Le Visionarium (Disneyland Paris, 1992)

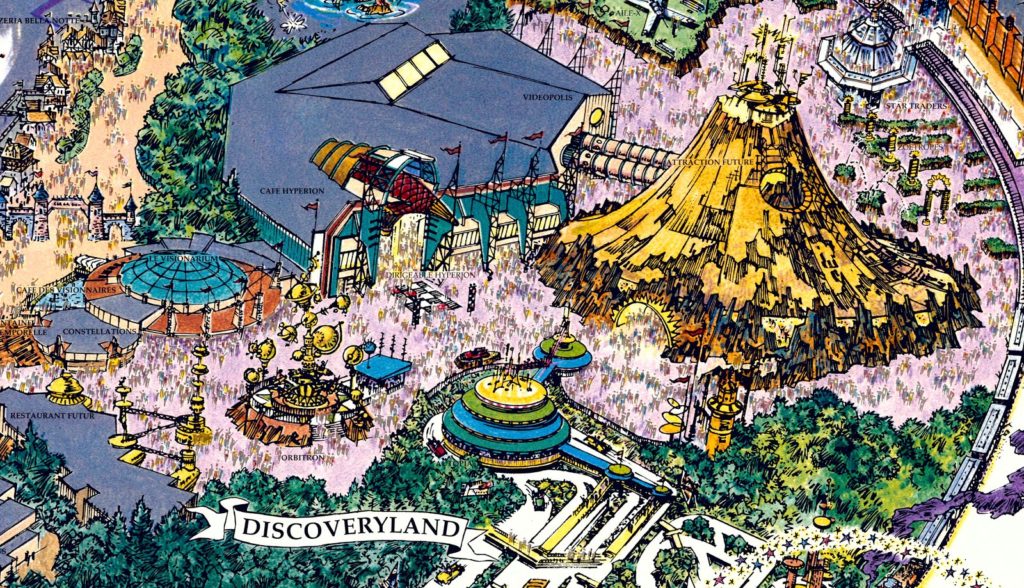

When Discoveryland opened alongside Disneyland Paris on April 12, 1992, the new kind of “land of the future” represented one of the most significant reinventions in a park that was committed to doing things differently. An apparent answer to the French public and media’s resistance and even outright hatred of the Disneyland Paris concept, Discoveryland had set out to show that Disney would carefully and culturally adapt the inherent Americana of Disneyland to fit a European spirit.

Masterminded by Imagineer Tim Delaney (and certainly influenced by the never-built Possibilityland: Discovery Bay that Disneyland Paris’ lead designer Tony Baxter had envisioned for California’s Disneyland two decades earlier), this new land would be a revolutionary change in what Disney’s dedication to tomorrow could look like.

With its determination to remaining timeless, this literary version of the land swapped out tried-and-true stateside standards and styles for rich, retro-futuristic scenes bordering on steampunk: a gold and brass port influenced by Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. (Though present in concept art, the Lost Legend: Space Mountain – De la Terre a la Lune wouldn’t come online for three years, opening in 1995.)

But even among the extravagent and ambitious projects to be born alongside Discoveryland, perhaps Le Visionarium is among the most uniquely European.

Yes, the golden Visionarium is simply yet another installation of Disney’s nine-screen Circle-Vision 360 theater. But here in Paris, the concept was entirely reborn. While it’s still that same 1950s technology that makes up Le Visionarium’s substance, its style is all new…

Think about it: the technology behind Circle-Vision 360 was no longer an attraction unto itself, drawing guests eager to see the “future” of filmmaking. So instead, the technology would recede into the background, becoming merely a storytelling tool. The attraction inside Le Visionarium – Un Voyage à Travers le Temps – takes the concept from mere demonstration to application, as Disney’s first outright attempt to use the Circle-Vision structure to tell a story.

Which is why guests stepping into Le Visionarium weren’t simply queuing for a Circle-Vision film to marvel at the unusual and futuristic filming technique, or to see how well the encircling screens lent themselves to travel displays and capturing natural wonders. Instead, they’d come to see a Time Machine.

In fact, guests would begin their journey through time by stepping into a retro-futuristic bronze and velvet library criss-crossed by brass steam pipes, stocked with dozens of models representing transportation through the ages…

A perfect match for Discoveryland’s setting and story, the steampunk-stylized lab featured suspended models of vehicles designed to explore the air (Da Vinci’s fabled Flying Machine, zephyrs, the Albatross from The Clipper of the Clouds…), of the sea (Nemo’s Nautilus, steamships, and more), and more…

This Victorian laboratory of contraptions is merely the workshop of our host, The Timekeeper, who’s invented a new kind of transportation device… one that can propel through time. In this case, the test subject would be Timekeeper’s assistant, Nine-Eye, a nine-eyed self-propelled robot who catches us up on the inventor’s idea: to depart for the past to meet great minds who’ve shaped the future we now inhabit.

As a montage of Nine-Eye’s “training runs” show (think, plunging over Niagara Falls, riding a centrifuge, and hitching a ride on a space shuttle), Timekeeper and his assistant might not have every quirk worked out yet. But regardless, it’s time to travel… As the doors to the theater open, guests proceed into a cavernous circular room with standing room only, and rails to lean on for comfort…

Un Voyage à Travers le Temps

Once inside the main Circle-Vision theater, guests would find the loveable and frantic Timekeeper at the controls. The eclectic Audio-Animatronic would welcome guests to a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to meet the great minds of the past! Today, we can bear witness to the first successful deployment of Nine-Eye – his robotic assistant (voiced by French actress Myriam Boyer) – through time itself!

As luck would have it, Nine-Eye’s… well… nine eyes… are all cameras that will be able to capture her journey through time, sending back a life video feed that will be projected around us in the Visionarium! What could go wrong!?

The two Audio-Animatronics are surprisingly compelling for the early ’90s – Timekeeper a humanoid with impressive articulation, and Nine-Eye with a truly surprising “flying” effect. You can see both figures’ patent illustrations in the Passholder-exclusive image gallery above.

In a flash, Nine-Eye is off! … Accidentally landing in the prehistoric Jurassic Age, with a viscious Allosaurus on the prowl. With the flip of a switch, the Timekeeper propels her forward as the theater is overcome in a time vortex, racing ahead to… the Ice Age, over 12,000 years ago. Turns out, the Time Machine doesn’t do well with precision…

After a few insiginificant stopovers (like interrupting da Vinci’s painting of the Mona Lisa and maybe-accidentally inspiring a few sketches in his legendary sketchbook, swinging by Mozart’s 1763 concert for King Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour, and fast-forwarding through the construction of the Eiffel Tower in 1899), Nine-Eye finally hits her mark: the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris – the World’s Fair for which the Eiffel Tower icon was initially comissioned.

There, Nine-Eye listens in on a (fictional) conversation between the (non-fictional) H.G. Wells (played by noted Shakespearean actor and Academy Award-winner Jeremy Irons – best known to Disney fans as the iconic voice of Scar in The Lion King) and Jules Verne (played by legendary French actor Michel Piccoli). The two major literary figures (and inventors of science fiction) debate the possibility of time travel, with Verne dismissing Wells’ 1895 novel as “impossible.” As Wells leaves, dejected, Verne noticed Nine-Eye, reaching out to grab her just as Timekeeper throws the switch to bring her home.

What follows is a dash through time as Verne desires to see more of the future he so lovingly imagined in his stories. You can see the French-language, Disneyland Paris of the attraction here:

But of course, the story of the Timekeeper is far from over… While Discoveryland seemed to have solved the “Tomorrowland Problem” once and for all, Disney still has those “outdated” mid-century tomorrows in California and Florida to deal with…

Discoveryland USA

Disneyland Paris opened in April 1992.

If you visited Walt Disney World that year, you would have had the chance to visit the Walt Disney Story – a long-running exhibition on Magic Kingdom’s Main Street, U.S.A. Beginning in 1981, the Walt Disney Story had been used on and off as a preview center displaying models of upcoming theme parks and attractions. And just as Disneyland Paris readied for opening, the model on display in the future projects section of the exhibit was… Discoveryland USA.

In fact, this land-wide overlay to freshen up Magic Kingdom’s Tomorrowland wouldn’t necessarily be a direct import of Paris’ Discoveryland; Florida’s “Discoveryland USA” wouldn’t be awash in bronze and copper, folding in the literary works of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Rather, it would take the tenets of Discoveryland – its timelessness, original stories, and science-free, retro-futurism – to do something equally as evergreen, but very different.

Whereas Disneyland Paris’ Discoveryland was a fantasy future, Magic Kingdom’s would be a sci-fi future – envisioned as a historically-rooted city as it would’ve been seen in pulp comic books and sci-fi features of the 20th century.

Some of this built-out rebuild of Tomorrowland survived – mostly by way of the land’s eastern half and entryway. Though it was meant to debut within the Possibilityland: Tomorrowland 2055 at Disneyland, major budget cuts post-Paris had cancelled California’s Tomorrowland renovation entirely, sending the Lost Legend: Alien Encounter to Florida instead as the land’s anchor.

Other concepts were left on the cutting room floor – chiefly, the western half, which would’ve replaced the Modern Marvel: Carousel of Progress with a “Flying Saucers” attraction, and a “Future Project” said to be an OMNIMAX dome simulator (perhaps the rudimentary technology once planned for a never-built Epcot Space pavilion).

Meanhile, the Tomorrowland Terrace restaurant would’ve been transformed into the announced-but-never-executed Astronomers Club – a stellar equivalent of the Lost Legend: The Adventurers Club, allowing diners to mingle with Galileo, Jules Verne, and Leonardo da Vinci in a metallic observatory (see the rare, Passholder-exclusive concept art, above).

And what would’ve brought those scientific thinkers from their respective centuries to a shared astronomers’ headquarters in a sci-fi city of yesteryear?

Across the entryway in the “south” showbuilding, the old Circle-Vision 360 theater would come to life once more as The Transportarium, showing a time-traveling journey called From Time to Time… Read on…

i miss timekeeper it was awesome