heavy-hitting brands.

As evidenced by Adventureland, Fantasyland, Tomorrowland et al, the notion of “lands” being smaller, separated, focused areas within a larger, themed park began with Disneyland. There have been some purposeful renamings. EPCOT Center opened with two “realms”; California Adventure with four “districts”; Walt Disney Studios with four “lots”; Islands of Adventure with six “islands”; but ultimately, industry fans still know them all as permutations of “lands.”

“Lands” is one of those words theme park fans toss around in conversation as if their friends understand, but for most of the “general public,” it’s just jargon that doesn’t really mean much. It’s clear that even fifty years after Disneyland, the use of the term didn’t pass muster with major media publications, which largely referred to the Wizarding World of Harry Potter as “a Harry Potter theme park” at worst, and “a theme park within a theme park” at best.

Probably because the industry shifted to immersive, self-contained, IP-focused lands following Potter’s lead, “land” has become a bit more standard and understood. The country’s next immersive land wasn’t called Radiator Springs, but Cars Land. Don’t forget Toy Story Land, “a bug’s land,” Hollywood Land… Before it was titled, even mainstream media described Galaxy’s Edge as a “Star Wars land.” Heck, SeaWorld Orlando even named their immersive recreation of Sesame Street (which is already a recognizable place name!) Sesame Street Land! So maybe after 65 years, “land” is finally a word that even the general public associates with a smaller, separated, focused area within a larger, themed park!

At the 2017 D23 Expo, Disney dropped a surprise announcement: Disney California Adventure’s Paradise Pier was going to be reimagined into the brand-friendly Pixar Pier. More than just the next step in the Pixarification of Disney Parks, the announcement introduced a new word in the Disney Parks lexicon: neighborhoods. It’s Disney’s new way of describing (or maybe, explaining away) smaller – usually juxtaposed and unrelated – areas within a larger “land.” And frankly, how else would you describe a mid-century modern Incredibles area being next to a Toy Story inspired area filled with oversized toys, all in one “land”? That’s just the “neighborhoods” of Pixar Pier!

The “neighborhoods” concept might’ve been a one-off, except that Disney used the same convention to make sense of the ongoing reimagining of Epcot, where the former Future World is being arbitrarily subdivided into the “neighborhoods” of World Nature, World Celebration, and World Discovery.

Between the two applications, Imagineering fans have learned to be a little leery about Disney dropping the term “neighborhood” in any announcement, because at least so far, it’s associated with thematic cop-outs of Pixar Pier and arbitrary redistricting of Future World.

Though it’s become deeply embedded in industry fans’ vocabulary, your average Joe probably wouldn’t have a clue what you meant if you mentioned a “nighttime spectacular.” Of course, that’s the term applied to grand, show-stopping, final productions put on nightly at most Disney Parks. Reserved only for top tier entertainment, “simple” projection displays (like the gorgeous Tree of Life Awakenings or the Chinese Theater projection shows) rarely qualify; in fact, most fans wouldn’t count awesome nighttime parades like Paint the Night or even fireworks shows in this exclusive category.

Rather, think on the scale of Disneyland’s Modern Marvel: Fantasmic!, Epcot’s Illuminations, or California Adventure’s World of Color – each truly sensational, memorable in every way, and a perfect capstone to a day at the park. Another common giveaway that you’ve found a nighttime spectacular is that guests either have to get a ticket or queue up hours in advance to secure the best spot. The benefit for Disney? A nighttime spectacular keeps guests lingering in the park for dinner and shopping when they might otherwise have chosen to head back to the hotel in the early evening.

Nighttime spectaculars are the reason that Disney Parks fans are known to visit their city’s Independence Day fireworks and let out a resounding, “Meh.”

Designed by Roger Broggie and Bert Brundage and memorably named by Bob Gurr, the Omnimover is a Disney-patented ride system developed initially for use in the Lost Legend: Adventure Thru Inner Space. Made of a continuous chain of clamshell-shaped vehicles, the Omnimover is wildly high capacity since it moves constantly… even during loading. Plus, each cab can rotate along the ride’s course, famously giving designers the in-attraction power of a camera by focusing guests’ attention in precisely the directly they want.

Variations of the ride system abound from The Little Mermaid: Ariel’s Undersea Adventure (which took the “clam” shape literally) or Epcot’s Lost Legends: Journey into Imagination, Horizons, World of Motion, The Living Seas, and Spaceship Earth (which each use modified or redesigned variations). The most famous application, bar none, is in the Haunted Mansion where the vehicles are cast as the iconic “Doom Buggies.” That’s one reason the Omnimover made our list of the Seven Modern Wonders of the Theme Park World.

Like all great ride systems, other manufacturers have since created “Endless transit systems” of their own. In fact, Disney purchased Vekoma’s version for the Modern Marvel: Phantom Manor! But Disney’s 1968 patent still makes the definitive version their own.

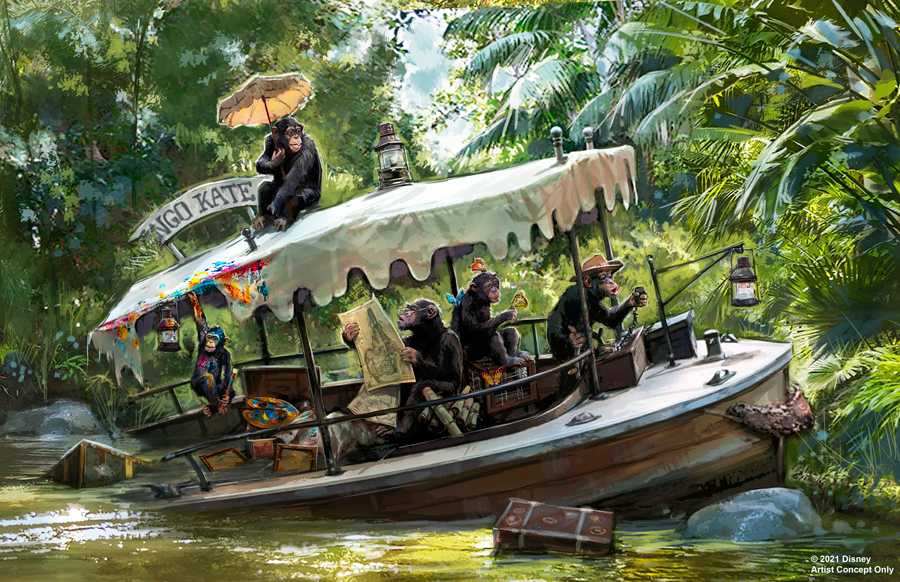

As the story goes, soon after the opening of Disneyland, Walt overheard a guest say they’d like to skip the Jungle Cruise, as they’d already been on it last time they visited. Disturbed by the notion, he went to his design team and gave them a simple mission: “plus it.” What he meant was that designers need to revisit attractions – even classics! – and improve them in big and small ways. The Elephant Bathing Pool, crumbling temple, and the “trapped safari” were the result!

Wonderfully, the idea of “plussing” has become one of the most enduring elements of Disney Parks: their adaptability and continuous enhancement. In so doing, Disney returns even to its most treasured classics and adds a little more magic by way of enhanced special effects, projection technology, refreshed music, updated Audio-Animatronics, “throwbacks” for fans, and more. “Plussing” has become a signature different of Disney, and it’s all in the tradition of Walt wanting to keep things moving forward to impress his Guests.

The latest generation of “plussings” is perhaps the most important. After years of piecemeal fixes that some attributed to “political correctness,” Disney decided to get serious about inclusivity (see, “Five Keys”) and reportedly formed an Imagineering committee with the express job of ensuring Disney Parks don’t include harmful stereotypes (even in jest) and that everyone feels at home within. Naturally, that’s meant some significant modifications to a park built in and based on pop culture from the 1950s, but it’s all in the name of keeping Disney Parks timeless, thoughtful, inviting, and fresh.

Though “it’s a small world” might not seem to have much in common with Mission: SPACE, they share one fundamental thing: the kind of building they’re housed within. Showbuilding is “Disney speak” for something relatively simple: a soundstage, just as you might find on a studio backlot. Showbuildings give Disney Imagineers complete environmental and atmospheric control, allowing them to create ancient temples, moonlit Caribbean towns, the Hundred Acre Woods, and even the vastness of outer space.

It’s impressive enough that Disney parks are littered with massive, gargantuan, enormous showbuildings that contain their biggest rides; what’s even cooler is that most guests never, ever see them. Spectacularly concealed, 16 of the Biggest Showbuildings in Disney Parks absolutely amazed us… you’d never guess that only 5% of the Haunted Mansion actually takes place in that stately, mysterious manor itself…

A term invented during the design of the Modern Marvel: The Amazing Adventures of Spider-Man, “squinching” is the animation technique used to instill artificial perspective in a 3D scene viewed from a moving vantage point. It sounds complex, but in theory, it makes sense – if you were to look down a hallway and lean to the left and right, your view down that hallway would change, even if only slightly.

So to make guests feel that they’re riding past a hallway projected on a flat, 2D screen, the hallway must be animated to adjust precisely based on the location of riders. That’s exactly what needed to be developed for the landmark Spider-Man ride at Universal Orlando. If viewed from a single spot, the ride’s virtual sets would appear to lengthen and recede, squash and stretch. But when precisely calibrated to a moving vehicle and its riders points-of-view, the scenes truly feel like “extensions” of the ride’s physical sets.

Obviously since (and largely because of) 1999’s Spider-Man ride, The Age of the Simulator has lead to screens become the primary way of placing guests into stories. As a result, “squinching” can be seen in virtually all rides that have moving guests pass by stationary screens.

Even outside of Disney and Universal Parks, “squinching” adds depth and realism to all kinds of dark rides. For example, the Lost Legend: Curse of DarKastle masterfully used the technique as guests entered, moved through, and exited each scene (see here). A variation of the concept is what continuously alters the perspective on Guardians of the Galaxy – Mission: BREAKOUT! as guests bob up and down, and even overexaggerates the launch on Harry Potter and the Escape from Gringotts.

When squinching is done right, you’re unlikely to even notice it. The more precisely animators capture the “real” perspective guests would see in a “real” space, the less your brain even registers the motion of the animation. When it’s absent (or done wrong), it’s jarring and immediately reveals that the scene is a screen with no true depth.

In 1999, Disney engineers, executives, and thinkers had a wild idea: what if they could finally solve the number one issue raised by Disney World guests…? Naturally, surveys indicated that guests hated waiting in line, and since Disney Parks’ attendance was growing faster than the parks’ capacity, it was beginning to seem that Disney World was more “waiting” than “doing.” Their idea was revolutionary.

Don’t misunderstand; we (and many others who study the industry) valiantly argue that Disney should get rid of FastPass altogether. But at least in the Blue Sky dreams of industrial-organizational psychologists, FastPass was going to make it so that guests would spend very little time waiting, and more time in shops and restaurants. Ideally, use of the system would be so proficient and so natural, FastPass would be the line for the ride, with a paltry queue of guests who preferred to wait “stand-by” – literally, a secondary option for guests who didn’t mind waiting for an opening, somewhat like a Single Rider line.

Of course, FastPass has gone through many iterations and has never reached that peak, 100%, utopian utilization early designers seem to have hoped for… Part of factoring FastPass+ selections into pre-visit planning (alongside ADRs, hotels, and transportation) was supposed to be to “socialize” FastPass, ensuring absolutely equal access. Now, guests are “guarunteed” at least 3 low-wait attractions, but (as we argue in a Special Feature editorial) FastPass means every other wait will be much, much longer. The end result? The “Stand-by” line isn’t really “stand-by.” It’s the regular ole’ queue line that you’ll be in for many attractions.

Fans of Disney and Universal Parks spend an awful lot of time talking about “theme,” but they don’t always mean the same thing. Sometimes, “theming” is used to mean “decoration,” like a queue that’s “themed” as an ancient temple. Sometimes “theme” is used to mean intellectual property (see, IP), as in “a ride themed to The Little Mermaid.

But Imagineers look at “theme” in a much bigger context. The “Imagineering in a Box” course defines theme as a unifying idea; the deeper meaning; the thing that a story is about. In that framing, the “theme” of Animal Kingdom (as often and popularly shared by creative lead and former Imagineer Joe Rohde) is the supreme and intrinsic value of nature. Nested within it, for example, Pandora’s theme is the power of conservation; Asia’s is the devastation of habitat loss; Africa’s is the balance between economy and ecology and the untradeable value of the latter.

The “theme” is, in effect, a north star. Design elements and IPs should support it, but are not “themes” themselves… at least, not in Imagineering lingo.

WDI – Walt Disney Imagineering – is the research and development arm of Walt Disney Parks, Experiences, and Consumer Products. Originally founded in 1952 as Walt Disney, Inc., this new engineering company was tasked with creating initial designs for Disneyland. When Walt’s brother Roy objected to the name (which tied the Walt Disney Studios brand to this experimental, “doomed” park), it was renamed WED Enterprises (for Walter Elias Disney), which remained the name throughout all of Walt’s life. Obviously, the engineering group and its Disneyland became so integral to the brand, it was purchased and absorbed by Disney in 1965, and renamed Walt Disney Imagineering two decades later, in 1986.

Imagineers – a portmanteau of imagination and engineer – are the Cast Members who create, design, and construct Disney Parks and attractions. Make no mistake: Imagineers come from varied backgrounds and represent the fields of illustration, architecture, engineering, lighting design, show writing, graphic design, and many more fields.

Follow one. If you step into Frontierland, Big Thunder pulls you further; in Rockettower Plaza of Tomorrowland, you’ll be attracted toward Space Mountain.

Try it yourself! Any time you come to a crossroads in a Disney Park, stop and look around you. More than likely, you’ll see obvious, attractive “weenies” in each potential direction. And like showbuildings, the hub-and-spokes layout, and so many other elements “invented” for Disneyland, “weenies” have been extrapolated beyond Disney Parks, with the concept (and the term) used in urban planning, museums, science centers, and more.