EPCOT’s Issues

Disney insiders have it on good authority that even by the mid ‘90s, interest in EPCOT Center was waning. It wasn’t just that the new Disney-MGM Studios had cannibalized some of EPCOT’s attendence; even the park’s most ardent supporters can easily see why. We’ll boil it down to three big picture reasons:

1. STYLE: A dated look and feel.

Think about it: the 1960s and ‘70s had been an era with a very particular motif when it came to futurism. Look no further than the beloved Tomorrowlands designed in those decades: lands of sleek, Googie architecture, simple white geometric patterns, and the “ease and simplicity” of the Space Age. In fact, fans beg Disney to return Tomorrowland to that now-nostalgic architectural style that’s re-entered pop culture as a naïve-but-natural view of the future.

The look of Epcot’s Future World? Not so much. Firmly rooted in the late ‘70s, the look and feel of Future World is defined by large concrete plazas, harsh brutalist architecture, and an altogether cool gray and beige color palate. So while that long-lost look of the ‘60s and ‘70s Space Age has come back around to be retro-cool, the massive pavilions of Future World haven’t and – maybe – never will…

Disney’s answer in the ’90s? To mask the cool, pastel, gray ’80s pavilions by applying layers of saturated, vibrant, neon paint (see above) that, in turn, just looked odd on ’80s architecture and dated the pavilions to the ’90s – still no better for audiences of the new millennium!

2. SUBSTANCE: Industry over imagination

On the simplest level, EPCOT Center had gained a reputation as a pop culture punch line; it was the Disney park that many kids detested spending a day at. What child, after all, would choose to forego a day with Magic Kingdom’s princess or pirates or a day at the new Disney-MGM Studios alongside Ninja Turtles, explosions, Star Wars, and mermaids for a day of educational dark rides through the histories of industries? Expensive international cuisine? Zero Disney characters?

3. SPONSORS: Funding the future.

In each Lost Legend entry for EPCOT Center classics, the story generally pivots around sponsorship. Disney’s once-brilliant move to have mega-corporations pay for pavilions and commit to their upkeep started to turn around in the mid-‘90s. By then, contracts were beginning to expire, and rather than recommitting and doubling down on investment as Disney had hoped, many EPCOT Center sponsors were choosing to leave, more or less sticking Disney with enormous, unfunded pavilions to suddenly infuse with cash (and, if that particular pavilion was lucky, some creativity, too).

It had to have been clear to Disney that EPCOT Center needed to change. So it did. EPCOT Center was renamed Epcot ’94, then Epcot ’95 before switching to the simpler Epcot we know today. But on a wider scale, Disney had big plans…

Project: GEMINI

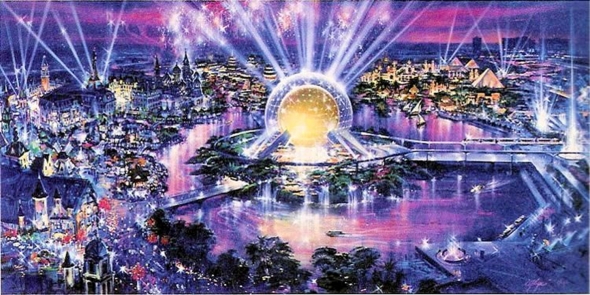

As luck would have it, Disney was working with a pretty full portfolio of Epcot ideas. That’s because, in the early ‘90s, Disney had announced a second gate coming soon to the original Disneyland back in California. The never-built Possibilityland: Westcot (above) was a new take on the Epcot concept that would’ve fixed the three issues – style, substance, and sponsorship – that had already become apparent in Epcot in the decade since its opening.

Though Westcot was cancelled (replaced by the Declassified Disaster: Disney’s California Adventure), the important work designers had done on it would now translate back to Epcot as part of a massive overhaul supposedly referred to as Project: GEMINI.

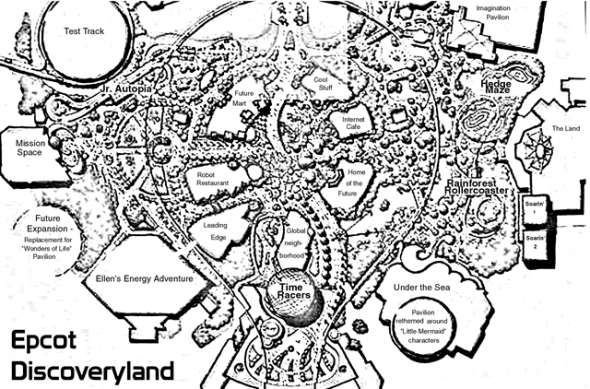

According to entertainment writer Jim Hill, this floor-to-ceiling facelift would redefine Epcot for the 21st century. First of all, those cold, concrete expanses and wide, sun-bleached plazas would be broken up and reformed into Discoveryland, an overflowing oasis of the future marked by forested paths, waterways, organic rockwork, multi-leveled gardens, and waterfalls, all reigned over by the park’s icon, now re-clad in golden tiles. This was the more forward-thinking answer to Future World developed for Westcot, and now it would serve to prepare Epcot for a new century… Style? Check.

As for substance, Project: GEMINI would’ve turned Epcot into Disney’s “discovery park,” inviting exploration into areas of science and industry with cutting edge, technological, reality-rooted thrill rides rather than the educational dark rides of old. Some of the piecemeal parts of Project: GEMINI did come to pass, like Horizons becoming Mission: SPACE, World of Motion becoming the original TEST TRACK, and the arrival of the old Californian Soarin’ in the Land pavilion – and you can see how each turned Epcot’s thesis on its head with a very distinct intention of transforming the park’s reputation and offerings.

But equal interest is what did not come to be: the transformation of Spaceship Earth into a high-speed roller coaster / dark ride through time called Time Racers; the dissolution of Innoventions parenthetical buildings in favor of smaller, forested showbuildings; the addition of a roller coaster through the canopy of the rainforest out front of the Land… and finally, the first characters to break into Epcot’s once-hallowed ground, swimming into The Living Seas… Nope, not Nemo.

The Living Seas was set to become Under the Sea, featuring characters from the movie that had kicked off Disney’s Renaissance: 1989’s The Little Mermaid. What’s especially ironic is that this planned character overlay would’ve essentially retrofitted The Living Seas with the more fantasy-infused storytelling that had been planned as far back as the ’70s…! You can easily imagine the underwater world of Triton taking the place of Poseidon, with Atlantica overlaid atop the pavilion’s otherworldly oceanic scenes.

Obviously, while pieces of Project: GEMINI came to pass (including Epcot’s retitling as a “discovery” park), they weren’t intentionally bundled with the change in style that would’ve made them more than the sum of their parts. The Living Seas outlived the concept of a Little Mermaid overlay, surviving into the New Millennium with its distinctly-scientific style and setting even as Future World’s other pavilions evolved and morphed. Would the Living Seas last where other Epcot pavilions hadn’t? Of course not. Disney was just waiting for the right intellectual property to come along….

Finding Nemo

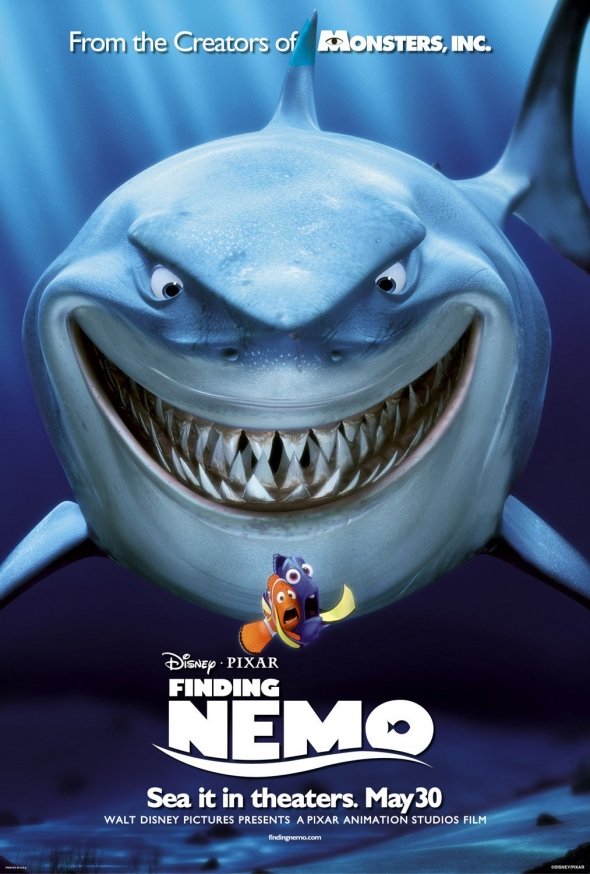

Throughout the ‘90s, Disney’s relationship with young computer animation studio Pixar was rising. Disney’s agreement to distribute Pixar’s first three films (Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, and Monsters Inc.) had proven to be a wise one, as each ran away with $300 million at the box office, out-earning even some of Disney’s “Renaissance” films in the era. Wiser still was Pixar’s part of the deal, requiring that any time Disney’s name appeared, their own did as well, and in an equally-sized logo… We explored that (and the rise of Pixar in Disney Parks) in a must-read special feature: Disney•Pixarland.

So even as Michael Eisner’s relationship with Pixar’s Steve Jobs began to buckle, the two companies signed yet another three picture deal… but this time, Jobs was ready. He argued that not only did Pixar deserve a bigger cut of the profits, but that Pixar should retain ownership of their first three films. Eisner was incensed.

A fourth Disney•Pixar release was mere months away – Finding Nemo – and Eisner began internally suggesting that the film wasn’t going to be a hit. He hadn’t liked early cuts he’d seen of the movie and believed it was bound to be Pixar’s first failure. According to the LA Times, Eisner began to suggest it wouldn’t be such a bad thing to have Nemo fail; that it would give Steve Jobs “a reality check.”

…But 2003’s Finding Nemo earned $940 million at the box office, becoming the highest grossing animated film ever. And designers knew just where to bring it to the parks…