UNDER REFURBISHMENT! You know I love to keep things fresh around here, and as a result, this feature is currently under construction! As I finish up edits over the next few days, you may encounter outdated information, repeated or disjointed sections, or “past perspectives” that refer to current events in the future tense. If you don’t mind sifting through some rough edges, I think you’ll still enjoy it… and check back soon for a fully refurbished story!

Horizons 1 is now departing. Our final destination today: the twenty-first century.

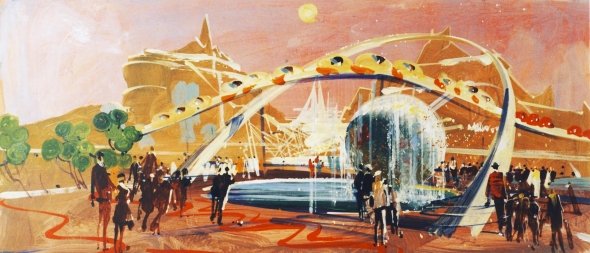

For Walt Disney Imagineering, it was a destination a long time coming: the future. Since the cast of designers who would create Disney’s theme parks was formed in 1952, great effort has been spent imagining (and then re-imagining) what tomorrow could bring… And more often than not, Imagineering’s visions of tomorrow have been surprisingly prescient!

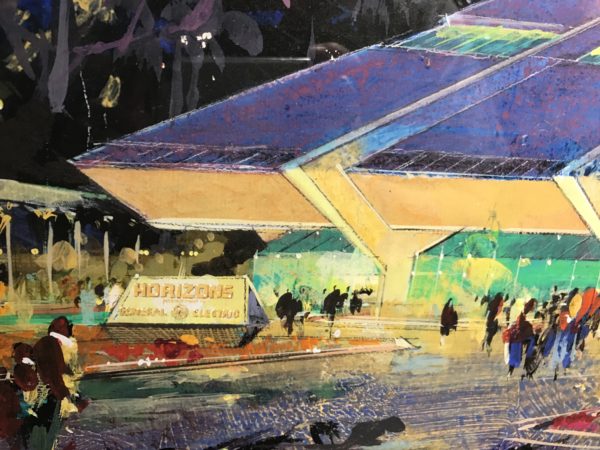

But all glimpses into the future conjured by Disney’s designers paled in comparison to the ride that – for many fans of classic Imagineering – reset the standard and the timeline. For fans of the original EPCOT Center and the heady, intellectual, reflective, and progressive values it stood for, time is measured before and after HORIZONS.

Today, we’ll glimpse the future as envisioned by EPCOT Center on a round-trip, time-traveling journey that starts in the past. Even today – long gone from park maps – it ranks among the pantheon of Disney Parks’ most ambitious, elaborate, and massively-scaled E-Tickets ever created.

But even more, Horizons was a grand, ambitious landmark of what EPCOT could be and what Imagineering could do; a project reflecting the greatest intuitions and impressions of a graduating class of designers passing their skills on to the 21st century. And in the minds of many thematic design aficionados, it was as close to a masterpiece as Disney’s ever been, standing alongside Pirates of the Caribbean, Haunted Mansion, Indiana Jones Adventure, and Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance.

What made Horizons a ride that’s transcended into the upper echelons of Imagineering’s most beloved projects? To glimpse the future as envisioned by EPCOT Center on a round-trip, time-traveling journey, we’ve got to start in the past…

And before we head off, remember that you can unlock rare concept art and audio streams in this story, access over 100 Extra Features, and recieve an annual Membership card and postcard art set in the mail by supporting this clickbait-free, in-depth, ad-free theme park storytelling site for as little as $2 / month! Become a Park Lore Member to join the story! Until then, let’s start at the beginning…

Futurology

“What will tomorrow bring?” It’s a question that’s practically engrained in the genetic code of humanity. Since at least the writings of Chinese historian Sima Qian two thousand years ago, humans have sought out grand patterns in mankind’s machinations and used them to wonder aloud what might lie just over the horizon.

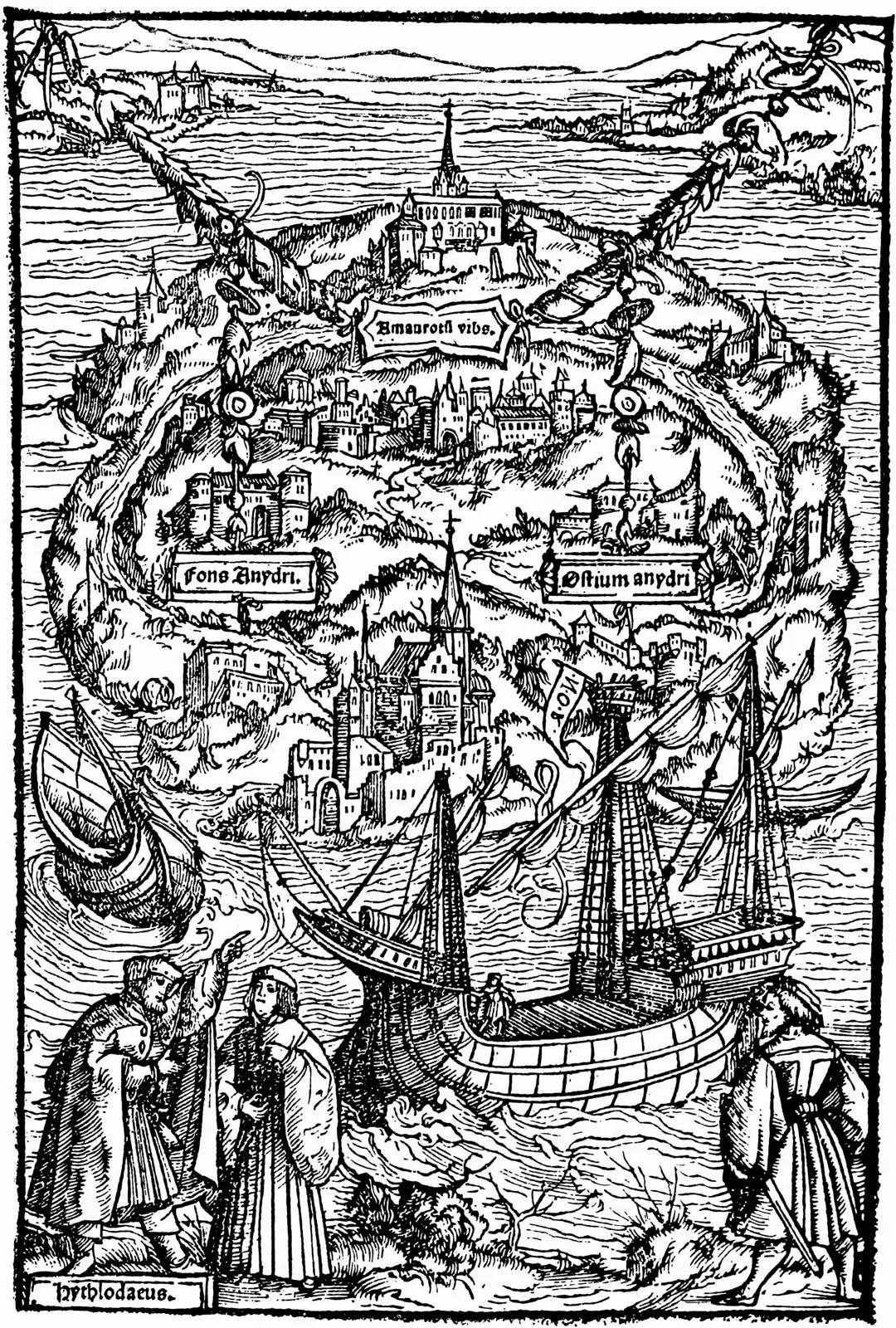

By the sixteenth century, the Western world had Sir Thomas More’s Utopia – a glimpse into a fictional, future-set society of public goods, universal healthcare, and religious tolerance. A century later, advances in math introduced calculations of statistics and probabilities, which would power the formulas needed to determine the future values of assets – an essential ingredient of the Industrial Revolution to come.

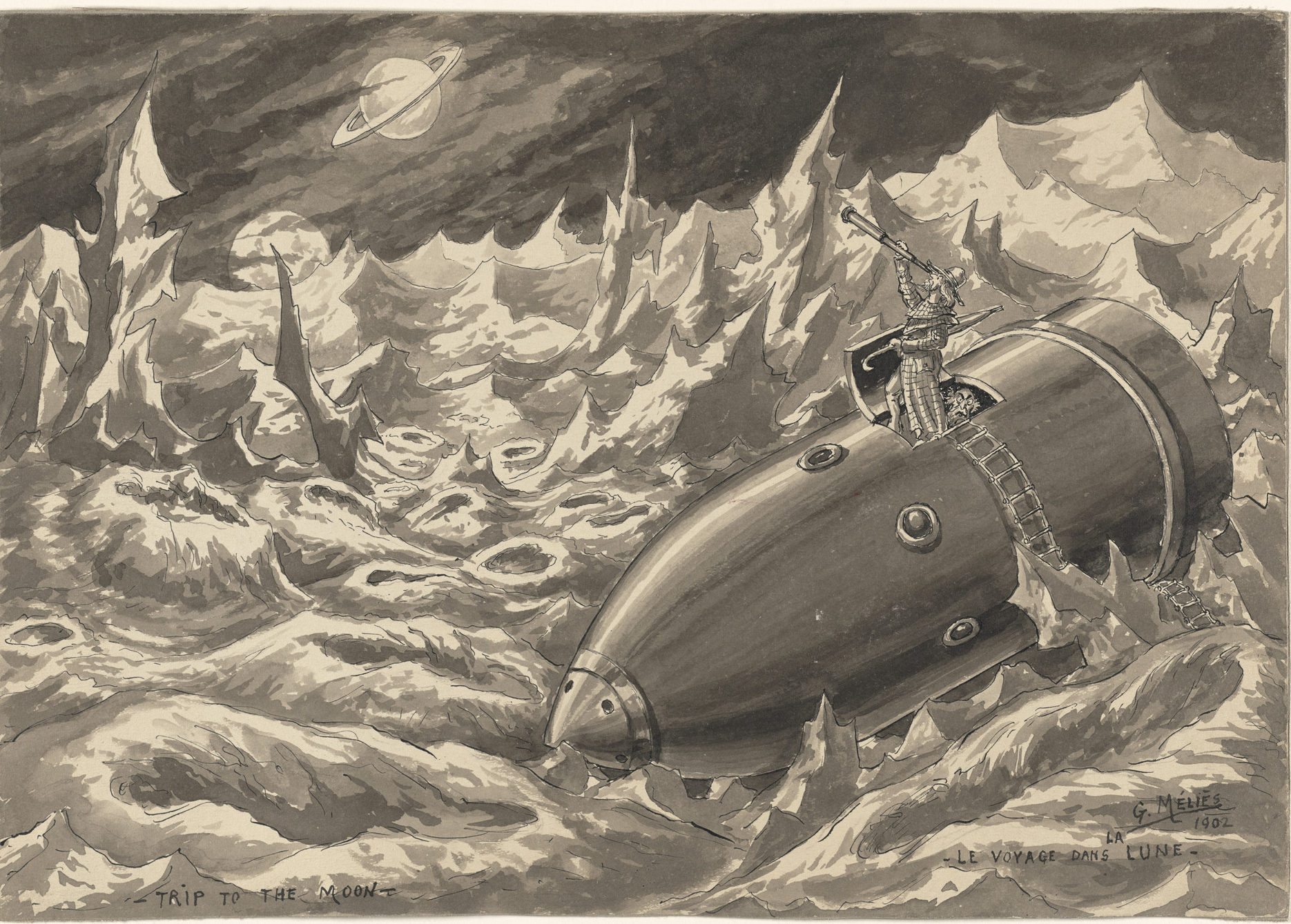

With the turn of the 20th century looming – and humanity’s command of electricity and internal combustion engine hot on its tail – “futurology” got a jump start. Prolific writers like H. G. Wells and Jules Verne ushered in the genre of “science-fiction” – grand, adventurous stories set in worlds to come, predicting technological and social progress all ostensibly rooted in sound scientific principle.

Before long, tales of the “possible impossible” leapt from the page to the screen. From early, nascent “moving pictures” (like Georges Méliès’ fabled 1902 adaptation of a Verne novel in A Trip to the Moon) to the era of sci-fi “B-movies” in the ’50s, the public literally saw the future sprawl before them: time machines, visitors from other worlds, unthinkable inventions, and the dawn of the Space Age…

The ingredients had coalesced, and humanity spent the earlier half of the 1900s in the dreamy grip of tomorrow. Aluminum houses. Microwave ovens. The promises of plastics, asbestos, and lead. Rockets and submarines. The all-consuming power of the atom. Mass transit. Chemical discovery. “World Peace.” Anything seemed possible. Even if it didn’t look quite the way philosophers, artists, and historians had imagined, the future had arrived.

So it’s no surprise that when Disneyland – a perfect encapsulation of mid-century Americana – opened in 1955, one of its opening day lands promised to lift the curtain of time,. Tomorrowland promised “a vista into a world of wondrous ideas, signifying Man’s achievements… A step into the future, with predictions of constructed things to come. Tomorrow offers new frontiers in science, adventure and ideals. The Atomic Age, the challenge of Outer Space and the hope for a peaceful, unified world.”

But for Walt Disney and his team of “Imagineers,” the threshold between today and tomorrow wouldn’t be crossed in Disneyland at all. Instead, the blueprints for the future would be drafted in a perfectly appropriate laboratory…

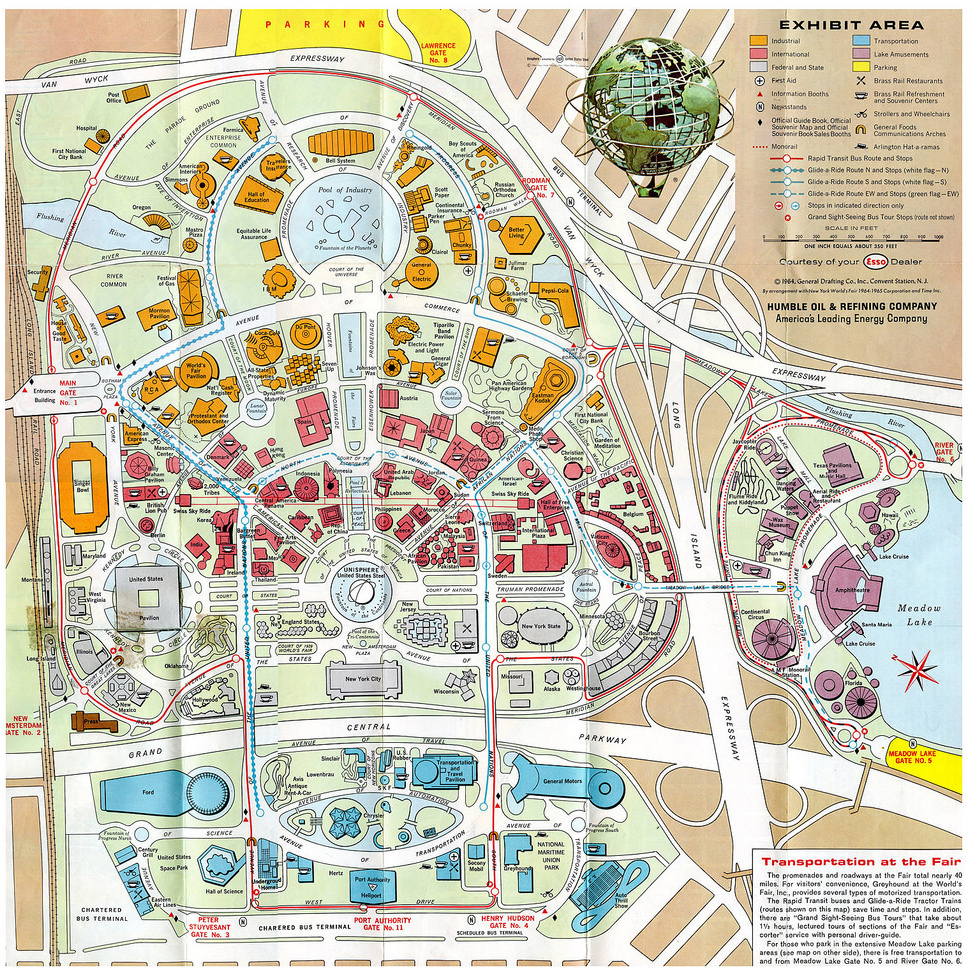

It’s worth segueing from the dawn of Horizons for just a moment to remember that Disney’s next great leap into the future was far from Imagineering’s warehouses in Glendale, California. At least for a time in the early 1960s, it was Queens, New York where the future unfolded. That was thanks to the 1964 – 65 New York World’s Fair – a momentous international exposition perfectly positioned at the pinnacle of mid-century America.

In that way, the World’s Fair was a win-win; companies were delighted to pay Disney to design, fabricate, and install attractions that could leverage Disney’s name and attractions as showrooms and ambassadors to global audiences, while WED could work with “company money,” spending big to pioneer cutting-edge ride systems, show technologies, and new products at the Fair. In the story of Imagineering, the World’s Fair served as a pivot point after which Disney found itself armed with new high-capacity ride systems, humanoid Audio-Animatronics, and – important for us today – the very concept of corporate-backed pavilions providing glimpses into the past, present, and future…

EPCOT – a vista of wondrous ideas

At the close of the World’s Fair, WED Enterprises found itself on a new trajectory. Projects that had been variously stalled by or made possible by the Fair were back on, ushering in an era remembered as a classic height of Imagineering: “it’s a small world”; Walt’s New Tomorrowland with its PeopleMover, Carousel of Progress, and Adventure Thru Inner Space; New Orleans Square, Pirates of the Caribbean, and eventually, the Haunted Mansion…

Grand as the breakthroughs and innovations of the World’s Fair might’ve been for WED, by all accounts, they paled in comparison to what Walt himself was dreaming up next. When it’s all said and done, Walt’s closest friends often say that above all else, Walt was an optimist. And though the “World on the Move” he helped shape for Disneyland’s New Tomorrowland was a soaring example of his optimism in action, it was merely a taste of what E.P.C.O.T. would entail…

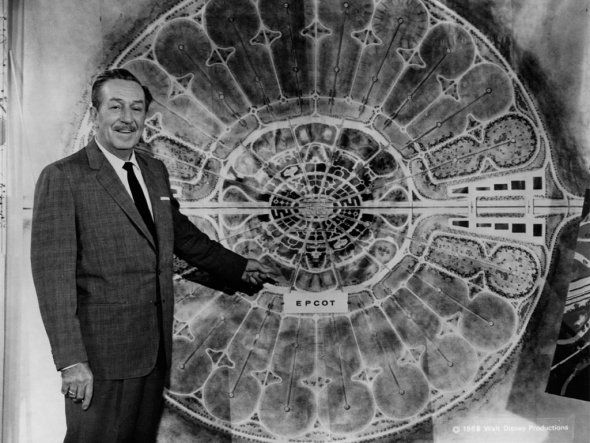

Walt’s “Florida Project” was where he envisioned applying all that Disneyland had merely tested. The Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow he planned to build would be a living city, master-planned for efficiency and convenience.

From its central hub of stores, restaurants, and hotels, the city’s Peoplemovers would be propelled outward like arteries, carrying residents to suburban cul-de-sacs where homes would be subject to continuous updates by American corporations. EPCOT would be an ever-evolving showcase meant to be a living blueprint for all modern cities to come after.

“EPCOT will take its cue from the new ideas and new technologies that are now emerging from the creative centers of American industry. It will be a community of tomorrow that will never be completed, but will always be introducing, and testing, and demonstrating new materials and new systems. And EPCOT will always be a showcase to the world of the ingenuity and imagination of American free enterprise.“

Friends say that, as Walt was lying in his hospital bed, dying of lung cancer, he would look up at the tiles on the ceiling, using them as a grid to explain the layout of the city he saw in his head. Of course, once Walt passed away in December 1966, those left behind at Walt Disney Productions knew better than to press forward with such an ambitious, impossible task without Walt at the helm. Instead, the new “Walt Disney World” that opened in 1971 would become a recreation resort anchored not by a city, but by Magic Kingdom.

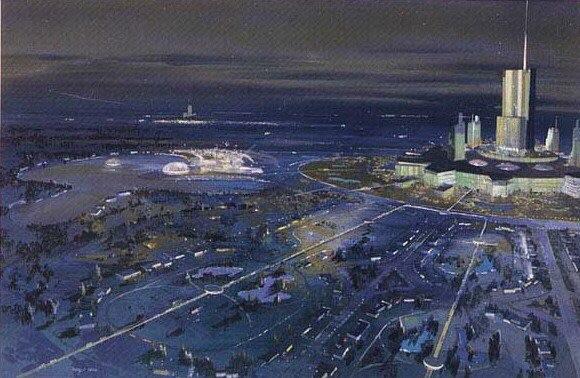

By the mid-1970s, though, Walt Disney World was ready for growth in the form of an unprecedented second theme park on the property. At that time, then-CEO Card Walker began to toy with the idea of incorporating the essential ideals and core values of Walt’s EPCOT – industry, optimism, and futurism – with the tried-and-true concept of a permanent World’s Fair in Orlando. Built on the principles of tomorrow but rooted in the models of the past, it would be Disney’s most fascinating experiment ever. Read on…