Sponsoring the Future

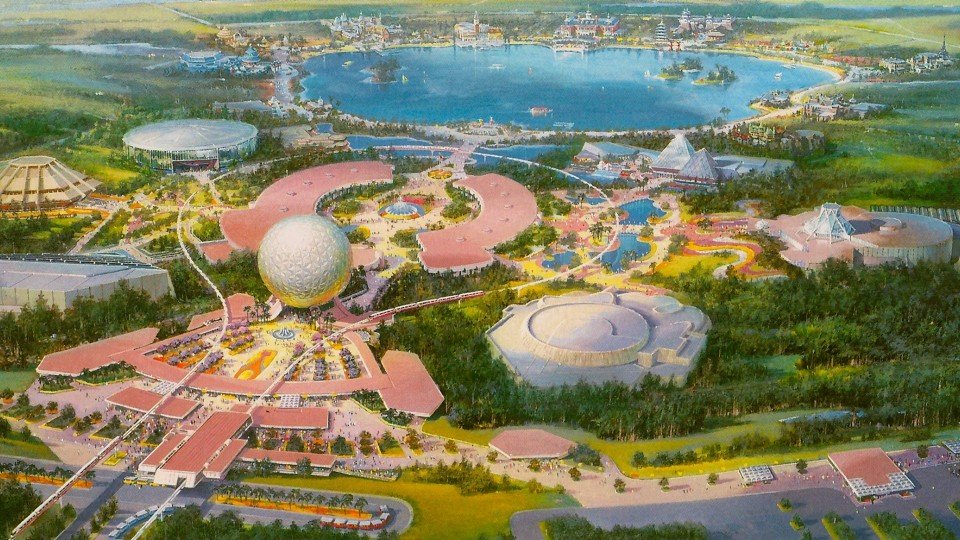

Publications suggest that plans for an international “World Showcase” and a “permanent World’s Fair” (originally envisioned for the Bay Lake area) existed nearly as far back at Magic Kingdom’s opening – 1972. It wasn’t until 1976 that models of EPCOT Center (above) began to resemble the park we know today – of “World Showcase” and “Future World” serving as symmetrical counterparts and complements.

It was a major shift in planning in 1977 that saw the two realms “flip” (positioning Future World as the park’s entrance). This new and nearly-final form also began to cement a now-essential piece of the EPCOT Center we know: topic-focused pavilions.

Even the earliest of the late-’70s models and illustrations of the park show Spaceship Earth in its final place; the symmetrical wings of Communicore beyond; the energy pavilion (the only pavilion whose placement never moved due to its solar panel roof); and early designs for the pavilions that would eventually celebrate the seas, land, and transportation.

What these pavilions still lacked, of course, was a firm idea of what exactly would go inside of them. By 1978, Disney had already made its first sale when General Motors agreed to support the transportation pavilion, signing on to underwrite the development of what would become the Lost Legend: World of Motion… and in exchange, to use Disney Imagineering’s skills (and the good will of having their brand associated with Disney at all) to integrate General Motors’ branding and messaging into a ride focused on their field.

Likewise, General Electric made for an obvious companion to EPCOT Center. Disney and General Electric had been flirting with partnership since the ’50s when Walt had drawn them in on plans for an entire land at Disneyland dedicated to the company’s founder – Thomas Edison – and an attraction focused on the wonders of electricity and modernization.

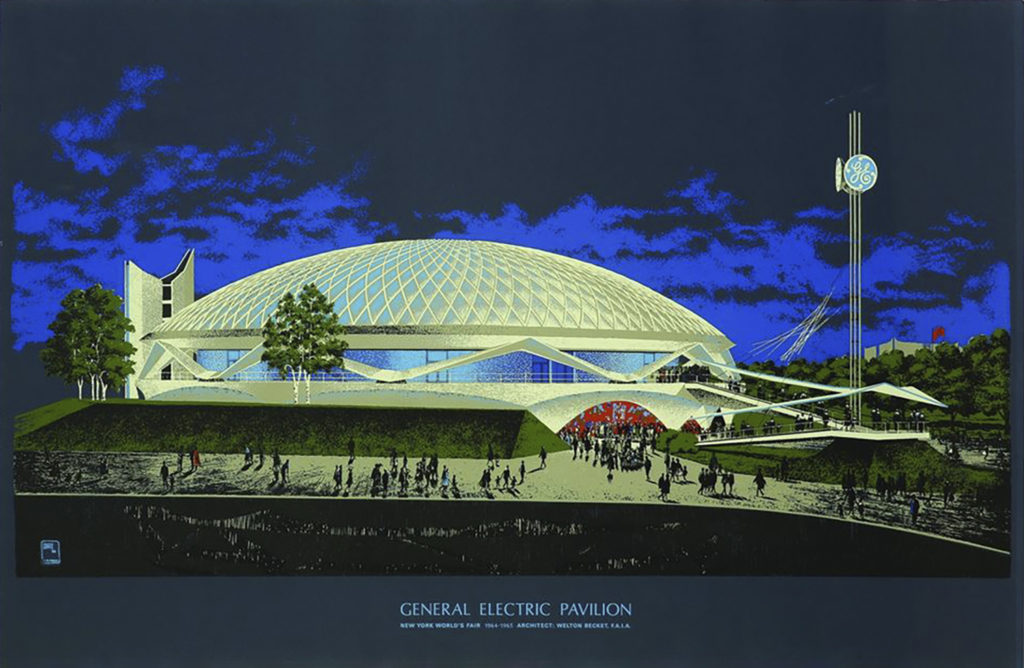

Though Edison Square hadn’t come to pass, General Electric had circled back on the concept with Disney for the 1964 World’s Fair, creating the Modern Marvel: Carousel of Progress. (They continued to sponsor the attraction when it was relocated to Disneyland at the Fair’s end, and again when it traveled to Central Florida in 1975.)

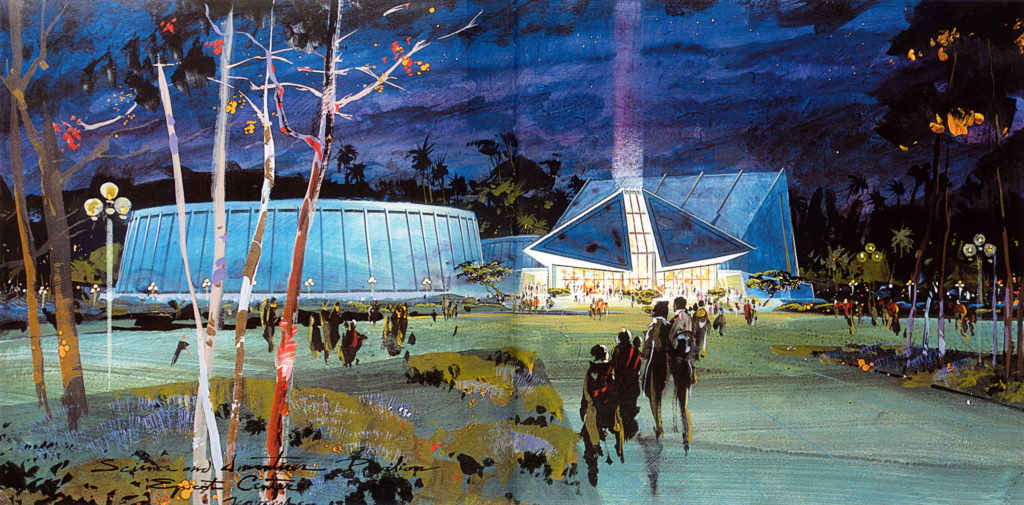

In 1979, Disney Legend Herb Ryman crafted the concept art above, of a so-called “Science & Invention” pavilion, custom-made to be sponsored by General Electric. Very little is known about what the Science & Invention Pavilion might’ve contained… maybe even by those who worked on the project. It’s likely that this concept largely developed as a way to sell the concept to General Electric, promising that their up-and-coming appliances would populate a show floor as “science and invention” incarnate.

However, a leadership change at GE moved legendary businessman Jack Welch into the company’s Vice Chairman role. (He would ascend to Chairman and CEO soon after, in 1981.) Some sources insist that it was Welch who expressed to Disney that he didn’t believe that the Science & Invention pavilion was forward looking enough to meet GE’s needs.

Others say it was Disney who contested that a pavilion focused solely on electricity simply wasn’t thinking big enough, and that GE needed to free their pavilion from Edison entirely to tackle the topic of progress more globally. In either case, Science & Invention fell off the topic as quickly as it had been drafted.

FutureProbe

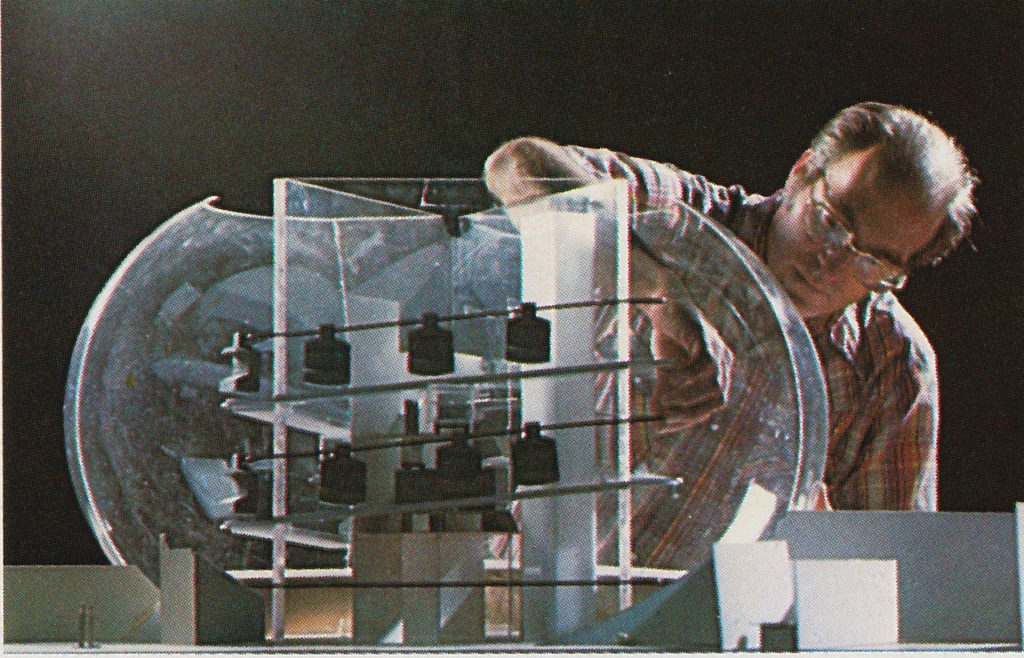

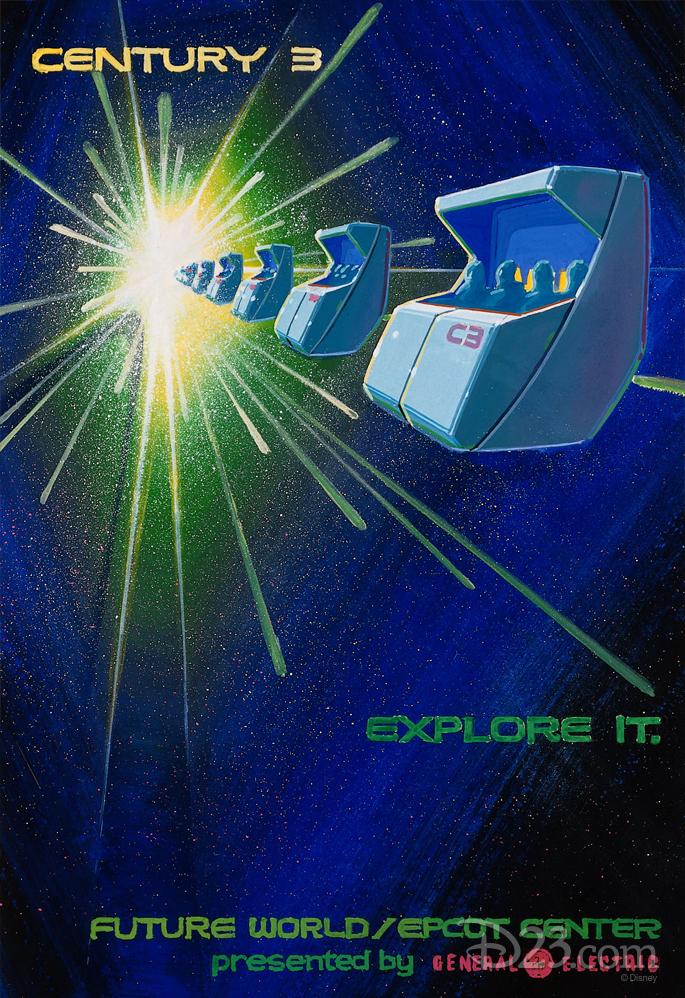

An early 1979 model (above) reveals Disney’s solution: a pavilion codenamed “Century III” (in the 4:30 position occupied today by the Seas), anchored by a ride through life in the third century of America (1976 – 2076). The concept must’ve resonated, because in October 1980, GE signed on the dotted line, committing a reported $50 million for the design and development of an EPCOT attraction that would explore life in the future.

What did not stick was the name. GE allegedly worried that expecting “Century III” would make intuitive sense to Americans was a stretch, much less that it communicated what was inside to international visitors. Instead, with GE signed on, the ride moved into development as “Futureprobe.”

Thankfully, there’s much to learn from General Electric’s Research and Development lead Ned Landon in a multi-part interview archived on Progress City, U.S.A. Landon said of the ride’s development, “We had ample opportunity to ask questions, to suggest changes, to add our own ideas. Some of our people who had worked closely with the Disney organization since the planning for the GE Carousel of Progress at the 1964 New York World’s Fair were instrumental in getting GE’s EPCOT Center project off and running.”

Even as “Futureprobe,” the concept – developed by project lead George McGinnis – was in place: from a FuturePort queue resembling a transit station of tomorrow, guests would board a chain of continuously-moving vehicles resembling Disney’s fabled Omnimovers, but suspended from an overhead track. The vehicles would whisk guests through physical sets showcasing life in the 21st century in three environments: the desert, the deep ocean, and outer space.

Its grand finale, though, would introduce an incredible, cutting-edge element. In the building’s core, Imagineers planned to install three domed Omnimax screens on their sides, arranged in a triangle. That way, having ascended through the building’s scenes, the suspended Omnimovers could return to the unload level along a clever spiral descent, always facing outward and transitioning seamlessly from one dome to the next.

Certainly, Futureprobe stood out among the wonders of EPCOT Center’s conceptual Future World. Here was an attraction dedicated not to a particular area of science, technology, or industry, but to ideas much bigger: Possibility. Optimism. Hope. And via GE and project lead George McGinnis, the role of this unusual pavilion would only grow…

New Horizons

Ultimately, one last major reorganization of EPCOT Center’s Future World would see the GE pavilion leap from the 4:30 spot to its final, 9 o’clock position in the park’s lineup. There, it would gain a new facade, too – a golden showbuilding that at once echoed an ancient, pyramidal structure of the past while also resembling a landed saucer from the future. Its elaborate and dramatic angles also served to emphasize its three-dimensionality (compared to many other Epcot pavilions, designed with a more “flat,” silhouette-focused perspective). The building’s roof even created its own distant horizon line.

Speaking of which, the GE pavilion also gained a new name. Said Landon:

“[Futureprobe was] not bad. But we always thought it had a rather uncomfortable medical connotation. We thought Horizons was just right. There always is a horizon out there. If you try hard enough, you can get to where it is – and when you do, you find there’s still another horizon to challenge you, and another beyond that…

If Horizons had a subtitle, I’d vote for ‘An Achievable Future.’ To me, that phrase means a lot about what we’re trying to do and say. We’re not predicting a better world based on wild guesswork or imaginary science fiction. Instead we’re saying that today’s technology – scientific understanding – is so advanced that it gives the human race magnificent options to shape a better tomorrow. To achieve a future with greater promise for everybody.

Without a doubt, Horizons would be one of the most elaborate and expensive attractions ever undertaken by WED Enterprises. As gargantuan in scale as it was in spirit, the ride would rival Pirates, Haunted Mansion, and any of its own EPCOT Center sisters. Site preparation for Horizons began on August 5, 1981 with construction beginning January 1982 – far too late to open with EPCOT Center that October, but well-positioned as a “Phase II” expansion of the park.

Behind the scenes, we know that a $10 million reduction in scope meant that the Horizons that arose between the transportation and energy pavilions looked slightly different that what McGinnis and his team at Imagineering had initially planned.

Reportedly, about 600 feet of length was cut from the ride track – most of it in the ride’s opening ascent and its subsequent trip down past the Omnimax screens. (The triple-domed, double-pass spiral descent was reduced to a single pass by two domes, both inhabiting the widest and highest part of the showbuilding, 78 feet tall.)

Since the Omnimax domes had been recast as an opening piece of the ride, a new finale was needed. Impossibly ambitious for the era (and five years before STAR TOURS), McGinnis envisioned the ride ending with each vehicle participating in its own, personal-sized simulator… a 31-second video that would be projected only to your vehicle, sweeping and soaring through a futuristic landscape.

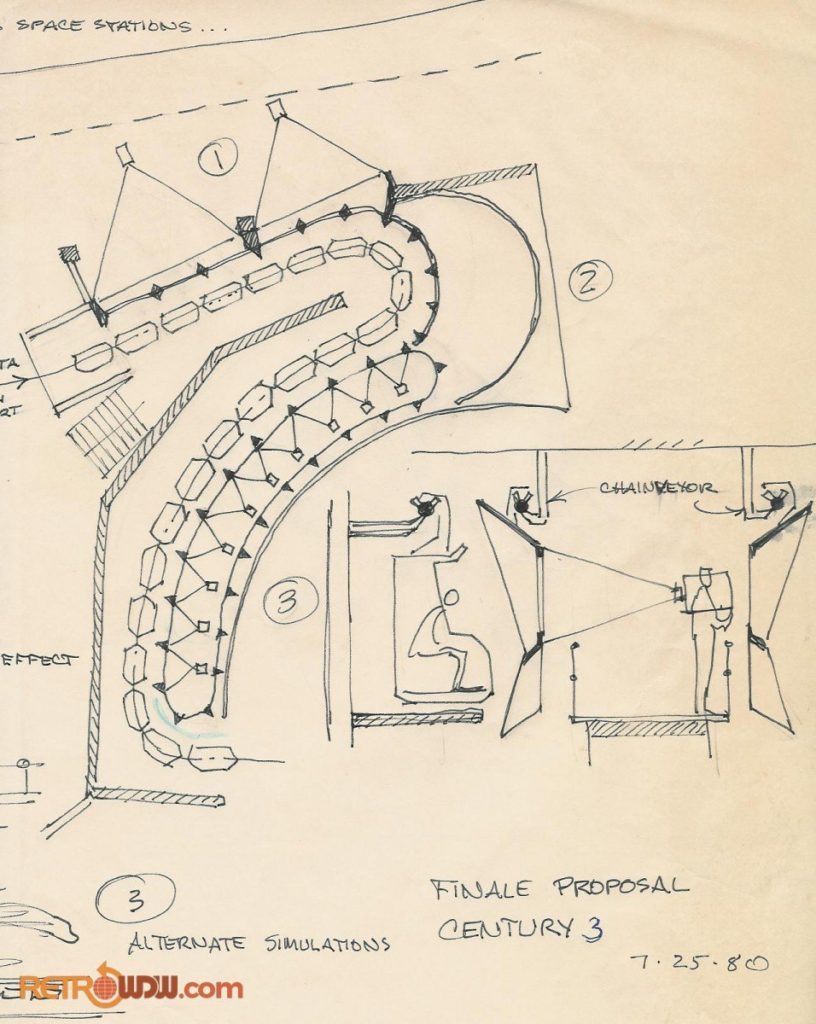

McGinnis’s hand-drawn concept (above) was ingenious. In a sort of evolution of the Haunted Mansion’s Hitchhiking Ghost effect, the chain of Horizons’ Omnimovers would glide past a continuous wall of rear-projection screens, where seven GE projectors would work in perfect unison to send a projected “simulator” video down the line, moving precisely from projector-to-projector to stay aligned with a single one of the ride’s 174 suspended vehicles.

And if that weren’t novel enough, this “simulator” finale would also be a “Choose Your Tomorrow,” with guests literally voting via in-cab buttons on which future glimpsed as physical sets in the ride they wanted to see play-out for themselves: life in the desert, deep sea, or outer space.

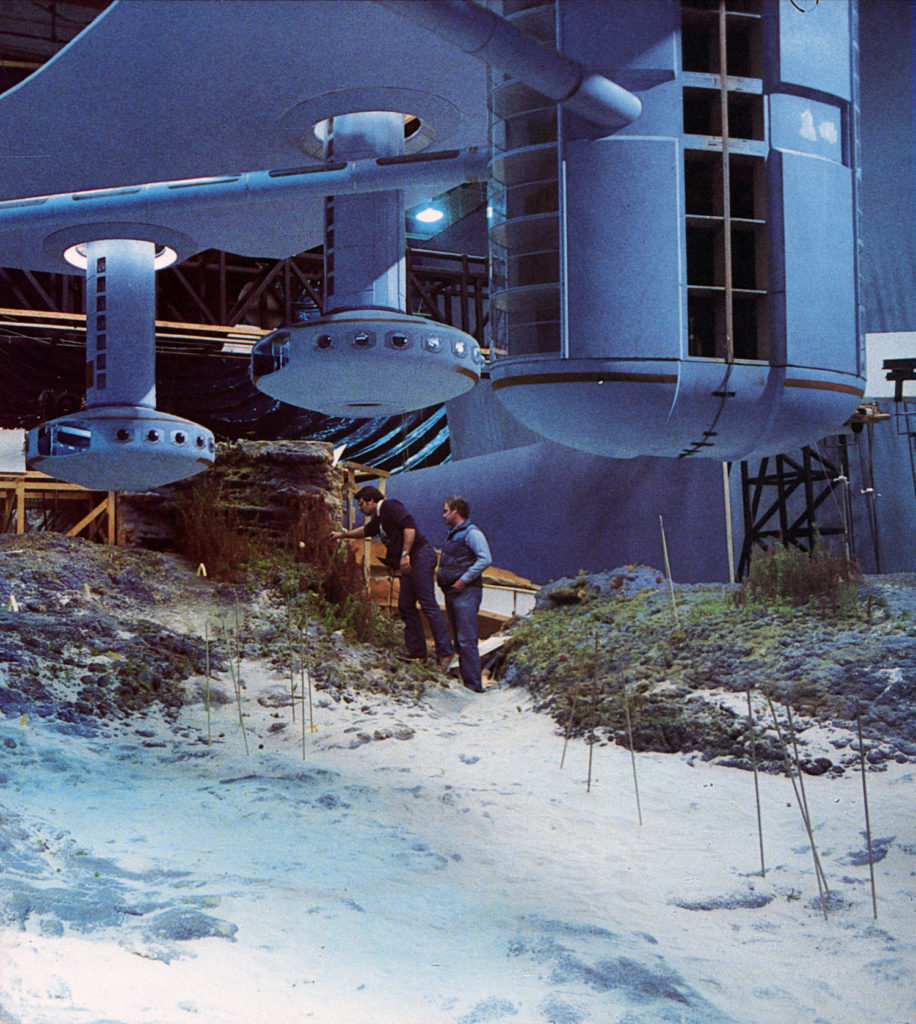

The three 31-second clips were filmed on massive scale models (erected in a hangar in the Burbank Airport in Los Angeles) that took over 30 model-makers a full year to create. The “dessert” model, for example, was 32 feet wide and 75 feet long.

Altogether, Horizons offered an incredible 137,00 square feet of space between two stories, with its suspended Omnimovers traversing 1,346 feet of track – an absolutely epic, EPCOT-sized, 15 minute dark ride experience.

Cleverly, Imagineers wanted the attraction and its celebrational look at the world ahead to feature some familiar faces. The attraction would be the “spiritual sequel” to the Carousel of Progress itself. After all, Carousel of Progress traced how innovation improved the lives of John, Sarah, and their children through the 20th century. Now, this epic new attraction would continue their story, following the same family through the 21st century, to see how life changed at the crossroads of Future World’s topics.

Horizons opened on October 1, 1983 (the park’s first birthday). The Omnimover ride through the future was immediately a fan favorite and inspired a new generation. Horizons established a very clear vision of what the future as seen from 1983 might look like, and it’s a vision that’s been carried on by those who saw the ride back then.

So what awaited inside the stunning golden pavilion that brought all of EPCOT’s themes together? Read on, as we step on board and explore the horizons of civilization….