Circling back

Where were we? Disneyland’s Circarama theater had opened in Tomorrowland in 1955 with “A TOUR OF THE WEST” – a travelogue through Californian desert landscapes presented in a groundbreaking, 11-screen format that surrounded guests in a full wraparound picture.

In 1960, the new Circarama film Walt had developed for the 1958 World’s Fair in Belgium was brought home. Well, its third home, in its third country. “AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL” opened at Disneyland in 1960.

It played until the arrival of the Lost Legend: The Peoplemover and Walt’s New Tomorrowland in 1967, when the 360-degree theater was expanded to take over the entirety of the land’s north showbuilding. A newly filmed presentation (also titled “AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL”) debuted alongside the new land – the third surround-screen production in the building, but the first presented in a newly-refined nine-screen format called Circle-Vision 360° .

Of course, Disney’s use of Circle-Vision technology was just getting started.

Just a few years later, Magic Kingdom opened at the brand-new Walt Disney World in Florida, with its own nine-screen Circle-Vision 360°, showing “America the Beautiful” just like its Californian sister. Like at Disneyland, Magic Kingdom’s installation was given a prominent position in one of the mirrored showbuildings along the land’s main entry (albeit, in the south building rather than Disneyland’s north… see the screen protruding in the lower right, above?)

Over the next two decades, Magic Kingdom’s Circle-Vision theater would play “MAGIC CARPET AROUND THE ROUND” (1974 – 1975), an encore of “America the Beautiful” (1975 – 1979), “Magic Carpet” once more (1979 – 1984), and the new “AMERICAN JOURNEYS” for the next decade.

Unsurprisingly, the inspiring film format – perfect for a travelogue – became the de facto attraction in EPCOT Center’s World Showcase upon its 1982 opening. Both the China pavilion and the Canada pavilion offered Circle-Vision films as cultural ambassadors, capturing the “Wonders of China” and celebrating “O Canada!,” respectively. Impressions de France in the France pavilion likewise resembles the technology, but with only five screens in a 200° wrap-around configuration.

The year after EPCOT Center opened, Tokyo Disneyland debuted with a Tomorrowland closely modeled off of Florida’s, including a Circle-Vision theater in the “south” showbuilding along the land’s entry corridor, even playing “American Journeys.” But upon its 1983 opening, a glaring problem was growing…

Yesterdayland

When first pioneered by Walt and Iwerks in 1955, the idea of a 360° theater was sincerely a cutting-edge display of the filmmaking of the future – a glimpse into what the next leap forward in movies might be.

By its Japanese debut in 1983, Circle-Vision was approaching its 20-year anniversary, and it had to have been clear that the technology wasn’t really going to take off in an applicable way outside of Disney Parks. It’s really not so different from the Monorail or the Peoplemover, which Walt had intended as mere prototypes of actual, utilitarian technologies of tomorrow, but had become so closely associated with theme parks as to negate their public use.

Meanwhile, the new Lost Legend: Captain EO parked directly across from Tokyo’s Circle-Vision theater offered a much more current idea of cinema’s next steps: starring a true global celebrity and crafted by the filmmakers behind Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and The Godfather, Captain EO was a pop culture phenomenon. It was also the debut of the “4-D” film, mixing in-theater special effects like fog, lasers, and starfields. Now this was the future of film, leaving Circle-Vision and its “American Journeys” travelogue in the dust.

But Circle-Vision wasn’t the only problem. At the three Tomorrowlands across the globe, Imagineers began to face the dreaded “Tomorrowland Problem.” We’ve discussed this recurring roadblock in a number of Lost Legends features, but it amounts to a simple concept: tomorrow always becomes today. And if you wait long enough, it’ll become yesterday, too.

Put another way, if Tomorrowland were to be dedicated to actual displays of potential futures, emerging technologies, and sincere innovation, each Tomorrowland across the globe would need constant, continuous, and costly upgrades, forever. To keep up with pop culture, the very fabric of Tomorrowland would need to change… and keep changing.

And plunged into the dark, dismal, gritty vision of the future that had invaded pop culture during the 1980s (thanks to Alien, Blade Runner, Star Wars, and even TRON), the hippy-dippy, sleek, concrete, Space Age-influenced Tomorrowlands in California, Florida, and Tokyo were looking like yesterday’s news. An optimistic world of swirling white and red rockets, pastel Peoplemovers, and gentle, geometric architecture looked naïve and outdated.

Change was needed. And change was coming.

Timeless tomorrow

Luckily, Disney had just the test bed for changing up the concept of Tomorrowland: EuroDisneyland. In fact, in a 1989 annual report acquired, scanned, and posted by our friends at CafeFantasia for Medium, the earliest reports of a new strategy began to emerge.

The report – less than three years out from the French park’s 1992 opening – included a land-by-land breakdown of Fantasyland, Frontierland, Adventureland, and… something new…

Inspired by Jules Verne, Leonardo da Vinci, H.G. Wells and other visionaries, Discoveryland will acknowledge man’s achievements and contemplate possibilities for the future.

A-ha! While both Disneyland and Magic Kingdom still clung to the outdated styles of the ’70s, Discoveryland would solve the “Tomorrowland Problem” by intentionally looking to the past. Rather than trying to actually predict what architecture, science, and industries of the future may be like, Discoveryland would be rooted in the literary, adventurous, and unreal futures envisioned by European writers and thinkers of the 19th century (and earlier).

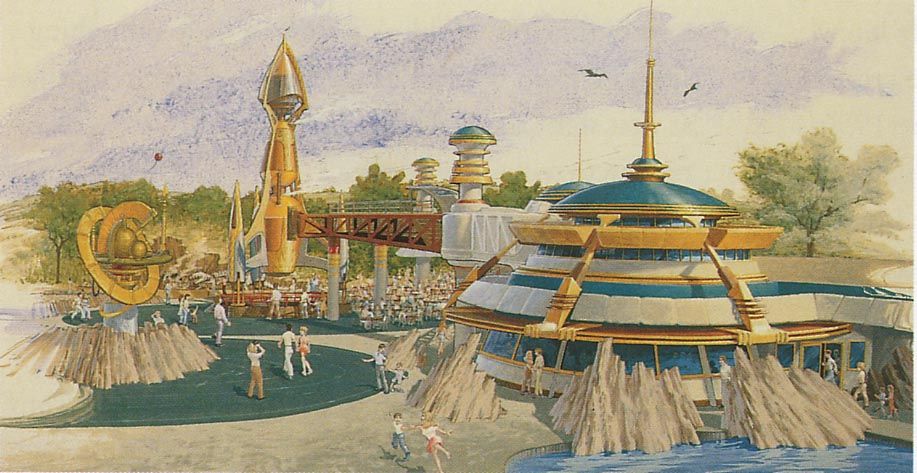

In fact, it would be a glittering, golden world inherently different from the sterile, white Space Age tomorrows in the United States; filled with bubbling lagoons, lush hillsides, volcanic rocks, oxidized copper, zephyrs, hot air balloons, and submarines. Its attractions would include a walkthrough the Nautilus from Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, a golden, grounded Orbitron of swirling rockets modeled after a Da Vincian planetary model, and what was expected to be the land’s uniquely-European anchor…

Again from the ’89 Annual Report:

Other attractions will include a 3-D film and a 360-degree Circle-Vision film based on the theme “France, Europe and the Future”.

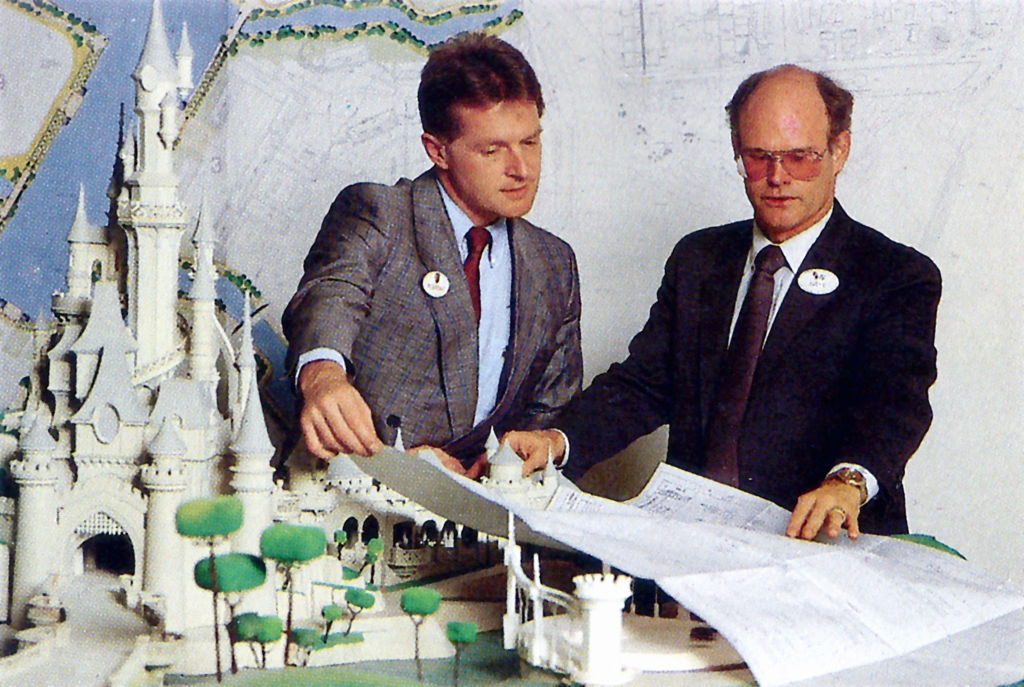

In fact, Disney Imagineers would construct for Discoveryland one of the most elaborately stylized Circle-Vision 360 theaters yet as evidenced in the Passholder-exclusive model, above. Now, here’s where things get interesting.

Yes, Disney’s 11-screen “Circarama” had been around since 1955, with its 9-screen “Circle-Vision” successor taking over in 1967. Yes, we just got done suggesting that the technology was no longer an authentic prototype for the future of filmmaking, nor was it a technological marvel audiences clamored to see.

So how did Imagineers expect this nearly-40-year-old technology to be a star in Discoveryland? Simple: the technology would at last take a back seat. For the first time in history, Disney would use Circle-Vision technology not as a showcase of filmmaking or a travelogue, but to tell a story… Read on…

i miss timekeeper it was awesome